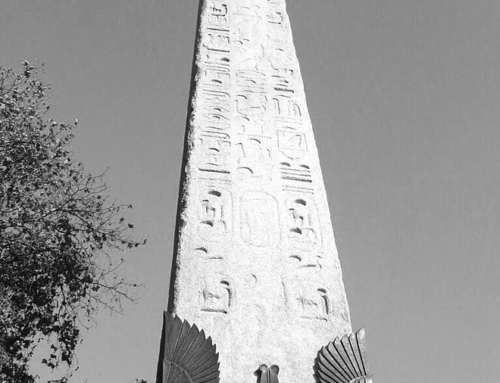

Père Lachaise Cemetery is the largest necropolis in Paris and the world’s most visited graveyard. This elegant city of the departed contains over one million interments and undulates across 44 tree-scattered hectares. It’s famous for its striking neo-classical and neo-gothic tombs and its many well-known tenants, ranging from actors and writers to politicians and rock stars. But a certain mausoleum seems to puncture Père Lachaise’s atmosphere of stylish melancholy. In Division 19 of the cemetery, a marble tomb looms on a hill, towering at an imposing 32 feet (10 metres). This massive mausoleum is covered with strange symbols and weird gargoyles and adorned with numbers said to harbour an occult significance. Visitors who’ve lingered near the tomb have reported feelings of desolation and emptiness. Some have sensed a disturbing presence or even intuited that something is sucking at their energy.

The mausoleum – resembling a hulking Greek temple and surrounded by pillars capped with the memento mori emblems of eternal flames – is the resting place of the Russian aristocrat Baroness Elizaveta Demidoff. Elizaveta (Elizabeth) died on 8th April 1818 and was buried in Père Lachaise the next day. Though in life Baroness Demidoff was famed for her beauty and light-hearted humour, a sinister legend would grow up around her tomb. Elizaveta is said to lie in a glass coffin, but the legend goes well beyond this Snow-White-like detail. What’s really creepy is the claim that a very odd clause lurks in Baroness Demidoff’s will.

Baroness Demidoff’s tomb looms over the other graves in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris. (Photo: Luca Borghi)

The will is said to promise a fortune – one million francs, some maintain; others assert as many as five million, equivalent at the time to about a million dollars – to any person brave enough to endure an especially gruesome ordeal. To earn this money, the person would have to spend 365 days and 366 nights alone with Baroness Demidoff in her tomb. Any such candidate would be forbidden all human contact for the duration of the trial. And – just to make the experience even grimmer – the tomb’s walls and ceilings are rumoured to be lined with mirrors. Wherever the contender looked, the sight of the baroness’s body in her crystal casket would assail them.

The legends claim several courageous, or at least greedy, individuals have taken up the challenge. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the same legends state none were able to see it through. After – in most cases – just a few days, contenders were pummelling the tomb door, begging to be let out. Some suffered mental breakdowns or heart attacks; others swore they’d felt a vampire-like entity draining their lifeforce.

But who exactly was Baroness Elizaveta Demidoff and how did these outlandish stories become attached to her? Did her will really lay down such a macabre challenge? What might the strange symbols and occult numbers carved on her tomb mean and why do some people associate them with the vampiric? Let’s investigate below.

The Colourful Life and Early Death of Baroness Demidoff

Baroness Elizaveta Alexandrovna Stroganova entered the world on 5th February 1779 in St Petersburg, Russia. She was born into one of the nation’s wealthiest families, a family that had risen from peasant origins to become landowners, traders and industrialists, making much of their money from salt and fur. This increase in social status was further boosted when Tsar Peter the Great (reigned 1682-1725) bestowed on them the title of Barons of the Russian Empire.

Elizaveta acquired a reputation as a beautiful and beguilingly light-hearted young woman. A number of portraits were made of her, which collectors still prize. At 16-years-old, she married Nikolay Nikitich Demidoff. Nikolay, born in 1773, was from an extremely rich family of industrialists that had acquired their cash from copper, silver and gold mines and iron foundries. He became a diplomat and the couple were posted to Paris.

Portrait of Baroness Demidoff as a child

They both enjoyed life in the city, but Paris especially suited Elizaveta’s outgoing lively nature. Nikolay, in contrast, was more reserved and focused much of his attention on increasing his family’s fortune, obsessing over how to modernise their industrial operations. The Demidoffs had four children, with two – Pavel and Anatoly – surviving to adulthood. Anatoly was destined to continue the family’s social rise – he’d have the title of Prince of San Donato bestowed on him by the Italian government and would marry Napoleon’s niece Mathilda.

