In Emily Brontë’s 1847 novel Wuthering Heights, one of the most important characters is the house of Wuthering Heights itself. Yes, we have the strong-willed Cathy, the callously passionate Heathcliff, the robust yet sullen Hareton, but the house looms over the novel in a way perhaps no human character can.

Covered with gothic carvings; isolated high on a gloomy moor; lashed by wind, snow, sleet and rain; the house of Wuthering Heights sets the harsh, claustrophobic tone that permeates the book. Stronghold-like, it repels outsiders and traps its inmates in a prison of intense passions, deadly jealousies and murderous resentments.

Emily Brontë first shows us the house through the eyes of Heathcliff’s southern tenant Lockwood. Used to a kinder landscape and gentler social codes, the soon-shaken Lockwood struggles to comprehend Wuthering Heights and its inhabitants.

‘Wuthering’, Lockwood tells us, ‘is a provincial adjective, descriptive of the atmospheric tumult to which its station is exposed in stormy weather. Pure, bracing ventilation they must have up there at all times.’

As he approaches Wuthering Heights on his first visit to his landlord, Lockwood notices ‘the excessive slant of a few stunted firs at the end of the house; and a range of gaunt thorns all stretching their limbs one way; as if craving the alms of the sun.’

He remarks on the house’s fortress-like qualities: ‘the architect had the foresight to build it strong; the narrow windows are deeply set in the wall, the corners defended with large jutting stones.’

Arriving at the Heights, Lockwood states, ‘Before passing the threshold I paused to admire a quantity of grotesque carving lavished over the front and especially about the principal door, above which, among a wilderness of crumbling griffins and shameless little boys, I detected the date 1500 and the name Hareton Earnshaw.’

Inside Lockwood finds a basic and cheerless dwelling and far-from-welcoming residents. He also discovers Wuthering Heights has its ghosts. During Lockwood’s second visit, the weather turns hostile: ‘on that bleak hilltop, the earth was hard with a black frost and the air made me shiver through every limb.’

A snowstorm starts up and – as Lockwood would likely die trying to navigate through the drifts back to the house he has rented – Heathcliff reluctantly allows him to stay the night. A servant leads Lockwood upstairs to a chamber, telling him it’s a room her ‘master had an odd notion about … and never let anybody lodge there willingly.’

Lockwood settles himself in an ‘old-fashioned boxbed’, which – built around a small window – ‘formed a little closet’. After bizarre and violent dreams, Lockwood is woken – or thinks he is woken – by what he assumes is a fir branch tapping the window with its cones.

He finds himself ‘knocking my knuckles through the glass, and stretching an arm out to seize the importunate branch; instead of which, my fingers closed on the fingers of a little, ice-cold hand! The intense horror of nightmare came over me. I tried to draw back my arm, but the hand clung to it, and a most melancholy voice sobbed, “Let me in! Let me in!”’

‘Who are you?’ Lockwood asks.

‘“Catherine Linton,” it replied shiveringly … “I’m come home, I’d lost my way on the moor.”’

‘It is twenty years …’ the ghost moans, ‘I’ve been a waif twenty years!’

So far, so very gothic. But was the house of Wuthering Heights simply formed in the turmoil of Emily Brontë’s imagination? Or – during the wanderings she loved to take over the wild moors around Haworth – might Emily have been inspired by any real-life dwellings, dwellings that could have prompted her to create a house that has ever since haunted literary history?

Any such houses would need a suitably dramatic and lonely location, as well as a good bit of grotesque gothic carving and perhaps some wind-crippled trees nearby. They’d have to be stoutly built, strong enough to repulse both the moorland weather and the intrusions of curious outsiders. A history of human misery and struggle and the odd ghost story wouldn’t go amiss. We’d also need to know how such houses were entangled with the lives of Emily and the other Brontës and whether the histories and relationships of the families who lived in them were strange and tortured enough to make them models for the characters in Emily’s novel.

Three houses are acknowledged as candidates for Wuthering Heights:

- High Sunderland Hall, a now demolished gothic manor house on a hill above Halifax

- Ponden Hall, below the village of Stanbury, also seen as a model for the novel’s other dwelling, Thrushcross Grange

- Top Withens, a ruined farmhouse on the moors near Haworth

Read on as we compare their competing claims and along the way explore accounts of ghostly disembodied hands, phantom white horses, weird mottos, obscene carvings, lightning blasts, libraries of black magic books, priceless first editions of Shakespeare, the beginnings of Brontë mythmaking, and tough lives on the moors of Yorkshire.

