Today Hampstead is one of London’s most exclusive districts. Home to politicians, rock stars, writers (more successful than this one), actors and TV personalities, Hampstead’s houses can go for well over £2 million. Beneath the quaint lanes of this village-like suburb, however, skulks a dark legend, a legend recalling an age of filth and disease, of dangerous and desperate labour, an age when London’s straggly outskirts and fetid byways still had some connection to a wilder, rural world. In the labyrinth of dark and stinking sewers under Hampstead was believed to live a colony of huge, mutant – and very vicious – feral pigs.

This legend maintained that a pregnant sow had somehow tumbled into a sewer and become lost in the maze-like world of London’s drains. After sustaining herself on the offal and rubbish that regularly washed through the system, the sow had given birth to her litter down there. According to one 19th-century account, her piglets soon grew up to ‘multiply exceedingly and become almost as ferocious as they are numerous’. Their inevitable inbreeding and strange light-starved environment apparently produced a race of monstrously large, black-furred hogs. These wild pigs were a terror to the ‘toshers’ – men who roamed the sewers hunting for coins, jewellery and other valuables that had slipped down drains to lie in the tunnels’ noxious silt. The toshers claimed the pigs hurtled out of the gloom to attack them if they got too close and that they had to keep a constant watch for the creatures if their subterranean wanderings took them anywhere near Hampstead. Some toshers even armed themselves in case they encountered the beasts.

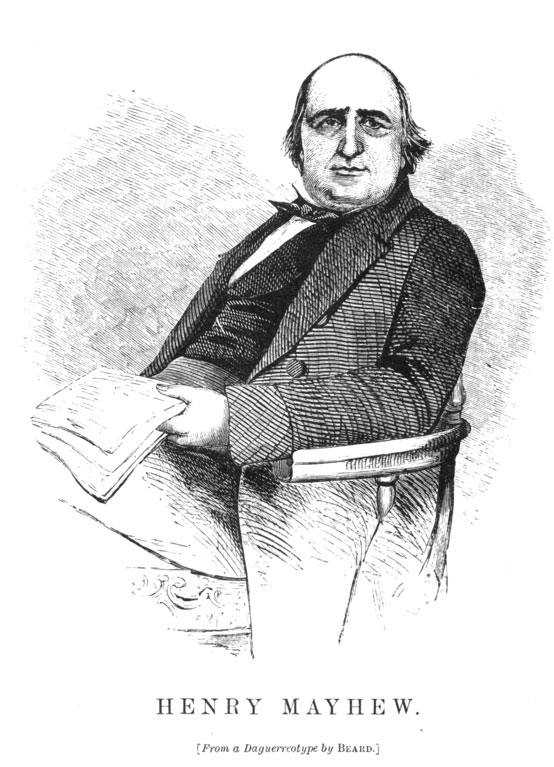

It seems the story of the Hampstead sewer pigs first grew up as a piece of occupational folklore among the toshers before being introduced to the general public courtesy of the journalist Henry Mayhew in his book series London Labour and the London Poor (1851), a vividly written, popular and highly influential work. The legend would also make it into the Daily Telegraph and even get a mention from Charles Dickens, all of which no doubt led many Londoners to shiver with the fear that there actually might be bands of ferocious pigs charging about just a few feet below them.

A quiet lane in Hampstead – did wild pigs once rove the sewers beneath it? (Photo: Nigeljbee)

But could there really have been a colony of feral boars roaming the sewers beneath Hampstead? Other than the toshers’ legends, what evidence was there for the existence of such creatures? What exactly did Mayhew say about the sewer pigs in his book? And what aspects of the toshers’ dark and dangerous lives in the thousands of narrow miles of London sewers might have triggered the rise of such a strange piece of folklore?

Continue reading for legends of a ‘Queen Rat’ who could transform herself into a stunning woman with an exceptional appetite for sex, of accounts of alligators swimming in the sewers of New York, and of rat swarms devouring toshers lost in lonely pipes. Also read on to learn how an infamous ‘Great Stink’ finally forced London to reorganise its sewer system – courtesy of the legendary Joseph Bazalgette – and how this rationalisation eventually helped drive some of the more outrageous myths from that subterranean world.

How the Legend of Hampstead’s Giant Sewer Pigs Was Born

A story recorded as early as 1736 has a pig fleeing a butcher’s knife and escaping into the sewers somewhere around Smithfield, a famous meat market on the edge of the old City of London. This plucky hog apparently spent five months roaming London’s sewers and feasting on their detritus before eventually emerging from the Fleet Ditch (the River Fleet, which had by that time become little more than an open sewer, a watercourse that, according to the poet Alexander Pope, ‘rolls the large tribute of dead dogs to Thames’).

