Late at night on 5th October 1869, a group were gathered around a graveside in London’s Highgate Cemetery. As workmen dug down into the grave, a bonfire burned, providing an eerie flickering light and keeping away at least some of the night’s cold. Several respectably dressed men, among them a doctor and lawyer, watched the labourers. The firelight would have revealed distaste and sorrow on most of the faces present, along with a nervous fear of any members of the public realising what they were up to. The men, however, knew they had to exhume the body the grave held. They felt they were doing a service not only to a friend, but also to the cause of literature and art. Soon enough, there came the dreadful – yet longed-for – scraping of shovels on the coffin lid. The casket was manoeuvred and hauled up from where it had lain for the last seven years.

The coffin contained the body of Lizzie Siddal, the wife, model and muse of the Pre-Raphaelite painter and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Siddal, after years of poor health, drug use and psychological distress, had died on 11th February 1862, at just 32 years-of-age. As Lizzie had awaited burial, Rossetti – overcome by grief, tormented with guilt – made an impassioned gesture. He placed a book of his poems – the sole copy of his verses – in her casket. Rossetti wrapped the book in Lizzie’s long, striking, ginger hair; winding the tresses he adored, that he’d so often painted, that had drawn him to Lizzie Siddal in the first place, around and around the volume. This sacrifice enacted, the heartbroken Rossetti permitted his poetry – along with the woman he loved – to be lowered into the earth.

But seven years on, Rossetti changed his mind. Eager to publish a book of poems, and knowing some of his best work lay interred with his wife, Rossetti allowed himself to be persuaded Lizzie Siddal should be exhumed. Though Rosetti wasn’t at the disinterment – he couldn’t bear to be – his business agent Charles Augustus Howell would later describe to him the most astonishing scene.

After Lizzie’s coffin had been levered out of the grave, it was time to open the casket. A shudder likely went through the group as the ominous sound of a spade striking at the lid echoed across the night-time necropolis. But, when that lid came off, all – according to Howell – were amazed. Rather than the skeleton or rotting corpse they’d been bracing themselves to see, Lizzie Siddal was almost perfectly preserved and still beautiful. A kind of phantom glow added to her pallid charms and – most incredibly – her hair had grown during the seven years she’d been under the earth. The splendid red hair filled the coffin – yards of it glimmered in the firelight. So tightly wrapped was the book in the wonderous locks that they had to be cut before it could be freed. The book was then handed to the doctor, whose job was to disinfect it, making sure no diseases would pass from the grave to the living. (The lawyer was there so it could be clearly stated there’d been no foul play.)

I can imagine all those present – the labourers sweat-coated despite the cold night, the huddle of gentlemen – staring, for a moment, at the beauty they’d unearthed: at that pale – yet corruption-defying – face and, most of all, at the mass of fiery hair. But this morbidly serene image didn’t, apparently, last long. Thanks to the air coming into contact with Siddal’s corpse, she began to decompose and was hurriedly reinterred.

This exhumation marks a fascinatingly morbid chapter in the long and complex relationship between Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Lizzie Siddal, a relationship that would go on – in a strange way – well beyond Siddal’s death and even disinterment. It would haunt Rossetti to his own grave. It’s a tale of art and poetry; of love and neglect; of drugs and disaster; of sex and adultery and bohemian living and the manufacture of myth. It’s a story involving all kinds of strange – and often less than respectable – characters. But is this story – and even the exhumation that was perhaps its most dramatic episode – exactly what people have long perceived it to be?

Keep reading for tales of peanut-flicking prostitutes, of window-cleaning elephants and affectionate wombats, of furious attacks from morally outraged critics, of the origins of literary vampires, of bodies found with throats slit and coins in their mouths, and of some of the most tragic and talented artists the Victorian era knew.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti – the Passionate and Rebellious Young Artist Finds His Way

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti (he’d later invert his name in honour of the Italian poet Dante Alighieri) was born in London on May 12th 1828. His father, Gabriele Rossetti, was an Italian political refugee, who’d fled his homeland following a failed uprising in 1820. A professor of Italian at King’s College, Gabriele also wrote literary criticism and Romantic poems. Rossetti’s mother, Francis Polidori, was from an Anglo-Italian family, which also had literary connections – her brother, John William Polidori, had served as Lord Byron’s personal doctor and had penned the first vampire novel. Rossetti’s sister Christina would become a well-known poet, his brother William a critic and his sister Maria a novelist. In this artistic and intellectual ambiance, Gabriel (as his family called him) was at first home schooled, being immersed in Shakespeare, Dickens, Byron, Walter Scott, Arthurian legend, medieval poetry and the Bible. He’d later attended King’s College School in the Strand.

Descriptions of the young Rossetti ranged from ‘self-possessed, articulate, intelligent and charismatic’ to ‘ardent, poetic and feckless’. At first – like all his siblings – he yearned to be a poet, but also showed interest in painting and was especially obsessed with medieval art. Following four years at a drawing school, Rossetti – aged 17 – enrolled in London’s famous Royal Academy. He soon, however, found himself hating its academic and conservative approach, despising the prissy landscapes and portraits of glossy animals and pretty young women it encouraged artists to churn out. Rossetti – who was gathering a reputation as a Romantic free spirit – didn’t react well to any form of discipline and that included the ideas of rigorous training set down by Academy’s influential former president Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-92). Rossetti found the prospect of spending laborious years copying ancient statues simply horrifying.

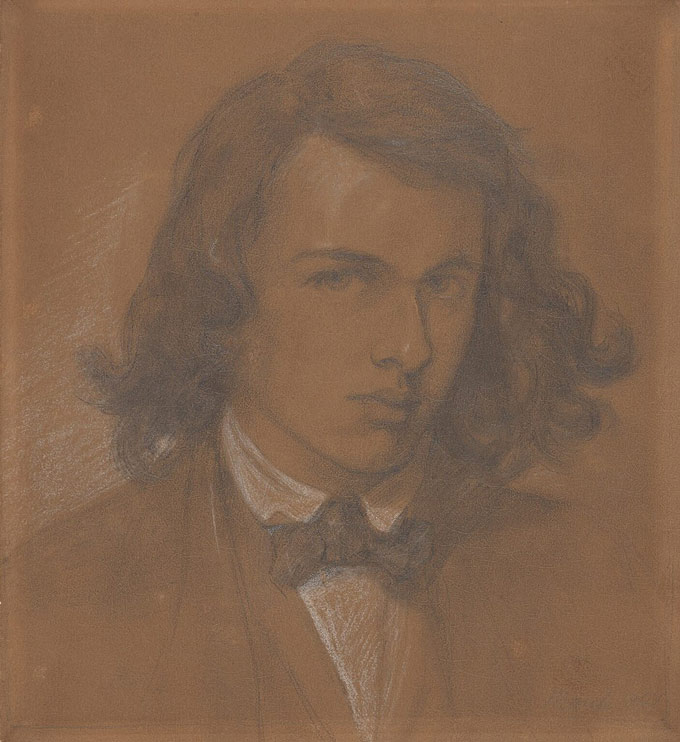

A self-portrait of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1847, aged 19

