In St Mary’s Church, in the village of Frensham, Surrey, the strangest object can be found. Propped up on a tripod, near the pews, beneath the arched windows, in among all the other fittings you’d expect in an English country church, stands what appears to be a witch’s cauldron.

There it is, a little battered, but looking as if a knowledgeable practitioner of magic could soon get a fire going and start brewing a potion in it. Authentically aged and well-used, it’s just the sort of cauldron you could imagine the Weird Sisters cackling around on Macbeth’s blasted heath.

But what’s an item many would associate with witchcraft doing in a place of Christian worship? Unsurprisingly, many legends have grown up around this incongruous object – a heap of intertwisted tales involving a chaotic collection of characters.

The cauldron has been linked to the Devil, Saxon chieftains, Celtic and Norse gods, a witch’s cave, burrowing monks, fairies, broomsticks, rustic peasant knees-ups, prehistoric burial mounds, healing waters and sacred wells. Let’s try to unknot this convoluted mass of myth and find out why this cauldron stands in St Mary’s Church, Frensham.

A landscape of woods and heathland surrounds the village of Frensham, which lies near the towns of Farnham and Guildford in Surrey’s commuter belt. (Photo: weesam2010)

Some Say the Frensham Cauldron Once Belonged to the Fairies

Near Frensham are three hills known as the Devil’s Jumps. A person climbing the highest of these – Stony Jump, formerly also called Borough Hill – would have once encountered an outcrop of rock crowning its summit. A deep crack scarred this rock and – if you whispered down into it – it was apparently possible to make contact with a colony of fairies that lived inside the hollow hill.

These fairies seem to have been a reasonably benevolent and human-friendly variety of the little folk, because they loaned out utensils to anyone who needed them. All you had to do was scale the hill, knock on the rock, whisper into the crack and tell the fairies what you wanted to borrow. A voice would then issue from deep within the hill, telling you when and where to collect the object and when it should be returned.

One day somebody asked to borrow a cauldron. He duly found the cauldron waiting at the appointed time and in the designated spot, but made the error of bringing it back late. Enraged, the fairies refused to accept it. They announced they would never again lend any implements to ungrateful humans and that night ‘the people saw a great fire’ though they later found no evidence any heathland had been burning.

The fairies inflicted a special punishment on the cauldron’s borrower. They cursed him to be followed by the cauldron wherever he went. The stands of its tripod morphed into legs and it pursued the man everywhere.

Driven into anxiety by having his every movement dogged by an animated cauldron, the man’s mental and physical health crumbled. He eventually sought sanctuary in St Mary’s Church, where he collapsed and died. The cauldron had, of course, followed him in there and so it remained in the church.

St Mary’s Church, Frensham, Surrey, said to house a ‘witch’s cauldron’ (Photo: Edward Simpson)

As the historian Keith Thomas shows in his Religion and the Decline of Magic, fairy lore was widespread in England in the early modern period and Middle Ages. And there are certain things about the Frensham area that may have especially linked the local landscape to fairies. Though fairies were often thought to inhabit the insides of hills, they were also frequently believed to live in burial mounds. Four such mounds stand on Frensham Common. In addition, Neolithic arrow heads are often found around Frensham. Known as ‘elf bolts’, such artefacts are seen as weapons of fairies in folklore.

Fairy legends associated with the burial mounds on Frensham Common may at some point have transferred themselves to Stony Jump (Borough Hill) or intermingled with existing tales connected to that landmark. One version of the cauldron story has the borrower knocking on ‘a great stone lying, of a length of about six feet’ across the mouth of a cave on Stony Jump. Though such barriers are a widespread feature of burial mounds, there’s no evidence such a stone has ever existed on Borough Hill. Local folklore also claimed that ‘some have fancied to hear music’ coming from the Borough Hill cave and music issuing from barrows is a common characteristic of fairy legends. Even the name ‘Borough Hill’ suggests a possible connection with burial mounds and therefore fairies. The term ‘borough’ can refer to burial mounds as well as to hills, ancient earthworks (also considered places of fairy habitation) and human settlements.

