England has – legend says – long been menaced by a range of dragons, wyverns and fiery flying serpents, terrifying creatures that through history have lurked in forests, have slithered forth from ponds, fluttered around blasting farmland, skulked between the woodcut covers of excitable pamphlets, and inhabited the wilder parts of old yellowed maps. Fond of feasting on livestock; keen on devouring peasants or snaffling up travellers when feeling like a snack; prone to kidnapping village maidens and kings’ daughters; these beasts were dreaded for centuries throughout the countryside.

But where there are dragons, there are also dragon slayers. Most of the time, these monsters met their nemeses: usually in the form of a sword- or lance-wielding hero. These gallant souls – ranging from farmhands to passing knights to notable landowners – are commemorated up and down the country: in legends and folksongs, in stained glass and on carvings on church bench ends.

But, we may wonder – if such bold individuals existed – might we not expect to find some of their tombs? This blog post will be a search through the churches of drowsy villages, a probe through ruined chapels, a poke around isolated manor houses on fog-shrouded peninsulas in a hunt for the worn memorials, the dragon-decorated grave-slabs, the scale-and-sword-inscribed tombs rumoured to conceal the remains of those still celebrated today for ridding their localities of pestilent reptiles.

In our quest, we might stumble across the swords said to have killed such monsters. We’ll also explore how the tombs of dragon dispatchers have influenced Britain’s best-known Romantic poets and absurdist authors. We’ll unearth accounts of giants’ bones being exhumed, in addition to learning of bottomless pools, dragons over a mile long, eccentric ceremonies involving bishops, the most enormous pies and puddings ever baked, and desperate attempts to outwit the Devil. We’ll also investigate the dark obsessions, sinister fears and strange archetypes that lurk behind tales of dragons and those who cull them. Come with me and we’ll see if we can find England’s three best dragon slayers’ tombs.

Number One: The Knucker and the Slayer’s Slab, Lyminster, Sussex – Bottomless Pools, Greedy Dragons and Massive Pies

A horrendous water dragon – known as a knucker – was reputed to live in a deep pond, called a knucker hole, near Lyminster, Sussex. This knucker – which had the appearance of a winged and hideous sea serpent – would slink out of its pool to rampage around the countryside. It destroyed whole fields of crops right before harvest, gobbled up livestock and even ate humans, though – according to some accounts – it only wolfed down beautiful maidens.

One version of the story states that the King of Sussex – this all occurred in Saxon times, around the 5th century – grew so vexed with the dragon he offered the hand of his daughter in marriage to any man who could kill the monster. A young wandering knight, hearing of this hazardous deal, took up the challenge. After a bloody and exhausting battle, he managed to slay the beast. Following his wedding with the princess, the knight settled down in Sussex. He lived a long and happy life and – after he passed away – the locals gave him a special tombstone to honour his achievement.

A medieval knight slays a dragon.

That gravestone can still be seen in Lyminster, in St Mary Magdalene’s Church. The stone – known as the Slayer’s Slab – is very worn: it originally lay in the churchyard but was moved inside to prevent further damage. If you examine it, locals say, you can make out a sword sculpted against a background of dragons’ ribs. A different piece of folklore claims these ridges were instead caused by a vengeful dragon trying to claw its way down to the slayer in the grave.

Variations on the knucker legend have – rather than knights – men of humbler origin taking the dragon on. Some claim a Lyminster farm boy called Jim Pulk challenged the beast; others say it was a young man named Jim Puttock from the village of Wick or the nearby town of Arundel.

Jim Pulk is said to have baked the most enormous pie and laced it with poison. He loaded this gargantuan pastry onto a cart, which needed two horses to pull it, and took it to the knucker hole. The knucker devoured the pie – and the horses and the cart, but the poison soon worked its effects and the monster died. Jim chopped off the dragon’s head with his scythe and took it as a trophy to the Six Bells Inn, where he intended to enjoy a pint to celebrate.

Seated in the pub, lauded by all as a hero, Jim took a hearty swig of ale and wiped his hand across his mouth to clear away some froth. Tragically, he still had some of the dragon’s noxious blood on his skin or – according to some legends – some poison from the pie. Jim swallowed a few drops, which was enough to kill him. Jim was buried in the churchyard under the Slayer’s Slab, which the local people had carved out of gratitude.

The Slayer’s Slab – can you make out the sword and the dragon’s ribs? (Photo: Odd Days Out)

The Jim Puttock take on the legend has the Mayor of Arundel offering a reward to anyone who could slay the knucker. A record of this tale – told in dialect – was taken down from an old hedger by one Charles G. Joiner in 1929 and published in Sussex County Magazine. According to the hedger, no one at first accepted the mayor’s challenge. The mayor was, however, desperate to get rid of the beast. This was perhaps understandable as the dragon would go ‘spannelling about the brooks by night to see what he could pick up for supper, like a few horses, or cows maybe, he’d snap ’em up as soon as look at ’em.’ Another unpleasant habit the monster had was sitting at a high point on a causeway and if ‘anybody come along there, he’d lick ’em up, like a toad licking flies off a stone.’

The mayor, therefore, doubled his offer and Jim Puttock stepped forward. The mayor commanded everyone to give Jim whatever he asked for, no matter the expense. Jim ordered a ‘gert iron pot’ from the blacksmith, masses of flour from the baker, vast quantities of apples from orchards, and enough lumber from woodsmen to make a ‘gert stack-fire in the middle o’ the square’. He then cooked ‘the biggest pudden that was ever seen’. Jim transported the pudding on a cart to where the knucker was lying, with his immense body sprawled across a hill while ‘tearing up the trees in Batworth Park with his tail.’ His curiosity aroused, the knucker spoke to Jim:

‘How do, man?’

