In London and New York, stand two ancient and strikingly similar obelisks. Close to Waterloo Bridge, the London monument towers beside the Thames while in New York what seems to be its twin looms over Central Park. Both covered with Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, these structures reach the height of seven-storey buildings and weigh well over 200 tons. Both go by the same name – Cleopatra’s Needle – and were chiselled out of red granite by thousands of workers upon the orders of an all-powerful pharaoh almost 3,500 years ago. This article will trace the bizarre story of how these Ancient Egyptian artefacts came to be rehomed in England and America. It will also highlight the weird legends, the frightening folklore, the terrifying curses, the occult ceremonies said to be associated with these displaced monoliths.

The London Cleopatra’s Needle – having survived a deadly and storm-thrashed sea journey – has indeed accrued the most macabre legends. There are claims that Cleopatra’s Needle emits an occult power that encourages passers-by to fling themselves into the Thames. As well as being a favoured spot for suicides, this allegedly cursed artefact is said to contain the spirit of an Egyptian pharaoh and to have been the focus of a magical ritual by Aleister Crowley. The homeless and destitute who congregate on the Embankment will go nowhere near it, mocking laughter is said to echo over the water at night, and a character with scaly skin and a tall headdress has been seen diving into the Thames beside it without causing a ripple or splash.

Cleopatra’s Needle in London towers beside the Thames (Photo: Mrs Ellacott)

Cleopatra’s Needle in New York was the focus of rituals involving thousands of Freemasons. Hauled across the Atlantic and dragged through the city thanks to the most remarkable feats of engineering – and thanks to the interventions of America’s richest man – the needle is said to stand in a weird Masonic alignment with New York’s other obelisks. The London Cleopatra’s Needle, it’s claimed, is also positioned as part of a network of occult sites – arranged in the shape of a pentagram some reckon, as a diagram of the eye of the Egyptian god Horus insist others.

Cleopatra’s Needle in New York City’s Central Park (Photo: Ingfbruno)

Below is a story of colonial competition, of the jostling of rising and falling empires. It’s a tale of Masonic schemes to transmit age-old messages encoded in hieroglyphs; an account of eerie time capsules, World War I bombs, the spirits of dead sailors, and outpourings of dark energy said to have influenced none other than Jack the Ripper. It’s a story of how Cleopatra’s Needles crossed seas and oceans and how they continue to assert their weird and baleful power upon our minds even today.

The Early History of Cleopatra’s Needles – Sun Gods, Huge Granite Columns and Cleopatra’s Roman Lovers

Around 1450 BC, Pharaoh Thutmose III decided to commemorate his 30 years on the throne by ordering two obelisks to be sculpted from enormous, single blocks of red granite. These blocks were quarried at Aswan – close to the Nile’s first cataract – then somehow transported over 500 miles to Heliopolis, which now lies in the northern suburbs of Cairo. Though the Nile was definitely involved in moving these massive monuments, no one is quite sure how Thutmose managed to shift them over such a long distance. Thutmose had hieroglyphs inscribed in a single column on each of the four sides of Cleopatra’s Needles and the obelisks were then erected outside a temple to the sun, with each guarding one side of its gateway. (In Ancient Egypt, obelisks symbolised the rays of the sun god Aten-Ra.) Around two centuries after Thutmose had set the obelisks up, Pharaoh Ramesses II added more hieroglyphs to celebrate his military triumphs – arranging his text in two columns running down the obelisks’ sides, flanking Thutmose’s carvings.

The obelisks remained outside the temple of the sun for more than 1,400 years, although at some point they seem to have toppled over and lain buried in sand for half-a-century. In 12 BC, the Romans moved them over the-not-inconsiderable distance of 130 miles to Alexandria. (Again, the Nile was involved and – again – we don’t know exactly how they did it.) There they were erected outside the Caesareum – a temple built by Cleopatra in homage to her Roman lovers Julius Caesar and Mark Antony. (Hence, the obelisks’ connection with Egypt’s most famous – and last – pharaoh.) The monuments stayed at the Caesareum for almost two millennia, but the obelisk that would become the London Cleopatra’s Needle once again tipped over and was covered by sand. This turned out to be fortunate as it meant its hieroglyphs were protected from the eroding effects of the desert’s sand-blasting storms. But the ambitions of new and rising empires meant the long stay of Cleopatra’s Needles outside the Caesareum would not prove permanent.

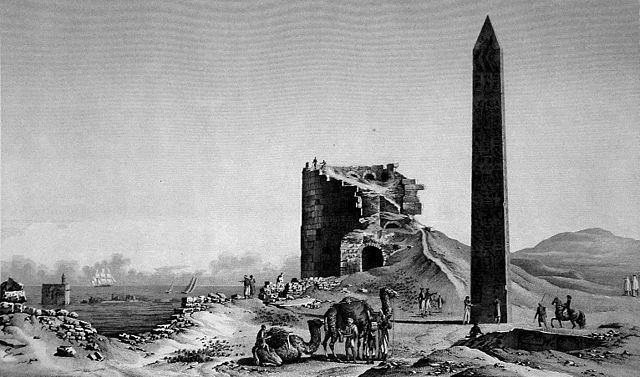

A sketch of the ruins of the Caesareum from 1798. The Cleopatra’s Needle that ended up in New York City is upright. The London obelisk can be made out in the foreground, mostly buried in sand.

