In 1828, a mummified body was put on display in the entrance hall of the Museum of the Manchester Natural History Society.

An obsession with mummies and all things Egyptian had been raging through Britain for some time, but this particular exhibit hadn’t been plundered from a pyramid or snatched from a colony. The mummy was the body of one Hannah Beswick, a wealthy Manchester woman who’d died seventy years earlier.

Hannah’s remains – displayed in a glass case between mummies from Egypt and Peru – proved popular with the paying public. In fact, she was the museum’s star exhibit. But how did a lady from a respectable Manchester family end up as the attraction that became known as the Manchester Mummy?

The following tale includes duplicitous doctors, fears of being buried alive, ‘corpses’ rising up out of coffins, glimpses of Hannah’s ghost, macabre collections of ‘curiosities’, rumours of hidden treasure, and a society negotiating shifting perceptions of life, death, science, entertainment and medicine.

Let’s see if we can unwrap the peculiar case of the Manchester Mummy.

The Origins of the Manchester Mummy: A Resurrected Relative and a Fear of Being Buried Alive

In 1688, Hannah was born to John and Patience Beswick of Cheetwood Old Hall, Manchester. She inherited substantial wealth when her father died in 1706. Hannah moved to a manor house called Birchin Bower, in Hollinwood, near Oldham, where she led an unremarkable and comfortable life. This agreeable existence, however, was disturbed by the ‘death’ of her brother John.

Just before the funeral, as the mourners were about to close the coffin, somebody saw John’s eyelids flicker. The family physician Dr Charles White stepped up, examined the body and declared to John’s astounded friends and relatives that he wasn’t actually dead. The funeral was abandoned, John recovered consciousness a few days later and lived for many more years.

A terror of being buried alive was widespread in Georgian and Victorian times.

This incident must have been shocking for Hannah and all those present, but such cases weren’t as unusual as we might think. The medical understanding of phenomena such as comas and resuscitation techniques was primitive compared to today. There were well-publicised cases of people waking up in mortuaries, at their funerals or on the dissection or embalming table. Evidence also sometimes emerged of those who hadn’t been so lucky and who’d suffered a dreadful death after being entombed or buried alive.

It seems Hannah developed a deep fear of such a fate befalling her. As well as the dramatic incident with John, it’s likely she was affected by the widespread terror of premature interment that haunted the Georgian (1714-1837) and Victorian (1837-1901) epochs. Horrific stories circulated, and lurid books and newspaper articles were published, giving details of those who’d been found – their fingers bloodied, their shrouds torn – who’d died while trying to escape their coffins and tombs.

When Hannah wrote her will – dated 25th July 1757, less than a year before she died – she was still under the shadow of such fears. She demanded her body be kept above ground and regularly examined for signs of life until it was certain she was dead.

A Disputed Will, a Possibly Dishonest Doctor and the Making of the Manchester Mummy

Dr Charles White, the creator of the Manchester Mummy

There seems to be some confusion over the terms of Hannah Beswick’s will. It’s rumoured she left £25,000 (equivalent to about three million pounds today) to Dr Charles White provided he delay her burial until he was sure she was dead. But her will actually states that White should get only £100 and that £400 should be spent on funeral expenses. It’s been suggested that Hannah might have permitted White to keep any of the £400 left over. Some think he may also have been in debt to Beswick and would therefore have been expected to repay what he owed following the funeral. So it could have been in White’s interest to find a way to make sure no funeral took place. Hannah’s will, however, lists Mary Graeme and Esther Robinson as executors rather than White. Hannah Beswick’s will was still being disputed over a century after her death.

What we do know is that White embalmed Hannah’s body. This was despite the fact her will didn’t request embalming and stated that burial should only be postponed until there was no doubt she was dead. As well as the financial motives mentioned above, White may not have been able to resist possessing a mummified human. Like many scientifically inclined gentlemen of his period, White had a ‘collection of curiosities’ – a sinister hoard that boasted both ‘wet and dry’ specimens, among them the skeleton of Thomas Higgins, an infamous highwayman who’d been hanged. White – a founder of the Manchester Royal Infirmary and a pioneer of obstetrics – seems to have been obsessed with anatomy.