Did Emily Brontë Base Wuthering Heights on High Sunderland Hall? Rude Carvings, Spectral Hands and a Haunted Hilltop

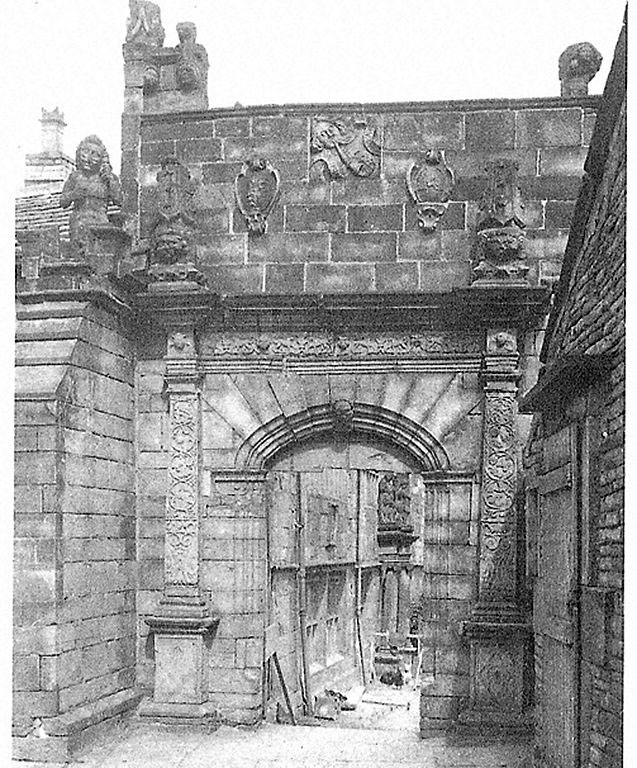

A photo of High Sunderland Hall taken in 1913 – a model for Wuthering Heights?

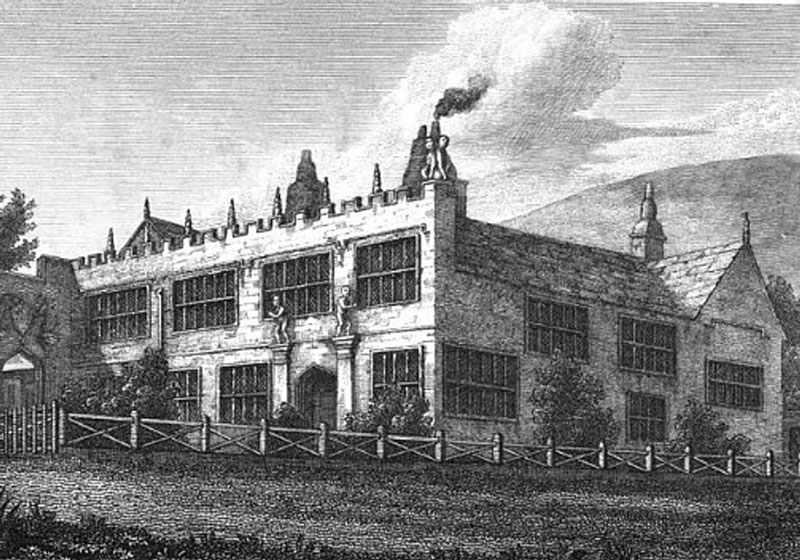

Now sadly demolished, High Sunderland Hall was a wonderfully gothic monstrosity that loomed lonely and high above Halifax. Robustly built, gloomy and battlemented, this house might well have inspired Emily Brontë’s descriptions of a fortress-like abode.

The age of the house was uncertain. High Sunderland Hall may have been constructed for either for Richard Sunderland in 1587 or for his grandson Abraham Sunderland in 1629.

There is, however, evidence of a structure on the site dating back to 1274. Rather than a new building being erected, an existing timber farmhouse may have been encased in stone, perhaps marking the success of the Sunderlands in the local wool trade. In a northern-gothic version of nouveaux-riche extravagance, High Sunderland Hall was covered in the most curious carvings and weirdest mottos.