Cleopatra’s Needle Is Readied for Transport to London – Battles, Egyptomania, Rival Obelisks and the Beginnings of ‘the Curse’

In 1798, Napolean launched an invasion of Egypt, an act that began decades of struggles for control of the country between the British, the French, the fading Ottoman Empire that had ruled Egypt for centuries, and Egyptian leaders who wanted to establish a powerful independent state with colonial territories of its own. These conflicts would involve battles, revolts and diplomatic manoeuvrings. Additionally, when Napolean invaded Egypt, he brought with him around 160 ‘savants’ – scholars, linguists, archaeologists and scientists – to investigate that intriguing land of temples, statues and tombs. There were also around 2000 artists and engravers, who created images of these monuments. As the research of the savants and the sketches of the artists filtered back to Europe, they sparked a phenomenon known as Egyptomania, in which the continent went mad for all things Ancient Egypt. Egyptian designs influenced furniture and jewellery, Egyptian themes cropped up in novels and plays, and pyramid-shaped mausoleums appeared in Europe’s graveyards. Egyptomania also led to an enthusiasm for real Egyptian objects, with mummies, artefacts and even obelisks ‘acquired’ from the country. It’s against this backdrop of colonial power struggles and Egyptomania that the story of Cleopatra’s Needle plays out.

In 1819, the viceroy and de facto ruler of Egypt and Sudan – an Albanian named Mohammed Ali, who’d wrested significant power from the Ottomans – bestowed (the reclining) Cleopatra’s Needle on the British as a diplomatic gift. This present was intended to celebrate British triumphs over the French at the Battle of the Nile (courtesy of Lord Nelson) and the Battle of Alexandria (under Sir Ralph Abercromby). The prime minister, Lord Liverpool, expressed gratitude for the gift, but the Brits were faced with the problem of how on earth to transport the 224-ton, 69-foot megalith the 3880 nautical miles to England. With no solutions becoming apparent, the obelisk was allowed to stay in its age-old position in the Caesareum’s ruins. As time drifted on, however, certain people in the British establishment became increasingly unhappy at the thought of such a prestigious monument lying unappreciated under its centuries of sand.

Coloured photograph of Sir James Edward Alexander in 1860. Some years later he would strive to bring Cleopatra’s Needle to London.

In 1867, General Sir James Edward Alexander – a Scottish writer, traveller, soldier and Egypt enthusiast – visited Paris, where his competitive instincts were inflamed by his observation that the French already possessed an Egyptian obelisk. In the Place de la Concorde, there towered a magnificent, yellow-granite, 75-foot monolith, boasting a weight of over 250 tons. This obelisk – from Luxor – had been gifted by Muhammed Ali in 1833, possibly as part of a strategy of using Egypt’s wealth of ancient artefacts to play Egypt-obsessed European nations off against each other. Tolerating far less delay and dithering than the British, the French had shipped their megalith home and had unveiled it in October 1836 in a ceremony officiated by King Louis Phillipe in front of 200,000 people.

The Luxor obelisk in the Place de la Concorde, Paris (Photo: Craig Booth)

Alexander was determined that London should have an obelisk to match the one reared up in Paris. Accompanied by the British Consul General Edward Stanton, Alexander met the Khedive of Egypt, Isma’il Pasha. Isma’il was a visionary leader, but – under his ambitious rule – Egypt had slid into debt. Modernisation programmes – encouraging industrialisation, urbanisation, agricultural improvement and the expansion of education – as well as costly wars with Ethiopia had bankrupted the treasury. The European powers had used these pressures to wring concessions from Isma’il Pasha, with the British and French assuming control of most of Egypt’s finances and acquiring Egypt’s shares in the Suez Canal. Against such a background, it’s likely that Isma’il felt he had little choice but to go along with Alexander’s determination to get Cleopatra’s Needle out of Egypt. Incidentally, if Cleopatra’s Needle is cursed, Isma’il Pasha may have been one of its first victims. He would be swiftly removed from power – at France and Britain’s behest – in 1879. He went into exile, eventually being offered sanctuary by the Ottomans, where he ended up virtually a state prisoner in an Istanbul palace beside the Bosphorus. He died in 1895, due to – according to Time magazine – the effects of trying to down two bottles of champagne in one swig.

Isma’il Pasha, the Khedive of Egypt and Sudan. Was he the first victim of Cleopatra’s Needle’s curse?

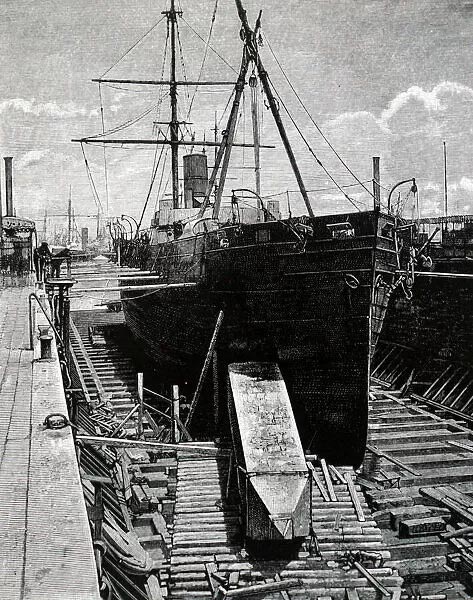

Alexander now needed to work out a way to shift the colossal obelisk and to find the money to fund its voyage. Help for both these matters came through a friend, a stupendously wealthy surgeon, dermatologist and – yes – fellow Egypt nut called Sir William James Erasmus Wilson. In 1877, Wilson agreed to contribute the massive sum of £10,000 (almost one million in modern money) to finance the monolith’s journey. While trying to figure out how this journey would be accomplished, Wilson turned to a friend: a locomotive and railroad engineer and – again – Egypt obsessive named Mathew William Simpson. Simpson, who worked for the Khedive, came up with the idea of digging the obelisk out of the sand then cocooning it in an iron tube, 16 feet wide and 92 feet long. The plan was that, once constructed, this cocoon would become a cylinder-shaped boat, named the Cleopatra. The Cleopatra would be tugged by a steamship – the Olga – all the way to England.

