Towards the end of the 1600s, in what would become the London suburb of Camden Town, the most incredible event is said to have taken place. At a crossroads – on the site of what’s now Camden Town Tube Station – stood a ramshackle cottage, a dwelling infamous amongst those who lived nearby. The cottage was the home of an old woman locals called Mother Damnable: a witch, most claimed, also a murderer and poisoner, many asserted. This woman was so thoroughly wicked that – according to ‘an old pamphlet’ – one day in the late 17th century: ‘Hundreds of men, women and children were witnesses of the Devil entering her house in his very appearance and state, and that although his return was narrowly watched for, he was not seen again, and that Mother Damnable was found dead on the following morning sitting before the fireplace holding a crutch over it with a teapot full of drugs, herbs and liquid.’

Legend has indeed given Mother Damnable a notorious reputation. Her parents, it’s said, were hanged for causing a young girl’s death by witchcraft and her lovers either met gruesome ends or mysteriously vanished. Three were reputedly dispatched by her hand, with the charred body parts of one being discovered in her oven. She’s alleged to have given shelter to the infamous female bandit Moll Cutpurse. In her old age, when rumours of her dabbling in the black arts were at their most intense, Mother Damnable was blamed for any misfortune that befell the inhabitants of Camden Town. (Then little more than a hamlet and collection of alehouses scattered around a crossroads on a northerly route into London.) The villagers would apparently gather outside the witch’s cottage and berate her. Mother Damnable would respond by leaning from her window and flinging foul abuse. Usually, the appearance of her huge, vicious black cat – widely thought to be a devilish familiar – sent the yokels scurrying.

But was Mother Damnable really a practitioner of black magic? Was she a murderer? Did she exist at all? Was she perhaps a composite of several infamous females? Why was she associated with a pub that remained notorious for centuries after her death? What was Mother Damnable’s connection with the renowned Yorkshire fortune teller Mother Shipton and what did Dracula author Bram Stoker have to say about her? And why might rumours of witchcraft have attached themselves to such a person in the first place? Read on for tales of gallows, hairless cats, bat-embroidered cloaks, spooky crossroads and weird potions.

Mother Damnable’s Notorious Parents and her Four Dead or ‘Disappeared’ Lovers

According to the legends, Mother Damnable’s real name was Jinney – or Jinny or Jenny – Bingham. Though records of her birth have either been lost or never existed, she seems to have been born around 1600. She was the only child of a brickmaker, Jacob Bingham, from Kentish Town, which was the nearest settlement of any size to Camden. Her mother was the daughter of a Scottish peddler, who Jacob met while serving in Scotland in the army. His military service over, Jacob returned to the Camden Town area with his Scots wife and resumed his brickmaking trade. The couple and their young daughter, however, would sometimes travel around the country to peddle Jacob’s wares.

At about 16 years of age, Jinney Bingham became pregnant by her boyfriend, a man known as ‘Gypsy’ George Coulter. Her father built the couple a cottage on a patch of waste land, commonly believed to be the spot now covered by Camden Town Tube Station. (Though some say the cottage stood on the site now occupied by the – perhaps appropriately named – World’s End pub just across the road.) George’s residency in the cottage would prove a short one. Accused of stealing sheep near Holloway, he was tried at the Old Bailey and hanged at Tyburn (A notorious place of execution close to Marble Arch). Jinney next took up with a man named Darby, a heavy drinker. Their relationship soon became full of furious arguments and violent confrontations. After one particularly brutal incident, Jinney is said to have sought her mother’s advice on how to deal with her drunken lover. Darby vanished shortly afterwards. No one knew what had befallen him and no investigation was conducted into his disappearance.

But Jinney was about to lose more people in her life. Her parents were ordered to appear in court, accused of killing a young girl by means of witchcraft. The two were found guilty and hanged. Jinney, perhaps to fill the emotional gap left by their execution, began cohabiting with a man named Pitcher. As with her liaison with Darby, their relationship soon degenerated into a series of arguments and fights. Pitcher, like his predecessor, wouldn’t be part of Jinney’s life for long. Unlike with Darby, however, it soon became clear what had happened to him. Pitcher’s body was discovered – charred and toasted – in Jinney’s oven.

As there was a body, there could be an investigation and Jinney Bingham was put on trial for Pitcher’s murder. Things were looking grim for her until an associate popped up in the witness box. This acquaintance said Pitcher had a habit of hiding in the oven to escape Jinney’s savage tongue. Perhaps, having done this, he’d fallen asleep and his roasting had merely been an accident. The court was convinced and Jinney was acquitted.

