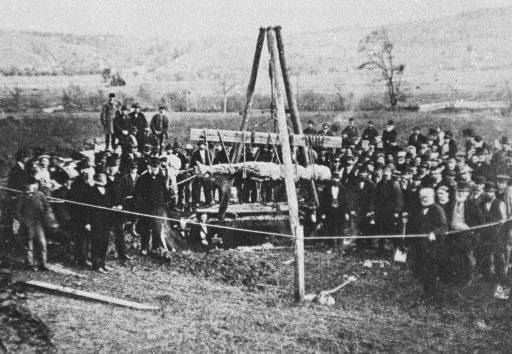

In 1869, workers digging a well behind a barn in Cardiff, New York State, made a bizarre discovery. They found what seemed to be the corpse of a 10-foot (three-metre) giant who’d been turned to stone.

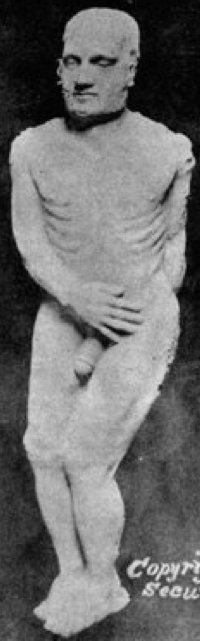

The labourers gawped at the colossus they’d uncovered. They could make out pores in his petrified skin, a ‘skin’ under which veins and arteries appeared to run. The giant boasted nails, nostrils, an Adam’s apple; an enigmatic half-smile was frozen on his face.

One workman blurted, ‘I declare some old Indian has been buried here!’

The Cardiff Giant – as the creature soon became known – would shake American society. His discovery would trigger a strange series of events, involving fiery preachers, competing conmen, rival freakshows, massive sums of money, arguing experts and thousands of ordinary citizens desperate to glimpse the stony colossus.

Some would even see the Cardiff Giant as evidence of the literal truth of the Bible. Genesis 6:4 states that, in ancient times, giants – known as Nephilim – stalked the earth.

Was the Cardiff Giant really a remnant from some superhuman, mythological past? Was he an elaborate hoax? Why were so many people – in an America hurtling into an age of railroads and skyscrapers, science and capitalism – keen to believe in this relic from the dawn of the world?

Let’s dig down and see what we can unearth about the Cardiff Giant.

The Giants of Ancient Times and Their Petrified Remains

‘They lie with the warriors, the Nephilim of old, who descended to Sheol with their weapons of war. They placed their swords beneath their heads and their shields upon their bones, for the terror of the warriors was upon the land of the living.’ Genesis 6:4

Most systems of myth make some mention of giants. Giants are usually seen as a bad lot – aggressive, violent, and representing unpredictable natural forces that the gods must subdue so order and civilisation can flourish. In Greek myth, the giants – offspring of the titan Uranus and earth mother Gaia – fought the Olympian Gods for control of the cosmos. In Norse legend, the ominous frost giants are predestined to defeat the gods in a terrifying conflict at the end of time, arriving for battle in a ship made from dead men’s nails.

It was, however, biblical giants that Victorian Americans were most concerned about. In Genesis, the Nephilim are the product of the ‘sons of god’ (sometimes said to be fallen angels) and the ‘daughters of men’. The children that sprang from these strange couplings are described as ‘the mighty men that were of old, warriors of renown.’ Later in the Bible, the Book of Numbers states of the Land of Canaan: ‘And there we saw the Nephilim, the sons of Anak … and we were in our own sight as grasshoppers and so were in their sight.’

The problem was that – in a world reeling from the spread of new scientific ideas – the Bible’s authority was under attack. Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species – published ten years before the Cardiff Giant was found – had shaken the faith and worldview of many.

But, for the more traditionally minded, there was hope. For some time, newspapers had been carrying reports of petrified humans – giants among them – that had supposedly been dug up across North America.