Surviving photos show strange figures above the Roman-style columns of the main doorway. Winged, muscular and naked; twisting as if trying to avoid harsh winds and whipping rain; these figures look like giants to me, but might the ‘shameless little boys’ of Wuthering Heights be based on them?

The doorway of High Sunderland Hall – did its carvings inspire the ‘shameless little boys’ of Wuthering Heights?

Over the same doorway was a pagan-looking carving of the sun. The house’s decoration also included griffins, Green Men, a trumpet-blowing angel, coats of arms and various mythological creatures.

In 1838, Emily Brontë started teaching at Law Hill School in Southowram, around a mile (1.6 kilometres) from High Sunderland Hall. Though unhappy at the school – she apparently told her pupils she preferred the housedog to them – she loved the local landscape and tried to forget her misery by walking and riding around it. She would have certainly noticed the castellated edifice of High Sunderland Hall glaring down from its hilltop. She may have even been a guest at the house as its floorplan was apparently similar to the layout she gave Wuthering Heights.

High Sunderland Hall had its ghost stories. According to one, a master of the Hall wrongly suspected his wife of infidelity. In a jealous rage, he chopped off her hand and thereafter a ghostly disembodied hand haunted High Sunderland Hall. Guests sleeping in a certain room would sometimes awake to hear footsteps in the passageway, followed by a fumbling at the door and a rattling of its handle. If the spook failed to gain admittance – presumably guests were advised to lock the door against it – a few moments later there’d be a tap on the window. If the guest was brave enough to pull the curtains back, they’d see a disembodied hand rapping against the pane before terrifying laughter resounded.

Could this story have inspired Lockwood’s dream of grasping Cathy’s freezing fingers through the window? Might Emily Brontë herself have stayed in that room?

Strange carvings above a gateway at High Sunderland Hall

A sinister gothic mansion like High Sunderland Hall would, of course, collect tales of ghosts. In addition to the legend of the disembodied hand, a spectral white horse was rumoured to haunt the Hall’s surroundings. This equine phantom could apparently be glimpsed dashing through nearby fields and lanes at midnight. A local newspaper article of 1973 mentioned this apparition, though it stated no one had seen it in living memory. This prompted a letter to the paper from a man who claimed a white horse had galloped past him when he’d been walking home one night. Fearing the riderless horse might cause a traffic accident, the man called the police. Despite a thorough search of the area, no such horse was found.

The strangeness of High Sunderland Hall was perhaps emphasised by the mottos the Sunderlands carved upon it. This oddly poetic inscription was written in Latin on the house’s front wall: ‘May the Almighty grant that the race of Sunderland may quietly inhabit this seat, and maintain the rights of their ancestors free from strife, until an ant drink up the waters of the sea, and a tortoise walk around the whole world.’

Beneath the trumpet-blowing angel – also in Latin – was written: ‘The fame of virtue is an eternal trump.’

Another, Gospel-inspired, inscription stated: ‘He that loves lands and houses more than me is unworthy of me.’ Yet another carving admonished: ‘This place hates negligence, loves peace, punishes crimes, observes laws, honours virtuous persons.’

The inside gateway of High Sunderland Hall – note the two ‘crumbling griffins’ that may have inspired Wuthering Heights.

Unfortunately for the Sunderlands, they didn’t have to wait for a tortoise to walk around the world or for an ant to drink up the sea before they lost their house. During the English Civil War (1642-9), the family head Langdale Sunderland – contrary to most of his fellow West Riding wool merchants – backed the King rather than Parliament. Langdale fought for his monarch as captain of a troop of horse under the Earl of Newcastle and was traumatised by his experiences of battle. With Parliament becoming the stronger party, Langdale received a heavy fine in 1646 and had to sell High Sunderland Hall.

The house passed through a variety of owners. By the beginning of the 20th century, High Sunderland Hall had been divided into tenements. It gradually fell into disrepair and mining works weakened the house’s foundations, leaving it teetering and dangerously unstable. Photos of the Hall shortly before its demolition in 1951 show its walls and pillars bulging outwards.

As High Sunderland Hall became increasingly decrepit, its owner – obviously aware of its resemblances to Wuthering Heights – attempted to sell the building, both to the Brontë Society and Halifax Corporation. But, as the cost of repairs was estimated to be greater than the house’s value, the structure was demolished.