1830s lithograph of the Caesareum. The New York Cleopatra’s Needle stands in the background while the London needle is partly buried in sand.

As Simpson – due to his obligations to the Khedive – was unable to devote himself to the work, he recruited another engineer – John Dixon – to finish off the design. John kitted out the Cleopatra with a rudder, keels, mast, bridge and cabin. He had the Cleopatra built in pieces in England, at the Thames Iron Works. These pieces were shipped out to Egypt then fitted around the obelisk under the direction of Waynam Dixon, John’s brother. Finally, the Cleopatra was ready for its journey, waiting to be hooked up to the Olga, which would be under the command of one Captain Booth. At this point – it seems – the obelisk was ready to show its fury and discomfort at being hauled away from its native land.

Ferocious Storms, Death at Sea and a Strange Time Capsule – Cleopatra’s Needle’s ‘Cursed’ Voyage to London

The strange procession of the Olga and Cleopatra – with the latter commanded by one Captain Carter and crewed by Maltese mariners – sailed through the Mediterranean with little incident. But as the ships were passing through the notoriously temperamental Bay of Biscay, an incredible storm blew up. With the rain smashing down, the wind battering the boats and the waves unrelenting and mountainous, Captain Booth became convinced the Cleopatra would sink, taking the Olga down with it. He decided to attempt a rescue of the Cleopatra’s crew before cutting the ropes and letting Cleopatra’s Needle drop to the ocean bed in its metal sarcophagus. A smaller boat, manned by six sailors, set out from the Olga to pick up the Cleopatra’s men. However, the raging sea overwhelmed the smaller boat and its sailors were lost. Eventually, the Olga managed to draw up alongside the Cleopatra and save its five crew members. Captain Booth then ordered the tow ropes cut and the Cleopatra was carried away on the waves, with all those present assuming the tubelike ship with its cursed cargo would sink. Five days later, however, a Spanish fishing craft spotted an odd-looking boat bobbing on the now-much-calmer sea. It was the Cleopatra, miraculously undamaged. Mathew Simpson’s innovative design had somehow survived all the Bay of Biscay could hurl at it. A Glasgow steamer – the Fitzmaurice – towed the Cleopatra to the northern Spanish port of Ferrol. The Anglia – a paddle tug – was then sent to haul the Cleopatra to Britain.

Cleopatra’s Needle Being Brought to England, by George Knight, 1877. The Olga and Cleopatra are depicted struggling in rough seas.

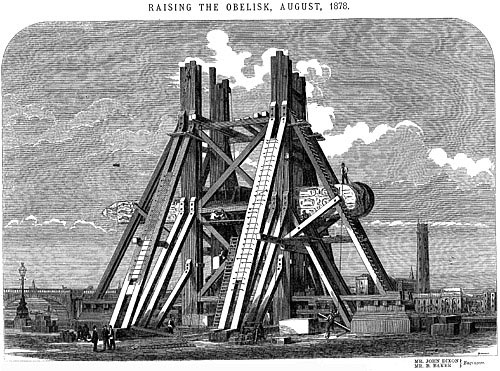

On 21st January, 1878, the ships reached the Thames. Shoreside crowds clapped and cheered, cannons fired salutes and all the schoolchildren in the estuary town of Gravesend were given the day off. There was some debate about where Cleopatra’s Needle would go – a wooden model of the monolith had previously been put up outside the Houses of Parliament, but this location was deemed unsuitable. Eventually, the Embankment was chosen – the curious decision being made to erect an archaic monument on a symbol of modernity and progress: the elegant riverside walkway had recently been constructed to conceal an enormous sewer, the central part of an innovative underground network devised by Joseph Bazalgette. On 12th September 1878, Cleopatra’s Needle was hoisted into position. Two Victorian sphinxes – designed by English architect George John Vulliamy – were set up on each side of the obelisk, facing inwards towards it (more on this strange orientation below). The Embankment was also lined with Egyptian-style benches, boasting camels and winged sphinxes as part of their metalwork.

An illustration from the journal ‘Engineering’ showing Cleopatra’s Needle being erected on London’s Embankment

As the obelisk was lowered into place, a time capsule was entombed beneath it. The capsule’s contents could hardly have been more Victorian. It contained a gentleman’s lounge suit and 10 illustrated newspapers, including that day’s edition of The Times. The capsule also held Bradshaw’s Railway Guide (again, a thrusting achievement of Victorian progress), an assortment of women’s dresses and cosmetics, Queen Victoria’s portrait, children’s toys, Bibles, collections of coins, a razor (more on this later), and 12 photographs of what were considered exceptionally beautiful women (these pictures are said to have been chosen by Captain Carter). Other items included a baby’s bottle, some of the cables that had hauled Cleopatra’s Needle upright, a map of London, an account of the monument’s dramatic journey to England, a three-inch bronze miniature of the obelisk, a box of cigars and a selection of hairpins. As we shall see, certain elements of this ensemble have helped fuel the mythos of a haunted Egyptian megalith and its occult influence on the darker side of life in the capital.

The Creepy Mythology of Cleopatra’s Needle – Strange Beings, Eerie Laughter, Weird Alignments, Jack the Ripper and Aleister Crowley

A certain amount of paranormal lore is associated with Cleopatra’s Needle in London. Such lore has cropped up in ghost anthologies, on websites, and in literature, poetry and film. It is, indeed, sometimes difficult to separate what might be considered ‘genuine folklore’ from internet memes and the outpourings of artistic imaginations, but this section will attempt some sort of summary of the notions that have grown up around London’s ancient obelisk.