The exact method White used to create the Manchester Mummy isn’t known. White, however, had been a student of the anatomist Dr William Hunter, who’d developed the technique of ‘arterial embalming’. This involved filling the body’s veins and arteries with a mixture of turpentine, vermilion and oil of lavender and rosemary. Also, under this method, the organs were removed and shrunk in water, blood and fluids were squeezed from the corpse, and the body was washed with alcohol. The organs were then put back and the body’s cavities filled with plaster of paris. Finally, the body was sewn up, the openings were stuffed with camphor and the corpse was coated with tar. It’s likely White used such a procedure to transform Hannah Beswick into the Manchester Mummy.

The Manchester Mummy Is Displayed and Hannah Acquires a Fame She Never Found in Life

Hannah’s mummy was first kept at Ancoats Hall, the house of a member of her family. Soon, however, she was moved to White’s home in nearby Sale, where she was kept in the case of a grandfather clock. News of the Manchester Mummy soon spread and visitors streamed to White’s house to view her. White entertained them by whipping back a curtain that covered where the clock’s face would have been – to reveal the embalmed face of Hannah. Celebrities, like the author Thomas de Quincy, were among those who flocked to see Hannah’s corpse. It’s not known if any of them commented on how the remains of a rich heiress propped up in a clock made a fitting piece of memento mori art.

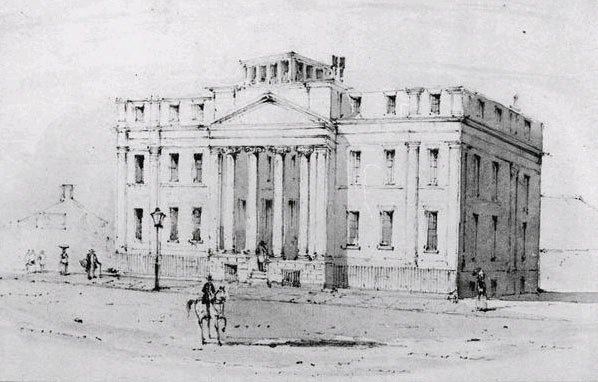

When White died in 1813, he left the Manchester Mummy to a friend and colleague, one Dr Ollier. Upon Ollier’s death in 1828, the mummy was given to the Museum of the Manchester Natural History Society. It soon became one of the museum’s most popular items and began to be widely referred to as the Manchester Mummy or the Mummy of Birchin Bower. Hannah was exhibited in the entrance hall between considerably more ancient mummies from Egypt and Peru. Her relatives were allowed to visit her for free.

The Museum of the Manchester Natural History Society, where the Manchester Mummy was displayed.

No photos or sketches of the Manchester Mummy have survived, but the local historian Phillip Wentworth described Hannah thus: ‘The body was well-preserved, but the face was shrivelled and black. The legs and trunk were tightly bound in a strong cloth … and the body, which was that of a little old woman, was in a glass coffin-shaped case.’

A visitor in 1844 observed that Hannah was ‘one of the most remarkable exhibits in the museum’. According to the writer Edith Sitwell, the ‘cold dark shadow of her mummy hung over Manchester.’

In 1867, the museum – which was experiencing financial difficulties – was bought by Owens College, a forerunner of the University of Manchester. Around the time of this sale, it was decided that Hannah was ‘irrevocably and unmistakably dead’. With all doubts concerning her mortality resolved, it was felt the terms of her will should be respected and she should be given burial. It’s also worth pointing out that the public’s fascination with the Manchester Mummy was finally starting to wane.

The Manchester Mummy Is Laid to Rest

Burying the Manchester Mummy wouldn’t be a simple matter. Since 1837, UK law has stated that burials cannot take place unless a doctor has issued a death certificate. As Hannah had been dead for over a century, no such certificate could be drawn up. An appeal had to be submitted to the Secretary of State, who then ordered her burial.