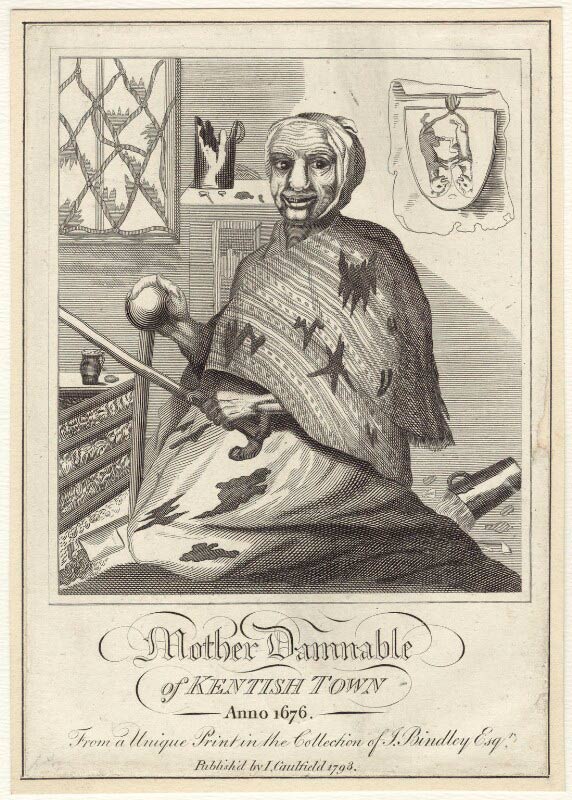

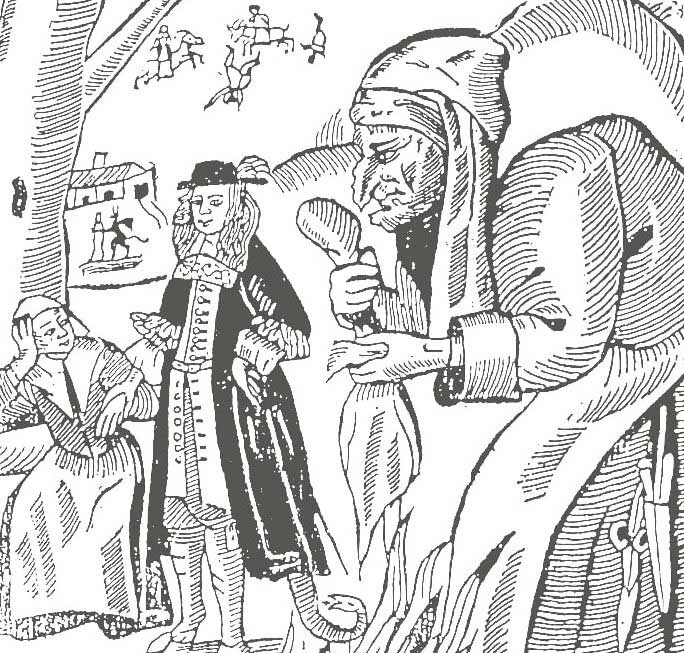

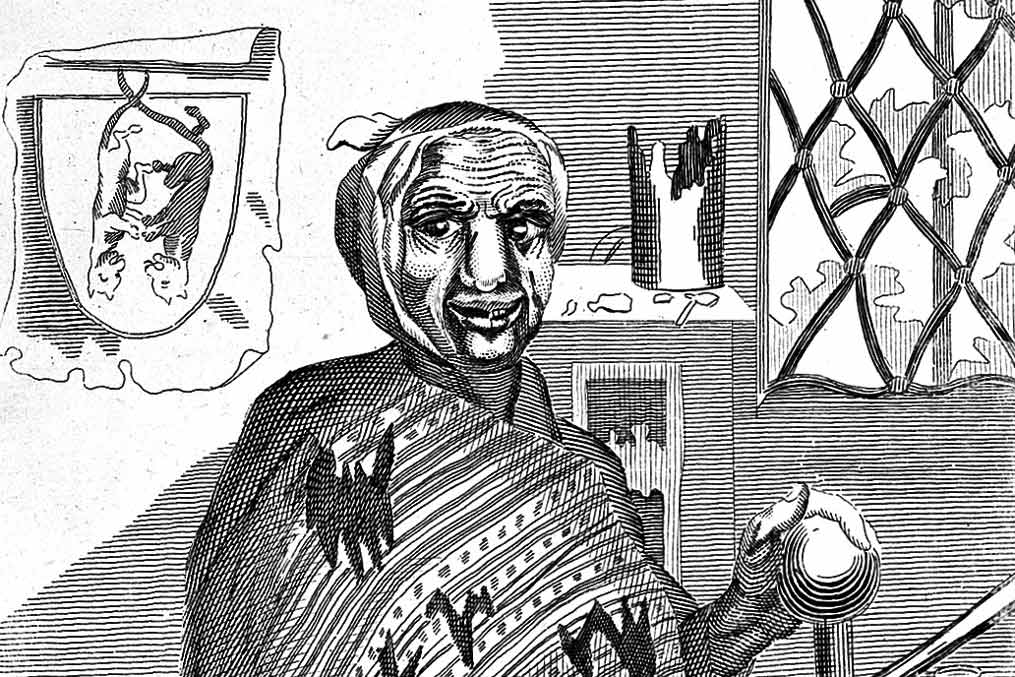

An image of ‘Mother Damnable of Kentish Town’, said to be from 1676

Despite her evasion of the noose, the trial ruined Jinney’s – already far from spotless – reputation in her neighbourhood. People avoided her and she became more reclusive. She’d normally wait until nightfall to leave her home, when fewer people were around. Nobody could say for certain how she supported herself, a fact which likely gave rise to more gossip. It was around this time she acquired certain nicknames – Mother Damnable, Mother Redcap and the Shrew of Kentish Town. (In that era, a ‘shrew’ was an ill-tempered, aggressive woman prone to nagging and scolding, as in Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew.)

In the 1640s, during the English Civil War, the reclusive Jinney Bingham was surprised by an urgent banging on the door of her cottage. She opened it to see a man who begged her for shelter, claiming he was being pursued. Jinney gave him lodgings and the man – who turned out to be wealthy – became her lover. Moll Cutpurse – a notorious thief who wore men’s clothing, smoked a pipe and pimped both male and female prostitutes – sometimes stayed with them during the Civil War and its aftermath. Jinney’s wealthy lover would, however, prove little better at getting on with her than her previous partners. Though their vitriolic relationship dragged on for many years, he eventually died. The villagers suspected Jinney had poisoned him. Their claims were investigated, but the inquest decided there was insufficient evidence to support this allegation. Around this time, rumours grew up that Mother Damnable – as her parents had – was meddling in the black arts. Such gossip would dominate the later years of Jinney Bingham’s life.