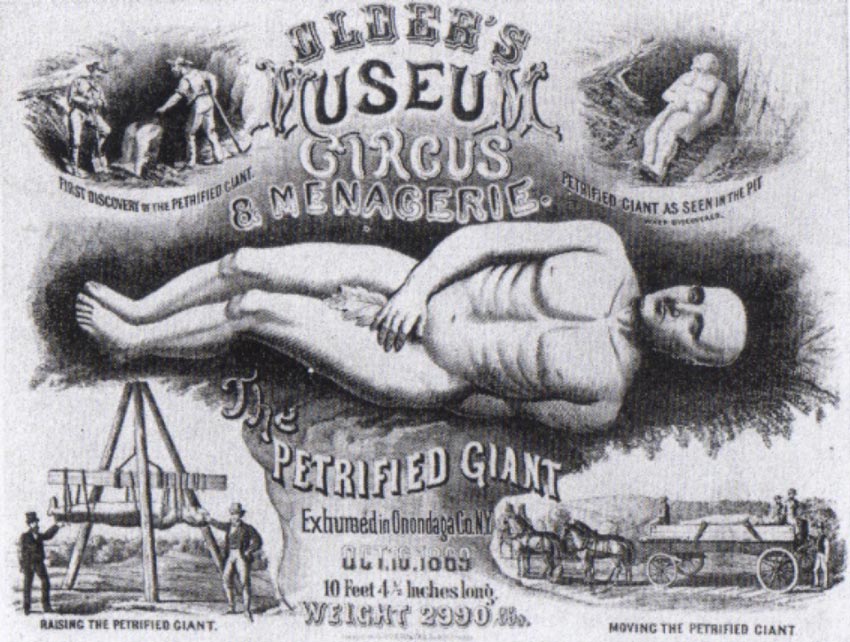

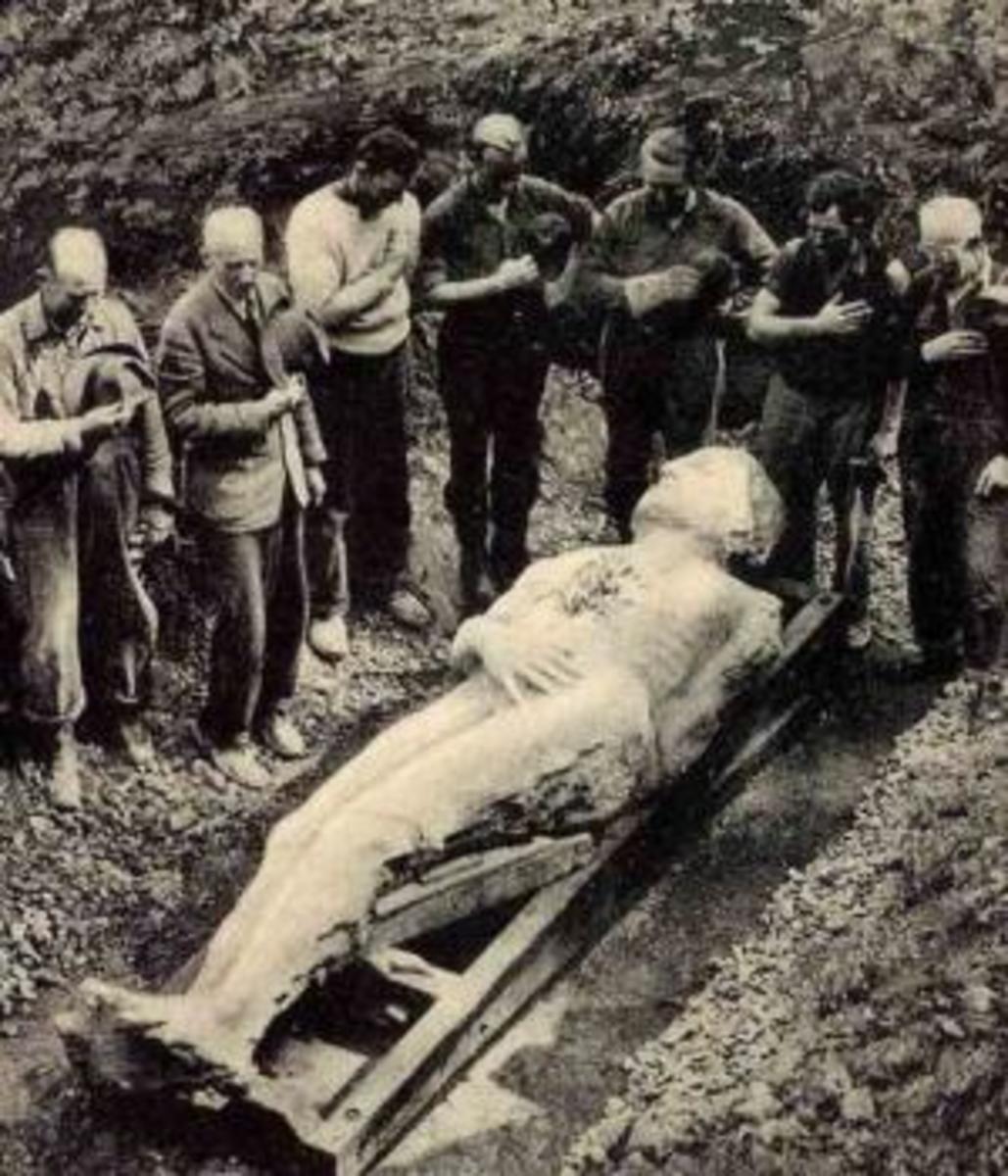

The Cardiff Giant is exhumed

Such articles – with their ‘rock-solid’ evidence of biblical Nephilim – could soothe Christian minds unsettled by new theories. Thanks to the Victorians’ mania for natural history, fossils were already a subject of fascination. If snails and fish and plants could be preserved in rock, many speculated, why not men and even giants?

And the American landscape did seem to oblige, by supplying occasional instances of ‘human petrification’. In 1858, the newspaper Alta California published a letter claiming a prospector had been petrified after drinking liquid found in a geode, a type of roundish hollow rock. In 1881, the New York Times reported that a Colorado man had dug up stones resembling human body parts, which – put together – formed the shape of a man 13 feet (3.96 metres) in length. In 1884, a petrified man – measuring seven feet four (2.25 metres) – was supposedly found on an Ontario farm. In Victoria, British Columbia, two farmers sinking a well were said to have uncovered a 12-foot (3.65-metre) giant, whose body was hard as flint and whose veins and ribs were visible.