A sketch of High Sunderland Hall made in 1818, the year of Emily Brontë’s birth

One of the Hall’s gothic doorways is said to grace a building in the nearby town of Brighouse. Some of High Sunderland’s carvings were salvaged and are kept at Shibden Hall Museum, near Halifax, in a courtyard. This ensemble of masonry includes strange faces, monsters’ heads, helmet-topped coats of arms and the leaf-covered face of a Green Man.

There are also carvings that can only be described as ‘graphic’ – bare bottoms, naked bodies complete with male genitals. A couple of figures resemble the female ‘fertility symbol’ the Sheela-na-gig, which can sometimes be spotted in churches. Like the Sheela-na-gig, these figures seem to be pulling open their vulvas, but their faces look more male than female. Could all these indelicate carvings have helped inspire Wuthering Heights’ ‘shameless little boys’?

The site on which High Sunderland Hall stood is bleak, wind-blasted, almost treeless. No trace of the Hall is left, but this stark haunted hilltop would be a close match for the setting Emily Brontë gave Wuthering Heights.

Did Ponden Hall Inspire Wuthering Heights? Boxbeds, ‘Bog Bursts’ and Black Magic Books

Did Ponden Hall inspire Emily Brontë to create Wuthering Heights? (Photo: brontecountry)

In an account published in 1896, one William Davies described a visit he made to Haworth in 1858. William met Emily Brontë’s clergyman father Patrick – ‘a dignified gentleman of the old school’ – and together they went on a tour of the area:

‘On leaving the house we were taken across the moors to visit a waterfall which was a favourite haunt of the sisters … We then went on to an old manorial farm called “Heaton’s of Ponden”, which we were told was the original model of Wuthering Heights, which indeed corresponded in some measure to the description given in Emily Brontë’s romance.’

This ‘Heaton’s of Ponden’ was actually Ponden Hall. Sturdily built of dark stone, Ponden Hall sits on the slopes of a hill and boasts stunning views over the Worth Valley. A sizeable – though not enormous – house, with mullioned windows, beamed ceilings and stone-flagged floors, Ponden Hall occupies an area of 5,000 feet and has four acres of grounds. The house overlooks Ponden Reservoir (created in the early 1870s), formerly a smaller lake called Ponden Water. The Hall does have some similarities to Wuthering Heights – it’s robust, it’s of around the right dimensions and its floorplan roughly corresponds to that of Emily Brontë’s fictional dwelling. Ponden Hall’s homely interior might also recall the modest interior of the Heights though its fittings are probably cheerier than those of that sombre farmstead.

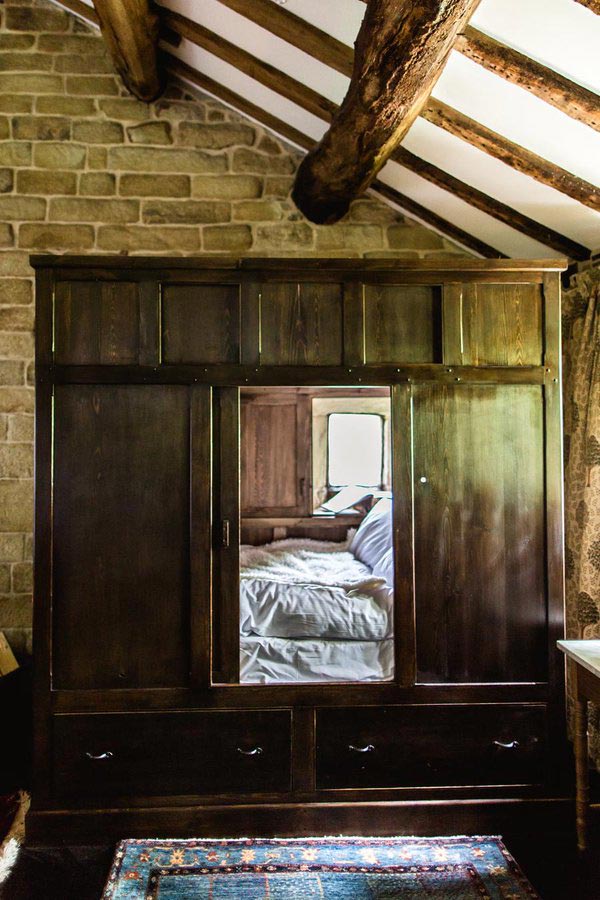

But there’s another feature of Ponden Hall, a feature that conjures up one of the most dramatic and eerie scenes from Wuthering Heights. A bedroom – now called the Earnshaw Room – has a small window inside ‘an old-fashioned boxbed’, similar to the window through which Lockwood feels the dead Cathy’s hand. Though the current boxbed is a replica, the aged original apparently lasted until the 1940s. Another window in the same room – a mullioned one in the east end gable – also has a Wuthering Heights connection. Emily Brontë sketched this window when she was ten and some see it as the model for the notorious window of Wuthering Heights.