Mother Damnable’s Old Age, Reputation for Witchcraft and Devilish Death

As Mother Damnable aged, she became ever more reclusive. Usually, just her large, vicious black cat provided her with company. Villagers did, however, sometimes sneak in to see her thanks to her reputed skills as a teller of fortunes and – according to Samuel Palmer’s local history book St Pancras (1870) – ‘a healer of strange diseases’. The same residents, however, scapegoated her for anything that went wrong – the death of a cow or child, perhaps, or the failure of a business or crops.

Palmer stated that ‘when any mishap occurred, then the old crone was set upon by the mob and hooted without mercy. The old, ill-favoured creature would at such times lean out of her hatch-door, with a grotesque red cap on her head.’ The cap was said to be worn to hide her baldness. Palmer goes on to describe Mother Damnable as having ‘a large broad nose, heavy shaggy eyebrows, sunken eyes and lank and leathern cheeks; her forehead wrinkled, her eyes wide and her looks sullen and unmoved. On her shoulders was thrown a dark grey striped frieze, with black patches, that looked from a distance like flying bats. Suddenly she would let her huge black cat jump upon the hatch by her side, when the mob instantly retreated from a superstitious dread of the double foe.’

Despite her age and isolation, Mother Damnable never seemed to want for anything. The house, having been built by her father, was hers and she presumably either made sufficient money from fortune-telling and herbalism or had enough left over from her rich boyfriend. She probably died around 1680 and, according to legend, the Devil was seen coming to collect her wicked soul and she was found with a concoction of herbs still bubbling over her fire.

Samuel Palmer quotes from the ‘old pamphlet’ describing the witch’s demise. According to this text, one of those who discovered Mother Damnable thought it would be a good idea to give some of her potion to the cat. The feline’s ‘hair fell off in two hours, and the cat soon died’. Mother Damnable, the pamphlet continues, ‘was stiff when found, and … the undertaker was obliged to break her limbs before he could place them in the coffin and … the justices have put men in possession of the house to examine its contents.’

Palmer concludes by asserting: ‘Such is the history of this strange being, whose name will ever be associated with Camden Town, and whose reminiscence will ever be revived by the old wayside house, which, built on the site of the old beldame’s cottage, wears her head as the sign of the tavern.’

The above account is the story of Mother Damnable as popularly understood in legend. But how true might such a tale be and – if it is more folklore than fact – what could have influenced the evolution of this weird myth? Let’s investigate in the next sections.

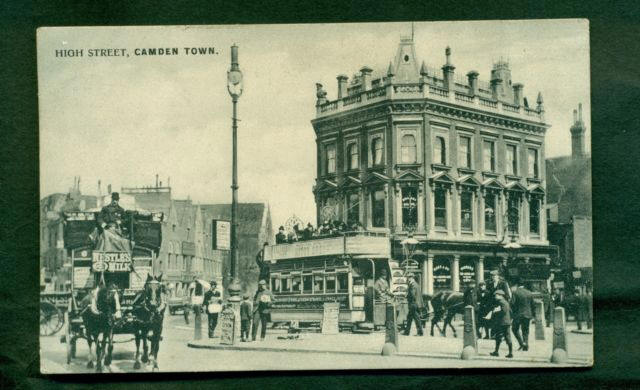

Camden Town Tube Station – built over the home of the notorious witch Mother Damnable? (Photo: Sunil060902)

Might Mother Damnable Have Been a Fearsome, Foul-Mouthed, She-Dragon of an … Innkeeper?

In this strange case, it might be wise to see to how much we can tease out the possible narratives of Mother Damnable, Mother Redcap, the Shrew of Kentish Town and Jinney Bingham, see how far they go back and question to what extent these different names might be referring to the same person.