‘How do dragon?’ said Jim.

‘What you got there?’ said dragon, sniffing.

‘Pudden,’ said Jim.

‘Pudden?’ said knucker. ‘What be that?’

‘Just you try,’ said Jim.

In a few seconds, the dragon snaffled up the pudding, the horses and the cart. Jim himself almost got eaten, but avoided being sucked into the dragon’s mouth by hanging onto a tree.

‘Twern’t bad,’ said the knucker, licking his chops.

It soon, however, became clear that the gigantic pudding was more than even the greedy knucker could cope with. The knucker was soon rolling around, roaring, bellowing, vomiting, swivelling his massive eyes and lashing his tail. Jim, meanwhile, had somewhat casually nipped to the pub for a beer. When he came back, the knucker was complaining of a terrible bellyache.

‘Never mind,’ said Jim. ‘I’ve got a pill here, soon cure that.’

‘Where?’ said the knucker, bending his great head forward.

‘Here,’ said Jim.

Jim brought out an axe from behind his back and cut the dragon’s head clean off. Unlike the other Jim, though, Jim Puttock didn’t die after decapitating the monster. He lived out his years and – when his time came – he was buried under the Slayer’s Slab.

The famous Lyminster knucker hole – from where a horrid dragon slithered forth. (Photo: dellagriffiths)

Knucker holes are a common feature of Sussex. These curious pools might only be 20 feet or so across, but are exceptionally deep. They’re often reputed to be bottomless. A story says that, after the knucker’s time, the men of Lyminster tied six bell ropes from the church together and fed them down into the pool, but they didn’t touch the bottom. The pool was eventually explored by divers, who discovered it had a depth of around 30 feet. Knucker holes are fed by underground springs, keeping the water fresh and relatively warm. Though you’d imagine Lyminster’s knucker hole would have been polluted by the poisonous dragon, the pond’s water was actually thought to have healing properties. Locals used to bottle it as a cure for all ailments. Today, sadly, the famous knucker hole is fenced off with barbed wire and used to breed trout.

A knucker hole at Lancing was believed to be bottomless or to go down to the other side of the world. More knucker holes could be found at Shoreham, Binstead, Worthing and in other places and many were reputed to have their dragons. People noticed the warm pools gave off steam in frosty weather – perhaps the legends of dragons partly came from that. Maybe the supposedly fathomless ponds connected the knucker holes in the popular mind with another bottomless pit – that occupied by the great dragon, the Devil. Or parents might have used stories of knuckers to scare their children away from the dangerous pools.

A knucker hole on the Sompting Estate, Sussex, England – apparently, a cart was once lost in its depths. (Photo: Sompting Estate)

It’s interesting that the tale of the Lyminster knucker is set in Saxon times. ‘Knucker’ probably comes from the Saxon word ‘nicor’, meaning ‘water monster’. This term can be found in the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf, in which the epic’s hero clambers ‘o’er stone-cliffs steep … narrow passes and unknown ways, headlands sheer, and the haunts of the nicors.’

Similar words exist across European cultures. The word ‘nixie’ can mean water spirit. In Iceland, nykur means water horse; in German, a nickel is an underground goblin while a similar creature is known as a knocker in Cornwall. Water spirits are called neck in Scandinavia and näkki in Finland. Näcken are Scandinavian water men while näkineiu are mermaids in Estonia. Most of these words describe some kind of frightening or supernatural being, often connected – like knuckers – with water. Maybe a similar connotation can even be found in the colloquial term for the Devil ‘Old Nick’.

As for the Slayer’s Slab, the gravestone bears no inscription so it’s impossible to know who it commemorates. A close examination, however, will show that – rather than a sword lying on a dragon’s ribs – the stone actually depicts a cross on a herringbone background. This unusual stone may have been co-opted to add colour to a local knucker legend or might have actually generated the legend itself, with the story being invented to explain the stone. I’d suspect the former explanation is more probable. One child in the 1930s, however, believed the tales about the dragon so implicitly he’d regularly leave snapdragons on the grave. A stained glass window in St Mary Magdalene’s Church shows Jim Pulk offering the dragon his pie, but it’s hardly the size of the pie of legend or likely to finish the beast off.

Window showing dragon slayer Jim Pulk, with the knucker, Lyminster. The pie is rather smaller than in the legend. (Photo: Odd Days Out)

Number Two: Tomb of Piers Shonks, the Dragon Slayer of Brent Pelham, Hertfordshire

