One of the best-known aspects of the British, American and – increasingly – global Christmas is the figure of Father Christmas or Santa Claus. Millions of children love to believe in the tubby red-suited old man who – with his magical reindeer and uncanny ability to bend time and space so he can get round the world in just one night – joyously delivers smart phones and video games hammered together by his elves (presumably under the trademarks of Apple and Sony) in his workshop at the North Pole.

But how did this figure evolve in our folklore and culture? Were Saint Nicholas, Santa Claus and Father Christmas always the same person, and what on earth does Coca-Cola have to do with it all?

In this post, I’m going to try to clear away the piles of wrapping paper and consumerist clutter, to get the tinny toy-store carols out of my ears and to attempt to get to the bottom of this cultural conundrum.

Old Father Christmas Insists on Seasonal Merriment and Boisterous Good Cheer

In medieval England, Christmas was an important festival involving – at least for those who could afford it – feasting, drinking, dancing, games, card playing, carol singing and storytelling. By Tudor and Stewart times, it had become even more elaborate, with masques, pageants, plays and an ever more sumptuous Christmas dinner. But all this indulgence began to arouse the anger of more puritanical Christians.

In 1583, the Puritan Philip Stubbes complained, ‘In Christmas time, there is nothing else used but cards, dice, tables, masking, mumming, bowling and such like fooleries. We ought not … to swill and gull in more than will suffice nature nor to lavish forth more at that time than other times. The true celebration of the feast of Christmas is to meditate upon … the incarnation and birth of Jesus Christ.’

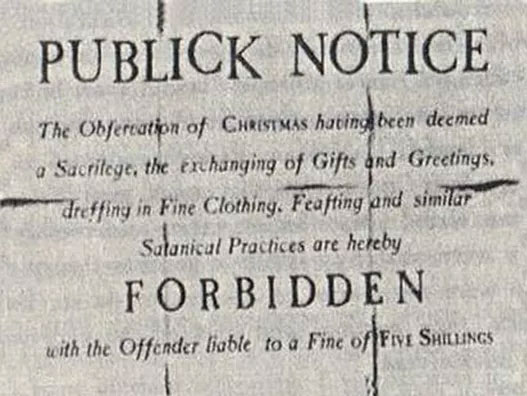

By the time the Puritans seized power during the English Civil War (1642-51), their dislike of the festival had grown stronger. Christ-mas sounded too Catholic and they were beginning to suspect the feast even had pagan origins. In 1647, a law was passed stating, ‘The said feasts of the nativity of Christ, Easter and Whitsuntide and all other festival days, be no longer observed.’ Five years later, another law said, ‘No observance shall be had of the five-and-twentieth day of December, commonly called Christmas Day.’ A law was even introduced banning plum puddings.

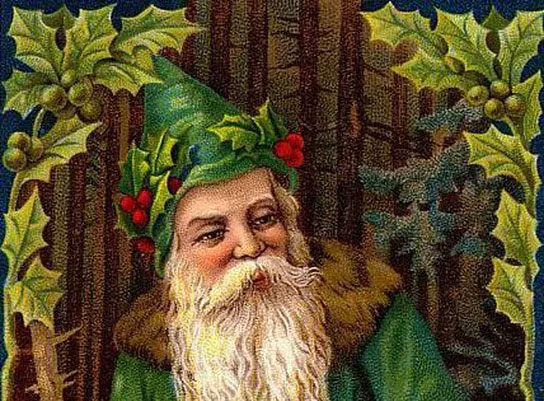

Many opposed the abolition of their midwinter holiday. People who opened their shops on Christmas Day were attacked and there were riots in several cities, with rioters insisting on hanging holly in doorways. Pamphlets protested against the ban and praised the forbidden festival. And in these pamphlets a character began to appear, a personification of feasting, drinking and merriment. Often rotund and bearded, he went by the name of Old Father Christmas. He seems to have first featured in a pamphlet in 1652, A Vindication of Christmas, which yearned for carols, roast apples and Christmas dinner.

Old Father Christmas rides a goat, still with his bowl of Christmas ale

England’s Puritan Parliament, however, kept up the ban and anti-Christmas sentiments spread to America. The Pilgrim Fathers made a point of working on Christmas Day and Christmas was outlawed in Boston in 1659. But the supporters of Old Father Christmas would not give in and their chubby figurehead became a rallying point for opposition to the Puritans and their reforms. Old Father Christmas was a symbol of the jolliness of the ‘old days’ and was deliberately contrasted to the dour Puritan outlook. His supporters continued to close their shops on the 25th, to eat roast meat and Christmas pies, and to attend secret church services.

