Manhattan was once intended to host a most macabre monument, a monument that would dwarf the Statue of Liberty and other well-known landmarks. This monument, simply put, would have been an enormous and extravagant tomb – in the shape of an owl.

The mausoleum was designed for the rich newspaper publisher, owl obsessive and notorious playboy James Gordon Bennett Jr. Bennett planned for his tomb to be entirely hollow and – even more strangely – for his coffin to hang in its centre, suspended from the roof by huge iron chains. Far from the tomb being a private place of rest, tourists and city dwellers would be encouraged to enter it. In the hollow interior, a staircase would spiral up from a pedestal and snake around the dangling coffin before ascending to the eyes of the owl. These eyes would be windows, offering vertigo-inducing views over New York.

The site James Gordon Bennett Jr. chose for his flamboyant sepulchre was Washington Heights, part of which was the property of the Bennett family. This piece of land – on 183rd Street and today known as Bennett Park – sits 265 feet above sea level. Altogether – with the owl itself standing at 125 feet and the pedestal at 75 – Bennett’s tomb would have loomed over the city at an incredible (for the time) 465 feet. By contrast, the Statue of Liberty thrusts her flame to a rather stunted-seeming height of just 305.

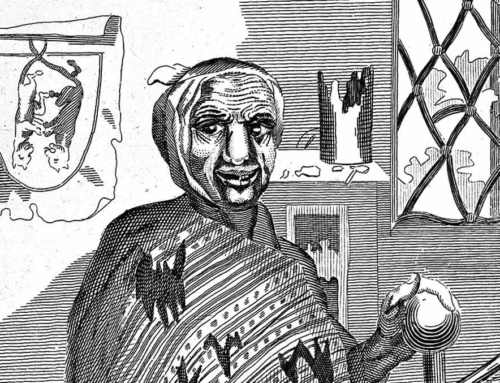

A sketch of the proposed owl-shaped tomb of James Gordon Bennett Jr., by the artist Andrew O’Connor

The man Bennett chose to design his ostentatious mausoleum was Stanford White, a brilliant architect and highly controversial character from the prestigious company McKim, Mead and White. This firm had already designed such notable edifices as Columbia University, the Brooklyn Museum and the second Madison Square Garden and would go on to sketch out the plans for Pennsylvania Station and the New York Public Library. So it’s clear Bennett wished for his mausoleum to be up there among New York’s most impressive structures.

Obviously, a massive owl-shaped tomb doesn’t tower over New York today, but was Bennett’s mausoleum actually ever constructed? Who exactly was James Gordon Bennett Jr., how did he acquire his stupendous wealth and shocking reputation, and where might his spooky obsession with owls have come from? Were any other owls made in response to Bennett’s wishes and can any still be seen peering gloomily down from New York buildings today?

Below is a tale of the jaw-dropping excesses of America’s ‘Gilded Age’, of philandering architects being most publicly murdered, of weird secret societies that used owls as emblems, of Greek goddesses popping up in late-19th-century New York, and of green eyes lit up eerily for over 100 years by incandescent bulbs.

The Privileged, Strange and Outrageous Life of James Gordon Bennett Jr

The source of most of James Gordon Bennett Jr.’s wealth was his newspaper the New York Herald, which he inherited from his father – James Gordon Bennett Sr. – in 1867. Born in Scotland, Bennett Sr. had moved to America at the age of 24 and – after working as a freelance journalist – had founded his own publication. Bennett Sr. possessed the noble idea that ‘the object of the modern newspaper is not to instruct but to startle and amuse’ and the New York Herald duly served up a moreish diet of crime, scandals, gossip and political intrigue. In just its second year, the Herald gained massive sales from its salacious coverage of the murder of a high-class prostitute and year-after-year repeated this feat with similar sensationalist stories. The Herald is also believed to have published the first ever interview in the United States media – conducted with, perhaps unsurprisingly, the madam of a brothel. Some of the Herald’s coverage was so shocking that angry crowds would gather around the newspaper’s headquarters – Bennett Sr. had a supply of weapons stashed in the office to deal with such mobs. By the time Bennett Sr. handed the running of the paper over to James Gordon Bennet Jr., such lurid reporting – along with the ‘penny paper’s’ cheap price – had given the New York Herald the highest circulation in the United States.