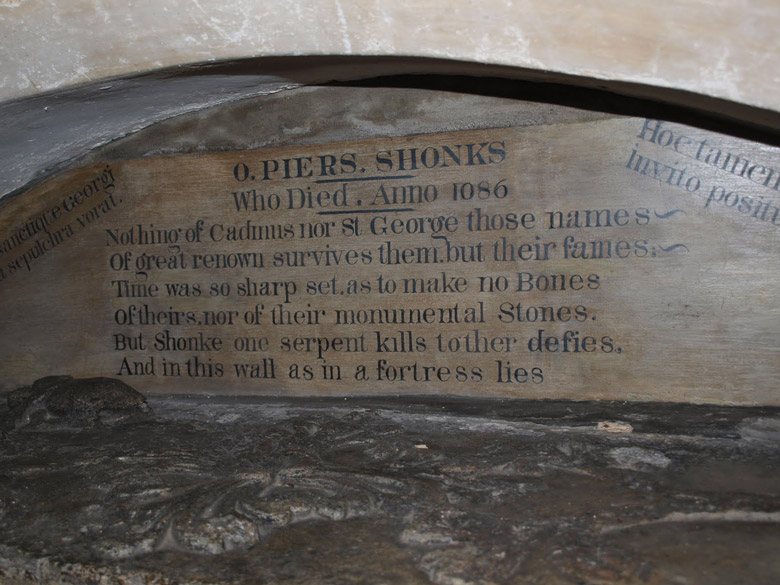

If you were to browse around St Mary’s Church, in the village of Brent Pelham, Hertfordshire, you might come across the strangest tomb in an alcove in the nave’s north wall. There’s an ornately carved slab of black marble – it’s well-worn, but if you examined it, you’d make out a dragon and flames as well as angels and an elaborate cross. The dragon – via a spear thrust in its mouth – is receiving its comeuppance. Above the slab is an inscription leaving no doubt this tomb commemorates a dragon slayer:

‘Nothing of Cadmus nor St George, those names

of great renown, survives them but their fames;

Time was so sharp set as to make no Bones

Of theirs, nor of their monumental Stones.

But Shonks, one serpent kills, t’other defies,

And in this wall, as in a fortress lies.

Piers Shonks was a local lord who slew the infamous dragon of Brent Pelham, a winged serpent with armour-like scales. This monster had made its home in a cave beneath the roots of an ancient yew tree that stood just outside the village, a den that proved a perfect base from which to terrorise the neighbourhood. Some time around the Norman Conquest, Piers Shonks – who resided in a moated manor house whose ruins can still be seen in Brent Pelham – promised to rid his domains of this reptilian menace.

Shonks, however, seems to have been more than just a noble – he had something of the magical and monstrous about him. A giant who – according to some accounts – stood at 23 feet tall, Shonks was famed as a hunter: rumour claimed his hounds were winged. Piers set out to face Brent Pelham’s terrifying dragon accompanied by just one servant and these faithful and swift dogs.

The inscription on the tomb of the dragon slayer Piers Shonks, in Brent Pelham, Hertfordshire, England. (Photo: Stepneyrobarts)

He confronted the beast at its lair and – after a long and bloody combat – killed it by shoving his spear down its throat. But Shonks wasn’t able to enjoy his triumph for long. There was an almighty crash of thunder, an overpowering stench of brimstone and the Devil himself appeared. The Fiend was furious about the slaughter of one of his favourite monsters and he promised that – when Shonks died – he’d claim his soul. Just to make sure the dragon slayer understood his spirit was doomed, the Devil pledged that Piers wouldn’t escape his scaly clutches whether he was buried in the church or outside it.

Piers didn’t seem worried about the Devil’s threat. He lived a fulfilled life and – when he lay dying in 1086 – he asked a servant to bring him his bow. With the last of his strength, Piers fired an arrow and demanded he be buried wherever the arrow came down. The arrow flew through a window of the church and collided with its north wall so that was where his tomb was built. As Shonks was interred neither in the church nor outside it, the Devil was thwarted from stealing his soul.

But, as I said, Piers Shonks had something uncanny about him. Even the obstacle of death didn’t prevent him protecting the people of Brent Pelham. A man – named Jack O’Pelham – once stole a faggot, but just before he reached his home, the spirit of Piers Shonks appeared. Jack fainted from shock and was so shaken he vowed he’d never again commit a criminal act. Shonks also haunts the churchyard and church, frightening any who’d cause mischief in these holy precincts.

The dragon on Piers Shonks’s tomb, Brent Pelham – does this depict the manner in which Shonks disposed of the beast? (Photo: Icknield Indagations)

To any sceptics who might doubt the legend of Piers Shonks, villagers have a few things to say. Folklore states Shonks was a giant and its said that – in 1835 – Shonks’s tomb was opened. The bones found within might not have quite been those of a 23-foot man, but the skeleton was of a person who’d have measured nine feet. Some think that, before the dragon took up residence near Brent Pelham, it lived close to the village of Barkway. Out of gratitude for the slaying of the monster – until 1900 – Barkway paid Brent Pelham six shillings a year ‘dragon rent’. There’s also Brent Pelham’s name. ‘Brent’ means ‘burnt’, which refers to the destruction the dragon wreaked.