The first published account of Hampstead’s subterranean pigs, however, comes from Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor. Mayhew had spent most of the 1840s scrutinising the lives of London’s more impoverished residents. He studied the work such people did, along with their domestic arrangements, sources of entertainment and religious beliefs, combining his own observations with official statistics. Among those he interviewed were food vendors, ‘bone grubbers’, ‘Hindoo tract sellers’, an eight-year-old girl who sold watercress, ‘pure finders’ (who hunted out dog dirt then sold it to tanners), rat catchers, prostitutes, sweatshop workers, and ‘sewer hunters’.

Did monstrous black pigs once haunt Hampstead’s sewers? (Photo: London Exposed)

The sewer hunters seem to have especially fascinated Mayhew. Also known as ‘toshers’ – after the ‘tosh’, meaning the scrap metal, nails, coins and bits of jewellery they sought out – these men walked London’s sewers with long-handled hoes. With these tools, they scoured the sediment on the pipes’ bottoms for such ‘treasures’. Mayhew wrote that until ‘some years ago, any person desirous of exploring the dark and uninviting recesses’ could get into London’s sewer system via the mouths of the huge pipes that gaped on the shore of the Thames and then simply ‘wander away, provided he could withstand the combination of villainous stenches that met him at every step, for many miles, in any direction.’ The toshers – their lanterns strapped to their chests – tended, however, to navigate this labyrinth in groups: due to fear of rat attacks. Through numerous conversations with the toshers, Mayhew came to piece together ‘a strange tale … of a wild race of hogs inhabiting the sewers near Hampstead’ which he described thus:

‘The story runs that, a sow in young, by some accident got down the sewer through an opening, and, wandering away from the spot, littered and reared her offspring in the drain: feeding on the offal and garbage washed into it continuously. Here, it is alleged, the breed multiplied exceedingly, and have become almost as ferocious as they are numerous. The story, apocryphal as it seems, nevertheless has its believers …’

A sceptic may, however, assert that – if a man could get into the sewers by simply walking into a pipe – surely the pigs could get out via the same method. According to Mayhew, though, the toshers ‘ingeniously argued, that the reason why none of the subterranean animals have been able to make their way to the light of day, is that they could only do so by reaching the mouth of the sewer at the riverside, while, in order to arrive at that point, they must necessarily encounter the Fleet Ditch (which was by then enclosed), which runs towards the river with great rapidity, and as it is the obstinate nature of a pig to swim against the stream, the wild hogs of the sewers invariably work their way back to their original quarters, and are thus never to be seen.’

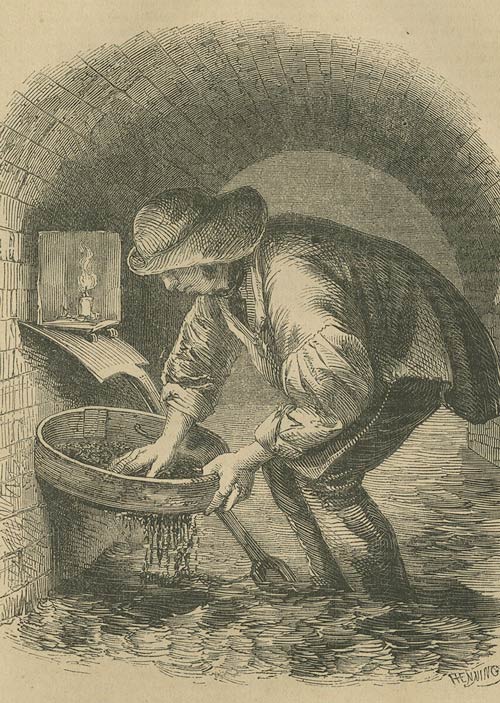

A tosher at work in the London sewer system

Though Mayhew wrote somewhat sceptically that ‘the reader of course can believe as much of the story as he pleases’, the tale of the wild pigs seems to have spread. Dickens referred to the legend and on 10th October 1859 an article mentioning Hampstead’s feral hogs appeared in the Daily Telegraph, by which time the story seemed to have acquired apocalyptic overtones:

‘This London is an amalgam of worlds within worlds, and the occurrences of every day convince us that there is not one of these worlds but has its special mysteries and generic crimes. Exaggeration and ridicule often attach to the vastness of London, and ignorance of its penetralia common to us who dwell therein. It has been said that beasts of chase still roam in the verdant fastness of Grosvenor Square, that there are undiscovered patches of primeval forest in Hyde Park and that Hampstead sewers shelter a monstrous breed of black swine, which have propagated and run wild among the slimy feculence, and whose ferocious snouts will one day uproot Highgate archway, while they make Holloway intolerable with their grunting.’

But could there have been any truth in the legends of the monstrous swine of Hampstead’s sewers? Could a pig have really got down there and started a hideous mutant breed or might the legend rather be some strange projection, some outlandish symbol of the daily sufferings of the capital’s toshers? Let’s plunge deeper into the dark waters of this very odd tale and attempt to find out.

Could There Have Been Any Truth in the Legends of Hampstead’s Huge Underground Pigs and What in the Toshers’ Lives Might Have Led to Myths of Such Monsters?