Rossetti suspected his future might – after all – lie in poetry. In a move revealing a brash self-confidence, he wrote to the famous poet and critic Leigh Hunt for advice. Hunt wrote back, saying it was easier to survive as a painter than a poet, so Rossetti decided to stay on the painterly path though he continued to write poetry. In March 1848, Rossetti contacted the artist Ford Maddox Brown, asking to become his pupil. Rossetti admired Brown’s style – preferring its vividness to the over-polished Academy paintings – but his letter gushed with so many compliments Brown assumed the young man was playing a joke on him. Grasping a club, Brown rushed to Rossetti’s home to teach the youthful jester a lesson. Reassured Rossetti’s praise was genuine, Brown took him on as a pupil that summer. But – though the two painters would remain close for years – their master-apprentice relationship was brief. Just like in the Academy, Rossetti was unable to submit his wayward nature to formal training’s demands.

The next painter Rossetti sought out was William Holman Hunt, after admiring his The Eve of St. Agnes. This picture was based a poem by John Keats, a big influence on Rossetti at that time, and Rossetti hoped Hunt might share his interests. Hunt did and he introduced Rossetti to another young like-minded artist, John Everett Millais. All three looked with distaste on the increasing materialism of Victorian society and disapproved of the pedantic Academy painters. They longed to revitalise art by returning to a style that was heartfelt and truthful, a style in which the painter would ‘observe everything and reject nothing’. They disliked what they saw as the mechanistic attitude of the Mannerist painters who’d come after Raphael and Michelangelo (hence the term Pre-Raphaelite) and wished to revive an art of intense detail and vivacious colour, taking inspiration from the clear lines of Florentine medieval frescos, the gem-like colours of early Flemish art and the complex compositions of the Italian Quattrocento painters. Naming themselves the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, they ardently set out their principles in a secret manifesto. This secrecy at first also applied to their movement’s name and they would simply initial their paintings ‘P.R.B’. Though just three young men started the Brotherhood, as time went on more artists would join or become associated with the group.

The Age of Innocence by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1785 or 1788). Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Pre-Raphaelites were reacting against this approach to painting.

Like many sensitive Victorians, the Pre-Raphaelites recoiled from the polluted, mechanical and highly commercial world the Industrial Revolution was shaping around them, often preferring to retreat into vivid dreams of medieval-inspired fantasy. Paradoxically, though, their art was also ultra-realistic, striving to depict people as they were and nature as it was. An early supporter, the wealthy and influential art critic John Ruskin, wrote, ‘Every Pre-Raphaelite landscape background is painted to the last touch, in the open air, from the thing itself. Every Pre-Raphaelite figure, however studied in expression, is a true portrait of some living person.’

These Pre-Raphaelite characteristics, under Rossetti’s brush, would become strongly associated with one particular subject – women. Vivid, detailed, strong, Rossetti’s depictions of women have been seen as combining the sexual and demure, the angel and the woman of the street, and the seeds of this approach can be seen in the early days of the Brotherhood. Rossetti contributed a poem to the first issue of the Brotherhood’s magazine, The Germ, which came out in late 1849. Perhaps prophetically, it depicts a painter being inspired by a vision of a woman who orders him to mix the human and divine in his art.

Rossetti was soon producing oil paintings in the early Pre-Raphaelite style. His Girlhood of the Virgin Mary had his sister Christina modelling the Virgin while his mother posed as Mary’s mum St Anne. In early 1850, Rossetti started his Ecce Ancilla Domini (or Behold the Handmaiden of the Lord). This picture, which also features Christina as the Virgin, shows an anxious Mary receiving the news she’ll bear God’s son. The Angel Gabriel – posed by Rossetti’s brother William – symbolically points the stem of a lily at the girl’s womb. Mary stares at the plant with compulsion and terror. She looks ill; she shrinks back from the angel; the interior of the house is claustrophobic, painted in a sickbed white, or a white representing the virginity soon to be lost. This painting could reflect the fear of sex Rossetti seems to have had at the time, a fear that wouldn’t have been unusual for a young Victorian. Though Rossetti was idealising women in his poetry, he seems to have had problems accepting the physical aspects of his relationships. But there’s also, if we look closely at the Virgin, an anticipation too. Christina’s red hair seems to be flickering; its strands appear charged with electricity. Red hair was somewhat disapproved of in Victorian England, with its vibrancy having connotations of moral looseness, but throughout his career, red female hair would fascinate Rossetti. The flickering hair might well portray the intriguing power of sensuality as much as the pallid Virgin symbolises anxieties around it.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Ecce Ancilla Domini, featuring his sister Christina as a red-haired Virgin Mary

The Pre-Raphaelites may have felt they were revolutionising art, but when they began to show their work, the critics were hostile. One, perhaps thinking of Rossetti’s Girlhood of the Virgin Mary, complained of ‘reproductions of saints squeezed out perfectly flat’. Charles Dickens – mocking the Brotherhood’s medievalism – proposed a Pre-Galileo Society for those who refused to believe the earth orbited the sun. In Spring 1850, the meaning of the initials P.R.B. leaked out, intensifying antipathy to the group. In 1848, attempted revolutions had rocked Europe so – to conservative minds – secret brotherhoods suggested cabals of plotting radicals. In a strongly Protestant England, the Brotherhood’s secrecy and medievalism also hinted at Catholic conspiracies. It seems Rossetti, to the annoyance of his Brotherhood, had been the one responsible for letting slip the name. Extremely sensitive to criticism, Rossetti soon tired of the ‘increasingly hysterical critical reaction that greeted Pre-Raphaelitism’ and decided – at the age of 22 – to stop exhibiting and just sell to private collectors. Despite the critics’ spiky words, there were always those eager to purchase his paintings. After showing the Girlhood of the Virgin Mary at the Free London Exhibition, Rossetti sold it for 80 guineas (around £12,000 today).

But the Pre-Raphaelites were about to meet a person who’d have a huge influence on them all. And especially on Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

The Pre-Raphaelites’ Discovery of Lizzie Siddal and an Encounter with Death in a Freezing Bathtub

Though the Pre-Raphaelites disparaged many of the ideas of the art establishment, one practice they didn’t abandon was using models. Sometimes they persuaded friends or family members to pose; occasionally, when they could afford it, they hired professionals. But often they’d rove London’s streets seeking out ‘stunners’, the Pre-Raphaelite term for the strikingly beautiful – but also somewhat unusual-looking – women they knew would give their paintings an extra pizzazz. Or they just looked out for likely models while going about everyday errands.