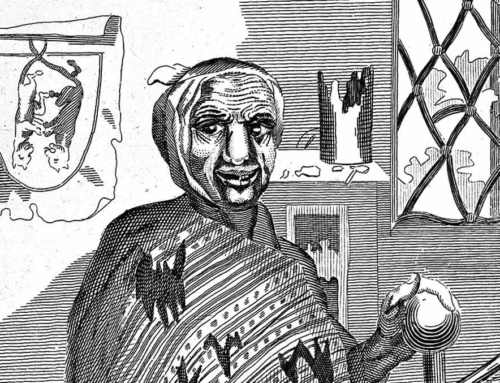

Perhaps the most famous piece of folklore linked to Cleopatra’s Needle is chronicled in the book Haunted Waters (1957) by the ghost-hunter Elliott O’Donnell. O’Donnell starts his tome by claiming: “I have often felt when in proximity to some rivers and pools as if the water possessed a strange, magnetic influence and attraction, as well as sensing the presence of a spirit, sometimes friendly and sometimes evil and inimical.” He feels this is especially true of the Thames, which “should assuredly be haunted, for no river in Great Britain has witnessed more murders and suicides.” O’Donnell recounts how, in the early 1890s, he would wander along the Embankment and chat to “the wretched down-and-outs, homeless and hopeless” who could be found “on nearly every seat.” Some of these homeless people confided that “they had felt a ghostly presence, urging them to end their miserable existence by jumping into the river.” O’Donnell goes on to say that the “spot where Cleopatra’s Needle stands was well-know to be haunted. None of the outcasts would venture near it. Two of them told me that one night they saw a tall, nude, shadowy figure, with a peak-shaped head and a body covered with what looked like scales, suddenly appear by the needle, wave a long arm at them and leap over the wall into the river. They said that they sometimes heard unearthly groans and hellish, mocking laughter in the river.”

According to the folklorist Steve Roud in his London Lore, a peculiar London myth concerns the siting of the sphinxes at the needle’s base. The two Victorian sphinxes – decorated with hieroglyphic inscriptions reading “the good god, Thuthmosis III given life” – are facing inwards towards the needle, rather than outwards as they would have been in Egypt. It is a widespread belief, Roud states, that they were “positioned inwards to protect London from its occult power”. If there’s any truth in this legend, the other folklore linked to Cleopatra’s Needle would suggest this precaution hasn’t worked.

In London, Cleopatra’s Needle is flanked by two Victorian sphinxes – were they positioned facing inwards to contain its occult power? (Photo: DaringDonna)

London legend states the monument is a popular location for suicides. Twice, apparently, policemen were approached by an agitated woman claiming someone was about to leap in the river. The officers ran towards the obelisk, only to see the very same woman plunge into the water. It’s also claimed that the apparition of the naked diving man began appearing shortly after Cleopatra’s Needle was set up and that it is in fact the spirit of one of the sailors who perished in the Bay of Biscay. Unearthly screams heard around the monument are said to issue from the lost sailors. An inscription on the needle’s pedestal commemorates the seafarers who drowned.

One of the large Victorian sphinxes positioned on either side of Cleopatra’s Needle, London. (Photo: Colin Smith)

An even more outlandish legend insists that the spirit of Rameses II is trapped inside the obelisk and that this has meant a powerful curse has been placed on London. This assertion is linked to the infamous British magician Aleister Crowley. Allegedly, one night, Crowley conducted a ritual to liberate the soul of Rameses. The ceremony involved the feeding of animal blood to a human skeleton. I’m not sure how Crowley would have got away with dragging a skeleton through the capital’s streets or how a skeleton could be fed with anything, but Crowley’s procedure is said to have failed. It’s claimed the laughter heard around the obelisk is Rameses mocking Crowley’s attempt.

Another tale attests that in 1880 a young woman, Mrs Davis, was walking along the Embankment when she felt herself pulled against her will towards Cleopatra’s Needle. As the force dragged her closer, terrifying laughter rang out, she lost all control over her legs and hurled herself into the Thames. A vagrant rescued her, but while recovering in hospital she suffered nightmares in which she was tormented by a tall red-robed woman with black almond-shaped eyes. The woman would open her mouth, exposing fang-like teeth, before the skin and flesh were torn from her face. Another incident some claim was caused by the obelisk’s curse is easier to verify. During World War I, a bomb exploded close to Cleopatra’s Needle, with its shrapnel pitting the plinth and scarring one of the sphinxes. Following the War, this damage wasn’t mended. It was felt the scars were part of the obelisk’s story and – some would say – evidence of its curse.

Hieroglyphs on Cleopatra’s Needle. Does this London obelisk imprison the spirit of a pharaoh? (Photo: Man vyi)

A curious piece of lore relates to the time capsule embedded beneath Cleopatra’s Needle. Among other objects, it contains – if you recall – pictures of attractive women and a razor. It’s been asserted that the positioning of these items under the occult monolith sent waves of evil energy into the capital that encouraged the crimes of Jack the Ripper. While such a notion might seem far-fetched, the obelisk has made it into artistic depictions of this sinister episode in London’s history. In Alan Moore’s graphic novel From Hell, Jack the Ripper is Dr William Gull, a high-ranking Freemason and physician to the Royal Family. Gull states: “Few symbols match this stone in its potency … carved fifteen hundred years before Christ’s birth and raised at Heliopolis by Thotmes, etched with hieroglyphic prayers that Atum, Egypt’s Sun god, might increase his sovereignty.” Gull also remarks on the “Daguerrotypes of our epoch’s most lovely women … and a razor”. Gull places the needle within a pattern of sites around the capital charged with dark mystical energy. The Ripper argues that if one were to draw lines connecting such sites – which include Hawksmoor churches (some boasting their own obelisks), Daniel Defoe’s obelisk tomb in Bunhill fields, the Tower of London with its macabre history and St Paul’s (apparently, previously, a temple of Diana) – they would make up a … pentagram. The film version of From Hell (2001) has Ian Holme, as the Ripper, informing a victim in his coach about the six men who died bringing the obelisk from Egypt before murdering her.