Theoretically, it could be possible that domestic animals ended up falling into sewers. London was full of livestock at that time – wandering pigs, cattle being driven to market – and many ditches and sewers were wide open or at least easy to enter. Whether any of these beasts would have managed to survive down there, completely failed to get out and succeeded in breeding a tribe of descendants is, however, more questionable. Henry Mayhew was, despite the protests of those he interviewed, dubious about the existence of such creatures, noting, ‘What seems strange in the matter is, that the inhabitants of Hampstead never have been known to see any of these animals pass beneath the gratings, nor to have been disturbed by their gruntings … it is also right to inform (the reader) that the sewer hunters themselves have never yet encountered … the monsters of the Hampstead sewers.’

Henry Mayhew – author of London Labour and the London Poor – wrote the first known accounts of the monstrous pigs of Hampstead’s sewers.

So, while it’s not impossible that a colony of pigs might have bred in the London sewer system, we should perhaps lean towards the sceptical in this matter and look for other explanations as to why this outlandish legend might have grown up. Perhaps we could see the sewer-dwelling hogs as a kind of symbol – in fleshy ferocious form – of the dangers and discomforts the toshers faced.

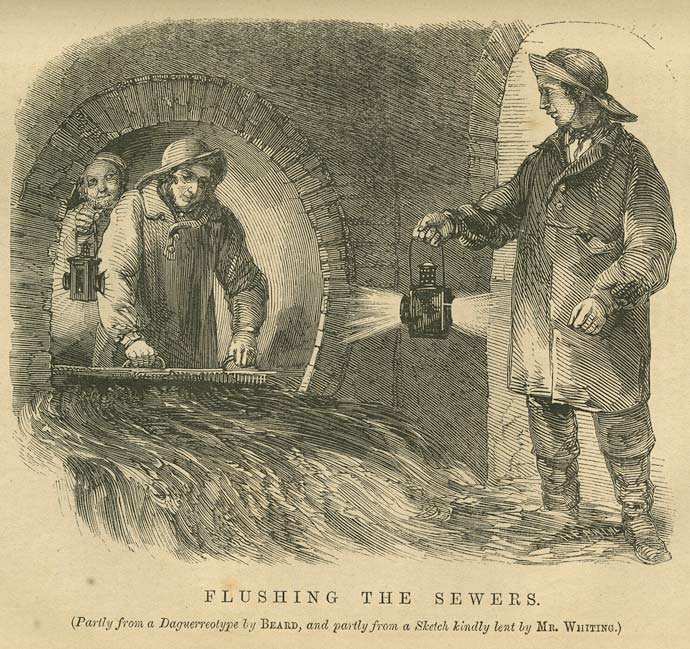

Their job was certainly perilous. London’s sewers – built over centuries without much planning – sprawled for thousands of sludgy miles. Perhaps a thousand miles of these narrow passages would have been navigable to humans though – Mayhew noted – they averaged a height of just three-feet-nine-inches. The toshers faced threats such as cave-ins, getting hopelessly lost in the endless warren, and stagnant fumes, not to mention rat attacks and the danger of being drowned when the tide came creeping up the Thames and into the tunnels. The tide filled the sewers to their ceilings twice daily. But, in addition to this, some sluices were raised at low tide, releasing tsunamis of sewage that could drown or even pulverise the incautious. Explosive gases, such as sulphate hydrogen, could lurk in the passageways while another hazard was falling bricks. ‘The bricks of the Mayfair sewer,’ the biographer of London, Peter Ackroyd, writes, ‘were said to be as rotten as gingerbread, you could have scooped them out with a spoon.’

To make matters worse, in 1840, the work of the toshers was declared illegal. Nobody was allowed to enter London’s sewer network without permission and a £5.00 reward was available to those informing on anyone doing so. This added to the dangers toshers faced as it meant they had to do most do their work at night, relying solely on lanterns, deprived of even the light that filtered down through gratings or shone from tunnel mouths. ‘They won’t let us work … as there’s a little danger,’ one sewer hunter complained. ‘They fears as how we’ll get suffocated, but they don’t care if we get starved!’

Flushing London’s sewers – sluices could sometimes release water, drowning unwary toshers.

Mayhew described the sewer hunters thus: ‘(They) may be seen, especially on the Surrey side of the Thames, habited in long greasy velveteen cloaks, furnished with pockets of vast capacity, and their nether limbs encased in dirty canvas trousers, and any old slops of shoes … (They) provide themselves, in addition, with a canvas apron, which they tie round them, and a dark lantern similar to a policeman’s: this they strap before them on the right breast, in such a manner that on removing the shade, the bull’s eye throws the light straightforward when they are in an erect position … but when they stoop it throws the light directly under them so that they can distinctly see any object at their feet. They carry a bag on their back, and in their left hand a pole about seven or eight feet long, on one end of which there is a large iron hoe.’

This hoe was an essential part of the tosher’s kit. As well as being used to rake through the sewer’s muck in search of valuables, this implement could save lives. Mayhew stressed that ‘should they, as often happens even to the most experienced, sink in some quagmire, they immediately throw out the long pole armed with the hoe, and with it seizing hold of any object within reach, are thereby enabled to draw themselves out.’