Reports such as these cropped up in the papers from time to time, but with the Cardiff Giant there was no doubt that a body had been found, a body that would soon be on display for anyone who wished to view it. These remains seemed to offer the strongest proof yet that giants had once prowled the planet. As news of the Cardiff Giant spread and the public’s amazement grew, theologians and preachers rushed to proclaim the figure as undeniable evidence of the truth of Genesis.

The Cardiff Giant Sparks Wild Enthusiasm

It didn’t take long for the people of Cardiff – and those of nearby towns – to hear about the giant. The Syracuse Journal stated, ‘Men left their work, women caught up their children and babies, all hurried to the scene.’ It’s estimated that over 2,500 people saw the Cardiff Giant in the first week after his discovery. Railway companies put on extra trains to cope with the numbers flocking to the spectacle.

William Newell, the man upon whose land the Cardiff Giant had been found, soon put up a tent over the figure, charging 25 cents to see it. Wagonloads of eager visitors kept arriving so Newell upped the entry fee to 50 cents two days later. As excitement built, local newspapers proclaimed the Cardiff Giant ‘a singular discovery’ and ‘a new wonder’.

The Cardiff Giant becomes a popular attraction

The Cardiff area was already famous for its fossils – several important fish fossils had been found in a nearby lake – so it wasn’t difficult for many to believe the giant was an ancient human who’d been petrified in the local swamps.