One winter day in 1849, legend maintains, Walter Deverell – an artist and friend of the Pre-Raphaelites – went with his mother to a hat shop close to Leicester Square. He spotted a young woman working in the shop’s backroom – an apprentice, apparently – and was immediately amazed by her long red hair and statuesque, slim figure. Walter begged his mother for an introduction and discovered the young lady was named Elizabeth – or Lizzie – Siddal. Deverell would burst into the studio in which Rossetti and Holman Hunt were painting and blurt out, ‘You fellows can’t tell what a stupendously beautiful creature I have found … She’s like a queen, magnificently tall!’

Recent research, however, indicates that Lizzie didn’t just passively wait for an excitable Pre-Raphaelite to stumble upon her. Lizzie Siddal – who’d loved sketching since she was a child – had her own artistic aspirations. She’d taken some of her drawings to show Walter’s mum, whose husband was the secretary of the London School of Design. Hearing about Lizzie, Walter rushed round to the hat shop and – upon seeing her – was determined she should sit for him

Elizabeth Eleanor Siddall (she’d later drop the last ‘l’ of her surname) was born in London on July 25th 1829. Her father ran a cutlery business and Lizzie was the third of eight children. One brother, Harry, appears to have had a mental impairment. Though little is known of her early life, it seems Lizzie liked to draw and read poetry. One of her favourite poets was Tennyson and it’s said she discovered his work when she spotted one of his poems on a sheet of paper that had been used to wrap butter. The family – though respectably lower-middle class – were poor. It’s not known if Lizzie attended school though she definitely learned to read and write, but when still quite young she had to go out to work to help support the family. She laboured long hours in the milliner’s shop under often tough conditions and her family fretted about her fragile health.

These circumstances – along with the fact artists’ models could earn far more than milliners’ apprentices – likely inclined Lizzie’s mother to contemplate allowing her to pose for Deverell. The Victorians, though, viewed such an occupation as disreputable, even a little like prostitution. Too frightened to approach Mrs Siddall himself, Walter sent his mother round in a grand coach. Awed by this carriage rocking up outside her modest home on the Old Kent Road, Mrs Siddall agreed to Walter’s request though the 20-year-old Lizzie continued part-time for a while at the hat shop. Walter introduced Lizzie to other artists and Rossetti said that when he met her, he felt his ‘destiny was defined’.

Deverell had Lizzie Siddal model as Viola in his Twelfth Night (1850) and she also appeared in paintings like Holman Hunt’s A Converted British Family Sheltering a Priest from the Persecution of the Druids (1850) and Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus (1850-1). She posed for Rossetti for the first time for Rossovestia (1850), one of his lesser-known paintings. The use of such a model – like much connected with Pre-Raphaelitism – was controversial. Though in the modern era Lizzie might have found work as a supermodel, her willowy limbs, gaunt face and coppery hair weren’t considered conventionally attractive in the early Victorian epoch. (One female journalist labelled red hair ‘social suicide’.) Through featuring in famous paintings, however, Lizzie helped change such perceptions.

Even the Pre-Raphaelites’ close circle didn’t quite know what to make of the delicate, reserved young woman with her tendency towards sadness and unusual brand of beauty. A female acquaintance recalled, ‘Elizabeth’s eyes were a kind of luminous golden brown agate colour, slender, elegant figure, tall for those days, beautiful deep red hair that fell in soft heavy wings … She did not talk happily, (was) excited and melancholy, though with much humour and tenderness.’ A male friend remembered Lizzie Siddal as ‘sweet, gentle and kindly, and sympathetic to art and poetry … Her pale face, abundant red hair and long thin limbs were strange and affecting, never beautiful in my eyes.’ Rossetti’s brother William felt she was ‘a most beautiful creature with an air between dignity and greatness; tall, finely formed with a lofty neck and regular though somewhat uncommon features; greenish-blue “unsparkling” eyes, brilliant complexion and a lavish heavy wealth of copper-golden hair … a modest self-respect and disdainful reserve; her talk had a sarcastic tone.’ Though impressed with her looks, William still considered Lizzie ‘not physically beautiful enough’ to represent Viola in Deverell’s Twelfth Night. It’s interesting that perceptions of Lizzie could differ markedly, with her eyes – for instance – described as both ‘agate brown’ and ‘greenish-blue’, as if people tended to project their own notions onto the quiet though striking woman.

One of the most famous pictures Lizzie posed for was John Everett Millais’ Ophelia (1852). The painting depicts a scene from Shakespeare’s Hamlet in which Ophelia – sent mad by her father’s death and her rejection by Prince Hamlet – commits suicide by allowing herself to fall into a river, which she then floats down. In the obsessive Pre-Raphaelite manner, Millais wanted his picture to be as true to life as possible and this obsessiveness would mean the threat of death was not limited to his canvas. After spending hours on the banks of the River Ewell near Kingston-upon-Thames painting water, flowers and plants, Millais decided it was time to place Lizzie in his picture. In his quest for realism, he had her pose in a bathtub – filled with water from the filthy Thames – wearing a silver-embroidered antique wedding dress. It was January and the studio was freezing. Millais put candles and lamps under the bath to keep the water warm, but they kept going out. Millais relit them yet – as he became more and more absorbed in the details of his painting – he forgot to check the flames.

John Everett Millais’ famous Ophelia, for which Lizzie Siddal posed in a freezing bath

Lizzie lay in the bitterly cold bath for five hours and never complained once or asked Millais to relight the lamps. Maybe she didn’t dare – her family were poor, one brother had just died of TB and she knew she was set to earn more in that afternoon than she would in a whole year as a milliner’s apprentice. Jerking from his artistic trance, Millais realised Lizzie was shivering and looking feverish. He helped her out of the tub, but it was clear she was desperately ill, probably with pneumonia. Her family called a doctor – an enormous and unusual expense for people in their financial straits – and Lizzie’s father threatened to sue Millais, who agreed to pay the medic’s bill. The doctor probably prescribed laudanum – a tincture of opium in alcohol. Lizzie – though she recovered from her ordeal in the bath – would become addicted to this substance, a dependency which may have begun in the aftermath of that freezing episode. Her decline into addiction would lead to worsening physical and mental health.