The boxbed and its window in Ponden Hall, inspiration for Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights? (Photo: Julie Akhurst annebronte.org)

Ponden Hall, however, lacks the grotesque gothic carvings of High Sunderland Hall and – as far as I know – cannot claim any ghosts. But the factor most against Ponden Hall as an inspiration for Wuthering Heights is its location. Rather than commanding an exposed moortop position, Ponden Hall sits snug and sheltered on a slope near the valley floor. Ponden Hall is indeed thought by some to be a more likely model for Thrushcross Grange, the civilised and luxurious home of Cathy’s husband Edgar Linton (see below). Emily Brontë also makes no mention of Wuthering Heights being close to a lake.

Perhaps Ponden Hall – rather than being a close model for Wuthering Heights – had more of an influence on the Brontës’ general development as writers. The Brontës were friends of the Heatons – the wealthy landowners and industrialists who owned Ponden Hall – and were frequent visitors to the house.

A dramatic demonstration of the friendship between the Heatons and Brontës occurred on 2nd September 1824. A young Emily was walking on the moors with her sister Anne, her wayward brother Branwell and two servants after days of unrelenting rain had cooped them up in Haworth Parsonage. The group were enjoying the fresh post-deluge air and the weak rays of the sun, when the sky suddenly darkened and an ominous rumble came from the earth.

It grew darker still, hailstones pelted down and the ground began to shake. Ponden Hall was in the distance and the group instinctively sprinted towards it as shouts from the Hall urged them on. Panting, hearts pounding, the group reached the Hall, taking shelter in a building called the Peat Loft. Seconds later, an enormous explosion erupted. A torrent of mud and water surged across the landscape they’d just been walking over – a torrent so forceful it picked up large boulders, carried them along and even hurled them into the sky. Patrick ran from Haworth Parsonage, believing his children were victims of an earthquake. He later preached a sermon about their deliverance, which went on to be published. The explosion was heard as far away as Leeds and you can still see the scars and craters this huge landslide – known as the Crowhill Bog Burst – left on the moors.

Ponden Hall had a grand library, said to be the finest in West Yorkshire. This library was frequented by the Brontë sisters, Branwell and Patrick. A catalogue of the library shows that – as well as a precious Shakespeare First Folio – it contained many gothic novels and books on necromancy and black magic. Perhaps such dark literature helped inspire the gothic tinges in the Brontës’ novels. Shortly after Lockwood’s arrival at Wuthering Heights, the younger Cathy scandalises the pious old servant Joseph by taking ‘a long, dark book from a shelf’ and saying, ‘I’ll show you how far I’ve progressed in the Black Art … I’ll have you all modelled in wax and clay.’ ‘Oh, wicked! Wicked!’ Joseph mumbles, ‘May the Lord deliver us from evil!’ Ponden Hall’s library also held volumes on law and local history, and knowledge of these subjects – especially the complexities of inheritance law – would have helped Emily Brontë write Wuthering Heights.

There was also the influence of the Heatons themselves, a notable local family who served as Justices of the Peace and as churchwardens at Haworth, where Patrick was perpetual curate. Behind Ponden Hall stands a withered pear tree, supposedly a present to an unimpressed Emily from a teenage Heaton who had a crush on her. Another story states that Emily was one day taking tea at the Hall when a dog gave birth to puppies at her feet. Robert Heaton was embarrassed, but Emily merely laughed. (In Wuthering Heights, Lockwood remarks that under a dresser there ‘reposed a huge, liver-coloured bitch pointer surrounded by a swarm of squealing puppies, and other dogs haunted other recesses.’) The men from Ponden Hall may have inspired the character of Edgar Linton, the master of Thrushcross Grange and Cathy’s loving, civilised but overdelicate husband. Then again, some have noticed the similarity between the names ‘Heaton’ and ‘Hareton’ – as in Hareton Earnshaw, the eventual heir to Wuthering Heights.