Interestingly, Cardiff was also a centre of fiery religious revivals. The town is near the ‘burnt-over district’, where preachers thundered about hellfire and redemption during the Second Great Awakening (~1790-1850). Several religious leaders claimed God had appeared to them in the area, including Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism. This strange combination of scientific intrigue and religious fervour made Cardiff a fitting place for a relic of ancient humanity to have been unearthed.

The writer Ralph Waldo Emerson called the giant ‘astonishing’ and ‘undoubtedly ancient’. Others, while not believing the Cardiff Giant was a petrified man, put forward the idea he was an ancient statue. Well-known academics – such as New York geologist James Hall, the fossil expert Dr John F. Boynton and Rochester University professor Henry Ward – gave support to the statue theory, with Ward declaring the Cardiff Giant ‘the most remarkable object yet brought to light in our country.’

Was the Cardiff Giant Genuine?

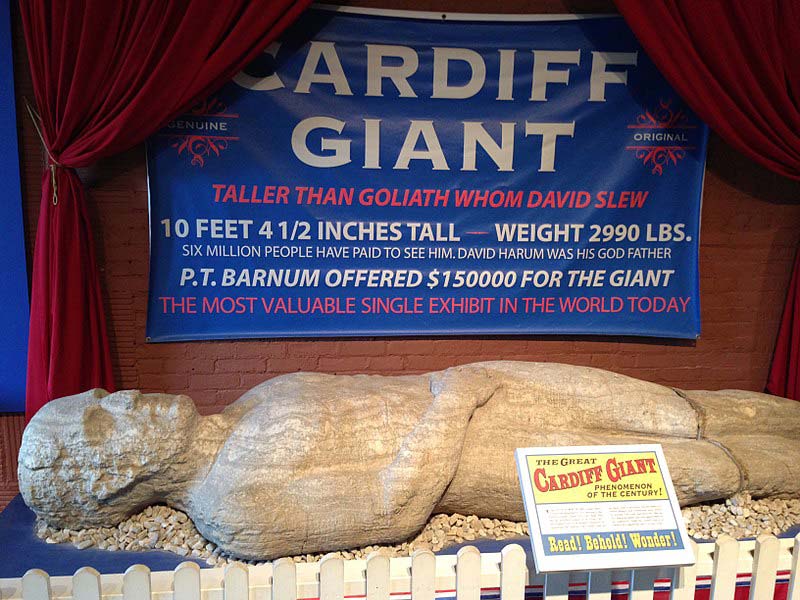

The Cardiff Giant

In 1867, George Hull – a tobacconist and atheist – got into an argument with a Methodist preacher while on a business trip to Iowa. Hull was exasperated by the preacher’s literalist interpretation of Genesis, especially his insistence that giants had once lived on the earth. Hull lay in bed later that evening mulling over the preacher’s notions and an idea began to form.

Hull hired men in Fort Dodge, Iowa, to quarry out a block of gypsum, 10-feet-and-4.5 inches (3.18 metres) long, with a weight of five tons. Hull told the men it would be used for a statue of Abraham Lincoln in New York. Next, Hull transported the block to Chicago, where he paid a German stonemason, Edward Burghardt, to carve it into the shape of a man. Burghardt was sworn to secrecy.

Hull and Burghardt poured acid on the giant to make him look suitably worn and weather-stained. They pricked his skin with needles to give the impression of pores, and sculpted nails, nostrils, an Adam’s apple and ribs. Lines unexpectedly appeared in the gypsum that resembled human veins. The giant was originally given hair and a beard, but Hull removed these when he learnt hair doesn’t petrify. In contrast to the fearsome reputation of biblical and mythological giants, Hull’s creation sported a mysterious half-smile, which would soon be charming the public.