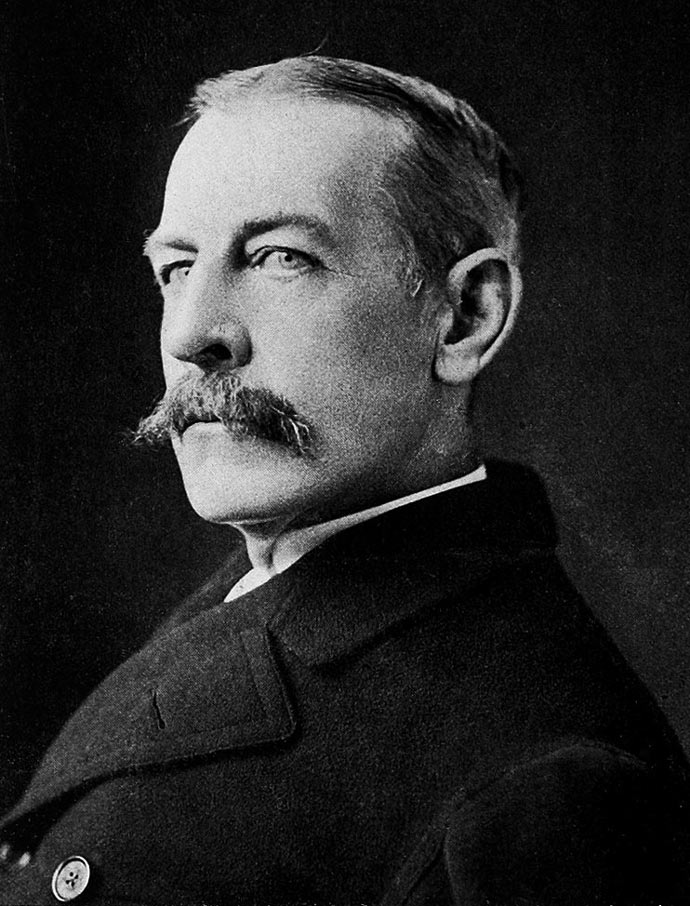

James Gordon Bennett Jr., photographed around 1901

James Gordon Bennett Jr. was, like his father, skilled at sniffing out sensationalist news items, but he certainly didn’t expend all his energies on his work. Bennett Jr. was known around Manhattan for his excesses and oddities. He indulged in all the usual rich boys’ hobbies – polo, hot-air ballooning and tennis as well as enthusiastic drinking and partying. One trick he was especially fond of was racing a carriage and four horses through midnight streets in the nude. Once, in Paris, he had to be taken to hospital – presumably in his birthday suit – after driving under a low arch and bashing his head. Despite all his antics, James maintained a furious work ethic, rising at dawn to deal with business correspondence and articles cabled to him by reporters and editors.

Perhaps his greatest passion was yachting. He learned to sail at a young age, becoming the youngest ever member of the New York Yachting Club at just 16. In 1866, he won the world’s first transatlantic yacht race and he also captained a ship in the Civil War for a year on the side of the Union. Legend states that during this service he was one night woken by a hooting owl – hoots that alerted him his boat was in danger of running aground. (Some say his craze for owls started then.) On his yachts, he entertained bon vivants, artists, painters and even a young Winston Churchill and was known in New York society as ‘the Mad Commodore’ (a commodore being the president of a yacht club).

During the Gilded Age (from around 1870 to about 1890) the American economy boomed and – despite the presence of inequality and poverty – there were fortunes to be made. Those lucky enough to amass – or inherit – such wealth often engaged in idiosyncratic behaviour that mirrored the roaring spirit of the epoch. Another famous New Yorker was the socialite Evander Berry Wall whose offbeat fashions – thigh-length leather boots for himself and collars and ties for his dogs – led to him being nicknamed the King of Dudes. The industrialist C.K.G Billings once threw a dinner party in a Fifth Avenue Ballroom, during which he appeared on horseback and insisted his guests drank their champagne from rubber tyres. Then there was Alva Vanderbilt who – in a huff at not being able to get a private box at the Academy of Music – stormed off to found the Metropolitan Opera. But one particular incident would mark James Gordon Bennett Jr. out from even this crazy cast of rich eccentrics.