A Puritan notice banning Christmas in Boston in 1659

When England’s monarchy was restored in 1660, London’s fountains flowed with wine and the people were given back their old games and festivities. Christmas too returned, but despite Old Father Christmas’s best efforts, the festival was never quite the same. Interest in Christmas dwindled until by Victorian times it was in danger of dying out. But, as the Victorians looked around them at their overcrowded, polluted cities and the mechanisation of life the Industrial Revolution had brought, they began to pine for an imagined past: an idealised vision of a simpler, happier England of woods, fields, clean air and joyful folkloric customs. The spirit of Old Father Christmas would soon be stirring again.

An image from 1686 shows Old Father Christmas triumphant after the festival’s return

So Where Did Santa Claus Come from?

In Victorian England, and in America around the same time, Christmas was reviving. Charles Dickens helped resurrect the festival with his massively popular book A Christmas Carol, which is full of Christmas dinners, presents, games and good cheer. But there was no concept that Christmas gifts were brought by any Santa-Claus-like figure. While Old Father Christmas had resembled Santa with his beard and corpulence, he had never had any gift-giving function. He had no reindeer or sleigh and was certainly never thought of as residing at the North Pole.

The modern Santa Claus emerged in New York. After the War of Independence (1775-83), English things were out of favour and Americans started looking for the roots of their culture in other European countries. The rich Christmas traditions of Dutch, German and Central European immigrants began to be championed. The image of the modern Santa was more or less crafted by a poem called A Visit from St Nicholas (commonly known by its first line Twas the Night Before Christmas), written by Clement Clarke Moore in 1823. Here St Nicholas arrives on a sleigh drawn by reindeer, he comes down the chimney and he has a sack of presents that he puts into stockings. He’s ‘dressed all in fur from his head to his foot’, bearded, plump and rosy-cheeked.

Saint Nicholas was a Greek Bishop who lived in Myra, now south-west Turkey, in the 4th century. He was noted for his care of children, his generosity and gift giving. According to one story, he saved the daughters of a poor family from being forced into prostitution by sneaking into their house at night and placing gold in their stockings. By the 13th century, he was well-known in the Netherlands as Sinterklaas. His feast day was on December 6th and the custom of giving gifts in his name soon spread through parts of northern, central and southern Europe.

After the Reformation, the Dutch custom was made more Protestant. Gift-giving was now the responsibility of the Christ Child and the day for exchanging presents switched to Christmas Eve. But in popular culture, it’s likely the associations between St Nicholas, presents and Christmas lingered on. These associations were brought to America by Dutch migrants. The New York Historical Society retroactively named St Nicholas as the patron saint of New York (or, as it had been called, New Amsterdam). Images of St Nicholas – in his bishop’s robes – started appearing in the States around 1810, but depictions of him soon became more secular.

The New York cartoonist Thomas Nast drew an annual image of Santa Claus for over thirty years. It’s interesting to note how Nast’s images changed over time. In 1862, Nast was depicting Santa as a small elflike creature who supported the Union in the Civil War. (In The Night before Christmas, Santa is also said to be ‘a merry old elf’ with ‘a miniature sleigh and eight tiny reindeer’). By the 1880s, Nast’s Santa had evolved into something like the large, definitely human character we know today, perhaps with input from the English figure of Father Christmas.

Santa Claus by Thomas Nast in 1881

How did St Nicholas acquire his sleigh, reindeer, elves and home at the North Pole? St Nicholas was from Asia Minor and as Sinterclaas he travelled on a white steed. The reindeer and sleigh may come from deep roots in the northern European mind. The Germanic god Thor travelled on a flying chariot pulled by magical goats, and reindeer have long been viewed by northern Europeans as mystical creatures. The anonymous New York author of the first poem to mention Santa’s reindeer, 1821’s A New Year’s Present, may have had Lapp origins. Santa’s North Pole home – the first known reference to which is in a Thomas Nast cartoon – likely came from people assuming that if Santa had reindeer he must live somewhere cold. His elves – also from European folklore – are first mentioned in literature in 1856.

Santa Claus appeared in Britain in the 1860s, when other Christmas innovations such as stockings, crackers and Christmas cards were being introduced. Santa slowly took on the features of the indigenous Father Christmas until the two figures merged into one.

So Why on Earth Is Santa Claus Connected with Coca-Cola?