Round barrows on Frensham Common, Surrey – could they have contributed to local legends of fairies and cauldrons? (Photo: Simon Burchell)

Perhaps the fairy lore around Frensham was used to explain why such a strange object as a cauldron was kept in St Mary’s Church. We know this link had been made as early as 1673, when the antiquarian John Aubrey recorded the belief that ‘an extraordinary great cauldron or kettle’ in Frensham Church had been transported there by the fairies long ago. This idea seems to have persisted down the ages. It’s mentioned in Nathanial Salmon’s Antiquities of Surrey, published in 1736. A 1985 article in The Farnham Herald – entitled Condemned to Be Chased by a Three-Legged Cauldron – has a man recounting a version of the legend he heard in his 1920s boyhood.

But, alas, anyone wishing to climb Stony Jump today to whisper to the fairies would have little success, even if the fairies were still inclined to help us humans out. Stony Jump is now private property, its rocky outcrop has been flattened and a house has been built upon it. How the fairies have reacted to this indignity is not known.

The Frensham Cauldron, Mother Ludlam’s Cave, a White Witch and the Devil

According to some legends, it wasn’t the fairies who were responsible for placing the cauldron in Frensham Church, but a local ‘white witch’ – or folk healer – called Mother Ludlam. Mother Ludlam’s home was said to be Mother Ludlam’s Cave, located in a sandstone cliff above the River Wey in Moor Park, near Farnham, Surrey.

Mother Ludlam, like the fairies, lent out utensils to her neighbours. One version of the story claimed that anyone needing to borrow an item had to go to Mother Ludlam’s Cave at midnight, turn round three times and three times repeat their request. They also had to promise to return the article within two days. (The fairies were more liberal, sometimes allowing people to keep objects for a year.) Another take on the legend said people merely had to go to the cave and drop a coin into Mother Ludlam’s cauldron, after which they could borrow whatever implement they desired.

Mother Ludlam would sometimes even loan out the cauldron itself, the cauldron she used to brew her potions and cook her concoctions of healing herbs. In the simplest version of her legend, Mother Ludlam became enraged when somebody borrowed her cauldron but didn’t bring it back. The offender – terrified by the witch’s fury – took refuge in Frensham Church, which is where the cauldron stayed.

More elaborate accounts bring the Devil into the scenario. One story states the Fiend visited Mother Ludlam’s Cave in disguise and asked to borrow her cauldron. Mother Ludlam, however, spotted his hoofprints in some sand and refused his request. The Devil stole the cauldron and the witch set off in pursuit – according to some tales – bestride her broomstick.

As Mother Ludlam chased him, the Devil made three great leaps. Each time he touched the ground, he kicked up some earth, forming a small hill. These hills, the Devil’s Jumps, can still be seen today. The Devil dropped the cauldron – or kettle – on the last of these hills, which is why it’s called Kettlebury Hill or just Kettlebury. As the Devil fled, he landed one more time, forming the natural amphitheatre known as the Devil’s Punchbowl, a small valley close to Gibbet Hill.

The Devil’s Jumps, near Frensham, supposedly created by the Devil as he fled with Mother Ludlam’s cauldron. (Photo: Peter S)

After recovering her cauldron, Mother Ludlam placed it in St Mary’s Church, where it would be protected from Satan’s grasping claws.

The Mother Ludlam legend is recorded in an account written down in 1869 and also from an interview with a local lady who lived until 1937. Though the Mother Ludlam legend likely stretches back earlier than these dates, it seems the version with the fairies is the more ancient one and that later stories then linked the cauldron to Mother Ludlam. Could Mother Ludlam have been an interesting local character and herbalist whose fame later appended itself to an older tale?

The Devil’s Jumps and the Norse God Thor

There’s an alternative account as to why the three hills are known as the Devil’s Jumps. Apparently, the Devil would amuse himself by leaping between their summits. He did this so often he annoyed the Nordic god Thor, who hurled a huge stone at the Fiend, which became the rocky outcrop on Stony Jump.

It’s possible that the introduction of Thor into this whole tangle of myth is a romantic, early 20th century addition, but a nearby village does have the name of Thursley, suggesting a local connection with the god.