On New Year’s Day in 1877, Bennett – completely drunk – staggered into a party hosted by the family of his fiancée Caroline May. There he distinguished himself by urinating into a fireplace (or, some say, a grand piano) in front of all the guests. The engagement was swiftly broken off, but such was the family’s outrage that Caroline’s brother Freddy assaulted Bennett with a horsewhip the next day and even challenged him to a duel. The pair met for pistols at dawn (a practice already considered archaic by that time) and seem to have only avoided killing or injuring each other through being such poor shots. Bennett, though, never recovered his social standing and – the following year – slunk off in disgrace to live in Paris. He’d spend much of the rest of his life in that city or travelling the world on a succession of yachts.

One yacht Bennett acquired during his early years in Paris was the Lysistrata, a 300-foot beast boasting a Turkish bath, a theatre troupe, a luxury French sports car and a crew of 100. The yacht also had its own cow – kept in a padded, fan-cooled stall – so that fresh cream could be served at the captain’s table. Bennett also for a time resided at Louis XIV’s old estate at Versailles, where he entertained regally. He kept his newspaper interests going from exile, founding the Paris Herald and dreaming up new stunts to sell his publications. For one of these, he decided to ‘find’ the explorer David Livingstone in Africa (despite the fact that Livingstone wasn’t actually lost). The journalist Henry Morton Stanley – who supposedly spoke the immortal words ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume’ – was funded by Bennett and the Herald. Bennett also financed an 1879 journey to the North Pole by the navy veteran George Washington de Long. This project was, however, less successful as de Long’s ship was crushed by ice in the Bering Strait, with 20 crew members dying on the freezing trek that then had to be made overland. Bennett’s antics, both personal and professional, were so widely known that it’s though the British expression of shock or surprise – ‘Gordon Bennett!’ – derived from him.

But how did this rowdy character – born into privilege and wealth – end up having such an obsession with owls, an obsession that took him to the point of demanding a massive tomb on prime New York real estate in the shape of one of those birds? What dark and occult meanings do owls have in folklore and mythology and how might these meanings have influenced Bennett? What secret societies in America at that time took owls as their emblems and is their any evidence that James Gordon Bennett Jr. was connected to any of them? Let’s investigate below.

James Gordon Bennett Jr.’s Obsession with Owls, Owls in Myth and Folklore, and Secret Societies with Spooky Owl Emblems

Bennett seems to have harboured an enthusiasm for owls for much of his life, an obsession that only seems to have grown over time. He began keeping live owls in his offices, he wore owl-themed cufflinks and even painted owls on the prow of his beloved yacht, the Lysistrata. He insisted an owl was printed on the masthead of the New York Herald and his newspapers carried articles and editorials arguing for the protection of the birds. When in the 1890s the Herald moved from ‘Newspaper Row’ in Lower Manhattan to a site in Midtown (now known as Herald Square), Bennett asked his friend and drinking partner, Stanford White, to design the new headquarters. Bennett unsurprisingly stipulated that plenty of owls should adorn the edifice.

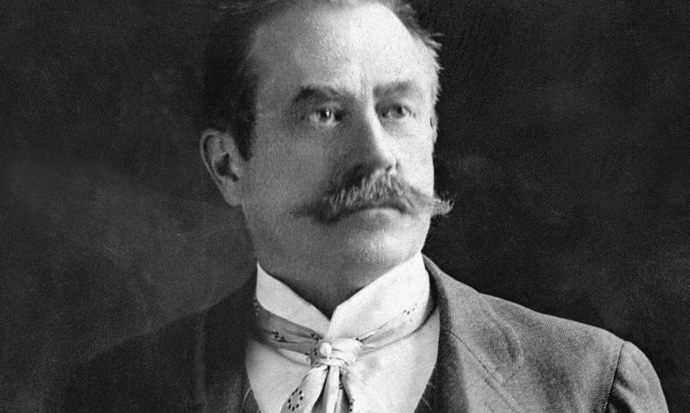

Stanford White, the architect chosen by James Gordon Bennett Jr. to design both the New York Herald Building and his elaborate owl-shaped tomb

Though White based his design on the Renaissance-era Palazzo del Consiglio in Venice, he added some special features. The roofline of the building was strewn with bronze owls – 22 of them in total. Larger owls positioned on the building’s corners had green glass eyes illuminated with incandescent bulbs. A sculpture on the front of the building showed the Roman goddess Minerva positioned behind a large bell, upon which the deity’s attendant owl perched. Two burly typesetters wielding weighty mallets posed by the bell, which they’d ring according to the dictates of a complex mechanical apparatus.

