A terrifying creature haunts the British psyche, an apparition our ancestors have long feared to meet late at night on quiet lanes, in city alleys or on gloomy isolated moors. This creature, or spectre, is an abnormally large black dog with burning red eyes. Sometimes the dog will attack; sometimes glimpsing it foreshadows death or tragedy; occasionally – very occasionally – the black dog may be helpful, shepherding lost travellers or guarding people from harm.

Sometimes the dog is headless. Sometimes it merely appears before you ominously; at other times it follows or pads around you, sometimes with the sound of dragging chains. Sometimes the beast is silent; at other times packs of black dogs hurtle over moors or fens, barking and howling in a frenzied hunt. The creature is associated with electrical storms and is notorious for haunting crossroads, prisons and the sites of gallows and gibbets. The beast has worked its way into Britain’s literature, with Emily and Branwell Brontë, Bram Stoker, Arthur Conan Doyle and J.K. Rowling among those inspired by black dog legends.

In different parts of the country, the black dog has different names: Barghest, Gytrash and Padfoot in Yorkshire; Moddey Dhoo on the Isle of Man; Old Shuck in East Anglia; Yeth or Whist Hound in Devon; and Gwyllgi – or ‘dog of darkness’ – in Wales. While these manifestations of the black dog archetype have their dissimilarities, they no doubt represent variants of the same haunting presence – the hulking, burning-eyed cur whose apparition has long been dreaded.

Phantom black dogs are rumoured to haunt many parts of Britain. (Image: tardust777)

But how do the antics of this petrifying pooch differ around Britain? Where might the legends of black dogs come from and what dark obsessions deep in the human psyche could they symbolise? How far back does the folklore of these fearsome creatures go? And does the black dog belong in a superstitious past or has anybody glimpsed it in recent decades?

I’ve selected seven black dog legends to look into. While it might generally not be a good idea to walk alone over moors or venture down unlit urban snickleways late at night, you might be even more reluctant to do so after reading these accounts.

Number One: the Black Dog of Newgate Prison, London

From 1188 to 1902, Newgate Prison was one of London’s most notorious features. Evolving from cells in a gatehouse in the city walls, the prison was at various times extended, burnt down, demolished, rebuilt, reformed and allowed to fester, but the stories coming out of the jail were always grim, not to say horrific.

In the ill-lit, badly ventilated, overcrowded, filthy jail disease spread rapidly. Warders beat, abused and extorted inmates, sometimes even chaining them to walls and leaving them to starve. Lice and bedbugs were so prevalent, you could hear them crunch under your feet. While having financial means could secure you a modicum of comfort, the jail’s worst conditions saw people chained in the basement in what was basically a sewer. Newgate did, however, have a bar and the prisoners who could afford it seem to have been perpetually drunk. The stench from the jail was so bad that passers-by clasped vinegar-soaked handkerchiefs to their noses. Newgate was demolished in 1904 and the Old Bailey now occupies most of its site though some cells are preserved in the cellar of a nearby pub.

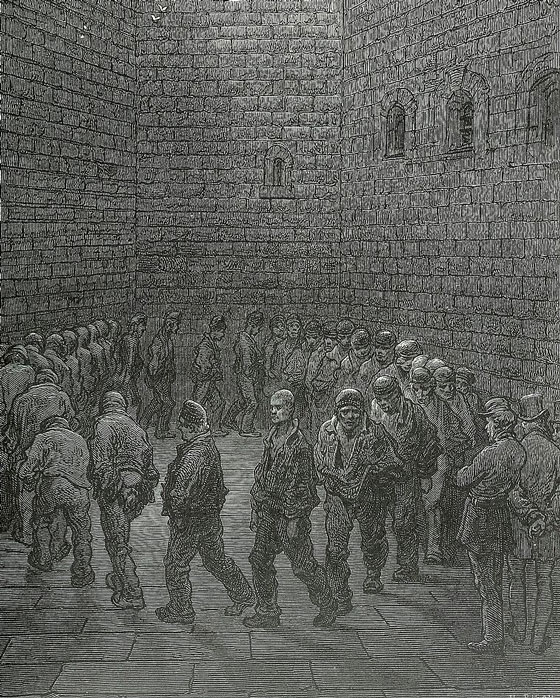

The exercise yard in Newgate Prison by Paul Gustave Dore

It’s perhaps inevitable that such a sinister institution evolved its own black dog legend, with its canine ghost darkly symbolic of centuries of suffering. The story goes that in the reign of Henry III (1216-1272), a scholar accused of sorcery was sent to Newgate to await trial. Unfortunately for him, his imprisonment coincided with a terrible famine that was sweeping through England, a famine so bad it had prompted some inmates of Newgate to resort to cannibalism.

The weedy scholar, unable to defend himself, soon fell victim to these depraved inmates and was killed, dismembered and gobbled up. Shortly afterwards, prisoners began seeing the spectre of a huge black dog padding the jail’s corridors, a spectre they became convinced was the sorcerer come back to take revenge on those who’d eaten him. Sure enough, the dog began to hunt down and consume those responsible for that crime.

The remaining prisoners who’d scoffed the sorcerer were so terrified they plotted to break out of the jail and managed to escape by murdering some guards. But while they were free of Newgate, they were not free of the dog. One-by-one, the black dog sought them out, killed and ate them.