As for the Devil, tales of him adding features to the landscape and leaping around are commonplace in Britain. The Colwell Stone – a large chunk of limestone in the centre of Colwell, Cornwall – was apparently put there by the Devil. The Fiend is also said to have created the whole of the Cotswolds by tipping a wheelbarrow of earth upon the land. With regard to his leaps, he’s reputed to have sprung down from the spire of Newington Church, Kent, leaving a smouldering 15-inch footprint on a stone near the churchyard gate. At Marston Moretaine, Bedfordshire, he jumped down from the church before joining some lads in a game of leapfrog. A hole in the ground opened into which they all leapt and they were never seen again. Perhaps the Devil’s leaping abilities have lived on in later folkloric characters, such as the Victorian London demon Spring-heeled Jack. In Victorian times, the Fiend also got the blame for the Devil’s Footprints: a miles-long trail of hoofmarks in single file left in the snow across Devon in 1855, a trail that appeared to have been made by a hopping demon.

Unusual landscape features – like boulders dumped by glaciers and oddly shaped outcrops – often attract strange tales. Another one from Frensham states that there was once a boulder on one of the Devil’s Jumps that a person in need of any object – even a yoke for oxen – could approach. The person just had to touch the boulder, pray and promise to return the item. One day someone requested a cauldron, but – as the loaned implement was then kept in Frensham Church for too long – it couldn’t be given back and the boulder’s lending capabilities ceased. It’s not clear if this ‘boulder’ was thought to be the same chunk of rock Thor hurled.

Mother Ludlam’s Cave, Holy Wells and a Long History of Healing Waters

Mother Ludlam’s Cave, once home to her famous cauldron? (Photo: Weydonian)

The name Mother Ludlam’s Cave (also known as Mother Ludlum’s Cave and Mother Ludlum’s Hole) may have interesting origins.

Suggestions for its etymology include a Celtic term meaning ‘bubbling spring’, and the area around the cave is thought to have been home to a spring known as the Ludewell. The name may also derive from a Saxon king called Lud, who is said to have washed in the Ludewell’s waters to heal his wounds after a battle.

But – according to the writer of semi-legendary history Geoffrey of Monmouth (c. 1095-1155) – Lud (or Ludd or Llud) was a ruler of Celtic Britain and London’s founder. Lud is linked to the mythological Welsh figure Lludd (or Nudd) Llaw Eraint and the legendary Irish King Nuada. Both these characters are thought to have emerged from memories of the Celtic god Nodens, who – among his other attributes – was a god of healing. A temple to this deity is said to have stood near Ludgate in the City of London. (Geoffrey states this is where King Lud was buried. It’s not uncommon in myth for gods to be associated with earthly kings.)

It seems the Ludewell spring was thought to have medicinal properties. It could, therefore, have been regarded as a holy well by pre-Christian peoples and perhaps linked with the healing god Nodens (aka Lud). This association could have survived in the name Mother Ludlam – also a healer – and become mingled with memories of a much later herbalist.

All this is, of course, speculation. Other possible origins for the cave’s name are the Saxon words for ‘meeting place’ and ‘loud’, perhaps in reference to the stream that ran from the Ludewell. But it’s interesting to think that some sort of connection with healing may have lingered around the cave from Celtic times through to Saxon warriors bathing their wounds through to an early modern herbalist brewing her potions in a cauldron.

The cave’s associations with pure and curative waters do seem to have continued into the Christian era. Nearby, on the banks of the River Wey, stand the picturesque ruins of Waverley Abbey. Walter Scott visited the ruins while researching his biography of Jonathon Swift and was enchanted – this experience may have inspired the title of his famous book Waverley. The abbey also inspired Arthur Conan Doyle’s novel Sir Nigel.