A group of toshers photographed in London’s sewers in the late 19th century – unlike earlier illegal toshers, these men were employed by the city

Though the tosher’s job was a dangerous one, it did have some rewards. Most toshers worked in gangs of three or four, led by an experienced man who could be between 60 and 80-years-old. These veterans knew where hidden cracks were located, cracks in which coins were frequently found lodged. Mayhew wrote of men who’d ‘dive their arm down to the elbow in mud and filth and bring up shillings, sixpences, half-crowns, and occasionally half-sovereigns and sovereigns. They always find these coins standing edge-uppermost between the bricks in the bottom, where the mortar has been worn away.’

The sewers could indeed harbour riches and it’s estimated that they supported a workforce of around 200 scavengers, many of whom went by nicknames, such as Lanky Bill, One-eyed George and Short-armed Jack. Mayhew found they could earn as much as six shillings a day ( about £36 in modern money), which – while it might not sound much – would have placed them in the upper income bracket of the working class at the time. Mayhew, with some astonishment, noted, ‘At this rate, the property recovered from the sewers of London would have amounted to no less than £20,000 (about £2.38 million today) per annum.’

Despite its many hazards, the sewer hunters didn’t necessarily view their work as unhealthy. Mayhew noted the men were fit, strong and even ruddy in skin tone. They often enjoyed remarkable longevity. Some even felt the stinking air of the tunnels ‘contributes in a variety of ways to their general health.’ Mayhew suspected that – if they were to become ill – it was more likely to be the fault of the fetid slums they lived in. The journalist described one narrow court south of the Thames as containing around 30 houses, each with no less than eight rooms, with each room stuffed with nine or 10 inhabitants.

Around the time Mayhew was making his records, though, life in the sewers was worsening. In addition to the new law forcing toshers to work at night, the tunnels in which they laboured were becoming filthier. Until the early 1800s, sewers transported little more than rainwater, with toilets discharging into cesspits rather than the sewer network. A law of 1847, however, closed all cesspits and ordered that latrines should empty directly into sewers, resulting in the tunnels building up linings of excrement. By the end of the decade, the Thames they all flowed into was biologically dead.

According to Michelle Allen – author of Cleansing the City: Sanitary Geographies in Victorian London – by the mid-19th century London’s sewers were ‘volcanos of filth, gorged veins of putridity, ready to explode at any moment in a whirlwind of foul gas, and poison all those who they failed to smother.’ Mayhew noted that the ‘deposit’ found in London’s sewers ‘has been found to comprise all the ingredients from the gas works, and several chemical and mineral manufacturies; dead dogs, cats, kittens and rats; offal from slaughter houses, sometimes even including the entrails of animals; street pavement dirt of every variety; vegetable refuse, stable dung; the refuse of pig styes; night soil; ashes; rotten mortar and rubbish of different kinds.’

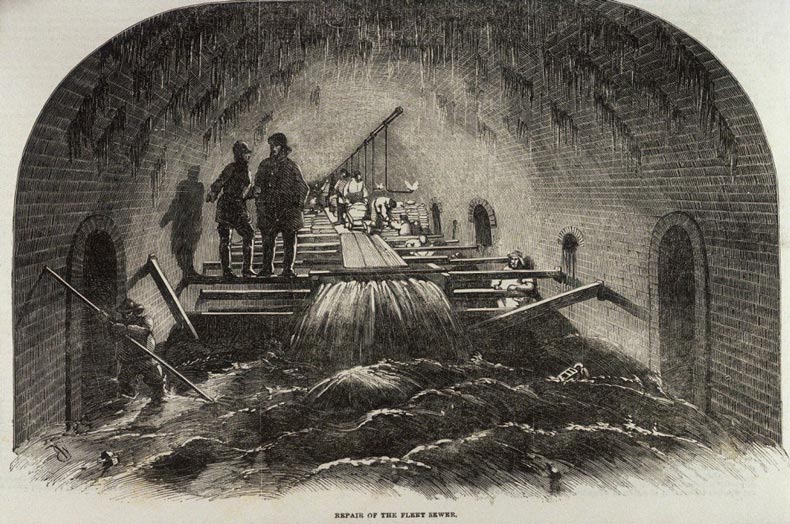

The Fleet runs through a London sewer – apparently the river’s force prevented Hampstead’s sewer pigs from escaping the network.

Despite all this, the toshers seem to have considered animal – specifically rat – attacks and bites as the greatest danger of their trade. (Though it’s likely that more rats would have entered the sewers and the rat colonies down there would have expanded thanks to the increasing levels of waste London’s subterranean pipes were struggling to deal with.) Mayhew interviewed one Jack Black – ‘Rat and Mole Destroyer to Her Majesty’ – who told him, ‘When a bite is a bad one … it festers and forms a hard core in the ulcer, which throbs very much indeed. This core is as big as a boiled fish’s eye, and as hard as stone. I generally cuts the bite out clean with a lancet and squeezes … I’ve been bitten nearly everywhere, even where I can’t name to you, sir.’