Might Ponden Hall have been a model for Thrushcross Grange? Like the Grange, Ponden Hall had a long tree-lined drive. (Most of the drive has now been swallowed by the reservoir). Also, like Thrushcross Grange, Ponden Hall has a large upstairs room with a window at either end. But Ponden Hall isn’t large enough to be a blueprint for the palatial Grange and it doesn’t have enough grounds. In Wuthering Heights, Thrushcross Grange’s park is so vast one has to walk two miles to get from the keeper’s lodge to the house and the younger Cathy rarely leaves it during her first 13 years. The nearby – and grander – Shibden Hall might be a closer model for the Grange while the size, style and details of Ponden Hall are more similar to Wuthering Heights. Emily might have visited Shibden Hall (now the museum which houses the relics from High Sunderland) when teaching at Law Hill. But Ponden Hall may still have seemed grand to the Brontë sisters, who were used to the much plainer Haworth Parsonage. The tree-lined drive may have also made Ponden Hall seem more imposing than it actually was.

Another Brontë whose writing felt the influence of Ponden Hall and the Heatons was Branwell. Branwell wrote a ghost story about a Gytrash, a type of a shape-shifting Yorkshire spirit which usually manifests as a black dog. Branwell’s Gytrash frequently took on the form of ‘an old dwarfish and hideous man, as often seen without a head as with one’. His story was originally called Heatons at Ponden and based around Ponden Hall. He later changed the title to Thurstons of Darkwall, probably to avoid libelling the Heatons. Branwell also once sketched a hunting party in front of Ponden Hall’s fireplace and was often a guest at pre-hunt gatherings there.

The story of the Heatons and Ponden Hall is, however, ultimately a sad one. Though they owned land stretching to the Lancashire border, the Heatons earned most of their money from Ponden Mill, situated below Ponden Hall at the hill’s bottom. The Heatons did especially well making uniforms for the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15). They showed off their wealth by embarking on extensive renovations to Ponden Hall. Though most of the house was built in 1634 and parts date back to 1541, the Heatons in 1801 started a massive rebuilding programme.

A grand new entrance and the impressive library were constructed and the Peat Loft (built in 1680) was joined to the rest of the house. (The Peat Loft was once a separate two-storey structure, designed to store peat upstairs and shelter cattle downstairs, with the heat from the cows rising to dry the peat.) A plaque above Ponden Hall’s entrance dates the rebuilt house to 1801, the year in which Wuthering Heights starts.

The friendship between the Heatons and Brontës, however, ended when Robert Heaton – who served as churchwarden at Haworth – fell out with Patrick. The quarrel’s cause is unknown, but it was bitter enough for Patrick to refuse to bury him. As far as business was concerned, cheap cloth imports from India forced the Heatons to sell Ponden Mill and saw the family’s wealth much reduced. By the end of the 19th century, just three Heaton brothers were left. One had lost his wife and children in one of the great cholera epidemics Haworth was infamous for; the other two were childless bachelors. In 1898, the last Heaton died. Ponden Hall and its lands were sold off, the furniture was auctioned and – perhaps most tragically – the library was broken up.

The library books found their way to nearby Keighley Market, where any unsold books were ripped apart and used to wrap vegetables. During all this upheaval, the Shakespeare First Folio – a copy from the 1623 print run of what’s considered the first reliable edition of Shakespeare’s plays – disappeared. Only 228 First Folios are known to have survived and are each worth around £3.5 million today. Perhaps the lost Folio is mouldering in some Yorkshire cellar after being used to wrap cabbage.

Ponden Hall was heavily restored around the year 2000 and is now a Bed and Breakfast. Guests can sleep in and wander through the rooms in which the Brontës studied and socialised.

(A significant amount of the research about Ponden Hall and its Bronte connections mentioned in this article was originally conducted by Julie Akhurst, who spent 23 years living at the house.)

Did Emily Brontë Model Wuthering Heights on Top Withens? Lightning Blasts, Moorland Tragedies and the Beginnings of the Brontë Mythos

Did the lonely farmhouse of Top Withens inspire Emily Brontë? (Photo: Sean Martell)

Top Withens is a ruined farmhouse on an isolated, wind-battered moor about five kilometres (3.1 miles) south-west of Haworth. Two weather-misshapen trees stand next to the house, recalling the ‘gaunt thorns, stretching their limbs one way’ Lockwood noticed.