With permission also granted from the Bishop of Manchester, Hannah Beswick could finally be laid to rest. On 22nd July 1868, Hannah was buried in Harpurhey Cemetery, over 110 years after she had died. The Manchester Mummy was interred in an unmarked plot as there were fears such a famous corpse might be a target for graverobbers.

Rumours of Hidden Treasure and Reports of Hannah Beswick’s Ghost

In 1745, the Scottish rebel Bonnie Prince Charlie arrived in Manchester with his army. It’s said this caused Beswick concern over her money, prompting her to bury some of her fortune. Hannah, however, died without telling her relatives where she’d hidden the loot.

After Hannah’s death, Birchin Bower was converted into workers’ tenements. Some residents reported seeing a phantom figure in a black gown and white cap and the belief grew up this was the ghost of Hannah Beswick. This spectre would, apparently, float across a parlour then disappear when it reached a certain flagstone. Some claim a man living there levered that flagstone up, found a stash of gold and sold it to the Manchester dealer Oliphant’s, getting £3 10s (equivalent to around £450 in 2020) for each gold piece.

Hannah Beswick’s former home of Birchin Bower was reputedly haunted by her ghost.

The tenements were later knocked down and a factory for the electrical company Ferranti was built on the site. Glimpses of the black-gowned spook, however, continued. Perhaps the ghost is Hannah’s, angry at the way her remains have been treated.

A bizarre coda to the Manchester Mummy case came in 1890 when Cheetwood Old Hall was being demolished. A double coffin was unearthed beneath the drawing room. The mystery of this coffin has never been explained, but many suspected this grim discovery was linked to the Beswicks and Dr Charles White. The good doctor had lived for a time at the Hall after Hannah had moved out to Oldham.

What Does the Peculiar Case of the Manchester Mummy Tell Us?

The story of the Manchester Mummy is certainly a strange saga, but what does it tell us about the dark anxieties and obsessions from which such an artefact emerged? What does this sinister tale reveal about the epoch in which the Manchester Mummy was created, displayed and eventually laid to rest? Read on to learn of Georgian and Victorian terrors of being entombed alive and how Victorian respectability finally did battle with the freakish and macabre.

Hannah Beswick’s Phobia Was Just One Instance of a Widespread Fear of Being Buried Alive

Though people have always feared premature burial, the terror of such a fate became far more common in Georgian and Victorian times. This was largely due to advances in medical knowledge. By the 1740s, evidence was accumulating that people who seemed dead could sometimes be revived by mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Doctors also started experimenting, occasionally successfully, with reviving patients using electrostatic machines. In 1774, a London doctor used a portable electrostatic generator to resurrect a ‘dead’ child who’d fallen from a window.

Medics were also realising that the symptoms indicating death could be deceptive. The new disease of cholera sometimes made it hard to feel a pulse and some doctors even suggested the symptoms of scurvy could be mistaken for putrefaction. As the public became aware that the boundaries between life and death were fuzzier than they had imagined, it caused great concern. If you could appear dead but were in fact revivable, surely this meant there was a significant danger of being buried alive.

Books and articles gave horrifying accounts of those who’d been buried too early. In 1885, the New York Times reported that a North Carolina man had been found turned over in his coffin with much of his hair pulled out and scratch marks on the casket’s insides. In 1886, when the coffin of a Canadian girl was opened, she was found with her knees tucked up under her body and her shroud ripped to pieces. In 1883, a Boston doctor published a book entitled One Thousand Persons Buried Alive by their Best Friends.