Indeed, a number of writers and psychogeographers have embedded the needle as a central point in London networks of occult power. In his poetry collection Lud Heat, Iain Sinclair positions the needle as part of an arrangement of burial grounds, sacred hills, suicide ponds and Hawksmoor churches. (Nicholas Hawksmoor, nicknamed ‘the Devil’s architect’, was a Freemason fond of decorating his churches with ‘pagan’ symbols such as pyramids, mausoleums and – yes – obelisks.) The lines linking these sites form several shapes, including a triangle (or, if you like, a pyramid), a pentagram and a diagrammatic representation of the eye of the Egyptian god Horus. Sinclair writes, “There is a subsystem of fire obelisks: St Luke, Old Street, and St John, Horsleydown. They form an equilateral triangle, raised over the water, with London’s true obelisk – ‘Cleopatra’s Needle’.”

Let’s now move on to consider the Cleopatra’s Needle in New York, which – as we shall see – is also not lacking in occult significance nor in theorists eager to place it within systems of dark power in that metropolis.

Egyptian-style benches on London’s Embankment – evidence of Egyptomania? (Photo: Robin Sones)

Cleopatra’s Needle Comes to New York – America’s Egyptomania, Nautical Adventurers, Cannonballs and Freemasons

In New York’s Central Park, behind the Metropolitan Museum of Art, stands an artefact that at first looks somewhat incongruous. On a hillock – known as Greywacke Knoll – is a red granite obelisk covered in faded hieroglyphs. Weighing in at 250 tons (even its pedestal weighs a hefty 50), the obelisk is officially the oldest outdoor manmade structure in New York. This object – forming a strange backdrop to the park’s lycra-clad traffic of cyclists and joggers – reaches a height of 68 feet. It would have appeared even more striking when first set up in 1880, when few buildings in New York were that tall.

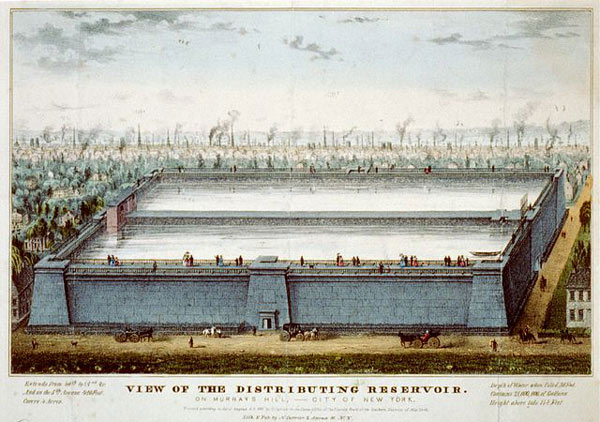

The process by which this monument came to be in this location is a story that in some ways mirrors the transportation of its twin obelisk to London. For New York – and American society in general – was experiencing its own version of Egyptomania. Some of the city’s more outlandish tombs – and even some of its prisons – had been built with Egyptian-influenced designs. The 50-foot granite walls of the Croton Reservoir – completed in 1842 – had been constructed in an Egyptian style. Around 1878, when London claimed its obelisk, New York was mushrooming in size and gaining in importance, with the Industrial Revolution and immigration firing its growth. As the prime city of an ambitious emerging empire, New York felt it needed its very own artefact from an impressive empire of yore. And, as with the London needle, this would be achieved courtesy of a determined and obsessive military officer, his influential backers, a very rich patron, some astounding feats of engineering, and a daring voyage.

An 1842 Lithograph of the Croton Reservoir – a sign of New York City’s Egyptomania?

How this version of Cleopatra’s Needle came to be in New York is outlined in an excellent 2020 episode of the Bowery Boys podcast. The podcast tells us that procuring the obelisk became the passion project of several wealthy men, but it particularly came to motivate one Colonel Henry Honychurch Gorringe. Gorringe was an intriguing character, much of whose life was bound up with both mythology and the sea. As a boy, he was shipwrecked then rescued from the coast of India. He served in the Union Army during the Civil War and by the beginning of the 1870s had got a job at the US Hydrographic Office, in which he produced maps of coastlines and drew nautical charts. Gorringe had numerous adventures at sea and at one point became convinced he’d rediscovered the mythical land of Atlantis. In the mid-1870s, he ended up in Alexandria, where he first beheld the twin set of Cleopatra’s Needles at the Caesareum. Perhaps knowing the recumbent obelisk had been promised to the British, Gorringe started to form ideas regarding its still-upright sibling. He began to agitate for the up-and-coming nation of the USA to claim its own gargantuan Egyptian artefact.

Henry Honychurch Gorringe in 1883 – did he fall victim to the curse of Cleopatra’s Needle?

He was far from the only American with such an ambition. The country’s growing self-confidence and the liberal dose of Egyptomania the young nation had ingested had led many to a conviction that they must match their European rivals and show them that New York was truly one of the globe’s foremost cities. With more than a hint of sarcasm, one newspaper commented, “It would be absurd for the people of any great city to hope to be happy without an Egyptian obelisk. Rome has had them this great while and so has Constantinople. Paris has one; London has one. If New York was without one, all those great sites might point the finger of scorn at us and intimate that we could never rise to any real moral grandeur until we had our obelisk.”