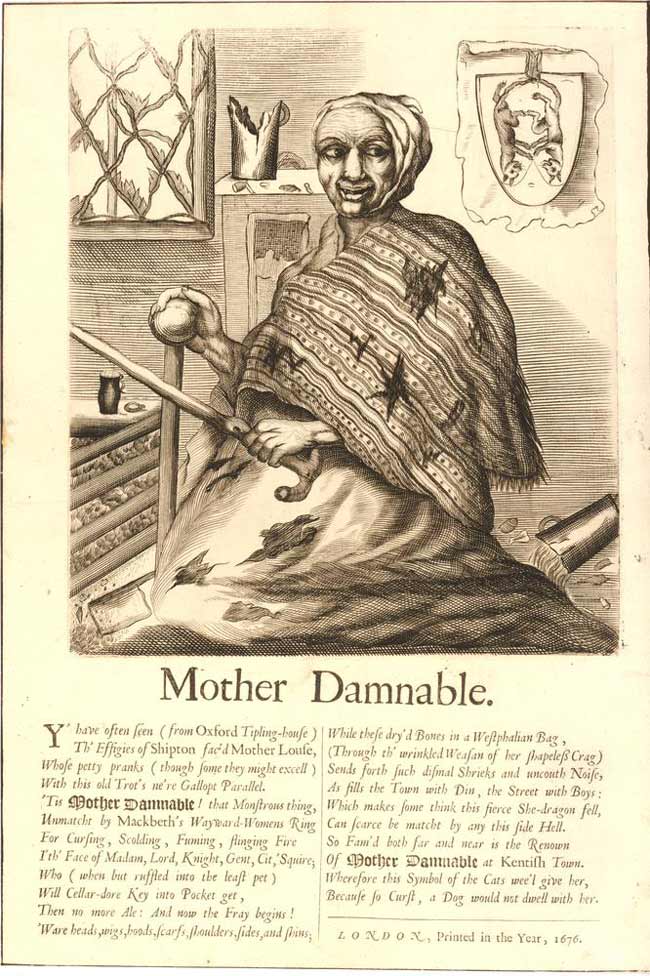

A Mother Redcap is mentioned in a letter said to have been sent from Whitehall by one Henry Foxhall to Charles Firebrace in 1666, but perhaps the most interesting early sources depict a ‘Mother Damnable of Kentish Town’. These sources, consisting of pictures and a satirical rhyme, are dated 1676 and probably came from a broadside. (Broadsides were single sheets of paper hawked in the streets and printed with poems, news or ballads.) The earliest copies of the 1676 sources we have, however, are from 1793. They appear in James Caulfield’s Portraits, Memoirs, and Characters of remarkable Persons, from the Reign of Edward III to the Revolution; collected from the most authentic accounts, which seems to have been published in batches between 1790 and 1795.

The pictures show Mother Damnable as a witchy-looking old woman in patched threadbare clothes seated close to a fire, but the accompanying rhyme appears to depict her as a foul-mouthed, combative pub landlady rather than a worker of magic. We learn that Mother Damnable was prone to ‘cursing, fuming, flinging fire in the face of Madam, Lord, Knight, Gent, City Squire’. We also learn that whenever she was ‘ruffled into the least pet, will cellar-dore key into pocket get, then no more ale, And now the fray begins!’ During this ‘fray’, customers are warned to beware of ‘heads, wigs, hoods, scarfs, shoulders, sides and shins’. As the fracas unfolds, the ‘fierce she-dragon’ Mother Damnable ‘sends forth such dismal shrieks and uncouth noise, As fills the town with din, the street with boys.’

The satirical rhyme about ‘Mother Damnable of Kentish Town’. The spilt and broken tankards in the background might also indicate she was the landlady of a rowdy establishment.

So how might this ‘Mother Damnable of Kentish Town’, this terrifying landlady, connect with the witch of Camden Town, Jinney Bingham? Caulfield – who claimed to have acquired the pictures and rhyme from the collection of a ‘J. Bindley Esq’ – states that Mother Damnable’s real name was unknown. But beneath one of the pictures is written: ‘Mother Damnable, the remarkable shrew of Kentish Town, the person who gave rise to the sign of Mother Recap on the Hampstead Road, near London, an dom 1676.’

I suspect this caption was written by Caulfield or some other later writer rather than dating to the late 1600s. The language – though I wouldn’t claim to be an expert – doesn’t sound like 17th-century English and the tense would indicate it was written after Mother Damnable’s death. (The tenses used in the verse, on the other hand, make it sound like Mother Damnable is vigorously alive, as she might well have been in 1676.) What Caulfield, or whoever wrote the caption, is doing, however, is making an explicit connection with a pub that stood for a long time at the crossroads where Jinney Bingham’s cottage is once said to have been located. (Now either the site of Camden Town Tube Station or the World’s End.) This pub – also for a long time – seems to have been called The Mother Red Cap (or Old Mother Red Cap), which – as we’ve seen – was another of Jinney’s nicknames. The satirical rhyme links Mother Damnable to Kentish Town rather than Camden, but as Camden Town was so small in those days it was often lumped in with its more sizeable neighbour. So it’s possible the pub of the notorious alewife of the Mother Damnable rhyme might have been situated at Jinney’s crossroads – and the alewife herself might have been Jinney.