Waverley Abbey, Surrey, one of whose monks enlarged Mother Ludlam’s Cave (Photo: Antony)

Founded in 1128, the abbey appears to have relied on the stream issuing from the Ludewell for its drinking water. However, this source dried up around 1218. In response, a monk called Symon searched for a new source, probably expanding Mother Ludlam’s Cave in the process, until he found – according to the Annals of Waverley Abbey – a ‘living spring’. With ‘much difficulty and invention, labour and sweating’ he enlarged it and – through an ingenious system of channels – brought its waters to the abbey. The monks christened the new spring St Mary’s Well. The original Ludewell probably started off in a cavern – a little above Mother Ludlam’s Cave on the cliff – known as Father Foote’s Cave (see below).

The esteem in which the monks held their new well – which probably boasted the same health benefits as the Ludewell – can be seen in the name they gave it (St Mary’s is also the name of Frensham Church). Healing wells in the Middle Ages were often named after saints and some became sites of pilgrimage.

St Mary’s Well had healing associations in quite modern times. The political radical William Cobbett (1763-1835) recalled that in his boyhood Mother Ludlam’s Cave contained ‘basins to catch the little stream’; ‘iron cups, fastened by chains, for people to drink out of’; and ‘seats for people to sit on, on both sides of the cave’. So it seems at that time the cave was a venue for people to imbibe medicinal waters. After revisiting the cave in 1825, however, Cobbett complained it was in a dire condition, with the seats torn up, the basins and cups gone, and ‘the stream that ran down a clear paved channel now making a dirty gutter.’

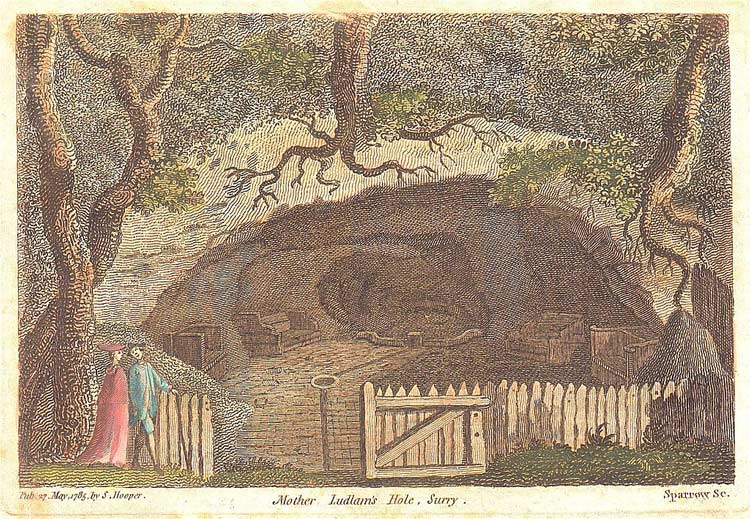

A depiction of Mother Ludlam’s Cave from 1785

What has all this, we might ask, to do with the cauldron in Frensham Church? The Mother Ludlam story was likely an invention to explain the presence of that unusual object in St Mary’s, but it’s worth pointing out that cauldrons have long had connections to healing, religion and magic. In Celtic times, cauldrons were crammed with votive offerings and left at holy sites. A story of King Arthur has him travelling to the Welsh Otherworld to steal a cauldron that could only be heated by the breath of nine virgins and would never cook food for a coward – a possible early source of the Holy Grail legends. A cauldron possessed by the Welsh hero Bran the Blessed is said to have had the power to revive dead warriors cooked in it overnight, though in the process they lost the ability to speak. In Frensham, can we see some tangled links between mythical notions of cauldrons, religious and magical sites, and caves and springs associated with healing?

The Gundestrup Cauldron (made between 200 BCE and 300 CE) – a silver vessel decorated with Celtic motifs discovered in a Danish bog. (Photo: Rosemania)

Mother Ludlam’s Cave was made into a grotto, probably during the 18th century, and in Victorian times an ironstone arch was added to its entrance, perhaps indicating a revival in the attraction of its medicinal waters after the desolation William Cobbett witnessed. In 1962, a roof collapse reduced the cave’s length from 200 feet (61 metres) to 192 (58.5 metres) and another collapse occurred in 1976. Today the cave is a roost for a number of bat species, with efforts being made to encourage the rare greater horseshoe bat to take up residence. Perhaps Mother Ludlam’s Cave can continue to be a place of healing, but for nature rather than humans.