Due to a fear of being buried alive, a Vermont man insisted his tomb be fitted with a window. (Photo: Historic Mysteries)

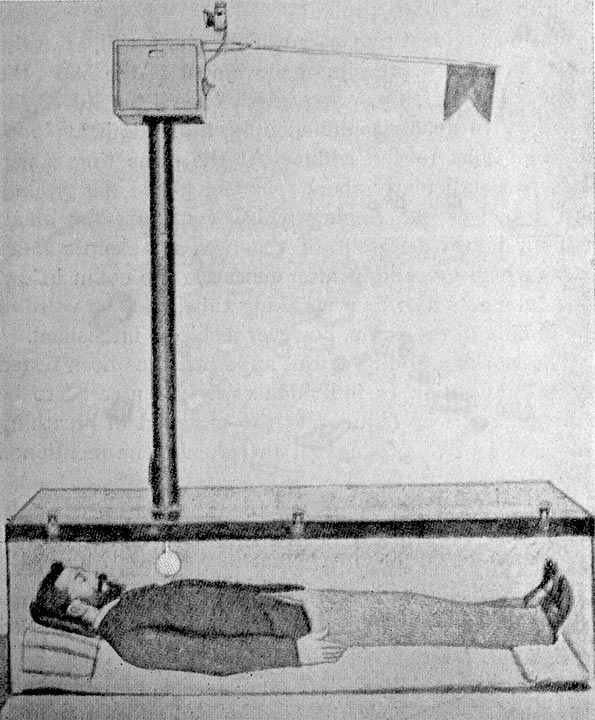

The terrors of premature interment resulted in some ingenious designs for coffins and tombs. Robert Robinson, from Manchester, who died in 1791, insisted his coffin should be fitted with a glass plate and his mausoleum with a door. A cemetery watchman was to check the glass to see if Robinson’s breath had misted it. Timothy Clarke Smith, who died in Vermont in 1893, stipulated his tomb should contain a window positioned six feet above his face so his friends could periodically check on him. Designs for ‘safety coffins’ were patented, equipped with air pipes or elaborate systems of flags and bells to attract attention. One casket even came fitted with a ladder to allow those mistakenly presumed departed to ‘ascend from the grave’.

A common fear of being buried alive led to a range of ‘safety coffins’ being patented.

Others, like Hannah Beswick, insisted in their wills that burial should be delayed until there was no doubt they were deceased. Creative ways of ascertaining a person’s demise ranged from making surgical incisions and touching the corpse with red-hot irons to applying scalding liquids and even blowing smoke into the rectum!

There were perhaps good reasons why Hannah’s dread of premature burial was shared by many in her epoch. In 1895, the physician J.C. Ouseley estimated that 2,700 people might be buried prematurely in England and Wales each year. In 1896, one of the founders of the London Association for the Prevention of Premature Burial stated he’d uncovered 219 incidences of narrowly escaped premature burial, 149 cases of actual premature burial, 10 cases of bodies being dissected before death and two instances of embalming being attempted on people still alive.

Such estimates may have been exaggerations. According to the folklorist Paul Barber, the normal effects of decomposition can make it seem like corpses have been twisting around in their coffins. But the problem at the time was that while medicine was advanced enough to recognise that the signs of death could be misleading, it was still too basic to have found reliable ways of dealing with this issue. Though some physicians advocated electric shocks and mouth-to-mouth resuscitation as means of revival, such techniques would not achieve full medical respectability until the mid-1900s.

Hannah Beswick’s fears were an early example of the terrors that gripped the Georgian and Victorian worlds. Such anxieties can be seen in the literature of the era. Edgar Allan Poe’s stories The Premature Burial, The Cask of Amontillado and The Fall of the House of Usher all deal with the horror of being interred too soon. Frankenstein, published in 1818, examines the murky frontiers that divide the dead from the living while darkly exploring the possibilities of reanimation. A fascination with the ambiguous spaces between life and death can also be discerned in the growing popularity of the vampire genre.

Respectable Victorian Society Begins to Separate the Educational, the Medical, the Entertaining and the Freakish

Hannah Beswick’s transformation into the Manchester Mummy came in an age in which the boundaries between science and curiosity, education and amusement were much looser than today. Collectors hoarded items that could advance scientific and medical knowledge alongside objects that were merely status symbols or sources of entertainment for their friends. Some artefacts – such as the Manchester Mummy – could fulfil all these purposes.