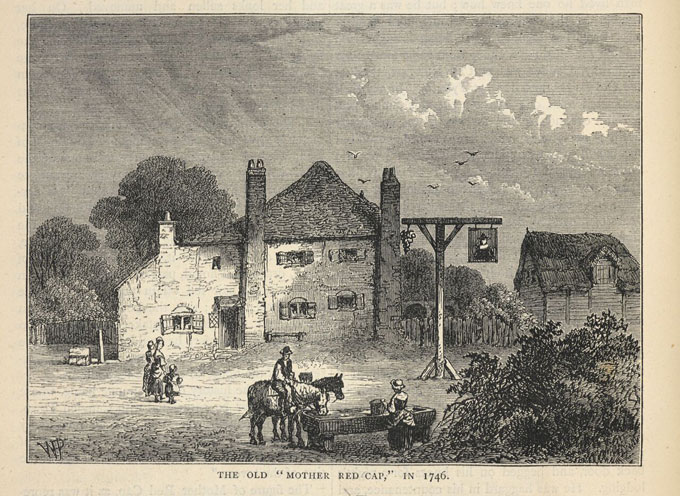

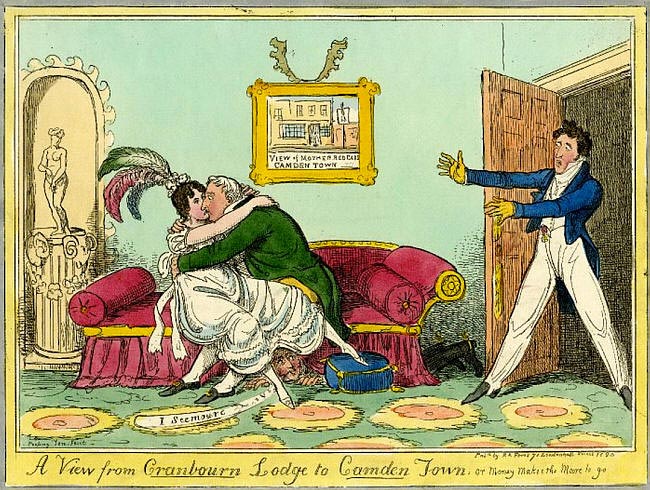

The first known reference to a pub in this location is from 1690. Though we can’t know what the pub was named in such times, the idea seems to have arisen that it was long called the Mother Redcap after a notorious ex-owner. A sketch reputedly from 1746 names the pub the Old Mother Redcap while a cartoon from 1820 includes a painting of the pub with that name (though minus the ‘Old’). In his Book for a Rainy Day or Recollections of the Events of the Years 1766-1833 (1905), J.T. Smith wrote that the Mother Red Cap had a terrifying reputation as ‘it has been stated that “Mother Red Cap” was “Mother Damnable” of Kentish Town in early days, and that it was at her house that the notorious “Moll Cut-purse”, the highwaywoman of Oliver Cromwell’s days, dismounted and frequently lodged.’ In Old and New London (1878), Edward Walford reports that ‘the old house was taken down, and another rebuilt on its site, with the former sign, about the year 1850. This again, in its turn, was removed; and a third house, in the modern style, and of still greater pretensions, was built on the same site a quarter of a century afterwards.’

The sign – which always seems to have been rescued from any demolition and displayed outside each version of the Mother Red Cap – according to Walford: ‘Exhibited that venerable lady – whether she was alewife or witch – with a tall, extinguisher-shaped hat, not unlike that ascribed to Mother Shipton.’

A bucolic sketch of the Mother Red Cap, said to be from 1746

So Jinney Bingham – if that was indeed her name – might have been an innkeeper rather than a witch. If Jinney was an innkeeper, one would suspect she’d have presided over a less than respectable hostelry, perhaps some sort of grog shop. (Maybe, due to the tavern’s prominent location, though, the madams, lords and gents of the rhyme occasionally wandered in – to be quickly repulsed by the landlady and clientele.) A character running a rough pub popular with travellers and criminals might well – like the Jinney of legend – have possessed a robust will, volatile temper, razor-edged tongue and propensity to undertake occasional violent acts. The supposed location of Jinney’s cottage – on the corner of a busy crossroads on a route into London – seems to me a more likely site for an alehouse than a ramshackle witch’s dwelling. It’s hard to imagine such a piece of prime real estate being a scrap of waste ground on which a poor workman might erect a humble house for his daughter. Jinney’s giving of lodgings to people – like Moll Cutpurse and the Civil War fugitive – might also suggest innkeeping was her occupation. In addition, ‘Mother Redcap’ was a common nickname bestowed on female innkeepers from the late 1500s onwards. The name is mentioned, for instance, in a 1595 jestbook, a 1597 play and a 1656 ballad. It seems that only in the 1800s did the name Mother Redcap cease to denote an innkeeper and start denoting a witch.

Cartoon of 1820 showing a picture of the Mother Red Cap in Camden Town

But might there not have been some indications of witchiness around this ferocious landlady? It’s been suggested that alewives were perceived by some to have a witchy aura. They owned cats to keep rodents away from the malt, wore tall black hats so they’d stand out in the marketplace, used broom-like braided twigs to remove yeast from fermented beer and displayed magical-looking stars as a sign of their ale’s purity. Furthermore, the 1676 rhyme compares Mother Damnable to other notorious females – Mother Shipton, Mother Louse and ‘Macbeth’s wayward women’. Mother Louse was another infamously ugly and sharp-tongued alewife, but Mother Shipton (of whom we’ll hear more later) and the women mentioned from Macbeth were seen as witches. It’s unlikely, however, that the author of the rhyme was seriously suggesting Mother Damnable was a witch. Though by 1676 the persecution of witches had lost some of its intensity, executions for witchcraft continued into the early 1700s and those suspected of this offence were despised social outcasts. No one would have wanted to drink in a bar run by a witch. What the broadside might have done, however – especially if it had sold well – was put the idea in some minds that there was some link between witches and Mother Damnable and – as we’ll see below – this association may have grown stronger over the centuries.

So How Did Mother Damnable Come to Be Seen as a Witch and What Did Mother Shipton Have to Do with It All?

The 1676 sources depicting ‘Mother Damnable of Kentish Town’ – assuming the materials James Caulfield acquired for his book were genuinely from around that date – would suggest there might have been a formidable landlady with that nickname and that she might have run a pub on Jinney’s crossroads. But, as we’ve seen, these sources describe her as alewife rather than witch. They also make no mention of her slaying her lovers, of her parents being hung for practising the black arts and of the Devil’s remarkable visit to her cottage on the day of her death.

Most of what we know today about the Jinney Bingham/Mother Damnable character comes from Samuel Palmer’s 1870 book, the full title of which is the snappy St Pancras, Being Antiquarian, Topographical, and Biographical Memoranda, Relating to the Extensive Metropolitan Parish of St Pancras, Middlesex, with Some Account of the Parish from Its Foundation (St Pancras was the large semi-urban parish that then included Camden Town). Palmer appears to have been the first to link the name Jinney Bingham with the Mother Damnable figure. The only reference to sources he makes, however, is his mention of the ‘old pamphlet’ describing Mother Damnable’s death. I haven’t been able to find any earlier references to this pamphlet. Some of the descriptions Palmer gives – the likening of the patches on the cloak to bats, for instance – smack more of Victorian Gothic Romanticism than how people would have perceived witches in the 1600s. (Palmer – a writer, painter and disciple of William Blake – was an important figure in the English Romantic movement.)