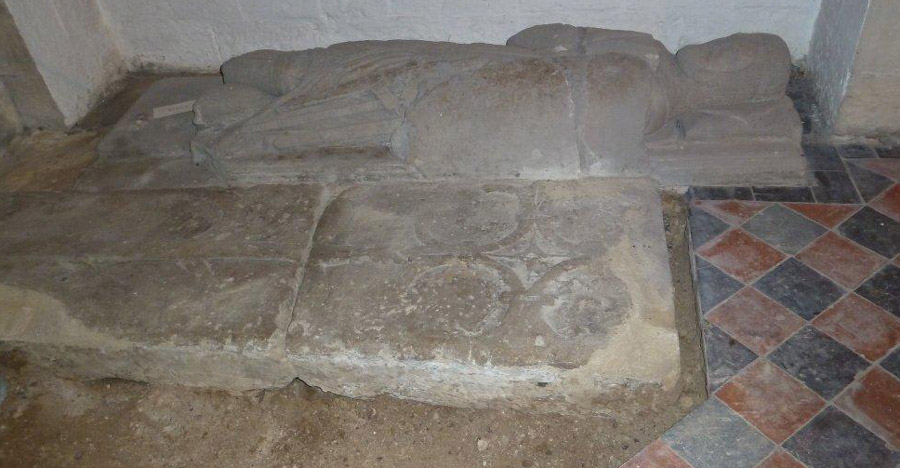

The sceptics might, however, have a few things to say back. A stylistic analysis of the marble tomb suggests that – if Piers Shonks died in 1086 – the tomb would have been constructed about 200 years too late. The tomb – like the Slayer’s Slab – has no inscription to indicate who lays within it, but its carved motifs don’t prove it holds a dragon slayer’s bones. The fiery dragon likely represents the Devil. The tomb is also decorated with the emblems of the Four Evangelists: an angel, eagle, lion and bull. These, along with the cross, are likely to symbolise Christianity overcoming Satan’s power. A devilish dragon being skewered in the mouth is also a common medieval image.

The inscription on the wall above the tomb is a much later addition, probably dating from the late 16th or early 17th century. Perhaps an antiquarian of that time – knowing Piers Shonks’s legend and seeing a dragon on the slab – erroneously connected the two. Some suspect a vicar of Brent Pelham, the Reverend Raphael Keen (died 1614), had the lines chiselled there.

The tomb of dragon slayer Piers Shonks, Brent Pelham. Note the Christian symbols of an angel and cross as well as the Four Evangelists’ emblems. The angel is carrying a man up to heaven in a piece of fabric, but he looks a little small for the gigantic Shonks! (Photo: Icknield Indagations)

As for ‘Brent’ meaning ‘burnt’, this is far more likely to refer to a 12th-century fire that destroyed the village rather than flames a dragon vomited. Interestingly, though, ‘Pelham’ means ‘place of springs’, perhaps suggesting a link between dragons and water like in the case of the knucker above. The date the dragon slaying reputedly took place is also intriguing. Piers Shonks is said to have been a Norman knight and a number of dragon-slaying legends are set in the years around the 1066 Conquest. Norman-descended families could have propagated these myths to bolster their claims to their new lands.

Several common folkloric motifs can be seen in the Piers Shonks story. There’s the idea of a churchyard guardian. Some folktales claim the soul of the first – or last – person interred in a graveyard is tasked with guarding it. As a result, black dogs were sometimes buried in churchyards or church foundations – so their spirits could relieve human ghosts from such burdensome duties. At Brent Pelham, it seems, these responsibilities were assumed by the protective spirit of Piers Shonks.

As for the burial in the church wall as a ruse to evade Satan, similar tales can be found elsewhere. In Yspytty Ystwyth, Dyfed, a wizard who’d promised the Devil his soul ‘whether buried within a church or out’ tricked the Evil One by pulling off the same stunt. The Brent Pelham tale may have partly grown up to explain the tomb’s presence in the wall. The church was rebuilt in the middle of the 14th century so it seems the tomb is older than the church – might the tomb have originally not been in the wall but been incorporated into it during this reconstruction?

Number Three: The Sockburn Worm and the Tomb of Sir John Conyers, County Durham – Alice in Wonderland, Romantic Poets and a Dragon Slaying Sword

Effigy said to be of Sir John Conyers, slayer of the Sockburn Worm. (Photo: Brian Combs)

On the bridge across the River Tees between the villages of Croft (North Yorkshire) and Hurworth (County Durham) the oddest ceremony takes place. Whenever a new Bishop of Durham is selected, he must pause upon this bridge on his journey north, where he’s confronted by the sword-brandishing mayor of the nearby town of Darlington. The mayor tells him:

‘My Lord Bishop. I hereby present you with the falchion wherewith the champion Conyers slew the worm, dragon or fiery flying serpent which destroyed man, woman and child; in memory of which the king then reigning gave him the manor of Sockburn, to hold by this tenure, that upon the first entrance of every bishop into the county the falchion should be presented.’

This custom is a revival of a tradition that used to involve the Lord of the Sockburn (an eerie and isolated peninsula in a bend of the Tees) and every newly appointed Prince Bishop (who were once the powerful ecclesiastical and secular rulers of County Durham). The lord would make the speech above and present the falchion (a type of medieval sword) to the Prince Bishop who’d then give it back and bid the lord enjoy the possession of his lands. The ceremony was obviously a way in which the lord could show loyalty to the Prince Bishop while still having considerable freedom over his estate.

The Bishop of Durham receiving a replica of the falchion that killed the Sockburn Worm. (Photo: The Durham Cow)

The ceremony – for several centuries – seems to have been a big occasion. Bishop Cosin wrote about going through it in 1661 when fording the Tees. He stated that ‘the numbers of gentry, clergy and other people was very great, and at my entrance through the river Tees there was scarce any water to be seen for the multitude of horse and men that filled it, when the sword that killed the dragon was delivered to me with all the formality of trumpets and gunshots and acclamations that might be made.’

Legend does indeed claim that Sir John Conyers, a young local noble, slayed a dragon. The Sockburn Worm – either a wyvern (two-legged dragon) or flying serpent – had terrorised the peninsula for seven years, devouring farm animals as well as any humans who got in its way. The creature had exceptionally bad breath. A manuscript in the British Museum, dated from the first half of the 1600s, complains of its ‘monstrous venoms and poysons …. for the scent of the poyson was so strong, that no person was able to abide it.’