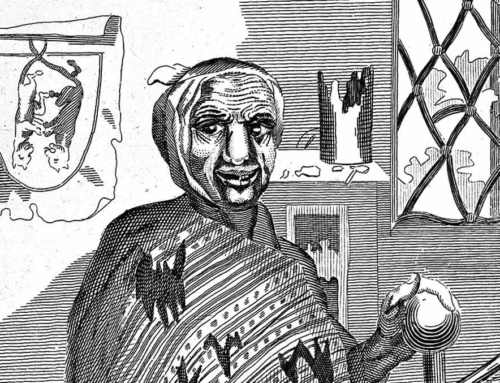

The rat catcher Jack Black, depicted in Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor

Mayhew stated he’d heard many stories of mass rat attacks on toshers, with the desperate men ‘slaying thousands in their struggle for life’. The rats didn’t dare attack toshers in a group, but if a pack of the creatures assailed a single man, he had little hope. The tosher would fight bravely, swinging at and batting the animals with his hoe until ‘at last the swarms of the savage things overpowered him’. The unfortunate tosher would likely be ripped to pieces, pieces that would drift with the rest of the sewage towards the Thames. His fellow toshers might discover some of his remains a few days later ‘picked to the very bones’.

It’s perhaps not surprising that the worsening state of the sewers and the existence of – real life – monstrous animals in them led to tales of ferocious beasts of a more mythical nature, such as Hampstead’s subterranean pigs. Hazardous working conditions can produce legends of weird beings. In mining folklore, there were creatures called ‘knockers’ – leprechaun-like characters, often clothed in miniature miners’ garb – who created the ‘knocking’ sound miners heard just before cave-ins. Some miners saw knockers as malevolent spirits who tried to cause collapses by hammering away at supports while others viewed them as kindly sprites who knocked to warn miners of approaching disaster. In the US steel industry, there emerged a character called Joe Magarac – a superhuman labourer made entirely of steel who drank molten metal, moulded steel with his bare hands, and saved workers from accidents. In Glasgow, a legend of an iron-fanged, child-eating vampire grew up around an iron works, a foundry which blighted its poverty-plagued neighbourhood with air, noise and light pollution.

Jacqueline Simpson and Jennifer Westwood – in their Lore of the Land: A Guide to England’s Legends – mention another mythical creature known to the toshers: one ‘Queen Rat’. This rat followed groups of toshers through the sewers and – when she saw one she liked the look of – she would transform into a beautiful and seductive woman. Despite her beauty, however, her eyes – like a rodent’s – still reflected light and she had claws on her toes. If the tosher ‘gave her a night to remember’, Queen Rat would grant him luck, making sure he found lots of coins and precious items. If, however, the tosher was brash enough to boast of his exploits to his friends or if he clumsily offended the rodent queen, his luck would abruptly change and he’d drown or suffer a terrible mishap.

A legend handed down in a London family claims that in around 1890 a tosher called Jerry Sweetly met Queen Rat in a public house. Jerry took the girl to a dance, after which she ‘led him to a rag warehouse to make love’. As the two frolicked, Queen Rat bit Jerry on the neck, which she commonly did to mark her lovers so no other rats would hurt them. This, however, surprised Sweetly, causing him to lash out, at which Queen Rat sprang into the warehouse’s rafters. From there, she shouted, ‘You’ll get your luck, tosher, but you haven’t done paying me for it yet.’ Sweetly’s first wife died while giving birth and his second spouse was killed on the Thames, crushed between a barge and wharf. But good luck favoured all his children and – each generation – a girl is born into the Sweetly family with contrasting eyes: one blue, the other the grey colour of the Thames.

Could it be that the giant sewer-dwelling pigs of Hampstead and the tales of Queen Rat were legends invented by the toshers to express in mythical form their grim working conditions and the dangers they faced, both general hazards and those specifically associated with animal attacks? This to me seems a likely explanation, but what we must now ask is what happened to this strange folklore and what made it die out?

‘The Great Stink’ – Joseph Bazalgette’s Improvements Rationalise London’s Sewers and Challenge the Legend of Hampstead’s Underground Pigs

By the middle of the 19th century, it was clear that the way London dealt with its human waste needed to be overhauled. While there was an extensive sewer network, it was piecemeal, uncoordinated and frequently burdened beyond its capacity to cope, mainly due to a mushrooming population that had increased from one to three million in the first half of the 1800s. Mayhew wrote that during spring tides, effluence ‘burst up through the gratings and into the streets’ until the districts close to the Thames ‘resembled a Dutch town, intersected by a series of muddy canals.’ Almost all the filth of London did, eventually, however, end up in the Thames, with the introduction of the flushing toilet making matters much worse as it allowed wealthier inhabitants to channel their waste straight into the river.