During their years in Paris, Nikolay and Elizaveta became admirers of Napoleon Bonaparte, but in 1805 increasing tensions between Napoleon’s regime and Russia led to Nikolay being redeployed. The family spent some years in Italy before the Tsar recalled them to Russia in 1812. Nikolay and Elizaveta settled in Moscow, but – due to the differences in their personalities – they separated shortly after their return. Nikolay remained in the Tsar’s service and would fight against Napoleon in spite of the esteem in which he held the French Emperor. He’d later gain the post of Russian ambassador to the Court of Tuscany. In 1827, Grand Duke Leopold II granted Nikolay the title of Count of San Donato – a mark of gratitude for Nikolay’s role in establishing a silk factory there.

Portrait of Baroness Demidoff – a woman famed for her beauty and lively character

After separating from her husband, Baroness Demidoff moved back to her beloved Paris, but she died there in 1818 at the age of just 39. She was buried in the newly fashionable Père Lachaise Cemetery, which had only opened in 1804 to relieve pressure on overcrowded Paris churchyards. Elizaveta’s mausoleum was originally located in Division 39 of the vast necropolis, but was later moved to the 19th.

Elizaveta’s husband Nikolay Demidoff

So Elizaveta appears to have led a privileged, often enjoyable, but in many ways unremarkable life for a woman of her time and social position. She’s known to have died wealthy, but gossip claimed she was perhaps a little nutty towards the end. Her real fame, however, came after she passed away, thanks to the lurid rumours that circulated about her last will and testament, rumours that would make it into both the French and international newspapers.

The Strange Will of Baroness Demidoff, the Macabre Challenge to Spend a Year in Her Tomb and the ‘Vampiric Symbols’ on Her Mausoleum

Most of what we know about the strange and morbid will of Baroness Demidoff comes from articles in the 19th century press. These articles – some of which refer to the Baroness as a ‘countess’ or even a ‘princess’ – outlined how those taking up her challenge had to follow certain rules. The will, we are told, forbade ‘all visitors. The candidate must be alone with the dead for a whole year before the whole $1,000,000 is won.’ Though a servant would bring ‘meals regularly to the watcher’ and would carry away the bucket containing their bodily waste, any attempts to communicate with this employee were strictly forbidden. The contender was allowed to leave their gloomy lodgings once a day ‘to stroll among the tombs for an hour’. But – to make sure no human contact could be achieved – this walk had to be undertaken after the necropolis’s gates had closed for the night or before they opened in the morning.

The newspaper reports emphasised the horror of passing so much time in such proximity to the corpse of Baroness Demidoff. ‘The princess lies in a crystal coffin,’ one article stated, ‘Thus, the whole body is distinctly visible, and this is what causes so much fright to all who have as yet attempted to gain the prize.’ Another journalist described how ‘the body of the princess, according to legendary report, lies in a crystal coffin, in a wonderful state of preservation’, stressing that ‘in order that the man or woman who might undertake the long watch should never lose sight of it, and during the whole year and a day have his thoughts constantly occupied with the deceased princess, the walls and ceiling were lined with plate-glass mirrors, so that, whichever way the watcher might turn, he or she would always be confronted by the spectacle of the dead Princess in her glass coffin.’

How, then, might the watcher have achieved any respite from this grisly display? Though contenders were forbidden to distract themselves with any sort of work, books and newspapers were permitted. Such material could be read by ‘the funeral light at the head of the coffin’. But what would happen to the candidate if, in a moment of weakness, they attempted to talk to the meal-bearing servant or sneak over the cemetery walls? We’re told that ‘in the case of any of these stipulations being violated, the watch was to recommence, or all hope of inheriting the million francs be abandoned.’

Baroness Demidoff’s mausoleum in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris. (Photo: The Paranormal Guide)

Despite these rigorous demands, there was no shortage of applicants willing to go through the ordeal. An article in a Chicago newspaper stated, ‘Several Frenchmen have essayed to win the prize, but all have given up after a short trial. One lasted out nearly three weeks, by which time he had completely lost his reason and still remains a jabbering idiot. The will makes no mention of foreigners being ineligible; there is every chance, therefore, for a strong-minded American who fears neither ghosts, ghouls nor gravestones to become rich in the short period of 365 days. Applications to be made to the municipality of Paris.’