The New York Herald Building, decorated with the statue of Minerva and many owls

This might be a good place to examine the role of the owl in folklore and myth. Minerva is seen as equivalent to the Greek goddess Athena and Athena has long had an association with owls. Owls have traditionally been symbols of wisdom, intelligence, art and scholarship, attributes associated with Athens and its patron goddess Athena, and the city and goddess both indeed had the owl as their emblem. Athens’s Acropolis was even home to a protected flock of the creatures. The owl also, however, has a darker aura of misfortune and death. The Roman poet Ovid (43 BC-17/18 AD) wrote that sighting the bird was an evil omen while his fellow Roman versifier Virgil (70 BC-19 BC) described an owl emitting a death howl from a temple at night, a screech that foreshadowed Dido’s death. According to Pliny the Elder (AD 23/4-79), Rome once had to undergo a cleansing ritual because one of the birds strayed into a temple on the Capitolium. In Kenya, seeing an owl or hearing its hoot means someone is about to die and in English folklore an owl hooting can also mean death. On a slightly more absurd note, Pliny the Younger (nephew of the Elder) claimed owls’ eggs were a good hangover cure.

We can perhaps see some of this folklore and symbolism reflected in Bennett’s life. I’m sure he would have seen intelligence as an important factor in his business dealings even if this virtue wasn’t so evident in the newspapers his company produced. The owl’s associations with death may be linked with his ideas of an extravagant owl-based tomb – he would have likely, being such an owl enthusiast, have known something of the bird’s mythical connections with mortality. Even Pliny the Younger’s notion of the hangover cure may have had some resonance with Bennett’s lifestyle!

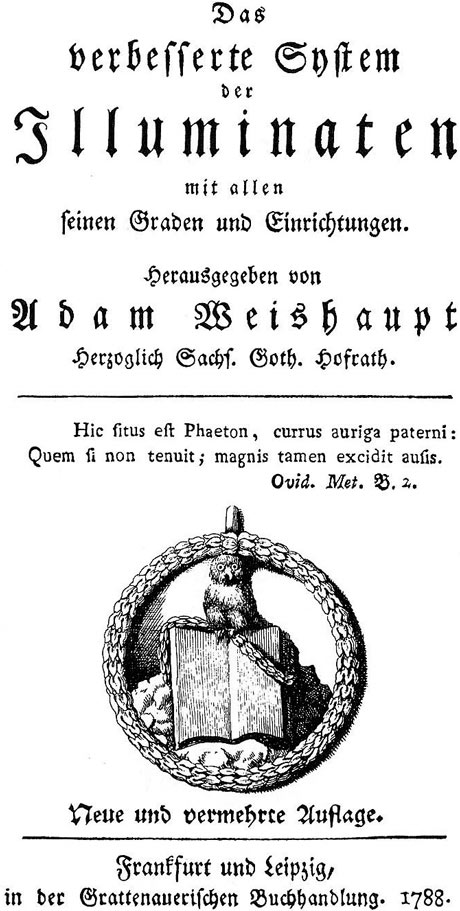

A more fruitful line of enquiry may be, however, to look into the significance of the owl in secret societies. The Bavarian Illuminati – a late-18th-century group that has spawned countless global conspiracy theories about high society plots – had a grade known as the Minerval Academy, whose symbol was an owl. Though quite a low rank in the order, the Academy was important in the education of recruits. Initiates wore medallions that depicted an owl holding open a book – signifying wisdom – and surrounded by laurel leaves, symbolising graduation. The Illuminati also apparently liked the owl because it – like them – performed its important tasks at night and represented caution. Initiates recited a poem by Elizabeth Carter (1717-1806) which included much owl symbolism, with references to the ‘solitary bird of night’ and ‘favourite of Pallas’ (another name for Athena).