Dr White probably enhanced his anatomical expertise thanks to his mummification of Hannah, but he also enjoyed the showmanship of tugging his curtain back to reveal Hannah’s face to his astonished guests. He no doubt also appreciated the celebrity the Manchester Mummy gave him. White’s mentor Dr Hunter possessed an eclectic collection of around 10,000 artefacts, ranging from books, coins and shells to geological and medical specimens to items that were utterly macabre. Hunter’s collection, for instance, included the skeleton of the famous ‘Irish Giant’, the seven-foot seven-inch tall Charles Byrne.

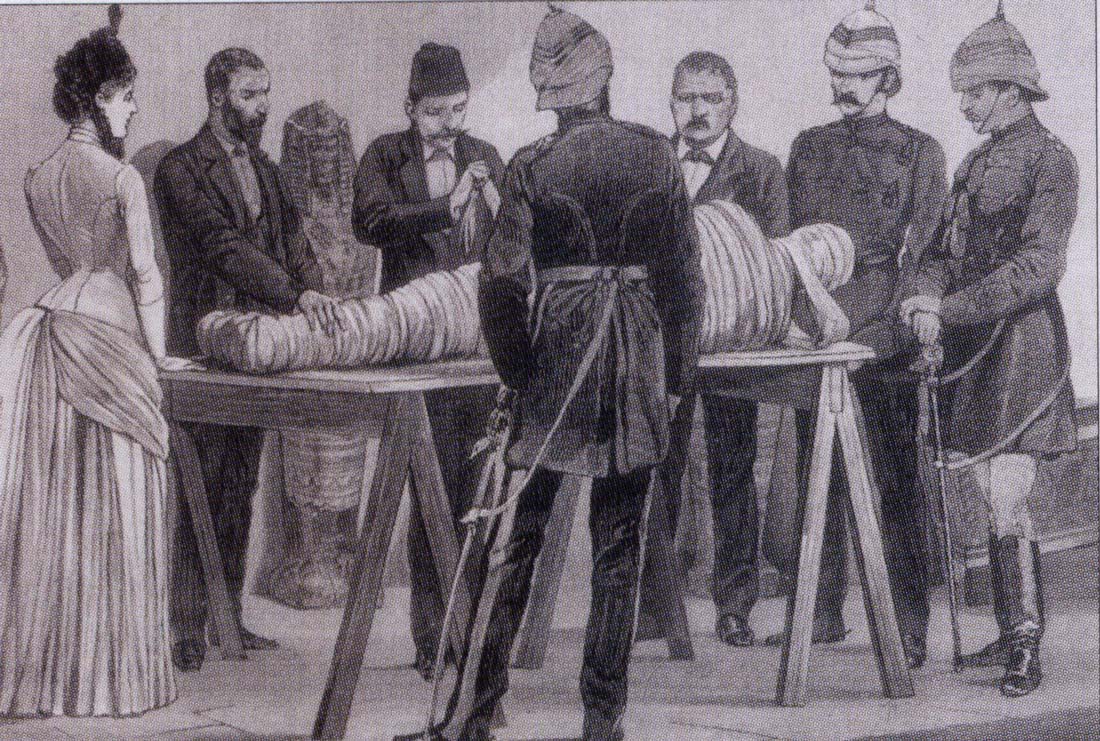

Such an approach was also common in the museums of the period. With their disorganised and frequently bizarre collections, museums were viewed not just as places of education, but as centres for satisfying one’s curiosity and even morbid voyeurism. And the epoch did have a fascination with human remains. As well as Hannah’s corpse, the Museum of the Manchester Natural History Society boasted a bitumen-covered Peruvian mummy, a preserved Maori head and an Egyptian mummy called Asroni, who still resides in Manchester Museum today. Indeed, a popular pastime in the era was watching the unwrapping and dissection of Egyptian mummies (some genuine, some fake). These events, despite having an educational veneer, were primarily spectacles. Some unwrappings were organised as high society parties, with fancy invitations sent to guests; others were ticketed public events, which often sold out.