Letters indeed flooded in from across the world. ‘Though applications to watch by the coffin of the Russian Princess came from all parts of Europe, and even North and South America,’ one article related, ‘Belgium seems to have furnished the largest number of intrepid individuals willing and anxious to sit for a whole year beside the glass coffin.’ Would-be contenders included ‘an old soldier, occupying the post of night watcher in a factory’ who ‘declared he would certainly earn the million francs if the conservator of the cemetery would only admit him into the tomb of the Princess’ and ‘a young shepherd of Laekesles-Bruxelles’. This young man ‘was in such a hurry to commence the watch that would make him rich and enable him to marry the girl he loved, that he begged the conservator of Père Lachaise to indicate the day and hour at which he might present himself.’ A letter from an American, which still exists, earnestly requests ‘please tell me if this is a bona fide offer’ before adding ‘if it is, please consider me an applicant of these requirements at once’ then signing off ‘And greatly obliged – yours very truly, J.H. Davis.’

It wasn’t only men who were prepared to endure a gloomy year in the presence of Baroness Demidoff’s remains. An article expressed surprise at ‘the number of widows who presented themselves for the interminable watch … they disguised their desire to become rich with the supposed Princess’s million francs under all sorts of excuses. They wanted the money for this and that praiseworthy object – to help a friend, to provide for a daughter etc., and one even went so far to declare that if she earned the money she would found a home for orphans.’

Even newspaper reporters themselves, including those working for respectable journals, seem to have been seduced by the prospect of the Baroness’s fortune. One article related how ‘a journalist on Le Temps seriously enquired with whom the money had been lodged, and whether he was quite sure to receive the million if he succeeded in accomplishing the watch.’

The parade of people presenting themselves to undertake the ordeal grew as the story of Baroness Demidoff’s will spread. One American newspaper described how applicants ‘began to bombard the officials in Paris and our ambassador with letters seeking information and so numerous were these enquiries that the prefect of police had to hire another clerk, the city fathers had to increase their secretaries, and Mr Eustice had to call in the extra hall man at the embassy to open the communications that arrived from all parts of North America.’ Some would-be contenders tried to bribe officials with presents or with cuts of the prize money.

Most who attempted the challenge, however, are said not to have lasted long before screaming to be let out. Tortured by the inescapable presence of the Baroness’s corpse – and haunted by its incessant reflection in the mirrors all around them – few endured for more than a fortnight. One man is alleged to have gone totally insane, another to have died of a heart attack soon after his release. Others felt their vitality being drained, with one sensing his very life was seeping from him. Some contenders claimed to have ‘heard unearthly and mysterious sounds’ or to have ‘been struck with horror and fear by ghostly apparitions’. Certain candidates suspected the tomb was a portal leading to hell while others came out covered in scratches and bruises. Even present-day visitors to Père Lachaise have reported feelings of unease and emptiness around the mausoleum and strong urges not to linger nearby. It’s been theorised that Baroness Demidoff may be some sort of ‘energy vampire’, with the challenge in her will a means of providing her with victims so she could feed off their lifeforce.

The strange design of the Baroness’s tomb has also stimulated ideas about her ‘vampirism’. The mausoleum boasts carvings of bats and of wolves’ heads, with the wolves rumoured to guard the Baroness’s body during the daytime. The tomb also bears a carving of a knot – thought to depict the Knot of Hercules, which symbolises the binding together of the states of life and death. The date of Baroness Demidoff’s demise is also believed to be significant. She died on April 8th, 1818, and the number eight – with its interconnected loops – is said to be an emblem of infinity when laid on its side. Or it could represent the eternal ouroboros – the cosmic snake biting its own tail. It’s claimed three eights are to vampires what three sixes are to the Devil or that eight is a number of occult initiation, with nine being the number of the accomplished adept.

A wolf’s head on Baroness Demidoff’s tomb in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris – a daytime guardian of the vampire princess?

There’s also the tomb’s location within Père Lachaise Cemetery. It sits on the Alley of Acacias. The acacia plant is a symbol of resurrection, immortality and initiation, frequently found in Freemasonry. The Baroness’s tomb also lies on the Path of the Dragon – the name Dracula stems from the word meaning ‘dragon’ or ‘devil’ in the Romanian language. Baroness Demidoff’s body is said to face the setting sun, which also has – apparently – some vampiric significance, and it’s alleged her corpse doesn’t show any signs of decomposition. In modern times, there are those who have attempted to film inside the tomb – through a cross-like opening in its door – and who claim to have captured the eerie movements of some florescent figure or a glowing demonic face.

There’s no doubt that the newspaper reports about Baroness Demidoff appeared and that people did send letters asking to take up her challenge. But how much truth actually was there in these journalistic articles, what did the Baroness’s will really say, and – if not vampirism – what could explain the extremely odd decorations on her tomb? Keep reading and we’ll try to find out.