The scientist Michael Faraday described how ‘near the bridges, the feculence rolled up in clouds so dense they were visible at the surface’ while Charles Dickens complained the Thames was ‘a deadly sewer … I can certify that the offensive smells, even in a short whiff, have been of a most head and stomach distending nature.’ The Thames was also the source of much of the capital’s water for drinking and washing and – unsurprisingly – several cholera epidemics ravaged London. The Metropolitan Board of Works had wanted to improve the city’s system of sewer disposal for years but had never had enough money.

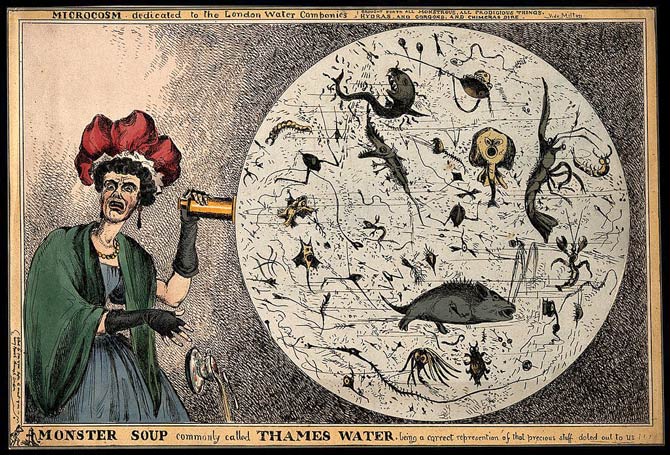

Monster Soup – Commonly Called Thames Water, by William Heath, 1828. A woman drops her teacup in horror after a microscope reveals her drink’s impurity.

Things changed, however, in the summer of 1858 – when London endured an episode known as ‘the Great Stink’. A spell of freakishly hot weather exposed just how much human effluent, industrial waste and other pollutants the Thames was carrying and resulted in the most unbearable stench rising from the river. The stink overwhelmed all neighbourhoods close to the Thames, Westminster included.

The curtains of the Houses of Parliament were soaked in chloride of lime in a futile effort to rebuff the pong and there were discussions about moving the government to St Albans or Oxford. The prime minister Benjamin Disraeli was reported as fleeing from a committee room, ‘with a mass of papers in one hand and his pocket handkerchief applied to his nose’ and during a debate he referred to the Thames as ‘a Stygian pool, reeking with ineffable and intolerable horrors’. The press too complained long and loud about the state of the river and newspapers filled up with garish cartoons highlighting just how disgusting the Thames was. The City Press observed that ‘it stinks, and whoso inhales the stink can never forget it and can count himself lucky if he lives to remember it’ while The Standard described the watercourse as a ‘pestiferous and typhus breeding abomination.’ Queen Victoria and Prince Albert did attempt to take a pleasure cruise on London’s river, but the foul stench soon drove them ashore.

The ‘Silent Highwayman’. Death rows on the Thames, claiming the lives of those who won’t pay to have the river cleaned up. From Punch magazine, 1858

Perhaps because the river’s problems – rather than just slaying the poor and middle class with recurrent epidemics of cholera and typhoid – had now reached right into the home of power and assailed the very nostrils of the monarchy, action was swiftly taken. A bill was rushed through Parliament, becoming law in just 18 days. The bill provided money for a massive new sewer scheme, with The Times commenting that MPs had been ‘forced by sheer stench’ to tackle the issue.

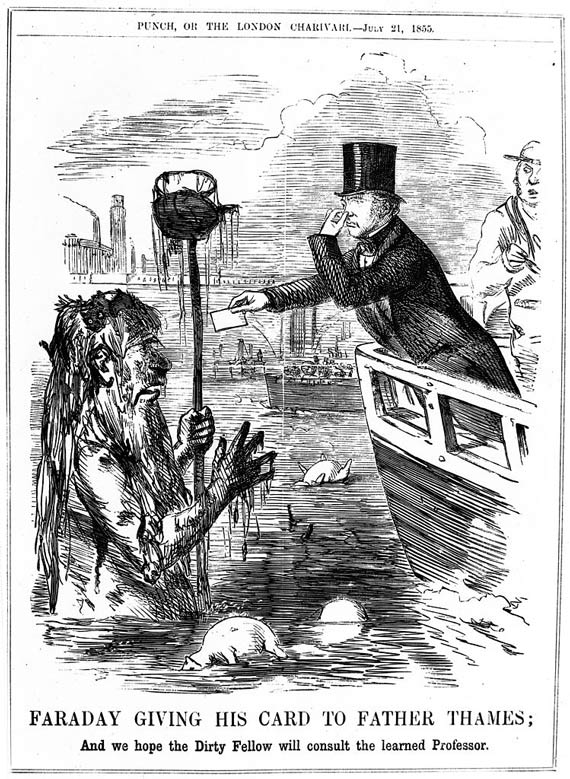

A filthy Father Thames meets the scientist Michael Faraday. Faraday performed an experiment in which he dipped a piece of white paper in the river to test its opacity.