The first written evidence for this story appears in a publication with a woodcut cover, dated 1596 and entitled The Discovery of a London Monster, called The Blacke Dogg of Newgate: Profitable for all Readers to Take Heed by. The legend is probably, however, older than this. The pamphlet’s author is one Luke Hutton, an inmate of Newgate who claimed a stranger – ‘a poor thin-gut fellow’ – had once narrated the tale to him in the Black Dog Public House. Upon concluding his terrifying account, the stranger tells Hutton the legend is untrue, saying the only black dog in Newgate is ‘a great blacke Stone standing in the dungeon called Limbo, the place where the condemned prisoners are put after their judgement’ against which some anguished felons have dashed their brains out.

An illustration from a 1638 edition of the book ‘The Discovery of a London Monster Called the Black Dog of Newgate’

Hutton appears to have written the pamphlet as a morality tale, to draw attention to prison conditions and the behaviour of his fellow inmates during a period in which life in Newgate was especially appalling. Hutton dedicated the booklet to the Lord Chief Justice John Pophame in the hope its moral message might help secure his release, which it seems to have done.

Despite such scepticism, the black dog has been sighted in and around Newgate over the centuries, especially on evenings before executions. Within the prison there was once an alleyway called Dead Man’s Walk – the snicket acquired its name because condemned criminals walked down it to their executions. The names of all the convicts who plodded this grim passage were etched into its walls and many were buried under its flagstones. Dead Man’s Walk was demolished along with the rest of the prison in 1904. Where it ran is, however, close to Amen Court, a precinct attached to St Paul’s Cathedral containing canons’ houses. Part of Amen Court is bounded by what was once a wall of Newgate.

Amen Court is said to be haunted by Newgate’s black dog. The spectre appears as a shapeless black form which glides around the court and nearby streets and slithers along the top of the prison’s remaining wall. The ghost gives off a disgusting stink and is often accompanied by the sound of footsteps dragging, a noise reminiscent of prisoners trudging to their deaths.

Amen Court with the former wall of Newgate Prison on the left – does the black dog’s ghost slither along its top? (Photo: Knowledge of London)

Number Two: the Barghest of Yorkshire – a Sinister Black Dog and Herald of Death

A particularly ominous black dog – the Barghest – can be found in the folklore of Yorkshire and north-east England. The Barghest heralds death. If a Barghest lays down across the threshold of your house, it’s a sign you’ll pass away soon.

If a person of local importance is about to die, the Barghest will appear and all the other dogs of the neighbourhood will fall in behind it in a kind of funeral procession, barking and howling mournfully. If, while the Barghest is leading its solemn parade, anyone obstructs it, the dog will gouge them with its claws, leaving wounds that never heal. In his Notes on the Folk-lore of the Northern Counties of England and the Borders (1879), William Henderson recalled that his ‘informant, a Yorkshire gentleman, lately deceased, said he perfectly remembered the terror he experienced when a child at beholding this procession before the death of a certain Squire Wade, of New Grange.’

A Barghest is said to haunt Troller’s Gill, a lonely limestone gorge south-east of Grassington in the Yorkshire Dales. A ballad – The Legend of Troller’s Gill – is recorded in William Hone’s Everyday Book (1830). This folksong tells of a man who clambered up to ‘the horrid gill of the limestone hill’ to try to summon the Barghest with ritual magic. The man’s body was found with uncanny maul marks on its breast. Another Barghest was rumoured to prowl a tract of wasteland called the Oxwells between Wreghorn and Headingly Hill, near Leeds.

Some argue ‘Barghest’ comes from the term ‘Berg-geist’ meaning ‘mountain ghost’; others claim the name derives from ‘Bur-ghest’ or ‘town ghost’. Perhaps both etymologies are right as the Barghest seems equally comfortable in the countryside and the city. It’s whispered that a Barghest haunts York, preying after dark on lone wanderers in the city’s winding narrow alleys, known as snickleways. With its massive jaws and yellow fangs, the dog devours these wayfarers.

Might a phantom black dog haunt York’s narrow snickleways? (Image: VAMzzz)

A Barghest is rumoured to roam Whitby, the coastal town that appears in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. In the Whitby section of the novel, the Count transforms into an enormous black dog – a beast that may have been inspired by local Barghest legends. The Barghest also roves the moors around Whitby – locals say if you’re unlucky enough to hear its chilling howl at night, it means death is coming soon. Soon claim you’ll pass away before dawn.

Though usually depicted as a large shaggy black dog with blazing red or green eyes, the Barghest has shapeshifting powers. In Northumberland and County Durham, the Barghest can appear as a type of household elf. A Barghest that lived close to Darlington could manifest as a headless man who’d vanish in a flash of flame, a headless woman, a white cat and even an unearthly rabbit. The Barghest can also make itself invisible. Perhaps this shapeshifting ability is reflected in the fact some think its name originates from ‘Bar-geist’ or ‘bear ghost’. Others, though, maintain – again referencing the animal’s links with death – that ‘Barghest’ comes from ‘bahr geist’, meaning ‘ghost of the funeral bier’.

Some say the Barghest is accompanied by the sound of rattling chains and that – like vampires – the beast can’t cross running water.

A Barghest was said to haunt the treacherous moors around Whitby – monuments and way markers had the function of helping travellers keep their bearings in thick fog. (Photo: Whitby Gazette)

Number Three: the Gytrash of Northern England – an Ambiguous Shapeshifter with a Brontë Connection

The Gytrash is a black dog that lingers by the lonely moorland and marsh roads, forest paths and high passes of northern England. Often malevolent, the dog delights in leading travellers dangerously astray, but sometimes it can be helpful, guiding them onto safe tracks.