How Much Truth Is There in the Sinister Legends of Baroness Demidoff’s Bizarre Will and ‘Vampiric Tomb’?

For some time, people have tried to explain the weird contents of the Baroness’s will and the strange legends surrounding her. It’s been suggested that the stipulations in her last will and testament came from a fear of being interred in her mausoleum alive. A terror of live burial was common in the 18th and 19th centuries. Medical advances in the understanding of coma-like states had led people to realise it was possible for one to appear dead, be buried then wake up underground or sealed in the tomb.

These fears can be seen in fiction like Frankenstein and Dracula – books which obsess over the blurry boundaries between death and life and the dark possibilities of reanimation – as well as in the stories of Edgar Allan Poe. Some coffins were fitted with bells and flags, enabling people who suffered overhasty burial to signal to those on the surface. Or the ‘dead’ were buried with loaded pistols so they could end their anguish if it turned out a terrible mistake had occurred. Might Baroness Demidoff’s will have been an attempt to lure a watcher who could raise the alarm if he saw movement in her crystal coffin? Were the mirrors to make sure any such stirrings wouldn’t be missed?

This argument – considering the widespread fears of the time – might be compelling, but it’s unlikely to be accurate. As mentioned above, most of our knowledge of Baroness Demidoff’s will comes from newspaper reports and an analysis of these soon provides a simpler explanation. The dark fairy tale of the glass-coffined princess in Père Lachaise Cemetery appears to have sprung from nothing more than the 19th-century equivalent of ‘fake news’.

The greatest giveaway is the date of the articles. Research by Chris Woodyard – author of the Victorian Book of the Dead – has found that the earliest printed reference to the Baroness’s morbid myth crops up in the Chicago Daily Tribune on 25th October 1893. The Tribune’s short article claims that ‘five years ago a Russian princess died leaving a large fortune’ before going on to give details of the glass coffin, a five-million-franc reward and the requirement for anyone who wanted this cash to remain in the mausoleum for a year. Immediately, we can see an issue – the article implies the baroness died in 1888 when in fact she passed away in 1818.

The Chicago Daily Tribune article was picked up by newspapers in the United States, in France and throughout the world, leading to a deluge of letters from those willing to endure the ordeal. Another Chicago newspaper – probably the Chicago Herald – published an article on November 15th 1893 also stating the ‘Russian Princess’ had died five years earlier. When the American J.H. Davis wrote his charming letter – also in 1893 – asking to undertake the challenge, he enclosed ‘an article from the Chicago Herald to the effect that one million dollars are left by a Russian Princess to the person who will watch her tomb for the space of one year.’

Even at the time, it didn’t take most of the press long to see through the hoax around Baroness Demidoff’s will. Articles were published around the world giving details of the legend then thundering against the fraud it had sprung from. In January 1894, the San Francisco Morning Call denounced the story as ‘a very grim hoax’. The New Zealand Herald, on 17th February 1894, wrote, ‘How this story got circulated, no one knows, not even the conservator of Père Lachaise Cemetery, who has used every effort to discover its author. To put an end to the fable and to the streams of letters, he has sent notes to the journals contradicting the story, but they have not yet met with so much credence as the legend of the Princess’ million.’ In April 1894, the Boston Herald published ‘A Bogus Special about the Will of a Princess’, stridently condemning ‘a certain Chicago newspaper as the cause of all sorts of emotions and of semi-diplomatic annoyances to the American embassy, to the prefecture of police and to the municipality of this great capital.’ This lamentable news item, the Boston Herald tells us, had aroused ‘the ambition of all the cranks in the country’.

A quiet lane in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris (Photo: X Days in Y)

I can’t help wondering, however, if these articles – which devoted more space to describing the macabrely fantastical legend than debunking it – didn’t increase the myth’s popularity and keep the torrent of letters from eager candidates gushing in. In 1896, Baroness Demidoff’s grim fame received fresh impetus from an article in Le Temps, which depicted the story in the manner of a morbid fairy tale. Even years later, the legend would surge into the popular consciousness from time to time. In 1932, the Emporia Gazette described how ‘some time last August an ex-soldier arrived at the cemetery and solemnly announced that he had come to win the million francs offered … his advent, so the authorities have informed reporters, was the beginning of a veritable procession of adventurers all equipped with the same tale and paraphernalia and all eager to pass a year in the tomb of the Russian Princess … Not only this, but letters have been received by the cemetery authorities from persons in Morocco, Tunisia, the Sudan and Indo-China, who desire to undergo the ordeal. Those who have appeared at the cemetery in person, although carefully interrogated by the authorities, have either declined or refused to divulge the source of their information.’