Shortly before the Norman Conquest, some say in 1063, Sir John decided something had to be done. He went in armour to Sockburn’s All Saints’ Church and pledged the life of his only ‘sonne to the holy ghost’. Hoping God was now on his side, he went out to face the horrid worm, armed with his falchion. Sir John hacked bravely at the beast while dodging its corrosive breath and – after an intense struggle – was triumphant. He kicked some of the worm’s stinking carcass into the River Tees before burying the rest on the peninsula. A grey stone – which you can still see today – marks where the dragon lies. News of Conyers’ victory spread through the nation and the king was so relieved to have his realm freed from the beast he granted Sir John and his descendants possession of Sockburn in perpetuity.

But though we can see the worm’s grave, what of Sir John’s tomb? All Saints’ Church is now a ruin, but for many years it contained a fine stone effigy of a recumbent knight, an effigy local people have always claimed decorated the resting place of Sir John Conyers. The knight is clad in a coat of mail; he holds a triangular shield and clutches a sword in his right hand. There’s a carving of a dog and wyvern fighting at his feet, which – it’s asserted – is a reference to the very wyvern Conyers killed. As the church fell into ever-greater disrepair, the effigy was moved into the somewhat more robust Conyers Chapel, which was added onto the church in the 14th century and reroofed in 1900. Sir John’s effigy remains there today.

A wyvern and dog fight at the foot of Sir John Conyers’ effigy, in Sockburn, County Durham, England. (Photo: Hypnogoria)

Though Sir John’s falchion was presented in the ceremony for hundreds of years, the sword used in the modern ritual is a replica. You can, however, still see the original, dragon-slaying sword. The sword was kept in Sockburn Hall manor house until 1947, when it was donated to Durham Cathedral. It’s displayed in a glass case and – for a small fee – you can see it as part of the Cathedral’s Open Treasure Exhibition.

The Conyers Falchion in Durham Cathedral – did this sword slay the Sockburn Worm?

The Sockburn Peninsula occupies a deep bend in the Tees. It’s sparsely populated and not on the way to anywhere else, giving it a spooky, isolated feel. There’s just an expanse of flat fields, the calm river, eerie silence; the only human structures are the manor house, the ruined church, and a few farm buildings. It’s as if the dragon’s ghost looms over the vicinity, injecting the venom of gloom into the air or hovering on the mist that rolls off the river. Despite its dreary quiet, however, Sockburn has managed to make some impressive contributions to literature and history.

The peninsula was a site of early Christian importance. Bishops were crowned there – with Higbald, Bishop of Lindisfarne, undergoing this honour around 780 AD and Eanwald, Bishop of York, in 796. A much later churchman associated with the area was the father of Lewis Carroll, creator of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. From 1843 to 1868, Carroll’s father was the rector of Croft, whose attractive church, rectory and churchyard jut out into the Tees next to the bridge where the falchion ceremony is performed. Carroll spent most of his adolescence in the village, having come there aged 11. Carroll’s fictional monster, the Jabberwock, might owe much to the legends of the Sockburn Worm:

‘Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the jubjub bird and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!’

He took his vorpal sword in hand:

Long time the manxome foe he sought –

So he rested by the Tum Tum tree,

And stood a while in thought.

And as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

And burbled as it came!

One, two! One, two! And through and through

The vorpal blade went snicker-snack!

He left it dead, and with its head

He went galumphing back.

‘And hast thou slain the Jabberwock?

Come to my arms, my beamish boy!

O’ frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!’

He chortled in his joy.

Was Jabberwocky inspired by the dragon-slaying legends around the Sockburn Worm? Illustration by John Tenniel 1871.

Might the Jabberwock be the Sockburn Worm and the vorpal blade Sir John Conyers’ falchion? One of 11 siblings, Carroll seems to have started making up stories to amuse his large family and the first verse of Jabberwocky was written at Croft. Carroll’s time there may have inspired other literary motifs. In Croft church is a sedilia – a kind of seat for the clergy, built into a wall – upon which is carved the face of a lion or cat. Looked at from a certain angle, when sitting in the pews, this creature appears to have an incredibly wide smile. If you stand up, however, the grin disappears, a kind of reverse of what happens to Carroll’s Cheshire Cat: ‘Well, I’ve often seen a cat without a grin,’ thought Alice, ‘but a grin without a cat. It’s the most curious thing I’ve ever seen in my life!’

In 1950, Croft Rectory’s floorboards were levered up, revealing a number of Victorian artefacts, including a child’s shoe – and a white glove, a glove of the kind the white rabbit might have worn in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Carroll may have taken even more inspiration from the north east of England. His sisters lived in Whitburn, now in Tyne and Wear, where he often visited them and where he wrote parts of Jabberwocky. He’s said to have met a carpenter while walking on a local beach and to have seen a stuffed walrus in the town. He also visited a house named Whitburn Hall – and played crochet on the lawn. The hall’s owner had recently introduced white rabbits into the grounds.