Sketch of Lizzie Siddal painting by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Lizzie Siddal, however, went on posing for the Pre-Raphaelites. She modelled frequently for, and became especially close to, one particular artist – Dante Gabriel Rossetti. She’d visit him – often secretly – in his new home and studio at Blackfriars in the City of London. (Located just north of Blackfriars’ Bridge, the studio’s site is now entombed below Blackfriars’ Station.) Lizzie and Rossetti became lovers. Though, after modelling for a couple of years, Lizzie had earned enough to quit the hat shop, Rossetti – perhaps jealous – would persuade Siddal to give up modelling for other artists and pose just for him. Charles Allston Collins, the younger brother of the author Wilkie, asked Lizzie to sit and remembered the ‘freezing’ refusal he received. Lizzie, at some point, moved in with Rossetti at Blackfriars – a scandalous arrangement in Victorian times. The extreme reserve of Lizzie’s character, however, appears to have extended to sexual matters, a factor that would soon cause issues in her relationship with Rossetti. Together in Blackfriars, the couple would experience intense creativity and intense strife, struggling with the demons of drugs, frustration, infidelity, failing health, depression and death.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Life with Lizzie Siddal – Drug Addiction, Affairs and the Looming Spectre of Death

Over the next decade or so, Rossetti had Lizzie model for numerous oil paintings and watercolours, as well as sketching her obsessively. Between 1850 and 1862, he made over 60 drawings of her, drawings that were often relaxed and personal. She featured in his medievalist fantasies depicting queenlike figures and the restraints of courtly love, such as King Arthur and the Weeping Queens and the 1860 painting Regina Cordium.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Regina Cordium (1860), featuring Lizzie Siddal

Rossetti frequently sketched her drawing and painting and Lizzie had certainly not given up her artistic ambitions. She made pen drawings and painted oils and watercolours as well as writing subtle melancholy poems. Life was challenging for aspiring female artists in the Victorian era. They couldn’t study at the Royal Academy schools despite the fact that when the Academy had been established in the previous century, two of its founders had been women. Female artists were usually dependent on males for financial assistance so an artistic life would probably be impossible without a supportive husband or well-off family. In this respect, Lizzie Siddal was, for a time, luckier than most. Rossetti encouraged her to draw and paint and tutored her. John Ruskin declared her a ‘genius’ and even gave her an allowance of £150 a year to enable her to paint, a sum that compared favourably to the £24 she would have earned in the hat shop. She was the only female painter included in the Pre-Raphaelite Exhibition of 1857. Though, as other Pre-Raphaelites had, she received mockery from critics, she sold a painting – Clerk Saunders (1857) – to an American collector.

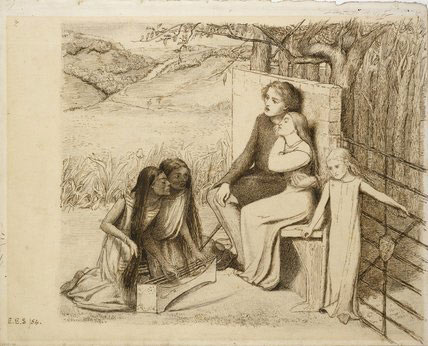

Lady Clare (1857) by Lizzie Siddal

But things were still difficult. Lizzie’s health was not improving. It’s not clear what malady Lizzie Siddal suffered from – suggestions have ranged from tuberculosis to anorexia to bulimia to a gastrointestinal ailment – but she was often weak and sick. Her laudanum addiction was becoming more severe, not helped by the fact the drug could be bought in any apothecary’s shop without a prescription. Strains were showing in her relationship with Rossetti. When, in 1855, Ford Madox Brown and his wife Emma visited the couple, the two women went out shopping, but when they got back Rossetti accused Emma of encouraging Lizzie to complain about him. The ravages of Lizzie’s illness were also becoming more apparent. Arriving at the Rossetti apartment one day, Brown – perhaps somewhat morbidly – noticed her ‘looking thinner and more deathlike and more beautiful and more ragged than ever, a real artist, a woman without parallel for many a long year.’

An ink drawing by Lizzie Siddal showing two lovers listening to music

As Lizzie grew sicker, Rossetti became more restless. Despite his gregarious personality, with Lizzie his social life was restricted. As well as the Browns, the Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones and his wife sometimes visited their apartment. The poet Algernon Swinburne also popped round and – knowing Lizzie’s enthusiasm for poetry and literature – would read to her. Rossetti, Lizzie and Swinburne sometimes went to the theatre. Swinburne noted Lizzie was ‘quick to see and so keen to enjoy that rare and delightful fusion of wit, humour, character painting and dramatic poetry in Elizabethan drama.’

In addition to Lizzie’s illness and addiction, Dante Gabriel Rossetti was finding it increasingly hard to deal with her sexual restraint. Rossetti had begun seeking other models and sometimes his relationships with these women went well beyond the professional. On returning from a trip to France, Lizzie found out about an affair – which was probably not Gabriel’s first – with Annie Miller, a frequent model for Holman Hunt and also Hunt’s lover. Annie posed for Rossetti as Helen of Troy. Lizzie was enraged, telling Ford Maddox Brown she wanted nothing more to do with the painter. She decamped for a while to Bath, in the forlorn hope its famous spa might help her illness.

Helen of Troy by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1863), featuring Annie Miller

One night in 1856 Rossetti was walking through Central London when he became aware of someone flicking peanuts at him. The peanut flicker turned out to be a prostitute called Fanny Cornforth. Struck by her voluptuous figure and thick wavy ginger hair, Rossetti immediately asked her to model and she agreed. Unlike the restrained and semi-respectable Lizzie, Fanny was an earthy girl, a blacksmith’s daughter from Sussex with a strong lower-class country accent. Though he couldn’t resist praising Fanny’s beauty, William Rossetti wrote she had ‘no charm of breeding, education or intellect’. Fanny soon began an intimate relationship with Gabriel, exhibiting none of Lizzie’s sexual reserve. Rossetti was profoundly affected by this carnal awakening, with his poems becoming more explicit and erotic, scattered with passionate metaphors and phallic symbols.

His portraits of Fanny are far more sensual than those of Lizzie. They’re fleshy and voluptuous with little hint of moral condemnation, all fiery hair and glowing skin, taking their influence right from the lustiness of the Venetian High Renaissance. One painting, 1859’s Bocca Baciata (or The Kissed Mouth) has Fanny pouting spectacularly, a rose in her hair and an apple of temptation positioned in front of her. The picture was inspired by a legend of a Saracen princess who – despite having sex 10,000 times with eight different lovers – still managed to present herself to her intended husband as a virgin bride. Rossetti had often combined his paintings with bits of poetry and on the back of Bocca Baciata he wrote: ‘The mouth that has been kissed loses not its freshness, Still it renews itself as does the moon.’

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Bocca Baciata, featuring Fanny Cornforth

Another well-known painting Fanny posed for was Found. This picture depicts a young farmer who, bringing a lamb to market in London, meets an old sweetheart by Blackfriars’ Bridge. His sweetheart has become an urban prostitute and the farmer unsuccessfully tries to ‘rescue’ her. Rossetti considered the painting – his sole attempt at tackling a contemporary subject – to be a failure. He couldn’t finish it and soon retreated back into his medieval dream world. But, in getting Fanny to pose as the prostitute, he certainly maintained the Pre-Raphaelite preference for vivid realism.

Found, by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, featuring Fanny Cornforth

It’s unclear how much Lizzie knew about Rossetti’s relationship with Fanny Cornforth, but one thing that did anger her was that Rossetti kept putting off the prospect of marriage. Though Lizzie had met Christina, she wasn’t introduced to Rossetti’s mother until 1855. His mother was against the match because of Lizzie’s lower social status, her poor health and lack of formal schooling. But, as her illness worsened, Lizzie eventually lost patience. She gave up Ruskin’s allowance and – via the spa town of Matlock – travelled to Sheffield (her father’s birthplace). There, determined to find success on her own terms, she enrolled in Sheffield School of Art. Rossetti made occasional journeys to see her, but his letters to friends from this period hint at liaisons with other women. Though not much is known about this phase of Lizzie’s life, she ended up in Hastings, a town popular with recuperating invalids.