The owl of Minerva – on an Illuminati pamphlet – perched on an open book representing wisdom

A secret society that James Gordon Bennett Jr. is more likely to have had contact with, though, was known as the Bohemian Club. This association was a mysterious members’ club for journalists, publishers and those in the arts, and its symbol was an owl. The Bohemian Club – which still exists – states that the owl represents the wisdom of life and companionship, which allows humans to struggle with and survive the frustrations and cares of the world. A replica of an owl statue from the Acropolis adorns the library of the club’s headquarters in San Francisco, and even replicates the Greek bird’s chiselled-off beak. The seal of the Bohemian Club shows an owl and includes the motto ‘Weaving Spiders Come Not Here’. This alludes to an incident in which the mortal Arachne dared to challenge Athena – goddess of arts, needlework and handicrafts – to a weaving contest. Arachne’s impertinence led to her being turned into a spider as punishment. Interestingly, owls are also associated with Lilith, a vegetation demon and – according to Jewish folklore – Adam’s first wife. Lilith is described as a great screeching owl in the Book of Isaiah. A prominent ‘Boho’, the poet George Sterling, wrote a play called Lilith: A Dramatic Poem, in which Lilith mentions the owl, suggesting at least some Bohos knew of this symbolism. Sterling (1869-1926) lived in a private room in the Bohemian Club towards his life’s end, a room in which he – sadly – committed suicide.

Bas relief outside the Bohemian Club headquarters in San Francisco, showing an owl and the motto ‘Weaving Spiders Come Not Here’. (Photo: Binksternet)

The Bohemian Club owns a 2,700-acre campground in Monte Rio, California, known as Bohemian Grove, which is used for the club’s rituals and gatherings. The campground contains a 40-foot statue of an owl, which is the centrepiece of such ceremonies. Annual retreats began there in 1878 and have continued up until the present. In one pageant, a figure called ‘Care’ – representing the woes of life – is mocking burnt at the owl statue’s base. This ceremony was instituted in 1881 by the club’s co-founder James F. Bowman and it still goes on today, enlivened by colourful parades, pyrotechnics and brilliant costumes.

The 40-foot owl statue used by the Bohemian Club in their ceremonies. Was James Gordon Bennett Jr. a member?

It’s unclear whether James Gordon Bennett Jr. was a member of the Bohemian Club, but – with the nature of his work – he must have at least been aware of it and known people initiated into the organisation. The prominent nature of the owl on his planned tomb and the obsessive focus on that same symbol in the Bohemian Club may well suggest some link.

But what did actually happen to Bennett’s outlandish plans for an owl-inspired mausoleum? Was his looming monstrosity ever built and – if not – what eventually happened to Bennett and where was he laid to rest? What about the fate of the Herald’s extravagant owl-festooned headquarters and does anything remain of the building – or its owls – today? Read on and we’ll find out.

An Architect’s Murder, James Gordon Bennett Jr.’s Death and the Fate of His Owl-Shaped Tomb

However ludicrous James Gordon Bennett Jr.’s plans for his owl-like mausoleum might seem, his architects soon started work on the project in earnest. Stanford White hired a sculptor in Paxton, Massachusetts, to come up with designs and an artist, Andrew O’Connor, produced pencil sketches and clay models of the tomb. But an episode in June 1906 – involving the chief architect – would seriously undermine progress on the bird-shaped sepulchre.

White had a reputation for serial philandering and, more darkly, for sexual assaults. White’s home – in the original Madison Square Garden – was topped with a golden statue of the naked goddess Diana while across the park was an apartment in which he met women for erotic rendezvous. This ‘love lair’ – at 22 West 24 Street – appeared dingy from outside, but within was filled with red oriental silks and up-lit works of art. The actress Evelyn Nesbit described entering the apartment as ‘breath-taking … the predominating colour was a wonderful red … heavy velvet curtains shut out all the daylight.’ The bedroom was covered in mirrors and hanging from the ceiling was a ‘gorgeous swing with red velvet ropes around which trailed green similax.’

White had seen Evelyn Nesbit – one of the most famous and photographed actresses and models of the era – on stage and he was enchanted. Though almost three times Evelyn’s age, White deluged her with gifts before inviting her to his apartment where – following a lavish meal – he drugged and raped her. Evelyn, as baffling as it may seem, appears to have stayed smitten with White and the two then carried on a consensual affair that lasted several years.