The grinning ‘Cheshire Cat’ in Croft Church that may have inspired Lewis Carroll

Some other literary figures linked with Sockburn were the Romantic poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth. In 1799, one Tom Hutchinson built a farmhouse at Sockburn, in which he lived with his sisters, Mary and Sara. Tom’s most famous achievement seems to have been breeding a 17-and-a-half-stone sheep, but his siblings would affect literary history. Wordsworth was distantly related to the family and he visited, bringing Coleridge. Wordsworth soon fell for Mary and the pair married in 1802. Coleridge – though married already – succumbed to Sara’s charms. She inspired a poem, Love, in which Coleridge depicts his sweetheart leaning against a statue that sounds similar to Sir John Conyers’ effigy:

She leant against the arméd man,

The statue of the arméd knight

She stood and listened to my lay

Amid the lingering light.

All this takes place in the moonlight ‘beside the ruined tower’ of a ‘ruin wild and hoary’ that could well be the remains of All Saints’ Church.

Despite all the inspiration it’s given, there’s plenty to query about the Sockburn Worm legend. Various explanations have been suggested for the tale. It may have evolved from memories of dragon-prowed Viking ships that raided up the River Tees or it may have simply been inspired by the wyvern on Sir John’s tomb. The Conyers family appear to have been of Norman descent and the story is set just prior to the 1066 Conquest. The tale then might – like some other English dragon legends – have been created to justify these newcomers’ landholdings in the area.

And what about Sir John Conyers’ falchion? We’re told Sir John slew the Sockburn Worm in 1063. The sword on display in Durham Cathedral features the heraldic decorations of a black eagle on one side of its pommel and the three lions of England on the other. This indicates the sword couldn’t have been made earlier than 1194, when the three-lion motif first appeared on the royal crest. Other details of the sword would probably date it to about 1260-70, around 200 years after Sir John supposedly slew his dragon. It’s possible that the weapon in Durham Cathedral was made to replace an earlier sword, but this must remain speculation. The legend is true in its claim that the Conyers were granted the manor of Sockburn, but this seems to have happened around the start of the 12th century, before the forging of the sword but after the reputed dragon slaying. The sword’s crossguard is, interestingly, decorated with dragons. All this would suggest sword and myth may have been created around the same time to boost the claims of the Norman interlopers, the Conyers, to their estates. The Conyers Falchion is still, however, a precious artefact, as only about half-a-dozen medieval falchions are thought to have survived.

The ruins of Sockburn Church, in which Sir John Conyers prepared to slay the dragon. Behind the ruins is the Conyers Chapel, in which the ‘dragon slayer’s’ effigy lies. (Photo: Ataffo)

As for the effigy of ‘Sir John’ which Coleridge so romanticised, it cannot be of the legendary dragon slayer. It dates to the middle of the 13th century. A memorial brass near the effigy in the Conyers Chapel does commemorate a Sir John Conyers, but – the plaque’s gothic lettering tells us – he died in 1394.

The idea the Conyers would hold their estates in perpetuity thanks to Sir John’s heroics has also proved false. The Conyers were at Sockburn for centuries, but in the late 1500s or 1600s they moved their family seat a little further north to Horden, near Peterlee, and sold Sockburn to the Blacketts, a family of Newcastle industrialists. This perhaps reflected the slow shift of wealth and power from feudal lords to merchants and manufacturers as the capitalist system took shape, but Sockburn’s new masters still treasured the falchion and still faithfully presented it to each new Bishop of Durham. The Blacketts seem to have sold off or rented out bits of Sockburn to various people as the years passed. As for the Conyers, some went to America, but the English branch of this once proud dragon-slaying clan fell into decline. In 1809, the 9th Baronet, Sir Thomas Conyers, was found living in a workhouse in Chester-le-Street and the family died out completely in 1910.

Sockburn Hall, viewed across the tombs of Sockburn’s abandoned All Saints’ Church. The current hall was built in 1834 on the site of an earlier structure.

The ceremony with the falchion on the bridge also dropped into sad decay. The last time the sword was publicly presented was in 1826, when Sir Edward Blackett handed the weapon to Bishop Van Mildert. There was a rather desultory ritual in June 1860 when the sword was presented to Bishop Villiers when he was crossing the Tees, but this was a private ceremony in which the bishop didn’t even bother to leave his train carriage. The custom then lapsed until it was revived in its modern form with the 1984 appointment of Bishop David Jenkins, with Darlington’s mayor taking on the role of Sockburn’s lord. The falchion – well, its replica, anyway – has been presented to all new bishops ever since.

A Bonus Dragon Slayer’s Tomb: the Case of the Slingsby Serpent, North Yorkshire

The three dragon slayers’ tombs above are probably England’s best-known, but I’m going to tell you of another dragon killer’s grave. Let’s journey to the edge of those mysterious uplands, the North Yorkshire Moors.

Half-a-mile outside the village of Slingsby – beside the road to the town of Malton – a huge and hideous serpent was said to inhabit a deep hole. This serpent – according to the antiquarian Roger Dodsworth (1585-1654) – ‘lived upon the prey of passers-by.’

The dragon was so feared that the road was even diverted so travellers could avoid becoming the beast’s next meal. Dodsworth wrote, ‘The street was turned a mile or so on the south side, which does still show itself if any take pains to survey it.’ By the time the Reverend Thomas Parkinson wrote his Yorkshire Legends and Traditions in 1888, it seems this kink had been ironed out – presumably thanks to the serpent being long slain.

The Slingsby Serpent – a snake with a nasty habit of snacking on travellers

The credit for dispatching this nightmarish creature is given to a knight from the local Wyvill family and his dog. Wyvill attacked and managed to kill the serpent, but in doing so received his death wound. A monument was set up to this hero in Slingsby’s All Saints’ Church. A stone effigy of the dragon slayer was placed on his tomb, with his faithful hound depicted at his feet. The dog is also said to have died due to the delayed effects of the dragon’s poison.