By early 1860, Lizzie’s family had become very concerned about her health. They contacted John Ruskin, who alerted Rossetti. Ruskin wrote to Brown, ‘Lizzie is ready to die daily and more than once a day.’ Brimming with remorse, Rossetti finally promised to marry her. Their wedding took place in Hastings on May 23rd 1860 though Lizzie was so weak she had to be carried from the hotel to the church. The newly-weds enjoyed a lengthy honeymoon in Paris they could barely afford before returning with two street dogs they’d adopted. Lizzie’s health seemed to recover somewhat, she was happier and even became pregnant. Rossetti blissfully painted and drew her though ominously – while Lizzie seemed entranced at the prospect of motherhood – she was still hooked on laudanum. On 2nd May 1861, a stillborn daughter was delivered. Lizzie plummeted into depression. A friend recalled her rocking an empty cradle and saying, ‘Hush, you’ll waken it.’ She also suspected Rossetti was once again cheating on her. As for Rossetti, in later life he’d claim sounds in his house were the phantom footsteps of his stillborn daughter at the age she would have been then.

The Death of Lizzie Siddal and the Burial of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Poetry Book

In the early evening, on February 10th 1862, Gabriel and Lizzie went out to dinner with Swinburne. During the meal, Lizzie seemed sleepy, but maintained she was OK. The couple returned to their apartment and Rossetti went out again at about 8.00 pm, to teach an art class at the Working Men’s College. He left his wife preparing for bed and noticed she’d taken half-a-bottle of laudanum. Coming back a few hours later, Rossetti found her comatose. The vial of laudanum on the bedside table was now empty. There were claims – never substantiated – that Lizzie had fastened a note to her nightdress reading, ‘Please take care of Harry’ (her mentally handicapped brother).

Rossetti, it’s said, slipped the note into his pocket before calling a doctor and one of Lizzie’s sisters. After they arrived, Rossetti left again, to call on Ford Maddox Brown. Brown insisted the note be burnt. This was to ensure Lizzie wouldn’t be declared a suicide and, therefore, refused Christian burial. The two then returned to Rossetti’s apartment. During the night, Rossetti summoned three more doctors but it became increasingly obvious Lizzie had no hope. She passed away in the morning, just after 7.00 am. An Inquest the next day ruled she’d died from an accidental overdose. At the time of her death, Lizzie was pregnant again. It’s possible she feared the baby had stopped moving and was unwilling to face the trauma of losing another child.

William Rossetti’s daughter Helen Rossetti Angeli would claim, ‘Lizzie’s last message, as reported, is touching and romantic, but she did not write it.’ Helen may have been attempting to suppress a rumour that Gabriel had pushed Lizzie towards suicide or even murdered her. Oscar Wilde had spread a story that Rossetti had shoved the bottle of Laudanum into Lizzie’s hands and yelled ‘Drink the lot!’ before storming out.

The idea Lizzie wrote a note may, however, be based on a misunderstanding concerning her last poem. This poem was written in an unsteady hand and William Rossetti suspected it had been composed under influence of laudanum. Rossetti may have been talking about this poem when he told his friend Hall Caine about a message Lizzie had left. The poem’s entitled O Lord May I Come:

Life and night are falling from me,

Death and day are opening on me,

Wherever my footsteps come and go,

Life is a stony way of woe.

Lord have I long to go?

Hallow hearts are ever near me,

Soulless eyes have ceased to cheer me:

Lord, may I come to thee?

Life and youth and summer weather

To my heart no joy can gather.

Lord lift me from life’s stony way!

Loved eyes long close in death watch for me:

Holy death is waiting for me –

Lord, may I come to-day?

My outward life feels sad and still

Like lilies in a frozen rill;

I am gazing upwards to the sun,

Lord, Lord, remembering my lost one.

O Lord, remember me!

How is it in the unknown land?

Do the dead wander hand in hand?

God, give me trust in thee.

Do we clasp dead hands and quiver

With an endless joy forever?

Do tall white angels gaze and wend

Along the banks where lilies bend?

Lord, we know not how this may be:

Good Lord we put our faith in thee –

O God, remember me.

Devastated by grief, racked with remorse, Rossetti wouldn’t let Lizzie’s coffin leave their apartment for six days. He wrapped the manuscript of his poems – a pretty much complete book of verse, which he felt was the finest thing he’d ever produced – in her hair and let it rest next to her cheek. Lizzie ‘the beautiful wraith’ was buried in Highgate Cemetery, interred – despite their previous misgivings about her – in the Rossetti family plot. Some claimed Gabriel saw her ghost every night for the next two years.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Life after Lizzie Siddal – Drink, Drugs, Wombats and Naked Sliding down Banisters

Feeling his Blackfriars apartment contained too many agonising memories, Rossetti moved to a large Tudor house in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. The move didn’t, however, prevent him suffering from insomnia and nightmares, problems which would plague him for the rest of his life. Perhaps fearing loneliness, in Cheyne Walk he created a menagerie of bizarre and exotic animals. Rossetti owned a Pomeranian puppy named Punch, an Irish deerhound called Wolf, dormice, rabbits, peacocks, armadillos, a llama, a kangaroo, a zebu and parakeets. His animals often absconded, causing mayhem in his neighbours’ gardens and even attacking, killing and eating each other. Rossetti’s favourite pet was a Wombat named Top, a creature he brought to the dinner table and allowed to sleep on it during meals. Rossetti even dreamed of acquiring an elephant and training it to clean his windows, in the hope passing pedestrians would be intrigued, inquire about the house’s occupant and consider purchasing a painting.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s home at 16 Cheyne Walk. (Photo courtesy of Edward X)

Rossetti opened his house to eccentric humans too. Algernon Swinburne lodged with him and there were rumours of Swinburne and the painter Simeon Solomon sliding naked down banisters during riotous parties. Rossetti also reconnected with Fanny Cornforth and moved her into Cheyne Walk as his housekeeper, lover, model and muse. Tales abounded of all-night boozing sessions, nocturnal poetry readings and passionate arguments, with Rossetti said to have once flung a cup of tea in the face of George Meredith. (A novelist who achieved immortality by posing as the doomed poet Thomas Chatterton for the Pre-Raphaelite Henry Wallis.) On a darker note, Rossetti was prescribed the powerful sedative chloral hydrate to help him sleep. To rinse the chloral’s disagreeable taste from his mouth, Rossetti – who until then had been a teetotaller – started glugging down whiskey. He became addicted to both substances.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti painted in the drawing room of 16 Cheyne Walk by Henry Treffy (1882)