Originally called Top of th’ Withens, the house was probably built by the Bentley family in the late 1500s. In the Brontë era, it was occupied by Jonas Sunderland and his wife (from 1813) and then their son Jonas from 1833.

The setting of Top Withens matches the remote moortop location of Wuthering Heights. The house probably, however, became associated with Brontë legend due to an endorsement from Ellen Nussey, a lifelong friend of Charlotte Brontë. Ellen seems to have suggested to Edmund Morison Wimperis, an artist commissioned to illustrate the Brontë novels in 1872, that Top Withens had inspired Wuthering Heights.

But there’s no mention of Top Withens in any of the Brontës’ writing or correspondence and no evidence they ever visited the place. Its ruins seem far too small and modest to be those of a substantial farmhouse like Wuthering Heights. Top Withens’ internal layout was also nothing like that of the house described in Emily’s novel. The Brontës would, however, have probably been aware of Top Withens and passed it on their walks. The farm’s inhabitants and the Brontës may have known each other, at least by sight.

A well-tramped tourist path – signposted in English and Japanese – runs to Top Withens from Haworth. This path would seem to take visitors on a journey through the Brontë mythos, as it passes the Brontë Waterfall then goes over the Brontë Bridge and past the Brontë Chair, a seat-like chunk of rock the sisters supposedly took turns to sit in to compose their early stories. But anyone expecting to find Wuthering Heights at the end of their trek might be disappointed. A plaque fixed to the ruins of Top Withens states:

This farmhouse has been associated with “Wuthering Heights”, the Earnshaw home in Emily Brontë’s novel. The buildings, even when complete, bore no resemblance to the house she described, but the situation may have been in her mind when she wrote of the moorland setting of the Heights.

— Brontë Society 1964. This plaque has been placed here in response to many inquiries.

Top Withens may, nevertheless, have had something else in common with Wuthering Heights: the difficult lives of its residents and their struggles against the moorland weather.

Things seem to have been tough from the start. In 1591, William Bentley split his Withens estate between his three sons, creating three smaller farms at Lower, Middle and Top Withens. The dividing up of inheritances was common in the South Pennines, but it had the unfortunate result that each generation was left with less land. This led to greater hardship and many moorland farmers relied on quarrying and weaving to top up their meagre incomes. The Worth Valley surrounding Top Withens is scarred by worked-out quarries. As Lockwood stumbles home in deep snow following his traumatic night at Wuthering Heights, he speaks of ‘entire ranges of mounds, the refuse of quarries’ that the snowfalls have ‘blotted from the chart which my yesterday’s walk left pictured in my mind.’

By the late 1880s, the area around Top Withens had been christened Brontë Country and had begun to appear in guidebooks. This didn’t, however, make life easier for locals. In 1888, Top Withens passed to Anne Sharpe (née Sunderland) and her husband Samuel. A report on May 18th 1893 in the Todmorden and District News about a thunderstorm showed what they were up against. A lightning bolt had struck the farm – blasting holes in the wall and tearing part of the roof off, with the wind then flinging the slates down into the valley. The bolt smashed the flags paving Top Withens’ floor and shattered around 30 windows. In the kitchen, the heat melted a knife blade and Anne’s dough bowl was destroyed. Howling and screeching, the dog and cat ran from the house.

By 1895, Anne was dead, leaving Samuel to raise their daughter Mary. But life at Top Withens proved too tough. In 1896, Samuel and Mary fled to a farm down in the valley named Sheep Holes.

Did Top Withens’ isolated moorland setting influence the location of Wuthering Heights? (Photo: Dave Dunford)

There were people willing to step into their place. Top Withens appears to have been occupied until around 1890. In 1903-4, however, Keighley Corporation bought the now-decaying Withens farms. Top Withens seems to have stayed vacant until the early 1920s, when an invalided ex-solider called Ernest Roddie moved in. Ernest lived in his hilltop retreat with just his dogs and chickens, and – intrigued – the Yorkshire Post sent a reporter up to interview him.

Ernest said, ‘I think Top Withens is the place for me, alright. We have some rough weather up here … it’s been fearful cold since Christmas and there are days when the snow’s been so thick I couldn’t get the cart down to Stanbury.’