Like its cousin the Barghest, the Gytrash is a shapeshifter and can appear as a crane, mule or horse. In its equine aspect, the Gytrash is known in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire as the Shagfoal – a phantom horse, mule or donkey with burning eyes. In this form, the creature is utterly wicked. The Gytrash could be partly a personification of the dangers that plagued travellers in the days of substandard unlit roads, highway men, and unreliable maps and methods of transport.

The Gytrash – again, like the Barghest – can be a portent of doom. According to the English Dialect Dictionary (1898-1905), the Gytrash could adopt the guise of ‘an evil cow whose appearance was formerly believed in as a sign of death.’

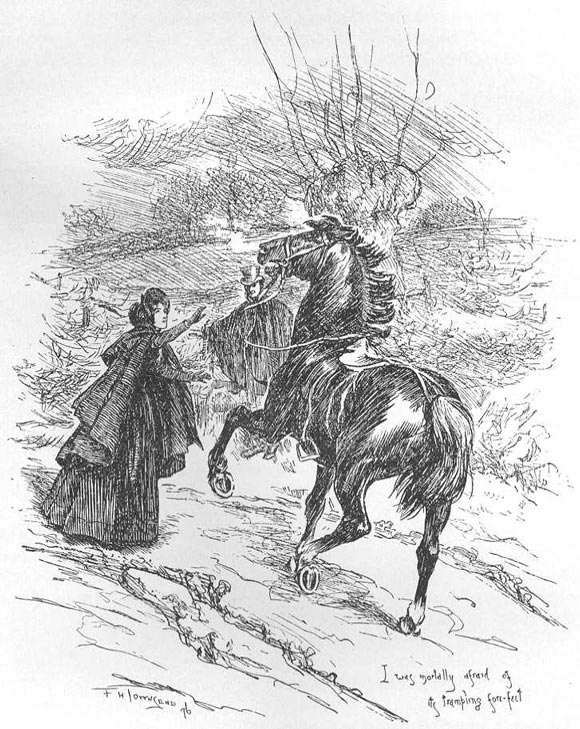

The most famous mention of the Gytrash – and possibly the first ever committed to print – occurs in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. Before Jane’s first meeting with the Byronic hero Mr Rochester – out in a lonely country lane – she’s reminded of the spooky tales she’s heard of this black dog:

‘As this horse approached, and as I watched for it to appear through the dusk, I remembered certain of Bessie’s tales, wherein figured a North-of-England spirit called a “Gytrash”, which, in the form of a horse, mule or large dog, haunted solitary ways, and sometimes came upon belated travellers, as this horse was now coming upon me. It was very near, but not yet in sight; when, in addition to the tramp, tramp, I heard a rush under the hedge, and close down by the hazel stems glided a great dog, whose black and white colour made him a distinct object against the trees. It was exactly one form of Bessie’s Gytrash – a lion-like creature with long hair and a huge head … with strange pretercanine eyes … The horse followed – a tall steed, and on its back a rider. The man, the human being, broke the spell at once. Nothing ever rode the Gytrash: it was always alone.’

Jayne Eyre encounters the ‘Gytrash’ – a ghost legend says can appear as a black dog or horse.

And so these fearsome Gytrashes turn out to be Mr Rochester’s utterly ordinary horse and harmless dog, Pilot. Charlotte Brontë uses the scene with the ‘Gytrash’ to subtly mock the overly romantic and gothic associations Jane will soon attach to Rochester. Having said that, Rochester is in some ways like the Gytrash: a dark, haunted, ‘spectral’, often solitary character prone to shifting shape and generating illusion.

It’s also interesting that Jane’s formed her ideas of the Gytrash from the stories of her maid, Bessie. In Victorian culture, servants were often assigned the function of transmitters of folklore, reflecting the notion that – in a world scarred by industrialisation and filled with mechanical progress – the ‘lower orders’ still retained a vital connection with the mythic past. Jane says, ‘All sorts of fancies bright and dark tenanted my mind: the memories of nursery stories were there amongst other rubbish; and when they recurred, maturing youth added to them a vigour and vividness beyond what childhood could give.’

Charlotte wasn’t the only Brontë whose literary output was influenced by the Gytrash. Branwell Brontë wrote a short story called Thurstons of Darkwall. Branwell’s tale – based around Ponden Hall, a real-life house which may have been a model for Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights – features a Gytrash. The story emphasises the Gytrash’s shapeshifting capabilities. In addition to appearing as a black dog, the spectre can take the form of ‘an old dwarfish and hideous man, as often seen without a head as with one’, as well as a calf and even a flaming barrel. Branwell’s phantom was based on an apparition that people claimed to have witnessed on the wild and isolated moors around Haworth.

Number Four: East Anglia’s Old Shuck – a Devilish Black Dog and Destroyer of Churches

Old Shuck – also known as Black Shuck – is a terrifying, even demonic, phantom in the form of a black dog that haunts Norfolk, Suffolk, northern Essex and the Cambridgeshire fens. Sometimes Old Shuck attacks wayfarers; sometimes the dog’s appearance foreshadows deaths – either of the person who glimpses it or of someone close to them. The term ‘shuck’ may derive from an old word for ‘devil’ or ‘fiend’ or from a word meaning ‘terrifying’ or it might simply refer to the shagginess of the dog’s coat.

The first mention of the name ‘shuck’ in print comes from an 1850 edition of the journal Notes and Queries, in which the Reverend E.S. Taylor writes about ‘Shuck the dog fiend’, stating, ‘This phantom I have heard many persons in East Norfolk, and even in Cambridgeshire, describe as having seen as a black shaggy dog, with fiery eyes and of immense size, who visits churchyards at midnight.’