Evelyn Nesbit – mistress of the architect Stanford White – in 1903

On 25th June 1906, White attended a performance of the musical Mam’zelle Champagne at the rooftop theatre of the old Madison Square Garden. As the show reached its finale, during a song – perhaps ironically – titled I Could Love a Million Girls, Evelyn’s then-husband, the multi-millionaire Harry K. Thaw, walked towards White’s table. Thaw pulled out a pistol, yelled either ‘you’ve ruined my life’ or ‘you’ve ruined my wife’, and fired three shots straight into White’s head, killing him instantly. The lengthy court case that followed gripped the nation, with the sensationalist newspapers – the New York Herald included – proclaiming it ‘The Trial of the Century’ and no doubt making plenty of money from their coverage. With White’s death, Bennett’s plans for his mausoleum were put on hold and in the end it was never constructed.

Bennett himself, surprisingly, settled down, but not until the age of 73, when he married Maud Potter, the widow of George de Reuter from the Reuters news agency. Five years later, in 1918, Bennett died, passing away at his luxury villa on the French Riviera. Bennett was buried in the Cimetière de Passy, in Paris, in a grave far more modest than the towering monument he’d once planned.

But did any of Bennett’s owls survive him? The spectacular, owl-festooned headquarters of the Herald outlasted Bennett by just three years, being demolished in 1921. Despite the effort and expense he’d put into the building, Bennett had only signed a 30-year lease on the land. When asked why the lease was so short, Bennett said, ’30 years from now, the Herald will be in Harlem and I’ll be in Hell!’ But even the New York Herald didn’t survive its energetic owner for long. It ceased publication in 1924, merging into the now-defunct New York Herald-Tribune, though its Paris edition lives on in the form of the International New York Times.

Statue of Minerva and her owl in New York’s Herald Square today. (Photo: ScoutingNewYork)

The Herald Building might have long since disappeared, but some of Bennett’s owls still haunt New York. The statue of Minerva, her owl and the mallet-brandishing typesetters was saved and incorporated into a clock-tower-cum-memorial to Bennetts Jr. and Sr., which can be seen in Herald Square today. Behind the clocktower lurks a door, decorated with an owl perched on a crescent moon and the French phrase la nuit porte conseil, which roughly translates as ‘sleep on it’. The monument also features two of the owls that once embellished the Herald Building’s roof. Their eyes still flicker with an eerie green light, but the birds seem of little interest to the city dwellers, tourists and commuters who hurry by each day beneath. It appears that – for a man who was so ostentatious, influential and wealthy – not a great deal is left of James Gordon Bennett Jr.’s fame.

One of James Gordon Bennett Jr.’s rescued glowing-eyed owls, in Herald Square, New York. (Photo: ScoutingNewYork)

The mysterious owl seal behind the Bennett memorial in Herald Square. (Photo: nycscout)

Another of James Gordon Bennett Jr’s rescued owls – in addition to those on the clocktower, a number are scattered through Herald Square, New York. (Photo: Ephemeral New York)

I can’t help wondering, though, how this might have been different if White hadn’t been murdered and Bennett had succeeded in having his massive mausoleum built. Would Bennett’s owl-like tomb now be a macabre tourist attraction, with visitors from across the world gawping up at it or pointing from boats and bridges or queueing to enter the monument to see the famous chain-suspended coffin? Would the tomb perhaps be a morbid counterpoint to sights such as the Statue of Liberty and Empire State Building, a garish though intriguing memorial not only to James Gordon Bennett Jr., but to an entire age of excess?

(This article’s main image – showing one of James Gordon Bennett Jr.’s glowing-eyed owls – is courtesy of nycscout.)

Well Done! Felt like i was privy to reading a new Dan Brown mystery! I think you are totally on to something here. I would say Alot went into this article! You have no idea how many twists and turns brought me to this article! A really well written, thought out, enjoyable read that kept me intrigued!! Loved the conspiracies, the architecture, Greek gods, times/places, the intrigue, humor, histories, and mysteries! Thank you for filling in soo many blanks! Alot of detective work went into this! ~Great Read~! 5*’s

Thanks, Dee, glad you enjoyed it.