We might suspect, then, that the shrewish and combative aspects of Jinney Bingham/Mother Damnable stemmed from the attributes of a real person and only in the Victorian age became mingled with legends of witchcraft. This could have been thanks both to a misunderstanding of the term Mother Redcap, the meaning of which had changed over time, and the Romantic Victorian embellishments of writers like Samuel Palmer. (The letter from Henry Foxhall, though supposedly sent in 1666, actually first appears in a book published in 1843, perhaps suggesting some gothic Victorian enhancements may have taken place with that correspondence.) From Palmer’s descriptions of Mother Damnable, it would seem he was familiar with the pictures published by Caulfield. Could Palmer have observed Mother Damnable kneeling before the fire and allowed his gothic imagination to invent her teapot full of ‘drugs, herbs and liquid’? (Palmer and other later writers perhaps also converted Mother Damnable’s inclination for casual violence into a string of murders.)

The English Romantic Samuel Palmer (1805-81) in a self-portrait of 1826. Palmer did much to popularise the tale of the Camden Town witch Mother Damnable.

It is possible, however, that Palmer drew at least some of his material from local oral traditions. The turning of Mother Damnable into a witch was probably not a completely Victorian innovation. To understand how this switch of identity may have come about, we’ll need to turn our attention again to Camden Town’s inns. One such tavern had a very similar name to the Mother Red Cap: the Mother Black Cap.

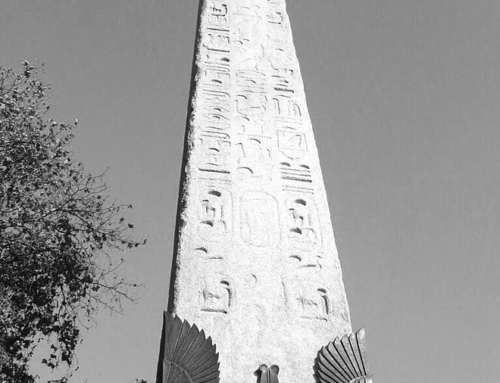

The Mother Black Cap seems to have been established by about 1750. It must have been in existence by 1830 at the latest, as a manuscript from around that date mentions both the Mother Black Cap and Mother Red Cap in a list of Camden Town’s pubs, along with eight other hostelries with names like the Laurel Tree, the Hope and Anchor, and the Elephant and Castle. The Mother Black Cap, according to Walford, stood ‘at the northern or upper end of the High Street’. Mother Blackcap was a common name for Mother Shipton, a semi-legendary witch and fortune teller with astounding prophetic powers said to have lived between 1488 and 1561 and to have been born near Knaresborough, Yorkshire. Walford comments, ‘It is not a little remarkable that two inns bearing the names of these semi-mythical ladies exist within half-a-mile of each other.’

The first records of Mother Shipton and her prophecies appeared in 1641, 80 years after her reported death. By this stage, accounts of the prophetess would have passed somewhat into the realms of the mythic. Though Mother Shipton was generally seen as a less malevolent character than Jinney Bingham/Mother Damnable, the legends of the two enchantresses have certain aspects in common. Mother Shipton was also said to be hideously ugly, she knew the medicinal properties of plants and herbs, and – like Jinney Bingham – she suffered ostracisation because of her ugliness and reputation as a witch. Her husband died young and – as with the Shrew of Kentish Town and her lovers – some suspected Mother Shipton of causing his death. The Devil was also rumoured to be involved in Mother Shipton’s story. Some said Mother Shipton sold him her soul in exchange for her weird powers; others that her mother Agatha had been seduced by the Devil or had summoned him herself, with their union resulting in the birth of the strange child that would grow up to be Mother Shipton. Like Mother Damnable, Mother Shipton foretold the future, though her prophecies tended to be grander than Mother Redcap’s predictions about her neighbours’ affairs. Mother Shipton predicted the first piped water system in York, Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries and Break with Rome, and the spectacular growth of the capital: ‘Shall Highgate Hill stand in the midst of London’. Several accounts have her casually assigning a date for the Apocalypse. Despite her fame as a witch, Mother Shipton, like Mother Damnable, wasn’t put to death. She died peacefully in her bed at an old age.

The famous Yorkshire witch Mother Shipton – a model for Camden Town’s Mother Damnable?

We might wonder why a witch from the north would have a pub named after her in Camden Town. Mother Shipton did have a nationwide fame. D.C. Mackay, in his Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions (1841), wrote, ‘The prophecies of Mother Shipton are still believed in many of the rural districts of England. In cottages and servants’ halls, her reputation is still great; and she rules, the most popular of British prophets, among all the uneducated and half-educated portion of the community.’ Her popularity in the north, however, seems to have been especially strong.