The Wyvill family have lived around Slingsby since 1215 and there’s indeed an effigy of a knight in Slingsby Church, bearing the Wyvill’s coat of arms. It probably commemorates the 14th-century Sir William Wyvill and there was once, apparently, a dog at the statue’s feet. This dog was, according to Dodsworth, ‘a talbot coursing’. A talbot is a – now extinct – light-coloured hound and ‘coursing’ means hunting so the memorial might have represented Sir William’s enjoyment this pastime rather than any dragon-slaying adventures.

A Wyvill effigy in Slingsby Church – does it depict a dragon slayer? The lower part of the statue, where the dog might have been, seems to have been broken off. (Photo: Slingsby Village)

One story claims the dragon was over a mile long. This, however, doesn’t tally with Roger Dodsworth’s descriptions. Though Dodsworth has the dragon living ‘in a great hole, round within’, he depicts it as ‘three yards broad and more’. Hardly big enough for a mile-long creature to curl up inside.

It’s possible, nevertheless, that locals noticed an unusual hole by the road – a pothole or sinkhole maybe – and looked for ways to explain it. Dragons have often been blamed for odd landscape features. The Lambton Worm – a dragon that once plagued County Durham – liked to wrap itself around hills. Two hills – Penshaw Hill near Sunderland and Worm Hill in nearby Fatfield – have strange ridges running around them, marks said to have been left by the worm’s body. The Linton Worm – which terrorised the Scottish borders, causing much land to become desolate – was killed by a local laird. As the worm thrashed about in its death throws, it created a range of hills, a tract of terrain now known as Wormington. Northern Scotland was once harassed by the Stoor Worm, a hideous sea serpent whose breath could contaminate plants and kill animals and humans. When the creature was finally slain, its teeth fell out – becoming the Orkney, Shetland and Faroe Islands – while its body became Iceland.

What Could Lie Behind Myths of Dragon Slayers?

We’ve already looked at a few explanations for the dragon-slaying stories above: the legends could have been invented to explain unusual tombs or landscape features, to justify claims to landholdings or to scare children away from places of danger. But, at a deeper level, what might myths of despatching dragons represent? Remarkably similar dragon-killing stories can be found in many parts of the world and across historical epochs and not all of them can be explained away by weird tombs or Norman nobles anxious to cement the ownership of their estates.

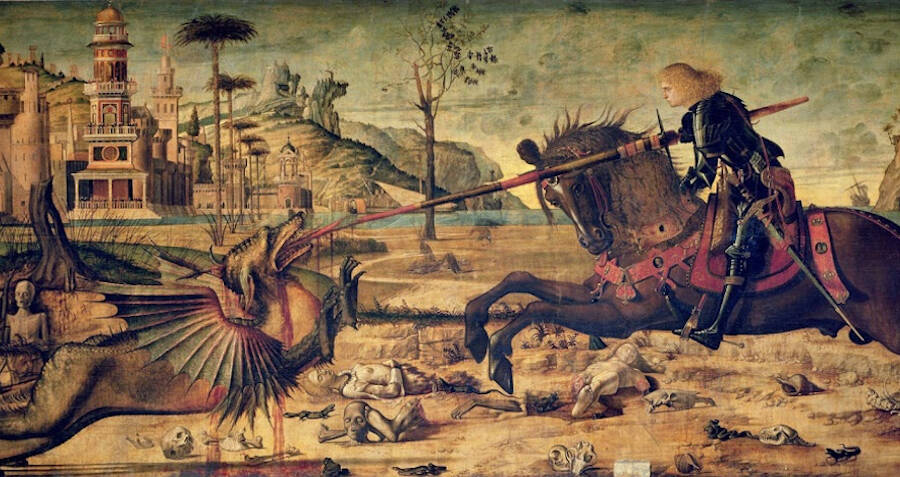

Many dragon myths are connected to two interlinked factors: water and fertility. We’re used to thinking of dragons as fiery beasts, but water plays a role in numerous dragon tales. The knuckers of Sussex lived in deep pools and the Stoor Worm appeared from the sea to cause havoc. The Linton Worm was known for skulking around a loch or bog. The Lambton worm was first pulled from the River Wear by a sinful knight fishing on a Sunday. The shocked knight cast it into a well, where – over several years – it grew to a terrifying size. The Sockburn Worm haunted a river-engirdled peninsula while the etymology of Brent Pelham links its dragon to springs. Some legends of St George say the dragon he killed came out of a lake.

St George slays the dragon in a painting by Johann Konig c. 1630. Notice the water nearby.

A common mythological pattern is the slaying of a dragon or serpent by a god associated with thunder or storms. The dragon, we’re told, has been blocking the rightful flow and distribution of water, thereby causing a drought. This harms the fertility of the land and plunges the world into chaos. A god or hero must fight the beast to restore the natural balance and get the waters flowing again. The fact a storm god usually steps up for this task is obviously connected to the releasing of water.