Gorringe was a Freemason, and this too would motivate him to acquire one of the Cleopatra’s Needles for New York. The Freemasons – a mysterious and influential secret society – had begun as guilds of stonemasons who worked on medieval cathedrals. Freemasons tend to be fascinated by the doings of ancient civilisations, by arcane emblems, and by what one might call the occult. Hence, it’s unsurprising they’re keen on Ancient Egypt – the ancient civilisation par excellence, with its mysterious hieroglyphs, intriguing religion, and powerful magical and metaphysical traditions. Also, the Egyptians had been experts in architecture and working in stone. When examining Cleopatra’s Needle, Gorringe discovered what he thought were ancient Masonic signs and seems to have persuaded himself that these hieroglyphs were attempts of Ancient Egyptian Freemasons to send messages to the Masons of the future. Gorringe, therefore, became convinced he had to get the obelisk over to New York to make its teachings available to America’s Masons.

Gorringe teamed up with Elbert Farman – the US Consul to Egypt – and they persuaded the Khedive to offer them Cleopatra’s Needle. With Egypt suffering deep financial problems – and eager to improve trade with the USA – the Khedive had little choice but to acquiesce. However, there was still opposition to Gorringe’s desire to remove the monolith. Britain and France objected to the upstart Americans acquiring an obelisk and discovered an eagerness to preserve Egypt’s heritage, lobbying the Egyptian authorities not to allow the artefact to go. In addition to this, the Egyptians themselves were growing more concerned about the carrying off of their inheritance. Demonstrations were organised and angry editorials appeared in newspapers. To top it all, an Italian man came forward claiming to own the land on which Cleopatra’s Needle stood – he was quietened by a threat from Gorringe to sue.

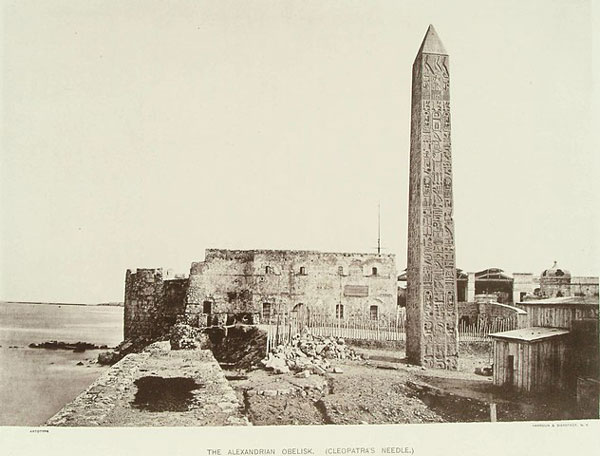

The Cleopatra’s Needle that would go to New York City still upright in the Caesareum in 1880. Its twin obelisk had already been removed to London.

Another potential source of friction had a more American tone. There was the possibility of debates in Congress, debates with the potential to delay the acquisition of Cleopatra’s Needle for years. An arrangement was therefore contrived by which the obelisk was directly gifted to the City of New York, thereby bypassing the threat of lengthy and tortuous disquisitions. The only problem remaining was how to facilitate and fund the transport of the monument, especially now that New York was expected to come up with the cash. Raising such a sum wasn’t guaranteed to be easy. The torch-bearing-arm of the Statue of Liberty was around that time exhibited in Madison Square Park, in an attempt to revive the stuttering campaign to generate the money to assemble the rest of the figure. However, as far as Cleopatra’s Needle was concerned, assistance soon arrived. The railroad magnate – and America’s richest man – William Vanderbilt stepped in and donated $100,000 (well over $3 million in modern money). Vanderbilt – a Freemason – helped select the site on which the obelisk would stand. Greywacke Knoll was chosen as Vanderbilt didn’t want the magnificent monolith overshadowed by growing city.

The challenge now was how to shift the obelisk and get it over the Atlantic to New York. Vanderbilt invited proposals on how this could be done and in August 1879, Gorringe was granted the commission. Gorringe first built a long wooden crate. After encasing Cleopatra’s Needle in this vast coffin, he used hydraulic jacks and various devices to lower it. The next problem was how to get the obelisk and its box to the Nile. Gorringe came up with a clever solution – he laid out a track of cannonballs and rolled the crate over them. Gorringe had bought an old Egyptian postal ship and reinforced its hull – and it was onto this ship he had Cleopatra’s Needle loaded. The monument’s pedestal and the stairs leading up to it were also hoisted on board. Unlike the disastrous voyage of Cleopatra’s Needle to London, the sea journey to New York was mostly hassle-free. On July 19th 1880, the postal ship with its ancient freight arrived off New York’s Fire Island.

Cleopatra’s Needle being loaded onto the modified postal ship to begin its voyage to New York City. It was slid onto the boat via a specially created portal in the hull.

The next day, a pilot boat guided the ship to Staten Island, where it passed through the quarantine station. Given the all-clear, the boat sailed up the Hudson River and docked at 23rd Street. New York had been ardently anticipating the artefact’s arrival, and while the boat was docked, 1700 people per day came aboard to gaze upon the monument. But even though Cleopatra’s Needle had been successful transported to New York, there was still the logistical issue of how to get it across the city to Central Park. The decision was made to first move the pedestal. The boat sailed further upriver to 51st Street, where a crane offloaded the 50-ton base onto a carriage. 32 horses dragged it through the city, with the carriage’s wheels carving deep grooves into the road due to the weight of its burden. The pedestal was, however, successfully put in place in Central Park, with the city now in even more of a ferment about its ancient acquisition. This would only be heightened when New York’s Masons put on a spectacular demonstration of reverence. Masonic mythology attaches great importance to the idea of cornerstones and the brotherhood were determined to welcome this very special foundation stone to their town.