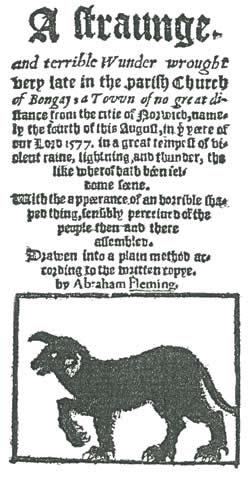

East Anglian black dog legends, however, go back far earlier. On Sunday 4th August 1577, a fiery demon in the form of a black dog appeared at Blythburgh Church, Suffolk, during a tremendous storm ‘consisting of raine violently falling, fearful flashes of lightning, and terrible cracks of thunder, which came with such unwonted force and power … the church did as it were quake and stagger.’ A service was taking place and the dog sprinted up the aisle, killing a man and boy, badly burning a man’s hand, ‘blasting’ other congregants, and bringing the church steeple crashing down through the roof. As the fiend exited the church, he left burn marks and incisions from his flaming talons on the doors.

The front cover of the 1577 pamphlet ‘A Straunge and Terrible Wonder’

The demon then headed over to St Mary’s Church in Bungay. Here, in an assault described in the pamphlet A Struange and Terrible Wonder (1577) by Abraham Fleming, this ‘black dog or the divel in such a likeness’ was soon ‘running all long down the body of the church with great swiftnesse, and incredible haste’. The dog ‘passed between two people as they were kneeling … occupied in prayer … (and) wrung the necks of them both at one instant cleane backwards, in somuch that … where they kneeled, they strangely died.’

Not content with this slaughter, Old Shuck continued the carnage. A piece of local verse states: ‘All down the church in midst of fire, the hellish monster flew, and passing onward to the quire, he many people slew.’ Like at Blythburgh, the dog left scorch marks on the door of St Mary’s.

The accounts of Old Shuck’s rampages in Blythburgh and Bungay are probably overdramatic memories of a catastrophic storm. It seems Abraham Fleming put his booklet together from exaggerated oral testimonies. Fleming worked as an editor for several London printers so it may have been in his interest to make sure his rendering of the story was suitably spectacular. The burn marks on the churches’ doors – still referred to as ‘the Devil’s fingerprints’ – are more likely to have been inflicted by candles.

Burn marks on Blythburgh Church door, supposedly left by Black Shuck. (Photo: Atlas Obscura)

Legends of spooky black dogs in this part of England have, however, persisted over the centuries. In Highways and Byways in East Anglia (1901), W.A. Dutt describes Old Shuck as a being who ‘takes the form of a huge black dog, and prowls along dark lanes and lonesome field footpaths, where, although his howling makes the hearer’s blood run cold, his footfalls make no sound.’ Dutt ascribes a curious feature to Old Shuck: ‘You may know him at once, should you see him, by his fiery eye; he has but one, and that, like the Cyclops’s, is in the middle of his head.’

Encountering Black Shuck will ‘bring you the worst of luck: it is even said that to meet him is to be warned that your death will occur before the end of the year. So you will do well to shut your eyes if you hear him howling.’

An artist’s impression of Old Shuck, based on W.A. Dutt’s description. (Image: Mattias Thatch)

Despite all this, Old Shuck, like other black dogs, can be ambiguous and there have been accounts of the creature being companionable and guiding lost travellers.

But do legends of Black Shuck belong firmly in the past? The poet Martin Newell – while doing research for his epic poem Black Shuck: The Ghost Dog of Eastern England – talked to East Anglian locals. He was surprised by how many believed the legends and claimed to have seen Black Shuck.

‘Ah, you’re writing about that now, are you?’ a Norfolk shopkeeper stated. ‘Well, be careful.’

A woman Newell spoke to said she’d seen Black Shuck near Cromer in the 1950s when coming home from a dance and a man told him he’d spotted the dog while crossing marshes near Felixstowe. Newell also found a newspaper article from the 1930s about a midwife who – cycling on a winter night near the Essex village of Tolleshunt Darcy – had been followed by Old Shuck. However fast she pedalled through the country lanes, the black dog kept up with her. Eventually, the apparition vanished.

Number Five: the Isle of Man’s Moddey Dhoo – a Sinister Black Dog That Haunted Peel Castle

According to a legend recorded by the English poet and topographer George Walden (1690-1730), Peel Castle on the Isle of Man was once haunted by a Moddey Dhoo. ‘Moddey Dhoo’ simply means ‘black dog’ in the Manx language and this specimen apparently looked like a giant shaggy-haired spaniel. Though such a creature might sound somewhat comical, all who came into contact with this entity soon realised there was something otherworldly and sinister about it.

The Moddey Dhoo had been seen in every room in the castle, but – during the reign of Charles II – it began frequenting the guard chamber. As soon as the guards had lit the candles in the evening, the black dog would come padding along a certain corridor and into the room, where it lay down before the fire in front of all the soldiers. Then, as day began to break, the Moddy Dhoo would rouse itself and trot off back down the same passage.

Was Peel Castle home to the phantom black dog known as the Moddey Dhoo? (Photo: July Wind)

This corridor – via an ancient church – connected the guardroom with the captain of the guard’s quarters. The soldiers had to walk along it to return the castle’s keys at the end of the night. After the dog started padding down the dark narrow passageway, they never did this alone, but always went in twos.

The guards had been in the habit of drinking ale and telling stories to make their nightshift pass more quickly, but after the dog began visiting their room, they became more sombre. Still, they pretended to ignore the apparition and after some time grew accustomed to the presence of the phantom pooch, though they were still unsettled by it.