So, in Indian myth, we have the storm and river god Indra killing a multi-headed serpent who’d caused a drought by trapping waters in his mountain cave. In Greek myth, the serpent Typhon is chaos itself – it has a massive number of heads, many of different animals, with which it babbles a cacophony of disturbing sounds. The monster lays waste to the land, gobbles livestock, and either poisons waterways or drinks them up, turning rivers to dust and sucking seas dry. Typhon challenges Zeus for control of the cosmos, but the sky god defeats the snake with his mighty thunderbolt. Zeus buries the beast’s carcass and good order and natural balance return. The monster’s corpse beneath the earth is, though, blamed for volcanic activity. In Hittite myth, the storm god Tarhunt kills the giant serpent Illuyanka. The Norse thunder god Thor takes on the monstrous sea snake Jörmungandr, who’s destined to threaten the order of the universe during Ragnarök, the Viking Apocalypse. In the Bible, the serpent Leviathan represents the watery primal chaos upon which God imposes order by creating the world.

In the legends of dragon slayers explored in this blogpost, we can see how dragons cause chaos and threaten the fertility of the land. The dragons munch livestock, decimate crops, lay waste to whole regions and poison plants with their foul breath. Only by killing such creatures can our heroes reimpose order and make the land bountiful again.

The dragon slayer either rescuing or marrying the king’s daughter – as in Sussex – could also indicate a concern with fertility. The female (the earth) has been liberated from the monster and – now through her marriage – can be fruitful. The common motif of dragons guarding treasure or a reward being offered for slaying them is probably fertility related too. The ‘treasures’ the dragon hordes symbolise the vital waters, which need to be set free so abundance and prosperity can spread through the land. Interestingly, St George is associated with fertility, sometimes being depicted as green or surrounded by foliage. The name ‘George’ translates as ‘farmer’.

St George killing the dragon, as depicted by Vitorre Carpaccio 1502-7. Again, water is present.

Dragon legends may also reflect remnants of a darker tradition – that of human sacrifice. This can be seen in the dragon’s penchant for snaffling human beings and – especially – kidnapping or wolfing down young maidens. In Greek myth, the sea monster Cetus ravages the land and it’s felt the only solution is to chain the princess Andromeda to a rock as a sacrifice to the beast. The hero Perseus, however, turns up, kills the creature and receives the hand of the beautiful Andromeda in marriage. Such tales could represent societies moving away from the idea that human sacrifice is necessary to appease the gods and to ensure the land yields sufficient supplies.

The motif of dragon slayers dying while defeating their monsters may also have roots in these disturbing customs: the young man willingly offers up his life for the good of his community and the fertility of the land. At Ragnarök, Thor is destined to kill Jörmungandr as the serpent sprays his poison over the skies and seas. This venom, sadly, will prove too much for Thor who’ll die shortly after slaughtering the creature. Jim Pulk at Lyminster and Wyvill at Slingsby succumb to their dragons while also managing to slay them. Conyers offering up his only son to the Holy Ghost in Sockburn is a Christianised version of ideas of sacrifice.

A different take on dragon legends is put forward by the psychologist Carl Jung (1875-1961). For Jung, if I’ve understood him right, dragons represent the watery chaos of the subconscious mind, from which the ego must break free. We must, therefore, slay our dragons so we can develop mentally as individuals. This is a vital step in moving from youth to adulthood so that’s why the dragon slayers of legend are usually young. The treasure the dragon guards represents the precious potential for personal development. Entering the dragon’s dark, horror-filled cave is like plunging into the subconscious mind, from which we’ll hopefully emerge – having faced down our fears – with the riches of a profound psychological experience. Such a process might also be understood as a rebirth in the subconsciousness’s dark womb.

Jung, though, didn’t see dragons as entirely negative creatures. Serpents represent nature – albeit in a chaotic untamed form – and so can heal and nurture as well as destroy. A serpent curling around a stick or glass is a widespread symbol of medicine and it’s interesting that the water of the knucker hole at Lyminster was thought to have curative properties. Serpents, for Jung, can also transmit a primal wisdom. There’s the serpent proffering knowledge in the Garden of Eden and even Christ urged his followers to ‘be wise as serpents’. For Jung, the depiction of dragons as completely evil points to a weakness, a kind of immaturity in the fabric of Christian and Western cultures.

All this might seem a long way from worn slabs and crumbling effigies in rural churches. But perhaps these ‘dragon slayer’s tombs’ and the strange legends around them are our homely English versions of inspiring, terrifying and deeply held archetypes, archetypes of that universal, nightmarish yet ambiguous creature, the dragon.

(This article’s main image shows the face of an effigy that once decorated what was rumoured to be the tomb of the dragon slayer Sir John Conyers in Sockburn, County Durham, England. Photo: Joe Wood)

An extense and well documented article. I particularly like the psychological point of view and what the dragon signifies. I’ve always felt there isn’t enough information about them, so articles like this give light to interesting investigations.

Hi, Alicia. I didn’t know dragons were so connected to water before I wrote this article. Dragons and serpents are of great psychological importance, which is why they appear in almost every system of myth. It would be interesting to know if there are any other dragon slayers’ graves in England or in other parts of the world. Many thanks for reading the post.

The local Dragon story in my area is connected to the Bold family and an area around Runcorn and Widnes called the Halton Dragon !

I also came across several Nixen storys on the Isle of Man and visted one located in Glen Roy in a pool under a waterfall !

I’m a resident of Slingsby, but have to say that this story, from just a few miles away in Nunnington, is the better known.

https://www.mysteriousbritain.co.uk/legends/all-saints-church-nunnington-and-the-dragon-of-loschy-wood/

Thanks J, it’s a fascinating article. The story has some similarities to other dragon slaying legends, like the Lambton Worm and the Sussex ‘knucker’ tales.