In November 1868, Hull shipped the 2,990-pound (1356-kilo) giant by railway to the farm of his cousin, William Newell. By then, Hull had spent around $2,600 on his hoax, equivalent in modern terms to $48,000. The giant was buried on Newell’s farm and – 11 months later – Newell hired two labourers to dig a well, knowing all about the ‘incredible discovery’ they were set to unearth.

Capitalism and Ancient Myth Collide: The Cardiff Giant Becomes a Cash Cow

Newell was soon making good money as people kept streaming to Cardiff to pay their 50 cents to view the giant.

But despite the public’s enthusiasm, the Cardiff Giant attracted scepticism almost immediately. Geologists pointed out there had been no good reason for Newell to dig a well where the giant was discovered. A mining engineer viewing the figure caused a hubbub by announcing that gypsum would have soon decayed in the soggy soil of Newell’s farm. The Yale palaeontologist Othniel C Marsh only needed a glimpse of the Cardiff Giant to declare it ‘of very recent origin and a most decided humbug.’ Some churchmen, however, went on insisting the giant was a genuine Old Testament colossus.

Two women visiting the Cardiff Giant

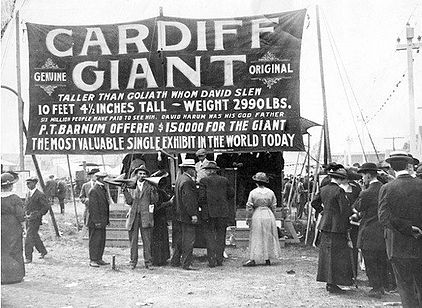

The controversy around the Cardiff Giant boosted its value. Hull sold his share in the giant for $23,000 ($445,000 in today’s money) to a syndicate headed by one David Hannum. The syndicate exhibited the giant in Syracuse, New York State. Here it drew such enormous crowds – with the railways again having to alter their schedules – that the showman and entrepreneur P.T. Barnum offered to buy the colossus for a cool $150,000.

And Then the Cardiff Giant Became Two

When his offer was refused, Barnum responded by making his own giant. He hired a man who somehow managed to cover the Cardiff Giant in wax, making a cast that was used to create a plaster replica. Barnum then exhibited his giant in his American Museum in New York City while proclaiming the other giant up in Syracuse was a fake.

Hannum sued Barnum for declaring his giant a hoax, but his case began to look less hopeful when the judge told Hannum a favourable verdict would depend on getting his giant to stand up in court and solemnly swear his authenticity.

The original giant, meanwhile, began to tour the country and soon arrived in New York, where it was exhibited just a few blocks away from Barnum’s replica. Even this fact, and increasing scepticism about both giants, did little to dim the public’s delight, with many New Yorkers still keen to go and see ‘Old Hoaxey’.

A poster advertising the Cardiff Giant

Barnum – whose museum exhibited real scientific artefacts alongside fakes such as ‘mermaids’ – played on this, issuing a leaflet stating, ‘What is it? Is it a statue? Is it a petrification? Is it a stupendous fraud? Is it the remains of a former race?’

In December 1869, Hull confessed everything to the press and in February the following year, the court declared that both giants were fake and that Barnum could therefore not be sued for claiming the first giant was a hoax. Public interest in the Cardiff Giant dwindled and the numbers visiting both giants plummeted.

The Strange Afterlife of the Cardiff Giant and Yet More Imitators

The Cardiff Giant was displayed at the 1901 Pan American Exhibition, where it was something of a flop. The giant was later bought by the Iowa publisher Gardner Cowles Jr, and used as a coffee table and talking point in his basement ‘rumpus room’. In 1947, Cowles sold the Cardiff Giant to the Farmers’ Museum, in Cooperstown, New York, a museum that seems to have become his final resting place.

The Cardiff Giant in his final resting place in the Farmers’ Museum (Photo: Wikiwand)

Barnum’s replica has ended up in Marvin’s Marvellous Mechanical Museum, an arcade of slot machines and entertaining oddities in Farmington Hills, Michigan.