Strange Masonic Rituals, Weird Occult Alignments and a Miniature Cleopatra’s Needle on a New York Grave

On October 9th 1880, a solemn procession of over 9,000 Masons and members of the Knights Templar paraded up 5th avenue to Central Park, with many clad in black clothes, tall hats, white gloves and aprons. A crowd of 50,000 lined the route. After the Masons arrived at the pedestal, a grand ceremony was conducted. Grain – symbolising plenty – was tipped over the stone. Next, the Grand Senior Mason poured on wine – symbolising joy – before his junior poured on oil, representing peace. The Grand Marshal then walked to each side of the platform and said: “In the name of the Grand Lodge of the State of New York, I now proclaim the cornerstone of this obelisk – known as Cleopatra’s Needle – duly laid in ample form.” On every side of the base, he recited these words three times, after which the mass of assembled Masons clapped their hands thrice. Grand Master Anthony then made a speech, all about the Ancient Egyptians and their pyramids and how they had the power to predict the future.

However, the Grand Master didn’t go as far as Gorringe in claiming a connection between Egypt’s ancient inhabitants and modern Freemasons. According to The New York Times: “The most remarkable part of the Grand Master’s address was that in which he disclaimed any Masonic origin for the hieroglyphics found upon the obelisk and this was a part of his oration, coming from such high Masonic authority, that could not have been edifying to those persons who have found – as are professed to believe – evidences of the existence of the Masonic Order at the time this obelisk was first erected.” Gorringe and others, as The New York Times implied, must have been gutted to hear the Grand Master’s words.

As for Cleopatra’s Needle itself, first the boat sailed to a dock on 96th Street, where the obelisk was floated from the ship catamaran-style on pontoons. To move the monument to its place in Central Park, Gorringe hit upon another ingenious idea. He had the obelisk rolled on railway-like tracks, with workers continually taking up the lengths of track behind and positioning them again in front of the monolith as it made its stately way through the city. In this manner, Cleopatra’s Needle covered approximately a block a day, taking 40 days in total to reach its destination. The most challenging part of the journey was when the obelisk had to get across the real railroad tracks of the Hudson River Railway. However, this railroad was part of a Vanderbilt-owned firm. One order from the tycoon halted the trains so the obelisk could lumber over the tracks. On January 5th 1881, Cleopatra’s Needle arrived at Greywacke Knoll.

The vast edifice was then kept suspended above the base, awaiting a ceremony set for January 22nd during which Gorringe himself would lower it onto its plinth. Gorringe had completed all the calculations, but remained anxious in case something might go wrong on his big day. So, on the night of January 20th, he crept into Central Park with a band of collaborators. They did a midnight test run, during which Gorringe was relieved to observe everything would be all right. On January 22nd – despite sub-zero temperatures – thousands of New Yorkers watched as the obelisk was manoeuvred into the position it still occupies today. As in London, a time capsule was placed beneath. Among other items, it contained the American Declaration of Independence, a set of military medals, and a guide to Egyptian and Masonic symbols.

Cleopatra’s Needle remains a popular attraction in Central Park, New York City (Photo: King of Hearts)

Since that time, Cleopatra’s Needle has remained a much-visited tourist site. The monument’s looming presence in the centre of New York helped fuel American Egyptomania into the 20th century, when the craze for all things Egyptian was again boosted by the British archaeologist Howard Carter’s discover of Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922. It seems the needle’s position outside the Metropolitan Museum of Art has had a galvanising impact on the Met’s collection. Perhaps not willing to be outdone by European museums, the Met financed expeditions to Egypt between 1906 and 1936. The Met boasts a phenomenal collection of Ancient Egyptian artefacts, including the Temple of Dendur. An exceptionally holy site seen as home to the gods, the temple was rescued from the rising waters of the Aswan High Dam and reassembled in the Met in the 1960s.

Questions, though, remain about the positioning of Cleopatra’s Needle. As early as 1923, newspapers were pointing out that the obelisk isn’t in exact alignment with the sun. (Egyptian obelisks have traditionally also functioned as sun dials.) It’s been argued, however, that this is no mistake and that a different – possibly Masonic – alignment has always been intended. According to the website Forgotten New York, there are three obelisks in Manhattan, though the other two are significantly younger than Cleopatra’s Needle. One of these monuments – found in the graveyard of St Paul’s Chapel – was constructed in the 1830s to commemorate Thomas Addis Emmet, an Irish lawyer and revolutionary and Attorney General of New York State. Although a cube-shaped chamber lies under the obelisk, Emmet isn’t interred there. Instead, he was buried at St Mark’s Church in the Bowery and later reburied in Ireland. The third obelisk – in Worth Square, at the junction of 25th Street, Fifth Avenue and Broadway – marks the resting place of General William Jenkins Worth (a powerful Freemason). This obelisk – which dates to 1857 and stands close to the Flat Iron Building – reaches 51 feet and is the second oldest monument in New York. All three obelisks, it’s claimed, align perfectly at 29 degrees east of north, with General Worth’s marking the line’s midpoint. Just one block away from the Worth Obelisk is … New York’s Masonic Hall and Grand Lodge. The reader must use their judgement to decide whether this is all a coincidence, a bizarre Masonic code or some sort of occult psychogeography.