In his 1910 book Famous Imposters, the author of Dracula Bram Stoker devoted a chapter to Mother Damnable’s legend. Stoker felt the Mother Black Cap pub was likely so-named because ‘Camden Town was a suburb through which the northern traffic passed on its way to and from London.’ It was, therefore, ‘wise to use for publicity and entertainment names that were familiar to north country ears. Before the railways were organised the great wheeled and horse traffic between London and the North – especially Yorkshire which was one of the first Counties to take up manufacturing and the wool trade – went through Camden Town. So it was wise forethought to take as an inn sign a Yorkshire name. The name of Mother Shipton had been in men’s mouths and ears for about two-hundred years, and as the times had so changed that the old stigma of witchcraft was not then understood, the association with Knaresborough alone remained.’ As for Mother Damnable’s reputed end, Stoker wryly comments, ‘What a pity it was that no veracious scribe or draughtsman was present in the crowd which had noticed the Devil’s entry into the house. In such a case we might have got a real likeness of His Satanic Majesty – a thing which has long been wanted – and the opportunities of obtaining which are few.’

So, in Camden Town, two public houses were named after notorious women of legend. One – the Mother Black Cap – was named after Mother Shipton, a well-known soothsayer and witch, whereas the other – the Mother Red Cap – may have been christened in honour of Jinney Bingham/Mother Damnable, a sharp-tongued shrew with a reputation for violence who, nonetheless, might not have originally had associations with magic. Despite this, there were similarities in the two women’s legends and both pubs’ landlords – according to Stoker, ‘open and avowed trade rivals’ – likely used those legends to promote their competing establishments. Over time, the two ladies with similar names – who also, excepting the colour of their headgear, probably looked similar on their pub signs – may have been confused by the residents of Camden Town and the travellers that stopped there. Bits of Mother Shipton’s myth could therefore have sneaked into the folklore surrounding Mother Redcap. (Perhaps building on the tenuous links already made as long ago as the 1676 broadside.) In this way, witchcraft might have been added to the list of fearsome attributes the sword-tongued shrew possessed. Victorian writers may have then applied a gothic gloss to the legend of Mother Damnable, giving it its current form.

The Black Cap pub in Camden Town, which closed in 2015, was a descendant of the Mother Black Cap.

Of course, the Mother Damnable character might over the years have accumulated aspects of several women. A number of scholars – including the folklorists Steve Roud and Jacqueline Simpson and the historian John Callow – do see Mother Damnable as a composite figure of two or more individuals. Mother Louse has already been mentioned and it’s also been suggested that one of the models for Mother Redcap was a follower of the Duke of Marlborough’s army during the Reign of Queen Anne (1702-14). In Holloway, not far from Camden Town, a coin or token is said to have been discovered dated 1667 and crudely stamped with the inscription ‘Mother Read Cap’s in Holloway.’ Another possible prototype for the Mother Redcap myth was an alewife named Eleanor Rumming of Leatherhead, Surrey, who lived in the reign of Henry VIII. The poet John Skelton (c.1463-1529) described Eleanor as being ‘ugly of cheer, her face all bowsy, wondrously wrinkled, her een bleared, and she grey-haired.’ It’s interesting, though, that none of these women seem to have been associated with witchcraft, a fact that would perhaps support the idea that the witchy aspects of Mother Damnable were imported into her myth thanks to Mother Shipton and a confusion – especially after a few ales – of pub signs. But is this necessarily the case or might parts of Mother Damnable’s legend really match up with deep folkloric notions of the magical and attitudes towards witches that were current in the 1600s? Let’s try to find out below.

Crossroads, Black Cats, Scapegoats and the Coming of Capitalism – How Might the Mother Damnable Legend Match up with the Folklore and History of Witchcraft?

Although the Jinney Bingham/Mother Damnable legend might have arisen in the Georgian and Victorian epochs from the fusing of various elements – and various semi-historical figures – certain things about her mythos do equate with folkloric notions of witches and the historical knowledge we have of those who tended to be accused of witchcraft.

Mother Damnable owned a black cat and such felines already had their reputation as sinister beings and witches’ familiars in the 1600s. It’s possible, however, that the cat was later added to her myth. It’s also interesting that her cottage was said to have stood at a crossroads. Crossroads, perhaps because they symbolise the intersection of different realities or realms, are in many parts of the world seen as magical sites. In England, they were reputed to be places where magical rituals occurred. They were also sites where suicides were buried and gallows and gibbets set up. This was partly due to the belief that the unquiet ghost of the suicide or executed convict would be confused by the choice of four ways and therefore wouldn’t wander off to haunt nearby settlements. There were indeed once plans to erect a gallows at Mother Damnable’s crossroads. In 1776, The Morning Post stated, ‘Orders have been given from the Secretary of State’s office that the criminals capitally convicted at the Old Bailey shall in the future be executed at the crossroads near the “Mother Red Cap” inn, the half-way house to Hampstead, and that no galleries, scaffolds or other temporary stages be built near the place.’

Ye Olde Mother Red Cap in 1930 opposite Camden Town Tube Station. Some, however, say the station itself was the site of the original tavern.

It seems these gallows were either never erected or never used. This may have been because of the popularity of the site with Londoners. In Old and New London Walford wrote, ‘At the beginning of the present (19th) century the “Mother Red Cap” was a constant resort for many a Londoner who desired to inhale the fresh air and enjoy the quiet of the country, for at that time the old tavern – which, by the way, was also known as the half-way house to Highgate and Hampstead – stood almost in open fields and was approached on different sides by green lanes and hedgerow roads. At that time too, the dairy over the way, at the corner of the Chalk Farm, or Hampstead, or the Kentish Town Roads, was not the fashionable establishment it afterwards became, but partook more the character of “milk fair” … for there were forms for the pedestrians to rest on, and the good folks served out milk fresh from the cow to all who came.’ This bucolic scene perhaps contrasts with some of the crossroads’ more sinister associations and Smith’s depictions of the Mother Red Cap as a terrifying inn.