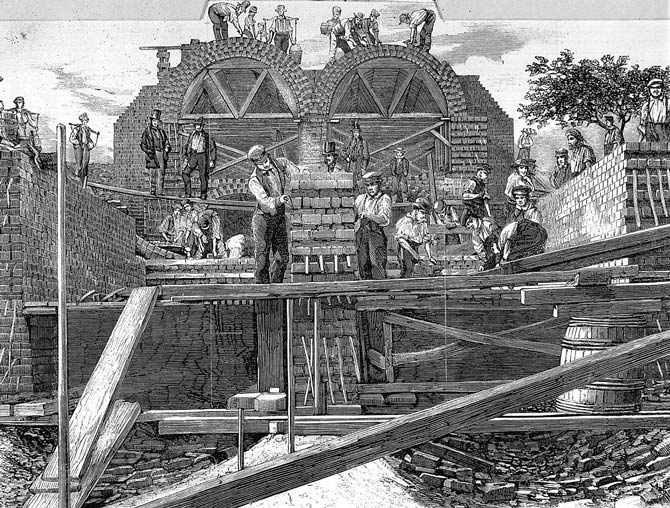

Joseph Bazalgette – the chief engineer of the Metropolitan Board of Works – was hired to design this new system, a network projected to cost the massive sum of £2.5 million (over £317 million in modern money). Bazalgette connected up the existing labyrinths of municipal drains and built 1,100 miles of new drains under London’s streets. All these drains, in turn, fed into 82 miles of brick-lined sewers, which themselves flowed into six large ‘interceptor sewers’, some of which were built around London’s ‘lost’ buried rivers, like the River Fleet. The interceptors discharged into two even more enormous tunnels that ran along the north and south banks of the Thames. Aided by pumping stations at Deptford and Abbey Mills – which used the biggest steam engines then operating in the world – these tunnels shifted all of London’s effluent eight miles downstream to be dumped in the Thames Estuary.

Bazalgette’s gargantuan project devoured 318 million bricks and 670,000 cubic metres of concrete. Thousands of labourers were employed to dig the new tunnels while the demand for bricklayers drove the wages of those craftsmen up by 20%. Though the construction of his system wasn’t without its problems, many of Bazalgette’s sewers still serve London to this day and his designs have very much marked the face of the city. His huge riverside tunnels are buried under elaborate embankments – among them the Victoria, Chelsea and Albert Embankment – the construction of which narrowed the Thames by 22 metres. Bazalgette’s project was not completed until 1875, by which time the sewer system could carry two billion litres of wastewater every day.

A sewer being constructed as part of Bazalgette’s project in Bow, East London, 1859

We might ask what all this has to do with colonies of feral pigs living underneath Hampstead. It appears – as Bazalgette’s scheme involved so much surveying and reconstruction and the pouring of so many labourers and engineers down into London’s underworld – that the whole sewer network became far less of a enigma. Bazalgette himself insisted on inspecting every interchange between the old drains and new sewers and signing off every single plan that was part of his grand project. As there were absolutely no reports of any workmen or contractors encountering the supposedly large hoards of terrifying swine, the legend seems to have been discredited before fading from memory. But even the most rationally organised sewers will still have a certain mystery about them, will always represent a sort of urban Hades, a dark and claustrophobic netherworld, a collective unconscious of the city where strange, semi-mythical beings still might lurk, as we’ll find out in the next section.

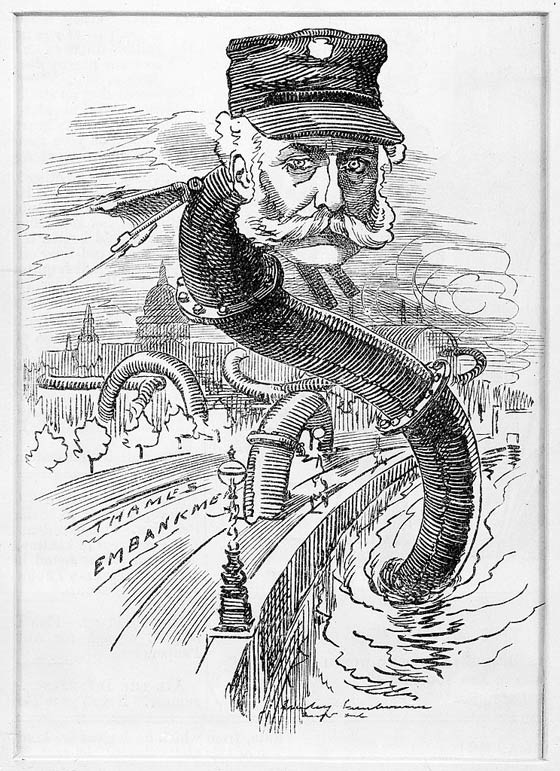

Joseph Bazalgette depicted as a London sewer snake, in Punch magazine, 1883

Alligators in the Sewers of New York, Subterranean Cows and How ‘Improvements’ Might Sometimes Create Their Own Monsters