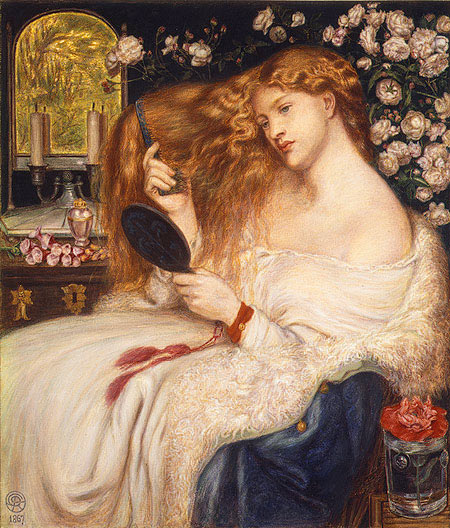

Despite – or maybe even because of – all this chaos, Rossetti continued to paint. In fact, his works were becoming increasingly popular and selling well, perhaps something to do with their subject matter. He developed his new sensual style, painting Fanny Cornforth obsessively, focusing on her majestic head of loose hair (which to many Victorians signified loose morals). She posed – disdainfully combing her locks – for his Lady Lilith, Lilith being a dangerous and seductive female demon in Jewish mythology. In a poem he wrote to accompany the picture, Rossetti praised ‘Adam’s first wife, Lilith’ the ‘witch he loved before the gift of Eve’ whose ‘enchanted hair was the first gold, And still she sits, young while the earth is old.’

Lady Lilith by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, featuring Fanny Cornforth (1867). In a more famous version of the painting, Rossetti substituted Fanny’s face for that of another model, Alexa Wilding.

In spite of his artistic triumphs, Rossetti suffered from doubts, fearing that – by churning out endless variations on the Pre-Raphaelite ‘stunner’ – he might be prostituting his art for commercial advantage. In a sombre moment, he reflected, ‘To be a painter is just the same as to be a whore.’ Perhaps such fears explain why Rossetti couldn’t finish Found – maybe he saw a little too much of himself in the picture. Some of Rossetti’s friends and supporters did suspect he was abandoning his Romantic ideals. Ruskin, for one, disapproved of his new paintings, declaring they were ‘as course as the prostitute who modelled for them’.

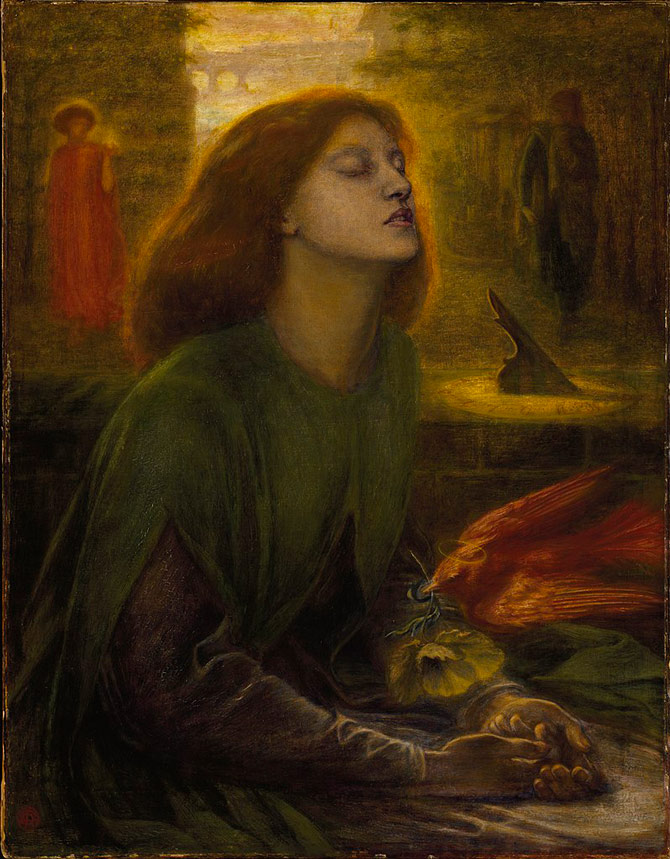

He also couldn’t escape memories of his wife. He made something of a return to his old preoccupations with medieval courtly love and queenly beauties admired from afar when in 1864 he began his Beata Beatrix. This picture depicts Beatrice – the great love of Dante Alighieri, who the poet adored despite only meeting twice – at the moment of her death. Beatrice – of course, modelled on Lizzie – is being mystically taken up to heaven. Her closed eyes hint at both deathly bliss and a drug-induced daze. A red dove, capped with a halo, drops a poppy – symbolising opium, sleep and death – into Lizzie’s hands. Rossetti always felt uneasy around the painting and bitterly reflected that artists often despise their best work. He knocked out numerous inferior versions of the picture for his clients, as if determined to besmirch its purity.

Beata Beatrix by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, featuring Lizzie Siddal

Fearing he’d betrayed the true spirit of his painting, Dante Gabriel Rossetti felt he had to seek artistic immortality via another means. He turned more of his attention towards his poetry and began to seriously consider putting a book of it out. This desire to grasp artistic renown was likely spurred on by the fact he knew his addictions to chloral and alcohol were worsening. There was also his belief that – despite his doctors’ reassurances – his sight was starting to fade. Rossetti, however, had a problem. Though he liked his recent verse, he felt much of the best stuff he’d ever penned was inaccessible. Much of his best work lay buried with Lizzie Siddal, deep in the earth of Highgate Cemetery.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the Exhumation of Lizzie Siddal, Vampire Legends and a Tsunami of Critical Hate

Rossetti was in a delicate position. Needing the manuscript, yet hating the thought of an exhumation, he worried about a disinterment becoming a subject of public gossip and about having to explain his intentions to his family, in whose plot Lizzie lay. Rossetti’s business agent, Charles Augustus Howell – perhaps motivated by the thought of how well a book from the famous artist might sell – seems to have soothed Rossetti’s doubts and persuaded him to go ahead with having Lizzie dug up. Rossetti signed power of attorney in the matter over to Howell, who knew the home secretary and so obtained an exhumation order without much fuss and without the other Rossettis finding out.