One soldier, however, became too relaxed around the strange spaniel. One night, he got drunk and boasted loudly that he’d be the one who’d take the keys back to the captain in the morning and that – moreover – he’d do it by himself. He wasn’t scared of any dog, whether normal or supernatural. It wasn’t even the soldier’s turn to take the keys and his friends tried to talk him out of his mad plan, but – when daylight started to appear – he snatched the keys from their hook and strode out of the guardroom. The Moddey Dhoo got up calmly from its place by the fire and followed him.

A couple of tense minutes passed before the most terrifying screams and wails resounded from the passage. The soldiers wanted to help their comrade, but were all too frightened, and soon they heard someone staggering back towards their room. The door swung open and their colleague tumbled in, his face utterly white and contorted with terror, his eyes bulging with fear. The man was unable to speak so he couldn’t tell his friends of the horrors he’d endured. He soon sickened and a few days later was dead. As for the black dog, no one ever saw it again anywhere in Peel Castle.

There seems to have sometimes been a tradition in Britain and Scandinavia of burying black dogs in graveyards or in the foundations of churches in the hope their ghosts would protect such sites from evil spirits and the Devil. The Moddey Dhoo’s corridor ran through an old church and excavations there in 1871 uncovered the grave of a bishop who’d died in 1247. At the bishop’s feet was the skeleton of a large dog.

Though the Moddey Dhoo may have disappeared from Peel Castle, phantom black dogs have been seen elsewhere on the Isle of Man. A black dog that haunts a field near Ballmodda is termed an ‘ordinary Moddey Dhoo’ in contrast to the headless variety, one of which is said to appear in a farm lane in Ballagilbert Glen. A Moddey Dhoo – which, according to some, is as big as a calf and has burning plate-sized eyes – has been spotted at Milntown Corner on the outskirts of Ramsey.

Number Six: the Black Dogs of the South West – Yeth Hounds, Whist Hounds, the Devil’s Dandy Dogs and The Hound of the Baskervilles

The Hound of the Baskervilles may be based on black dog legends from the south west. (Image: Visit Dartmoor)

Devon folklore states that large black dogs known as Yeth Hounds are the souls of children who passed away before they could be baptised. The Yeth Hound – which is headless – wanders through woods at night howling.

Another species of Devon black dog is the Whist Hound. Though some regard them as similar to Yeth Hounds, they seem more sinister. They hunt in packs across Dartmoor and it’s rumoured the huntsman is the Devil himself. Whist Hounds are said to haunt Wistman’s Wood – a spooky high-altitude tangle of moss-covered oak trees – as well as the area surrounding the Dewerstone, an Iron-Age hillfort on a rocky outcrop above the River Plym. Any mortal dog who hears the horrendous howling of the Whist Hounds soon dies.

A different Devon legend claims the spirit of Sir Francis Drake – as a punishment for his obsession with the occult – is forced to drive a black hearse coach through the night between Taverstock and Plymouth. Headless horses pull the coach, which is followed by demons and black headless hellhounds. This story could be a variant on the wild hunt motif, in which a mythological figure leads a band of phantom huntsmen and yelping spectral dogs. Those who, in various places, are made to lead the hunt – usually as a penalty for some sin – include Cain, the Devil, King Arthur, King Herod, Odin and Herne the Hunter. The black coach could be viewed as a relatively modern addition to this ancient archetype.

Yet another piece of Devon black dog folklore tells of an aristocrat named Richard Cabell. Cabell, a ‘monstrously evil man’ and a squire of Buckfastleigh on Dartmoor’s southern fringe, is – among other crimes – rumoured to have murdered his wife and sold his soul to the Devil. When he died, local people were relieved, but they soon realised they were far from free of the wicked squire.

Cabell had been an obsessive hunter and it seems he saw no reason why death should interfere with his enjoyment of this pastime. On the night of his burial, a pack of ghostly black dogs came across Dartmoor to stand howling at his tomb. Cabell’s ghost began leading these dogs – in his own version of the wild hunt – over the moors at night, especially on the anniversary of his death. If Cabell didn’t feel like going out hunting, the dogs hung around his grave, disturbing Buckfastleigh’s residents with howling, barking and unearthly shrieks. Determined to quieten Cabell’s evil soul, his neighbours laid a heavy slab over his grave and built a ‘prison-like’ mausoleum above it, a plan which appears to have been successful. Even to this day, Buckfastleigh youngsters dare each other to stretch their arms through the mausoleum’s barred window and touch Cabell’s tomb while hoping his wicked spirit won’t seize them.