The Worth Monument in New York City. This obelisk stands in alignment with Cleopatra’s Needle and the obelisk of Thomas Addis Emmet (Photo: Jim Henderson)

This section of the post would, however, be incomplete without mentioning at least one other obelisk. In 1885, Henry Honychurch Gorringe died at the age of just 43 as a result of injuries received when either trying to alight from or board a moving train. The more superstitious might see the curse of Cleopatra’s Needle in Gorringe’s demise – a curse expressed in the irony of Gorringe meeting his end courtesy of the invention that had made so much money for the man who’d financed the obelisk’s transport. Moreover, 1885 was the year in which Gorringe published his book Egyptian Obelisks, which mainly explored his acquisition of Cleopatra’s Needle for Central Park. However, Gorringe’s friends did not seem to perceive the dark shadow of the obelisk in his death. Gorringe was buried in Rockland Cemetery, Sparkhill, New York State. His memorial stone declares: “his crowning work was the removal of Cleopatra’s Needle from Egypt to the United States, a feat of engineering without parallel.” In 1886, his friends erected a replica of Cleopatra’s Needle over his grave. The unveiling ceremony drew 500 people and was widely reported in the press. The monument – decorated with Egyptian-style cartouches and with an illustration showing how Gorringe raised and lowered the needle – stands at over 25 feet and is of white granite. It cost $25,000 dollars (around $840,000 in today’s money) and – like the original obelisk in Central Park – it stands on its own knoll, from where it overlooks the Hudson River.

The replica of Cleopatra’s Needle in Rockland Cemetery, Sparkhill, New York State, on Gorringe’s grave (Photo: John T. Chiarella)

Why might these Strange Legends Have Grown up around Cleopatra’s Needles and Might the Obelisks Be Returning to Egypt?

Along with Egyptomania, there was a general idea that Egyptian artefacts were cursed. Thus, all the legends of cursed mummies inhabiting the museums and disturbing the private collectors of North America and Europe. One legend, for example, concerns an artefact known as the Unlucky Mummy that ended up in the British Museum. Said to be the remains of a priestess or princess called Amen-Ra, the Unlucky Mummy was held responsible for illnesses and deaths, and for actions as outlandish as haunting London Underground stations via secret tunnels, sinking the Titanic and starting the Second World War. It’s perhaps inevitable that an Ancient Egyptian object as imposing as Cleopatra’s Needle would generate tales of curses and vengeful ghosts. The London Cleopatra’s Needle especially, given its traumatic voyage to England, fitted into the ‘cursed object’ narrative. Hence the legend of the sphinxes trying to deflect its occult power. Though there seem to be less stories of ghosts and curses linked to the New York obelisk, we could ask whether the elaborate Masonic ceremonies that prepared the plinth for the monument’s arrival were not also intended to abate its paranormal influence. As non-Masons, I suppose, we can only speculate and never know.

A frequent suggestion for this association of unquiet spirits, unruly occult powers and potent curses with Egyptian artefacts is guilt over colonial plunder and exploitation. And how could these artefacts – the obelisks ripped from their temples, the mummy cases with their mournful eyes and affectingly human faces gazing accusingly across millennia – not be offended by being carried across seas and oceans to cold, far-off lands? The story of Cleopatra’s Needles is very much the story of militarism and empire. These monuments to Egyptian imperial might, crowing in hieroglyphs of military victories, were unsurprisingly sought out by later empires to celebrate their conquests and triumphs. Carved on the base of the London obelisk is:

“This obelisk

Prostrate for centuries

on the sands of Alexandria

was presented to the

British nation A.D. 1819 by

Mohommed Ali, Viceroy of Egypt

A worthy memorial of

our distinguished countrymen

Nelson and Abercromby”

Britain and France – as well as batting for territory and influence in Egypt – also battled for its artefacts, the larger and more prestigious the better. As America was beginning to feel its status as the new and rising empire on the block, it inevitably wanted an obelisk of its own.

We might question, however, if Cleopatra’s Needles will always remain in Central Park and beside the murky Thames, with its tidal rise and fall perhaps a modest imitation of the mighty fluctuations of the Nile. Concern has been voiced about the condition of the artefacts in their foreign homes. The American needle especially is somewhat worn, with its hieroglyphs quite faded. Already blasted by the sands of the Libyan Desert – unlike its London cousin it wasn’t protected for centuries by lying under sand in the Caesareum – it has suffered from New York’s harsher climate, with its hotter summers and colder winters than London. There was also a disastrous attempt to renovate it in 1885, when it was covered in gasoline and 700 pounds of granite were chiselled away, a process that probably damaged or removed a good few hieroglyphs. In 2011, the needle was inspected by Zahi Hawass – the Minister of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities – who penned a letter declaring: “If the Central Park Conservancy and the City of New York cannot properly care for the obelisk, I will take the necessary steps to bring this precious artefact home and save it from ruin.” Though the London obelisk is in a somewhat better state, a comment from Hawass in 2018 suggested he was also less than impressed with its condition: “I went to see it yesterday and I was ashamed … If they don’t care, they should return it.”

The hieroglyphs on the Central Park Cleopatra’s Needle have become worn thanks to the New York climate, acid rain, air pollution and misguided attempts at renovation (Photo: Captain-tucker)

For now, however, the obelisks are likely to remain in position and these imported monuments will doubtless continue to form a central part of the networks of myth, folklore, imagination and foreboding that run through both cities. It’s as if the monoliths are immense pins holding in place these strange threads of energy and power. Or, as Jack the Ripper puts it in From Hell: “They call it Cleopatra’s Needle. He who’d wield it would the BEST of tailors be, to do its work, increase the Sun God’s sovereignty … encoded in this city’s stones are symbols thunderous enough to rouse the sleeping Gods submerged beneath the sea-bed of our dreams.”

This article’s main image shows Cleopatra’s Needle in London. (Photo: Colin Smith)

Leave A Comment