In such a ghoulishly curious epoch, in which enthusiasm for new knowledge and science mingled with the desire to be entertained, it’s not a surprise that the Manchester Mummy was a popular attraction.

A Victorian mummy unwrapping session

This attitude, however, began to change as the Victorian age progressed. At the same time as scientific knowledge was expanding, an educational and moral earnestness started to grip Britain. Museums were becoming more professional and their displays better organised into distinct categories. Macabre exhibits like the Manchester Mummy – which had little obvious educational value and didn’t fit into any scientific classification – began to fall foul of both moral and academic outlooks.

These strengthening ideals of educational virtue and civic culture can be seen in the fact that – a few years after the Manchester Mummy’s burial – Owens College moved from its city-centre, crime-plagued location on the insalubrious Quay Street. Here, according to one critic, ‘the entrance from Deansgate was guarded by a very Scylla and Charybdis of disreputable public houses’. The college fled to Oxford Road on what were then the more wholesome outskirts of the city. A grand Victorian Gothic building – designed by Alfred Waterhouse, also responsible for London’s Natural History Museum and Manchester’s splendid town hall – was built to house both the college and the revamped Manchester Museum. (As the Museum of the Manchester Natural History Society was now known.)

All this could be seen as a seizing of control of culture, leisure and learning by a rising, confident and respectable middle class. The Manchester Mummy – with its ghoulish aura of the freakshow – didn’t fit into this new world and so Hannah was decently buried.

Manchester Museum is housed in a Victorian Gothic building designed by the famous architect Alfred Waterhouse.

In both life and death, Hannah Beswick made a strange, centuries-spanning journey. This journey took her from being an individual person to a source of wealth and bequests to a scientific experiment to a macabre curiosity to an embarrassing inconvenience to a person deserving of basic respect once more. Thus, to the sound of the shovelled earth of Harpurhey Cemetery, the Manchester Mummy’s bizarre odyssey came to its end.

But perhaps mythological and ancient archetypes – such as mummies – will always have the ability to break free from the past and intrude into more modern cultures, especially cultures undergoing intense anxiety or change. Similar folkloric characters that have invaded later eras include Glasgow’s Gorbals Vampire, the Cardiff Giant, the Highgate Vampire and London’s Spring-Heeled Jack. Both modern innovations and modern fears can encourage such interlopers. With the Manchester Mummy, we can see how the archaic and up-to-date, the gruesome and clinical, the superstitious and scientific were all wrapped up in one sinister figure.

Me and my dad was talking about hannah beswick, I decided to google to see what come up. My nana used to live in hollinwood, me and my dad was talking about old ghost stories and one was her. My nana and other members of the family spoke about and seeing ghostly sighting with the description of her wearing black and she wore a bonet. when I was younger I did a project on her “the hannah beswick the mummy in a grandfather clock”, my nana also managed to give me photocopies of a map showing the land she owned. The story goes that she still searches for her gold which was hidden from the jacobites, coincedently at my primary school i also found a book, the title on the lines of ;” true ghost stories” and who was in it…yep hannah beswick

Thanks for that comment, Liv. It seems Hannah Beswick is quite a famous ghost in and around the Manchester area!

Hi David,

Very interesting. I must declare an interest in that CW is my direct ancestor and I have lived with one of the two oil paintings of him above my desk all my adult life!

He trained in Edinburgh as well as with his father Thomas and his daughter Anne married Richard Clayton of Adlington Hall in Lancs. CW lived much of his life at 1 Kings Street and he was part of an affluent family. He amongst others founded the Manchester Infirmary, St Marys Hospital and the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society and was a contributor to the Portico Library although by the time it opened he was blind.

His work in Obstetrics altered the lives of thousands of women in Manchester …the city having among the lowest death rate from Puerpural Fever in Europe. He was also responsible for numerous operative firsts.

So to put in context he is a man Manchester should be far more proud of …and him benefitting in large sums of money from this is I think very unlikely. His work is still influential to this day …. http://www.bristolmedchi.co.uk/content/upload/1/wemj/wemj-113-no-3/charles-white.pdf