Father Foote’s Cave

Father Foote’s (or Fooke’s) Cave – a small cave located above Mother Ludlam’s – also has a story attached. An old man named Foote – after staying for some time at the Seven Stars Inn in Farnham – is said to have dug the cave out of the cliff and made it his home. One day in 1840, Father Foote was found lying next to a stream, obviously unwell, and was taken to Farnham Workhouse, where he died. His last words were: ‘Take me to the cave again!’

It’s likely the cave is older than this, however. The cave may well have been the source of the original Ludewell, though it is now completely dry. The cave apparently has side alcoves that look manmade, perhaps suggesting it too was once frequented for its waters. I’m tempted to think that the ‘Father Fooke’ figure might have arisen from a folk memory of a saint or hermit or even water spirit once associated with the cave and the healing waters of Ludewell, whose legend was perhaps grafted onto stories of a much later person. I cannot, however, claim any evidence for such an assumption.

Father Foote’s Cave, a little above Mother Ludlam’s Cave on the cliff and maybe the source of the Ludewell. (Photo: BabelStone)

So Where Did the Cauldron in Frensham Church Really Come from?

As entertaining as the above stories are, I think we can discount the tales of the cauldron being borrowed from fairies or being placed in the church by a white witch after she’d snatched it back from the Devil. The cauldron’s origins are really quite simple and practical.

The cauldron was almost certainly used to brew ale for weddings, church festivals and other social occasions in the Middle Ages. The cauldron is made of hammered copper and is nineteen inches (48 centimetres) deep and three feet (91 centimetres) in diameter – a common design for medieval ale making.

Though it may seem strange today, churches were once venues for drinking parties – festivities known as ‘parish ales’. Parish ales had a number of subcategories – the church ale (which raised money from the sale of food and beer to maintain the church building), the leet ale (which took place on the manorial court day, a kind of village fete), the lamb ale (held at lamb sheering time), the Whitsun ale (held at Whitson) and the bride ale (a wedding feast that raised money for a newly married couple).

In addition to drinking beer, these events included plenty of feasting, as well as dancing, games and sports, activities that took place either in the churchyard or on the village common. Most churches would have had a cauldron to brew the ale and the profits from selling the beer were a vital source of income.

The poet Francis Beaumont (1584-1660) wrote:

The churches must owe, as we do all know,

For when they are drooping and ready to fall,

By a Whitsun or church ale up again they shall go,

And owe their repairing to a pot of good ale.

During the Reformation (1517-1650), parish ales aroused the disapproval of Protestant leaders, who disliked drunkenness and frivolity being associated with the Church. Though parish ales were never banned, they became less common, often being limited to Whitsun. In some places, the custom gradually faded away while in others parish ales continued in some form until quite modern times.

At Frensham, the parish ale custom probably declined, but the cauldron remained in the church. Wondering what the strange object was, locals are likely to have created stories, stories that meshed with existing tales of fairies, witches, the Devil’s shenanigans and healing wells.

The chroniclers who wrote down these legends – while charmed by them – quickly dismissed such yarns. Writing in 1673, John Aubrey could clearly see the cauldron was ‘an ancient utensil used by the villagers in their love feasts.’ In his Antiquities of Surrey (1736), Salmon refuted the suggestion the cauldron had been brought by fairies, insisting the object was ‘used for the entertainment of parishioners at the weddings of poor maids.’

Despite its non-mystical – though I hope not uninteresting – origins, what fascinates me is how such a complex knot of folklore has been woven around the Frensham cauldron, pulling in tales from various eras, cultures and traditions. Around this kitchen implement stories of Nordic gods, Saxon heroes, sacred wells, Victorian paupers, folk healers and Celtic myths have all been entangled, as well as – of course – legends of the Devil and his fondness for landscape architecture. It’s incredible how such a humble device has managed to get enmeshed in such diverse tales, in such a ravel of imagination and myth.

(This article’s main image – showing Mother Ludlam’s cauldron in Frensham Church, Surrey – is courtesy of BabelStone)

Leave A Comment