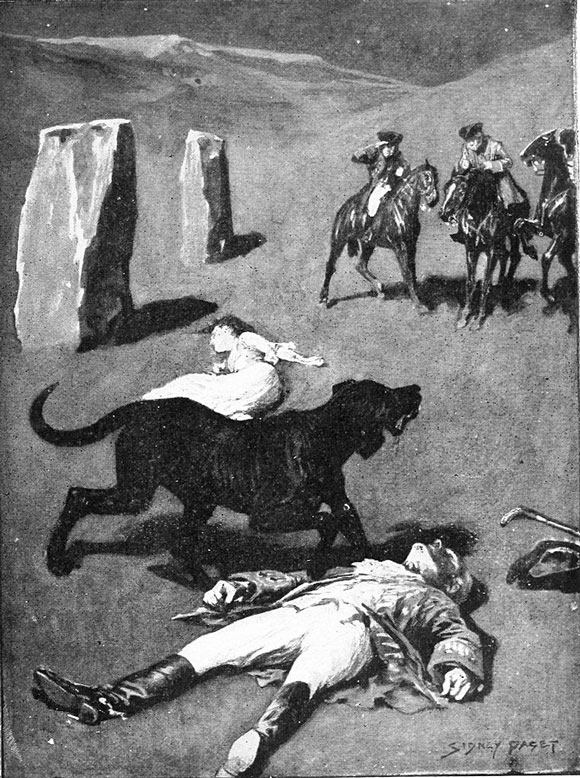

Some say Arthur Conan Doyle heard about this legend while visiting a friend in the area and that this prompted him to write his Sherlock Holmes mystery The Hound of the Baskervilles. Apparently, Baskerville was the name of one of the coachmen at the house he stayed at. Set mostly on Dartmoor, the book tells the story of a devilish dog – ‘an enormous coal black hound, but not such a hound as mortal eyes have ever seen’ – that has for many years haunted the aristocratic Baskerville family. This haunting began as a punishment for the debased behaviour of Hugo Baskerville, a character with similarities to Richard Cabell. The dog appears just before the deaths of the family’s heirs, deaths which are often disturbingly premature.

An illustration by Sidney Paget from The Hound of the Baskervilles

It’s not clear, however, how such apparent influences square with Doyle’s own statements. When asked about the origins of his novel, Doyle said, ‘My story was really based on nothing save a remark of my friend Fletcher Robinson that there was a legend about a dog on the moor connected with some old family.’ Bertram Fletcher Robinson, a Daily Express journalist, explored Dartmoor with Doyle, supplying him with local legends and accounts of Devon oddities. Doyle paid him a third of the profits from the serialisation of the novel in gratitude.

Some, on the other hand, claim the influences for The Hound of the Baskervilles came from outside the south west. Doyle once holidayed in North Norfolk, near Cromer, an area where legends of Black Shuck are well-known. During his trip, he stayed at the pre-Gothic Cromer Hall, which in many ways matches Doyle’s fictional Baskerville Hall. Another possible source of inspiration was Crowsley Park in Oxfordshire. The gates to this estate feature statues of hellhounds with spears through their mouths while another fearsome dog can be seen above a lintel on the front of Crowsley Park House. This estate was owned by the Baskerville family and a daughter, Florence Baskerville, married one of Doyle’s friends. Perhaps all these things came together with the legends Doyle heard in the south west to inspire his idea of a hellhound-haunted family.

As for Richard Cabell, the mausoleum supposedly put up to quieten his unruly spirit contains Cabell family tombs older than his. It’s unlikely, therefore, to have been built after his death. Cabell is also unlikely to have killed his wife as she’s mentioned in his 1671 will.

If we travel further west, we’ll find black dog legends in Cornwall. Black dogs in that county have been known to haunt tumuli, lonely roads and the scenes of tin mining accidents. Dark-coloured canines also feature in Cornish versions of the wild hunt. The vicinity of the village of St Germans is haunted by a pack of dogs that belonged to a wicked priest named Dando. Dando was a keen huntsman who regularly committed the sacrilege of hunting on the Sabbath. He was also a heavy drinker who – after one Sunday hunt – declared that if his companions couldn’t give him enough booze he’d go to hell to get it. A strange huntsman stepped forward and offered Dando a drink before seizing and dragging him down to the netherworld. Dando’s Dogs can still be heard on Sunday mornings, running after game or seeking their lost master.

Phantom black dogs allegedly roam the moors 0f south-west England. (Image: Ghostly Activities)

Another legend – sometimes confused with that of Dando – concerns the Devil’s Dandy Dogs. Satan himself is in charge of this pack and his dogs are not just phantoms but genuine flame-breathing hellhounds. This terrifying hunt roams the moors and any travellers who hear it are urged to kneel and pray that the Dandy Dogs don’t come in their direction. Black hellhounds are also rumoured to pursue Jan Tregeagle, a damned soul who escaped from hell. Jan is said to have once haunted the eerie Dozmary Pool high on Bodmin Moor, where – on stormy nights – his shrieks could be heard along with the howls of the infernal dogs chasing him.

Number Seven: the Church Grim – a Guardian Spirit in the Form of a Black Dog

Legends from Britain and Scandinavia state that certain churchyards are haunted by a ‘Church Grim’, a spirit that usually appears as a large black dog. Rather than being a malevolent entity, the Grim protects the churchyard from all who would desecrate it, including vandals, witches, warlocks, thieves and even the Devil.

A tradition, apparently, once maintained that the spirit of the first person to be buried in a churchyard would be tasked with guarding it. In Scotland, the last person buried in a cemetery would have to be its guardian until a new interment took place. To save the spirits of the departed from these onerous duties, a large black dog would be buried either in the churchyard or in the foundations of the church itself, especially under its cornerstone.

Some say the black dog’s ghost tolls the church bell at midnight on the eve of the death of a local resident. During the funeral service, the clergyman might spot the Grim staring out from the church tower and from the dog’s behaviour be able to tell if the deceased will go to hell or heaven. The Church Grim is also associated with stormy weather. Though normally manifesting as a black dog, the Grim has been known to take the form of a horse or pig.

Honourable Mentions from Britain’s Many Black Dog Legends

Black dog legends are widespread across the UK and versions of this myth have been recorded in almost every English county. Yorkshire, especially, seems a centre of black dog folklore. As well as the Barghest and Gytrash, there’s the Padfoot. You might encounter this creature close to Leeds, Wakefield or Bradford. It apparently follows people with a soft padding sound, sometimes augmented by the clanking of chains. A harbinger of death, the Padfoot can let rip a roar like no earthly animal. You shouldn’t attack or try to speak to the Padfoot – doing so will put you in its power. A man who once kicked the dog found himself seized by the supernatural hound. Pulled through a ditch and hedge, the man was dragged all the way back to his house before being dumped under a window.