So it appears that the legend of Baroness Demidoff’s will was likely a creation of a journalistic pen (or typewriter) to provide content on a slow news day – a short article that then caused an unexpected sensation around the globe, memories of which lingered in the collective imagination for decades. There is, of course, the possibility that the articles may have been based on oral folklore that had grown up around the Baroness’s tomb, but there’s no way of proving this. As for the Baroness’s will itself – the document that would clear much of this speculation up – no one seems to know where it is or what is says. A figure with the wealth and social status of Baroness Demidoff would have likely left a last will and testament, but there is (perhaps mysteriously) no surviving record of it.

But what about the vampiric symbols on Baroness Demidoff’s tomb? The tomb does bear unusual emblems, though some of these – like hammers and depictions of small creatures, probably weasels – are references to the sources of the Demidoff family wealth in the metalworking and fur industries. The wolves’ heads function as water-spouting gargoyles and though bats are an unusual and somewhat sinister choice of tomb ornamentation, they’re not totally unheard of – another mausoleum in Père Lachaise is decorated with the creatures. The eights in the Baroness’s death date – as records show – simply refer to the day she died. As for the tomb’s location on the Path of the Dragon and Alley of Acacias, the case for any deliberate siting of the tomb on these thoroughfares must be weakened by the fact the tomb was moved from the 39th Division of Père Lachaise to the 19th. There’s also nothing in what we know of Baroness Demidoff’s life or her upbeat personality to suggest any dabblings in the darker aspects of the occult, let alone vampirism.

Hammers and weasels – representing the Demidoff’s sources of wealth – on Baroness Demidoff’s tomb in Père Lachaise Cemetery. (Photo: Guilhem Vellut)

Spooky and atmospheric Victorian-era cemeteries do, however, have a strange capacity to attract otherworldly legends. A vampire was once rumoured to lurk in London’s Highgate Cemetery while another vampire panic took place in Glasgow’s Southern Necropolis. In Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia, a tomb is rumoured to be decorated with vampiric signs and emblems, rather like the Baroness’s resting place. In London’s Brompton Cemetery, a striking Neo-Egyptian mausoleum is said to be either a Victorian time-travelling contraption or a teleportation device.

Mausoleums in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris. (Photo: Whitty McCloud)

Whether or not Père Lachaise Cemetery contains a glass-casketed vampire princess – or whether or not you dare to peer into or hang around Baroness Demidoff’s mausoleum – the necropolis is certainly worth a visit. As well as being Paris’s largest cemetery, it’s the city’s biggest park. Paths thread pleasantly through the tree-shaded, landscaped grounds – grounds full of the most fascinating and beautiful tombs. Père Lachaise is like a history book of marble, granite and earth, hosting the graves of numerous cultural figures, such as Jim Morrison, Oscar Wilde, Édith Piaf, Honoré de Balzac, Sarah Bernhardt, Max Ernst, Gertrude Stein and Guillaume Apollinaire. But one of the graveyard’s most famous tombs – whether as the result of press sensationalism or something more supernatural and sinister – will always be the imposing mausoleum of the Russian baroness who made her eternal home in the French capital.

(This article’s main image – showing Baroness Demidoff’s tomb in Père Lachaise Cemetery – is courtesy of Guilhem Vellut.)

This is a terrific blog. You maintain great suspense even though you eventually debunk it. I’ve been to this Paris cemetery to see Jim Morrison and the author Colette’s graves. I’ll have to look for this one if I visit again. Thanks!

Thanks, Kimberly. Pere Lachaise is certainly a fascinating cemetery. While researching the Baroness Demidoff article, I found out so much interesting information that I plan to revisit the cemetery in a future blogpost.

A princess and ‘fake news’ – now where have we heard that before… what a timely post. And fascinating! Thank you!

You’re very welcome, Gil. Glad you enjoyed Pere Lachaise’s strange legend of Baroness Demidoff and her glass coffin!

Thank you for a fantastic (in all senses of the word) read! I live in Paris and often visit Père Lachaise Cemetery. As you wrote, it’s a beautiful and fascinating place. But I had no idea about this legend. I love how you shared the story and then investigated it – but I have to admit, I still want to believe it’s true!

Many thanks, Alysa, glad you enjoyed the post. Baroness Demidoff’s story is certainly one of Pere Lachaise’s most fascinating myths.