Gravestones marking the Rossetti family plot in Highgate Cemetery, where Lizzie Siddal is buried. (Photo courtesy of The Midnight Society)

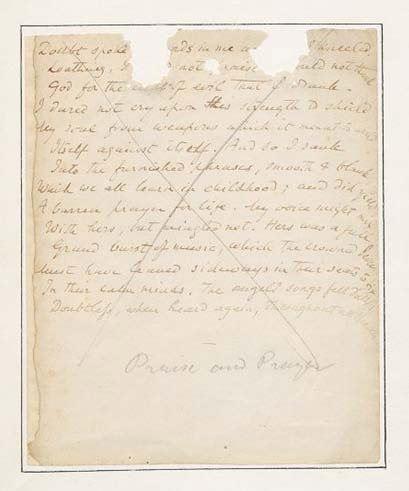

It seems much of the mythology about Lizzie being perfectly preserved also came from Howell. He likely invented this piece of macabrely Romantic folklore to ease Rossetti’s conscience. Howell may have also hoped that concocting an outlandish legend around Rossetti would boost the value of his work. None of the facts support Howell’s account of Lizzie’s pristine condition. After the manuscript was rescued from the grave, pieces of putrefaction had to be scraped off. Then – before Rossetti could start transcribing the poems – the book needed to be soaked in disinfectant for a fortnight. Rossetti found wormholes in the pages, which had obliterated some words. Despite having been thoroughly disinfected, the book gave off a revolting stench. Once he’d finished his grim undertaking, Rossetti destroyed the manuscript. Three pages, however, survived and are still held in libraries. The notion Lizzie’s hair had grown to a spectacular length is also likely to be little more than legend. The idea the hair of corpses can grow probably just results from the skin shrinking towards the skull, making the hair seem longer.

A page of the book of poetry Dante Gabriel Rossetti rescued from the grave of Lizzie Siddal. (Held in Houghton Library, Harvard University)

The claims about Lizzie’s ‘undead’ state may have, however, had quite a cultural impact. It’s thought the inspiration for the beautiful vampire Lucy Westerna in Bram Stoker’s Dracula might have come from accounts of Lizzie’s exhumation. Lucy, even more stunning in death than while alive, was laid to rest in ‘Kingstead Churchyard’, which many see as a fictional depiction of Highgate Cemetery. Stoker knew Rossetti – they were for a time neighbours – and he also knew and worked closely with Rossetti’s friend, the Manx writer Hall Caine. The exhumation of Lizzie Siddal seems a central event pulling together several strands of the Western vampire myth. Rossetti’s uncle wrote the first vampire novel while the disinterment of his wife possibly influenced Bram Stoker. And, in the 1970s, Highgate Cemetery would find itself the focus of a famous outbreak of vampire hysteria, with rumours a bloodsucking resident of the necropolis was prowling North London’s suburbs.

Despite having to deal with the gruesome manuscript and its scents of the grave, Rossetti felt his artistic resurrection might well be imminent. And, buoyed by getting his old verses back, he composed a new batch of poems, many of them – for the time – outrageously sensual. Much of the impetus for this came from a new mistress, Janey Morris. Rossetti and Burne-Jones had spotted Jane – the daughter of an Oxford stableman and laundress – in 1857 when they were painting murals at the Oxford Union Library. Amazed by her dark thick curly hair and queenly – almost haughty – features, they asked her to model. She sat for Rossetti as Guinevere and ended up marrying Rossetti’s friend William Morris in 1859. Morris – a poet, designer, socialist, free thinker, entrepreneur and crafts enthusiast – put his working-class wife through a programme of education. Due to her keen intelligence, Jane soon grew accomplished, learning several languages and becoming a skilled embroiderer. Her designs were sold through William’s interior decor firm, Morris and Co, in which Rossetti was a partner.

Rossetti’s affair with Janey seems to have begun in 1865. She’s said to have ‘consumed and obsessed him in paint, poetry and life’. He deluged her with verse and – as with his other muses – painted her constantly. While Lizzie had been the distant queen of courtly love and Fanny a symbol of sensuality, Janey was cast as a goddess. As Proserpine, she clutches a fateful pomegranate, resplendent in a loose flowing medieval gown. This goddess, however, deigned to accept Rossetti as her earthly lover. Rossetti wrote: ‘This hour be her sweet body all my song, now the same heartbeat blends her gaze with mine, One parted fire … her arms lie wide open, throbbing with their throng of confluent pulses, bare and fair and strong, and her deep freighted lips expect me now, amidst the clustering hair that shrines her brow, five kisses broad, her neck ten kisses long.’

Janey Morris poses as Proserpine, the Greek goddess of death and the underworld

Rossetti’s collection of verse – which mixed the poems salvaged from Lizzie’s casket with newer, more sensual efforts – was published in 1870. The poems, tragically, turned out to be too advanced for their epoch. Society was only just starting to become more open to the erotic. Rossetti’s verse perhaps also foreshadowed the development of a capitalist commodity culture, in which consumers are encouraged to eagerly – and greedily – look, touch, taste, feel, smell and experience. Though Rossetti may have heralded an emerging modern identity, his poetry was too much for most people in his own time. Rossetti had hoped his poems would make his name immortal, but the critics weren’t impressed.

The critic – and rival poet – Robert Buchanan was particularly disgusted. ‘There was no soul in this verse only body,’ he ranted, thundering against its ‘females who bite, scratch, scream, bubble, munch, sweat, writhe, wriggle, twist, foam and in a general way slather over their lovers.’ Frothing with outrage – and perhaps a little jealousy – Buchanan accused Rossetti and his circle of encouraging ‘a morbid deviation from healthy forms of life … all the gross and vulgar conceptions of life, which are formulated into certain products of art, literature and criticism, emanate from this bohemian class … There lies the seat of the cancer, there in the bohemian fringe of society, spreading daily like all cancerous diseases, foul in itself and creating foulness.’ Buchanan was suggesting Rossetti’s ‘impure’ art and poetry had their wellspring in the life Rosetti led as an adulterer and libertine.

Rossetti was distraught. As well as launching a frenzied assault on Rossetti’s good name, Buchanan had spelled out certain fears Rossetti held about himself. He’d long fretted that his more spiritual and idealistic aspects had become just a façade and that his erotic adventures had reduced him to little more than a seedy sensualist. Rossetti expressed this anguish in a poem called Lost Days, in which a man is confronted with past versions of himself. ‘I am thyself, what has thou done to me?’ each doppelganger demands before vowing to haunt the man forever.

So Rossetti felt his efforts to establish himself as a serious poet had failed. According to Hall Caine, he’d bitterly regret the grisly disinterment, castigating himself for yielding to the pull of literary ambition. The thought of Lizzie’s exhumation tormented Rossetti for the rest of his days. And the man who’d persuaded him to do it, Charles Augustus Howell, would soon acquire a reputation as a con artist and blackmailer. For Swinburne, Howell was ‘the vilest wretch I ever came across’ while Edward Burne-Jones characterised him as ‘a base, treacherous, unscrupulous and malignant fellow’. Howell attempted to gain control of John Ruskin’s finances, persuaded a lover to create fake Rossetti drawings and was even rumoured to be enmeshed in a plot to assassinate the French emperor Napoleon III. After Swinburne had entrusted Howell with some ‘burlesque and indecent letters’, they found their way to a publisher who used them to blackmail Swinburne into given up the copyright of a poem. Howell was discovered dead near a Chelsea pub on 21st April 1890 with his throat slit and a ten shilling coin in his mouth, the traditional death meted out to a slanderer. At Howell’s home, letters from many highly placed people were found carefully filed. On hearing Howell had died, Swinburne said he hoped he was in the eighth circle of Dante’s hell, where those who flatter then exploit others are covered in ‘a coating of eternal excrement’.