A postcard showing the Ye Olde Mother Red Cap pub in Camden Town around 1925. The pub is listed under that name in directories from the 1930s and 1940s. In 1985, it was renamed The World’s End.

Returning to Mother Damnable, though, research by historians – such as Keith Thomas in his Religion and the Decline of Magic – indicates that in the Early Modern Period (1500-1700) certain types of people were more likely to be accused of witchcraft. Though individuals of any age, sex or social rank could have the charge of witchcraft levelled against them, older poor women were much more frequently accused. This was largely because the emergence of the capitalist system was leading to a more individualistic and money-orientated outlook on life. The old feudal bonds of community were weakening and people were less inclined to give charity to their poorer neighbours. And the poorest of all tended to be old, often widowed women, who had no one to support them and to whom the economic and social structures of the time gave little opportunity for employment. But the old ways of thinking hadn’t gone entirely so when such people turned up begging at their neighbours’ doors and were sent away, the neighbours were likely to feel guilt. As so often is the case, this guilt expressed itself as anger and blame towards the victims of the social system. When a mishap occurred – an animal dying, a failure of crops – and the householder remembered the old woman he’d turned away (and perhaps turned away with a good few curses and threats coming from the crone) he might assume she’d cast a spell on him.

It’s interesting that the rumours of Mother Damnable practising witchcraft became more intense towards the end of her life. It’s also intriguing that her neighbours were depicted as harassing her when any of them had suffered a misfortune. What doesn’t fit this narrative, however, is that Mother Damnable never seems to have wanted for anything and was never put on trail for witchcraft. This could indicate that – if one of the prototypes of the Mother Damnable figure was some sort of enchantress – she might have been a cunning woman. Cunning men and women were village folk magicians who used a combination of sympathetic magic, Christian prayers, amulets and talismans, and herbal remedies to help neighbours who came to them in trouble. They might, for instance, cure human and animal diseases, help find lost goods or identify thieves. Though being accused of witchcraft was an occupational hazard for a cunning woman or man, it was something that in fact happened infrequently, perhaps indicating the importance communities placed on such people. The Mother Damnable character’s brewing up of potions, her relative prosperity and the fact she wasn’t tried for witchcraft might suggest that one of the models for her was such a person.

Is Camden Town Tube Station still infused with the dark spirit of the witch Mother Damnable? (Photo: Rossographer)

All this is, of course, speculation and the scarcity of sources from the time she was said to have lived makes it difficult to do more than take educated guesses about Jinney Bingham/Mother Damnable’s identity. But an attempt to understand her strange narrative could run something like this. A female innkeeper in the 1600s – infamous for her sharp tongue, aggressive demeanour and violent tendencies – was so notorious that pubs built on the site of her tavern were thereafter named after her. Her legend thus established, it over the years merged with tales of similar redoubtable alewives and – possibly – with memories of old women accused of witchcraft and cunning folk. The setting up of a rival tavern nearby – called the Mother Black Cap, after Mother Shipton – either introduced magical elements into her myth or enhanced any such elements already there. This was largely due to the public confusing Mothers Blackcap and Redcap and merging their legends, legends which may have already boasted striking similarities. When excitable Victorian writers put a fashionably gothic overlay on it all, the terrifying tale of black magic and villainy was complete.

Gothic garments on sale in Camden Market – does Mother Damnable’s spirit linger in the area? (Photo: Felix Magazine)

I think Camden Town Tube Station is still a strange spot. The atmosphere’s heavy, as if with centuries of foreboding, and the meeting of four roads throbbing with London traffic does give one a feel of a crackle in the air. On a London Underground network replete with tales of ghosts and hauntings, the origin myth of Camden Town Station stands out as especially eerie. Perhaps, also, the spirit of Mother Damnable lives on in the gothic culture the area’s now famous for, with its market stalls of black drapery and witchy trinkets. The psychogeography of Camden’s pubs also hints at an influence from the tutelary spirit of the once notorious innkeeper. There’s the doomily named World’s End; there was until some years ago a pub bearing the name the Halfway House (called now, I think, the Camden Eye, with a somewhat ominous-looking eye painted on its gable). There was also, until 2015, a pub called the Black Cap – a descendant, I believe, of the original Mother Black Cap. This pub was a haunt of the serial killers Dennis Nilsen and Anthony Hardy and Nilsen picked out some of his victims in there. On a less dark note, a pub called the Mother Black Cap appeared in the cult film Withnail and I (1987), set in Camden Town in 1969. The main characters, drink-soaked and drug-infused out-of-work actors, are threatened with violence in the establishment. Perhaps the spirit of Mother Damnable has truly settled on Camden and – despite ongoing attempts to corporatise, sanitise and gentrify the neighbourhood – isn’t going to leave any time soon.

A very informative read, though Camden is not a suburb of London as it’s fairly central and only a 15-minute walk from Euston.

Interestingly, there’s also a Mother Red Cap in Archway which isn’t far from Camden.

Thanks for your comment, Tomo, glad you enjoyed the article. I know Camden – and London – well. I guess the term ‘suburb’ could mean ‘not part of central London’ rather than somewhere on the outskirts. Perhaps ‘a district of Inner London’ would be more accurate though that’s a bit of a mouthful. And, yes, there is a Mother Redcap in the Holloway/Archway area – I believe it gets a mention in the diary of Samuel Pepys.