In addition to Hampstead’s wild pigs and the folklore of Queen Rat, there are other strange tales of underground animals. One of the most notorious legends of subterranean creatures comes from New York. On February 9th 1935, New York’s newspapers were abuzz with the news that an alligator had been found in an uptown sewer. Some East Harlem teenagers had been shovelling snow down a drain when one of them had noticed movement. Peering into the hole, he’d been shocked to realise he was looking at an alligator. The youths lassoed the animal with a clothesline, dragged it up into the street, and – when it snapped at them – they beat it to death with their shovels. The beast’s corpse weighed 125 pounds and boasted a length of seven-to-eight feet.

Could this report have been true? Though newspapers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were often full of what we’d today call ‘fake news’ – ranging from ‘unlucky mummies’ to man-eating plants – there are other accounts of alligators cropping up in New York. In 1932, two alligators – one almost three feet long – were discovered near the Bronx River in Westchester while in 1937 a barge captain lassoed a nearly five-foot, one-hundred-pound creature off Pier Nine in the East River. ‘Well, I can’t throw it back where the boys go swimming,’ the captain said, when the police declined to take the alligator off his hands. ‘I guess I got myself a pet.’ Just six days later, a two-foot alligator was spotted crawling along a Brooklyn subway platform and was caught by the police.

The New York sewer alligators are likely to have been discarded pets. Baby alligators were once quite a craze, with one ad in a boys’ magazine stating: ‘Do you want a baby alligator? You bet you do. What boy wouldn’t?’ These alligators, the ad promised, could be sent through the post at a total charge of $1.50. Newspaper reports gave details of postal clerks sometimes struggling with such creatures that had escaped their packages. The alligators, of course, didn’t stay babies for long, no doubt leading to some being slipped down the drain. Though it seems there was some truth in the tales of alligators swimming in New York’s chilly waters and crawling in the city’s sewer pipes, it’s likely the extent of the issue was exaggerated by the media and a panicking public, resulting in scare stories somewhat similar to those of Hampstead’s subterranean swine.

An alligator is captured in New York’s East River

Cows were also once believed to run beneath New York streets – in special tunnels constructed at the end of the 19th-century to relieve ‘cow jams’ in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District. Such tunnels were rumoured to have existed beneath Twelfth Avenue, under Greenwich, Renwick or Harrison Street, and under Gansevoort Street in the West Village. Some say the tunnels are oak-lined, others that they’re lined with field stones or made of steel. Some claim these bovine corridors were demolished to make way for gas mains; others assert they still lie beneath New York in a perfect state of preservation. The Edible Geography website sees this legend as something of an eruption of the countryside into the heart of the new urban environment: ‘What’s amazing about these elusive cow tunnels is that, whether or not they actually exist, they form a shared urban fantasy – a mythical meat-processing infrastructure haunting contemporary New York.’

Edible Geography also delves into the folklore of Hampstead’s sewer pigs, pointing out that – in the mid-1800s – when the legend of Hampstead’s underground swine was at its most vigorous, Hampstead was a semi-rural farming village on the outskirts of London. At the time, however, London’s relationship with its rural surroundings was changing due to factors such as the advent of railways and factories, the Metropolis’s ever-expanding growth, and migration from the countryside to the city. Might Hampstead’s legends of sewer pigs then, like New York’s cow tunnels, have perhaps been a reaction against these upheavals, a way to remember the rural in an environment that was rapidly urbanising? Might the pigs have been a relatively short-lived, transitional myth that was doomed to be swept away by even greater progress – the building of Bazalgette’s sewer system? In 1859, the writer Richard Rowe complained of how such ‘improvements’ had blighted the landscape, lamenting how sewers and railways had ‘played sad havoc with the country around London’, scarring it with ‘cannon-like drained pipes’ that ‘crash the nettles in the ditches’ and ‘raw red entrances’ to tunnels that resembled wounds. It might also be said, however, that the Hampstead and Highgate area does seem to be home to a lot of odd myths – from haunted old pubs, to a vampire said to have skulked in Highgate Cemetery, to the ghost of a semi-plucked chicken that the 17th-century philosopher Francis Bacon had tried to preserve by stuffing with snow.

Whatever the cause of the strange legend of Hampstead’s underground pigs, it is perhaps a story that can be seen as mapping London’s rapid and traumatic development, a story which draws from the danger, tough working conditions, wealth, poverty, sickness, filth, progress, hope and myth that have clustered around the growth of one of the world’s darkest and most influential cities.

(This article’s main image is courtesy of Thought Catalogue)

Fascinating post. I love the investigative style of your writing. I initially thought the pigs may have been created as a warning to keep other folk away from the sewers so the toshers could have the “finds” to themselves but I think the transition from rural to urban theory is also applicable

Interesting idea – that the myth was invented by the toshers to keep people away. I hadn’t thought of that.