The Dark Goddess Foreshadows Death – the Decline of Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Devastated by the criticisms he’d received, Rossetti’s mental health declined. Increasingly paranoid, he suffered from hallucinations. But a piece of good fortune then came along from an unlikely source. As Janey and Rossetti had got closer, William Morris had developed a philosophy of free love, according to which husbands and wives shouldn’t stand in each other’s way of finding fulfilment. In early 1871, Morris even took out a joint lease with Rossetti on Kelmscott Manor, a fine Oxfordshire country house. That summer, Morris took off on a lengthy trip to Iceland, leaving the lovers behind to enjoy their affair. In bucolic surroundings and in the company of his beloved muse, Rossetti felt much better, his health improved and he again started to paint. The couple took long walks and lounged blissfully around Kelmscott’s garden, reading Shakespeare to each other. Rossetti would say it was the happiest summer of his life.

Kelmscott Manor, Oxfordshire, where Dante Gabriel Rossetti spent a blissful summer with his muse Jane Morris (Photo: Boerkevitz)

In Autumn 1871, Rossetti returned to London. Though his paintings were more popular than ever and were selling for ever more astronomical amounts, his problems again seemed to cloud in on him: his addictions, the traumas of his wife’s death and exhumation, and the critics’ savaging of his poetry. In June 1872, he suffered a mental breakdown. One night – as his wife had years before – he gulped down an overdose of laudanum, but unlike the luckless Lizzie Siddal, Rossetti survived. That September, he again joined Janey at Kelmscott and – though she tried to nurse him back to health – his days there were spent ‘in a haze of choral and whiskey’. By the next summer, he’d improved. He went back to Kelmscott, where Janey sat for him, but it was becoming clear their on-off relationship couldn’t continue. Janey was increasingly disturbed by his addictions, her two daughters had begun asking embarrassing questions about ‘Uncle Dante’, and Morris had restructured his firm, cutting Rossetti out. The polite charade that the two men were simply sharing the manor was becoming harder to maintain. In 1874, Janey had to banish Rossetti from Kelmscott. Rossetti would never return and he dropped into deep despondency.

Back at Cheyne Walk, Rossetti slid into an increasingly reclusive existence. Ill, addicted and depressed, he found it harder to work, but – when he did – the results could still be astounding. His paintings – which often featured Janey – took on a darker tone. In 1874, he produced the picture of her as Proserpine, the pomegranate she held symbolising death and entrapment in the underworld. An 1877 painting depicted her as the deity Astarte Syriaca. Rossetti’s take on this Near-Eastern love goddess – a more sinister counterpart of the Roman Venus – is full-lipped and prominently bossomed. Her solemn attendants, however, hold torches around which plants twine – plants that might be deadly nightshade. Though some clients were disturbed by Rossetti’s darker turn, he had no trouble selling his paintings. Astarte Syriaca went for £2,100 (over £250,000 in modern money).

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Astarte Syriaca, featuring Jane Morris

One source of support was Fanny Cornforth. She stayed on at Cheyne Walk until 1877, when Rossetti’s family – more involved now in his life due to his failing health – forced her to move out. Rossetti funded a house for her nearby and gave her several of his pictures. They exchanged humorous notes about their swelling waistlines. He called her ‘My Dear Elephant’ and sent her elephant sketches. Her name for him was ‘Rhino’ and he’d sign letters to her ‘Old Rhinoceros’.

By 1878, Rossetti could no longer paint. He spent his last four years overweight, sick, depressed, addicted and abandoned by many friends. He became housebound due to paralysis of the legs and suffered from Bright’s disease, a kidney ailment. On April 9th 1882 – while staying at a friend’s house in Birchington-on-Sea, Kent, in an attempt to improve his health – he died, aged 53. He’s buried in Birchington Churchyard.

No painter before Rossetti had worked so hard to merge the personal, psychological and sexual with archetypal myths. Rossetti tackled the huge themes of sex, life and death by drawing on his own struggles, traumas and loves. His work foreshadowed a whole stream of modern art in which painters would strive to do the same, with notable examples being the Symbolists and also Picasso, who was a fan of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Pre-Raphaelites.

But through all the chaos of Rossetti’s tragedies and triumphs, he was always haunted by the death of his first love and would never shake off the influence she had over him. Shortly before he passed away, Rossetti said of Lizzie Siddal: ‘As much as in a hundred years she’s dead, yet is today the day on which she died.’

(This article’s main image – showing Lizzie Siddal in John Everett Millais’ bathtub – is courtesy of The Kissed Mouth.)

Great stuff! Rossetti’s relationship with the tragic shop girl reminds me a bit of Shelley and his first wife. Despite his reputation as our greatest Romantic poet, Shelley didn’t lose much sleep over her suicide though.

Many thanks, Hugo, glad you enjoyed my take on the tragedies and adventures of Rossetti and Siddal. Several members of the Romantic movement seem to have had tragic – though fascinating – lives. I plan to write a blogpost on the life and death of Shelley at some point in the future.

Wonderful writing, thank you!

Many thanks, Erica.

Beautifully brought to life! Thank you!

Great overview David. And some nice illustrations. Look forward to the Shelly article.

Many thanks, Christopher, glad you enjoyed the post.

There is a wonderful portrait of Charles Augustus Howell by Frederick Sandys another artist on the periphery of the Brotherhood. Very enjoyable.

Thanks, Sidney, just checked it out – it is wonderful.

I absolutely loved this article. It was fascinating! As an English teacher, the writing was splendid. I look forward to reading more!

Thanks, Scott, glad you enjoyed the strange tale of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Lizzie Siddal.

Not sure how I stumbled across this but it was a fascinating read and really well written – thank you.

Brilliant piece, well written, I really enjoyed it!

I definitely had the broad strokes of this story from the Gay Daly book but the added details are so intriguing/sad/amazing, thank you!

I am reading Fred Vargas, “Un lieu incertain” at the moment. It begins like this : French and British policemen discover nine pairs of shoes with feet inside them all, on the pavement, in front of one of Highgate Cemetery entrance. Back to France, in the Eurostar, the inspector Danglard tells Lizzie Sindall’s story to his colleagues …

This is how I ended up reading your article. I loved it. I first saw Rosetti’s paintings at Tate Britain a while ago. I was and am still fascinated by the delicate, intense, clear and kind of fuzzy / dreamy feel of his work.

Thank you David for this great article.

Thanks, Aline, so glad you enjoyed!

I can’t believe there hasn’t been some epic movie made about this amazing story. Surely there’s some independent filmmaker out there looking for a story to whet his skills in a directorial debut at someplace like Cannes. This has all the makings.

I agree – it is an amazing, though tragic, story.

Very interesting article! You may enjoy the mini-series “Desperate Romantics” which depicts the live and loves of the Pre-Raphaelites.

Thanks, Jenna, glad you enjoyed the article!