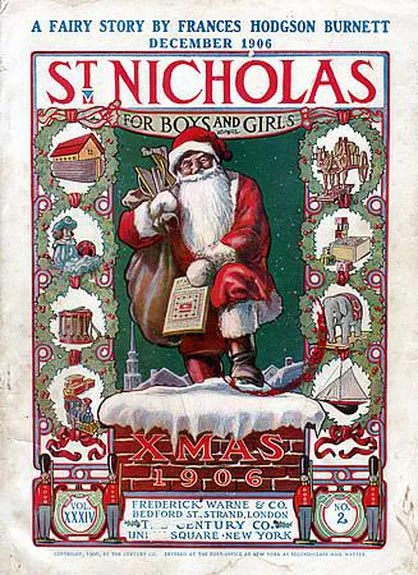

By the late 19th century, the Santa Claus/Father Christmas character had evolved into a fat, jolly, sleigh-driving present giver who came down chimneys. However, certain things about him were still not fixed. The colour of his outfit, for example, could change and there are depictions of him clothed in white, blue and green as well as red.

For some time, Santa Claus’s colours were not fixed

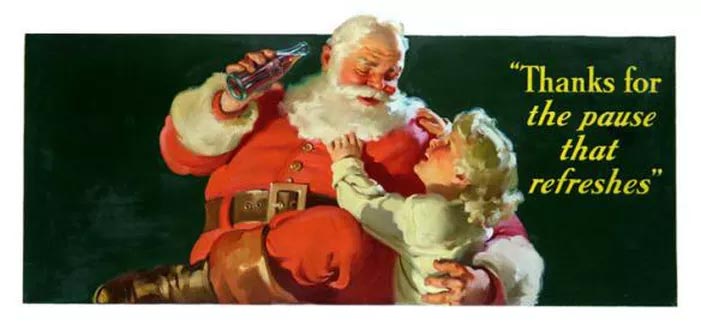

Some people think the modern Santa was the creation of a series of Coca-Cola ad campaigns that ran from the late 1920s to the 1960s. There is, however, evidence the image of Santa was becoming more defined before the Coke campaigns started. A New York Times article of 1927 stated, ‘A standardised Santa Claus appears to New York children. Height, weight, stature are almost exactly standardised, as are the red garments, the hood and the white whiskers.’ But Coke’s series of commercials certainly cemented the Santa image and popularised it around the world.

By the early 1900s, Santa was developing a preference for red

Santa, in his generosity, gave the Coca-Cola Company a boost. In the late 1920s, the company needed to re-evaluate its business plan – it had to find a way to sell its cold drinks in winter, to combat the Depression and increase its sales among children. (Prior to these campaigns, Coke was viewed as more of a medicine). Santa served all three requirements admirably. The Coca-Cola Santa was drawn by Haddon Sundblom and modelled on his portly neighbour, a retired salesman. When the neighbour passed away, Sundblom based the Santa figures on himself. It was handy that Santa’s colours of red and white matched Coke’s and Coca-Cola even patented a special shade of red, which was used for both its bottle labels and its Santas.

In the campaigns, we can see Santa enjoying a Coke in a crowded department store, downing a Coke having paused his sleigh to read children’s letters, raiding refrigerators in the homes he visits, and – Coke in hand – wishing America’s troops well in World War II.

An image of St Nicholas as Santa Claus from 1906

Coca-Cola’s Santa appeared in magazine ads, on billboards and in store displays, helping – before TV or the internet – to spread a commercialised, and some might say, Americanised Christmas around the planet. Santa can nowadays be seen from Mexico to southern India to Japan. Santa jostles for position with traditional Christmas gift givers like the Three Kings in Spain and Baby Jesus in Portugal. Some nations try to balance the jolly red American hegemony with their older customs – in Venezuela, the traditional Baby Jesus graciously supplies gifts to Santa to distribute to the nation’s children.

Santa Claus pauses on his rounds to sup a Coca-Cola

Old Father Christmas has outwitted his Puritan detractors. Santa/Father Christmas has succeeded in getting us to indulge in gift giving and seasonal cheer. It’s estimated Christmas generates over $1 trillion in retail sales in the USA and £2 billion in the UK. But not everyone has been convinced by Christmas’s jolly red hybrid. In late 19th century England, one Yorkshireman recollected his youth thus:

‘Children knew nothing about Santa Claus or Christmas trees – those are German innovations that should have been left to the Germans. We believed that Old Father Christmas brought our presents and put them in our stockings, which we hung at the foot of our beds.’

Here Santa prefers Coca-Cola to whisky and mince pies

(The images in this article from the Coca-Cola Santa Claus ads can be found at https://www.coca-colacompany.com/stories/coke-lore-santa-claus.)

Leave A Comment