Yet another black dog that roves Yorkshire – and parts of Cumbria – is the Cappelthwaite. This dog first appeared on a farm near Milnthorpe, Cumbria. He lived in a barn called Cappelthwaite Barn, from where he got his name. The dog was helpful to the farm’s residents, rounding up sheep and assisting with chores, but was malevolent and mischievous towards everyone else. The dog was eventually expelled by the local vicar and has since roamed the countryside. Though the Cappelthwaite prefers the form of a black dog, he can materialise as any four-legged animal.

Some particularly curious black dogs are known as Gabriel Hounds. They are hounds with human faces that fly yelping through the air and are heard far more frequently than seen. If they hover noisily over a house, it’s a sign death or calamity will afflict those living there. Some say the dogs are spirits of unbaptised infants; others that Gabriel, their owner, must lead them across the sky as a punishment for hunting on a Sunday. Legends of Gabriel Hounds may have evolved from flocks of night-flying geese, whose honks can sound like dogs barking.

Not all ghostly black dogs are evil, however. The Gurt Dog of Somerset is a friendly, protective beast. Mothers in the Quantock Hills once let their children play unsupervised as they felt the Gurt Dog would look after them. The dog also guides and defends travellers.

Various legends speak of benevolent black dogs. Manx folklore relates the tale of a fisherman who wanted to get to his boat, but met a black dog on the way who – however much the fisherman tried to dodge around it – refused to let him pass. The fisherman eventually gave up and returned home. That night, a terrific storm blew up that would have pulverised his ship. A number of tales have solo travellers passing through dark and lonely woodlands who suddenly find a black dog accompanying them. The dog doesn’t leave them until they exit the forest. The travellers later invariably find out that bandits have been watching them and would have murdered and robbed them if not for the presence of the dog. Tales of guardian black dogs seem to have become more common around 1900, perhaps showing the influence of late Victorian sentimentality.

Ghostly black dogs have been known to guard travellers in lonely woodlands. (Photo: Holy Stones and Iron Bones)

A benign black dog is said to have haunted a farmhouse near Lyme Regis, Dorset. The dog never caused any trouble, but one night the farmer got drunk and attacked the dog with a poker. He chased it into the attic, where the creature escaped by jumping straight through the ceiling. The farmer struck at the dog as it disappeared and – at the spot where his poker crashed down – he found a hidden hoard of gold and silver. The man used this loot to set up an inn – a bed and breakfast, called The Old Black Dog, claims to stand on its site today. The black dog still prowls a nearby lane – pet dogs wandering down this road have mysteriously vanished. Black dogs in Scotland are also believed to guard treasure. If you dare to move a standing stone near the village of Murthly in Perth and Kinross, you’ll uncover a treasure chest protected by a black dog.

Cannock Chase, a spooky tract of countryside in Staffordshire, is reputedly haunted by a number of black dogs, such as the Hednesford Hellhound and the wonderfully named Slitting Mill Bastard. Local folklore alleges Cannock Chase has also played host to UFOs, werewolves, big cats and even Bigfoot.

The sites of gibbets seem popular hangouts for black dogs. Such an animal has haunted Galley Hill, near Luton, Bedfordshire, since lightning set fire to a gibbet in the 18th century. In Tring, Hertfordshire, a chimney sweep was hung in 1751 for drowning a woman he suspected of witchcraft. His corpse was then suspended in chains from a gibbet. The sweep’s ghost is said to haunt the spot where the gibbet stood in the guise of a black dog and you can sometimes hear the clattering of his chains. The dog once appeared before two men in a flash of fire – the size of a newfoundland, it had blazing eyes and long fangs.

Black dogs also sometimes haunt tumuli. One has been sighted around the Six Hills, a group of Roman barrows in Stevenage, Hertfordshire – mounds, folklore asserts, the Devil constructed.

A particularly frightening black dog is the Welsh Gwyllgi – known as the ‘Dog of Darkness’ or ‘Black Hound of Destiny’. The dog – described as a huge mastiff or black wolf with noxious breath and burning eyes – appears to individuals after dark, especially on isolated roads. Glimpsing the dog is a prediction you’ll suffer a horrendous death.

Where Might Britain’s Black Dog Legends Come from and What Could Account for Them?

Though Britain has an especially high concentration of black dog legends, the menacing ghostly black dog is an archetype found in many regions of the world. Tales of phantom black dogs have been recorded in Belgium, France, Germany, the Czech Republic, the United States, Mexico, Central America and Argentina and more stories could probably be found of these spooky canines in other parts of the planet.

The archetype also seems an old one. The earliest-known written record of a black dog legend is from France – in 856 AD, one manifested in a church even though the doors were shut. The oldest document attesting to black dogs in England is from 1127. It describes a wild hunt that haunted the surroundings of Peterborough Abbey. The huntsmen ‘rode on black horses and black he-goats and the hounds were jet black with eyes like saucers and horrible’. It’s likely black dog legends go back quite some time before these sources, however.

Most black dog legends cast the beast as some sort of harbinger of death or messenger from the otherworld. The more sinister black dogs are associated with the Devil and hell; others are linked to tormented souls forced to conduct wild hunts. The dogs predict death for those who see them or – less commonly – guard people from such a fate, but in both cases the animals know the spectre of death is near. The connection with death could account for them haunting graveyards and gibbets. The black dogs’ deathliness is also emphasised by the fact some are headless and drag chains – both of which are general characteristics of ghosts.