‘But,’ Ernest continued, perhaps referencing the tourists who found their way up there, ‘a man can’t be lonely at Wuthering Heights.’

The interview took place after Ernest had only endured one winter. By 1926, the weather had beaten him too and he moved down to Haworth. In 1930, the buildings at Lower and Middle Withens were demolished and the doors and windows of Top Withens were sealed to discourage vandals.

Top Withens received a grade-II listing in the 1950s, but this was revoked in 1991 as the dubiousness of its Brontë connections became increasingly apparent. Some ill-judged repairs with concrete have done little to enhance any notion of historical authenticity.

But still the Brontë fans, the literary tourists, the merely curious hike out of Haworth to examine the ruins of what’s still widely credited as ‘Wuthering Heights’. Perhaps that moortop, those twisted trees, that lingering sense of tragedy and hardship all make Top Withens just too good a relic to lose its Wuthering Heights tag.

So What House Inspired Emily Brontë to Create Wuthering Heights – High Sunderland Hall, Ponden Hall or Top Withens?

If I had to pick a house as the inspiration for Wuthering Heights, I’d choose High Sunderland Hall. Its dimensions and layout were about right. It had a suitably stark moortop setting, plenty of gothic ornamentation and even a window-tapping ghost.

But it’s also possible that, on her moorland tramps, Emily was taken with the lonely location of Top Withens. In addition, Ponden Hall may have provided Lockwood’s boxbed and window, Catherine’s black magic books, the models for some characters, and maybe some of the interior details of Wuthering Heights.

Perhaps in Emily Brontë’s mind, all three houses became fused with elements drawn from her potent imagination, leading her to conjure one of the most ominous houses to have ever haunted a book.

As the enduring popularity of Wuthering Heights suggests, there is something about that house and its moorland surroundings that will always fascinate readers and keep drawing them back. As Emily Brontë wrote: ‘Heaven did not seem to be my home; and I broke my heart with weeping to come back to earth; and the angels were so angry that they flung me out into the middle of the heath on top of Wuthering Heights; where I woke sobbing for joy.’

(This article’s main image shows Top Withens, a building widely credited as ‘Wuthering Heights’. Photo: Steve Calcott)

I sincerely doubt Wuthering Heights was based on any singular house. It seems most likely to me that Emily created a fictional house, inspired by the ways of living she’s seen around her. She likely took elements from different houses (such as the box bed with the mirror) and was inspired by the tales she heard. But if you want to find a one-on-one match, you’re doing her creation short. She created a fictional house that could exist on the Moors, rather than using one that already existed.

Hi Cinder, if you read the article, you’ll see I’m not suggesting a one-on-one match – the purpose is rather to suggest houses that might have influenced Emily’s rich imagination when creating Wuthering Heights. She was likely influenced by several real-life dwellings, but – of course – also by her imaginative and literary gifts.

I loved this article it was fascinating, and I do believe that Emily probable did draw inspiration from the houses you have described. I love Wuthering Heights, Emily’s writing is dramatic and ominous. I recently visited Haworth for the first time, It’s such an atmospheric place. The weather was too bad for a jaunt on the moors, but I plan on returning often to explore the area more and immerse myself in Emily’s vivid imaginative writing. Thank you for this article, it has certainly inspired me to delve further.

Thanks Ellie, so glad you enjoyed it. Haworth certainly is atmospheric!

Absorbed by all things Bronte for many years (and having directed a stage adaptation of ‘Jane Eyre’) I thought this article absolutely riveting! I am stunned by High Sunderland Hall – having only recently discovered it in other writing – I feel deeply that this is EB’s main inspiration for Wuthering Heights – the clues are all there including the jaw-dropping story of the ghostly hand, for gawd’s sake! Of course, she must have picked up other things from other houses (the box bed etc, although there might well have been one at High Sunderland) but this incredible building, still haunting my imagination now, must have – in its gaunt and near-abandoned state, absolutely galvanised the supra-heightened heart and mind of Emily. I don’t think I’ve read anything quite so ‘up my street’! I think High Sunderland Hall needs its own story told, incorporating its aristocratic owners, the ghost(s) and Emily Bronte herself….!

Hi, Joanna, yes, High Sunderland certainly had a fascinating history and is an extremely strong contender as inspiration for Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, especially with its ghostly tapping hand!