Yet another copy of the giant can be found in Fort Dodge, Iowa – where Hull’s gypsum block was quarried – displayed in The Fort Museum and Frontier Village.

P.T. Barnum’s replica of the Cardiff Giant in Marvin’s Marvellous Mechanical Museum (Photo: Austin Dern)

The Cardiff Giant – probably due to its ability to slacken purse strings – inspired a number of imitators across America.

The Solid Muldoon – exhibited in Beulah, Colorado, for 50 cents a peek – was a giant made of clay, ground bones, meat, rock dust and plaster. Many suspected the Muldoon was another creation of George Hull, who’d now run through the fortune he’d made from the Cardiff Giant. Interestingly, Barnum was rumoured to have made an offer for the Muldoon, this time for $20,000.

In 1877, the owners of the Taughannock House hotel on Cayuga Lake, New York, created a fake petrified man that was conveniently dug up by workmen as the hotel was expanding. And in 1892, one Jefferson ‘Soapy’ Smith of Creede, Colorado, paid $3,000 for a ‘petrified man’, which he exhibited for 10 cents a ticket.

Perhaps most bizarrely, a ‘petrified man’ found in 1897 near Fort Benton, Montana, was proclaimed to be the corpse of Civil War general Thomas Francis Meagher, who’d drowned in the Missouri River 30 years previously. The ‘general’ was exhibited across Montana and displayed in Chicago and New York.

The Cardiff Giant has continued to haunt American popular culture. In Mark Twain’s A Ghost Story, the Cardiff Giant’s ghost appears in a Manhattan hotel room, pleading to be reburied. But, in a somewhat post-modern twist, the spirit is so confused that it haunts Barnum’s replica of itself. A computer named The Cardiff Giant featured in the TV series Halt and Catch Fire.

The giant even had a living human imitator, George Augur, a circus giant who worked for the Ringling Brothers. Billed as standing at eight feet (though he was more likely seven-and-a-half), George – who adopted the stage name The Cardiff Giant – performed in the big top with a family of Hungarian midgets, who formed a striking contrast to his towering stature.

What Does the Legend of the Cardiff Giant Tell Us?

The Cardiff Giant seems to me evidence of a collision of modern and ancient worlds: biblical literalism slamming up against science, developments in geology and evolution confronting legend, ancient myth hitting hard-faced capitalism, and the use of industrial techniques to fabricate a folkloric monster. With the Cardiff Giant episode, we can see the nightmares and obsessions of our ancestors entering modern culture through the portals of circuses, freakshows, short stories and 10-cent exhibitions.

The Cardiff Giant appeared at a time when the lines between myth, religion, science and entertainment were blurred. As Barbara Franco points out in her book The Cardiff Giant: A Hundred-Year-Old Hoax, people were interested in the emerging sciences, but few really understood them. There was less of a distinction between the serious and popular study of subjects. Victorian Americans attended carnivals, religious revival meetings, freakshows, and scientific exhibitions and lectures with much the same attitude – an attitude that demanded they be both educated and entertained.

With the growth of democracy and individualism, there was also the idea – like in our internet age – that autonomous individuals had the right to view the evidence and make up their own minds. Yet, paradoxically, one effect of the Cardiff Giant case – with the embarrassment the hoax caused to intellectuals and experts – was to encourage more rigorous expectations of science and a greater distinction between ‘armchair’ and professional approaches to research.

Monsters still haunt our modern dreams, even if they appear in more debased forms than those the ancient legends and holy scriptures clothed them in. The Cardiff Giant is not the only folkloric being to erupt into our modern world. Other examples include Glasgow’s Gorbals Vampire, the Manchester Mummy, the Highgate Vampire and London’s Spring-heeled Jack.

The American society of the late 1800s – hurtling into an age of industry and capitalism – couldn’t quite leave its old archetypes behind. On the brink of the 20th century – despite the growth of factories and skyscrapers, despite the ever-expanding frontiers of science – dark and ancient fears still plagued people’s minds.

Leave A Comment