The ability of black dogs to pass between the otherworld and this one might explain their manifesting at liminal spaces like crossroads and tumuli. Folktales describe ancient barrows as entrances to other realms and crossroads have long been seen as spots at which one reality might intersect with another. The ambiguous nature of the black dog is also expressed in its shapeshifting.

But why, we might ask, are dogs associated with death? This largely comes from their scavenging habits. Though dogs can certainly hunt, they often prefer to feed on carrion, a tendency that has likely linked them to decay and death in the popular mind. Another scavenger with similar folkloric associations is the raven – a bird notorious for banqueting on battlefields and haunting gallows and gibbets. This bird’s links with executions seem to have been a powerful factor connecting ravens in legend with the Tower of London. The colour black – in the case of both the black dog and the raven – is also symbolic, being a colour of death and mourning in Western cultures.

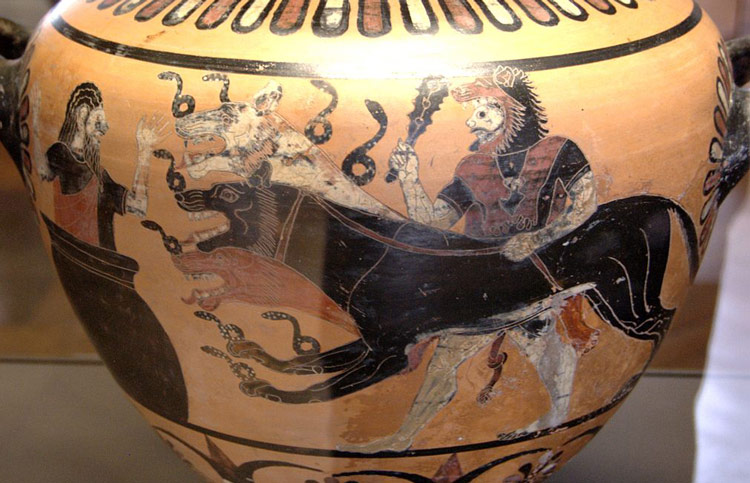

If we delve back beyond folklore and into mythology, we can also find dogs associated with death, the underworld, and liminal spaces and thresholds. The entrance to Hades is guarded by Cerberus, a multi-headed dog whose eyes – according to some accounts – flash with fire. The gate of the gloomy Norse underworld Hel is guarded by Garmr, a terrifying blood-bespattered wolf or dog. Some equate Garmr with Fenrir, the ferocious cosmic wolf who – by bursting out of his chains – will help usher in the Viking end times Ragnarok.

Vase showing Cerberus, the guardian of the Greek underworld – was he a prototype of the ghostly black dog?

In Welsh Myth, the Cwn Annwm are the hounds of the lord of the otherworld, Annwm. These dogs – rather than being black – are white with red ears. Celtic culture associated the colour red with death and white with the otherworld. Annwm leads his dogs in a wild hunt, especially at liminal ‘turning points’ of the year, such as Christmas and midsummer. To hear the dogs howling is a portent of death and the hounds are sometimes thought of as escorting souls to the next life.

Dogs have been domesticated for thousands of years and many of their traits can be found in black dog legends. Dogs can be companionable; they can work at useful tasks, protect humans and guard property; but – encountered under the wrong circumstances – they can be vicious and dangerous. The wolf has not been completely bred out of the species. All this probably helps account for the ambiguity and unpredictability of black dogs in folklore. How many of us would shudder, even today, if – walking alone on a remote, twilight path – we were to see a large, unaccompanied dog padding towards us or silhouetted, staring in our direction, down the road?

(This article’s main image is courtesy of the London Fortean Society.)

Speaking of greek mythology: Hellhounds were also the companion of Ecate (Hecate), goddess of boundaries, crossroads, witchcraft, ghosts, poisons ect.. Dogs were sacred to this specific deity and usually even sacrificed to her. Maybe that’s also one of the correlations between dogs and lost people and even this specific ghostly depiction of them as infernal beasts. Cerberus isn’t really a “hellhound”, yes the Ade is indeed the “greek hell” in a christian reading of the greek cosmology but Cerberus is just another dog-monster like others in the greek mithology (like Ortro, his brother) and put as a gatekeeper of Ade because of his monstrous appearance, violent behavior and dog attributes (fidelity and diligence) but still hellhounds/ghostly dogs existed as a separate creature in the greek mithology.

Thanks for your comment, deadlosh. I think Cerberus is more of a guardian of the underworld rather than a hellhound in the later Christian sense, but there might be some vague relation between the underworld guardians of Greek and Norse myth and later black dog legends. I’ll have to check out the differences between dog-monsters/hellhounds/ghostly dogs in Greek myth.

This is a fabulous ecapsulation of the black dog phenomonon, thank you very much! I agree with deadlosh that an honoury mention of cerberus might be nice as well as anubis; the dog headed god of the dead in ancient egypt. But I think it’s not entirely necessary and you’ve got just such a well of information here. I’ce been researching this phenomenon and this is by far the best article I have found with the most information. Wonderful work!

So glad you enjoyed my round-up of black dog folklore, Inkantress. Many thanks for your comment.

I believe that I had an encounter with a guardian black dog. I am happy to elaborate if anybody here is interested.

Hi Burt, sounds interesting! Please feel free to tell us about your encounter with the black dog.