On the evening of 23rd September 1954, Glasgow police received a call summoning them to the Southern Necropolis, a vast cemetery in the Gorbals, one of the city’s poorest neighbourhoods.

When PC Alex Deeprose arrived a few minutes later, he couldn’t believe the sight that confronted him.

Hundreds of children were swarming over the graveyard. Some clutched crosses and crucifixes; others brandished axes, staves and knives. The oldest kids were around 14; the youngest could barely even toddle.

PC Deeprose watched in amazement as the children searched among gravestones, peered behind trees and prowled around elaborate Victorian tombs. The scene was made even more apocalyptic by the steelworks at the end of the cemetery, which was throwing up flames, belching smoke and sending the scent of sulphur across the Necropolis.

Blasts of flame cast strange shadows; dark figures moved in and out of clouds of rolling fog. ‘There he is!’ the children would shout as they rushed off to confront some silhouette. ‘No, he’s there!’ a cry would go up as the fire illuminated another sinister outline.

PC Deeprose managed to conquer his astonishment and asked a group of children what they were doing. The kids replied they were hunting the ‘Gorbals Vampire’ – a seven-foot-tall monster with long metal fangs. They claimed the vampire had captured and eaten two boys and was living in the graveyard.

More police arrived, but they couldn’t persuade the children to give up their quest. Only when it started to rain – and a local headmaster told everyone to stop being ridiculous – did the children disperse.

The next night, however, the young vampire hunters were back, and the night after that, though in smaller numbers. But as the children’s interest in the monster waned, the Gorbals Vampire began to cause disquiet among adults.

Glasgow’s Southern Necropolis (Image: Asha Moon, Pinterest)

Parents earnestly asked the police if there was any truth in the legend. The story got into the national press, questions were asked in Parliament, and a major moral panic saw changes in the law.

But what was the Gorbals Vampire? Who was to blame for the monster’s appearance in the Southern Necropolis and what were the consequences of the creature’s ‘crimes’?

Let’s tramp through fog, sulphur and smoke and see if we can hunt down this elusive bloodsucker.

How Real Was the Gorbals Vampire?

The Gorbals Vampire certainly seemed real to the children who hunted him. On the first day of the panic, rumours of the monster spread from school to school.

Ronnie Sanderson, who was eight when he took part in the vampire hunt, said, ‘It all started in the playground.’

‘The word was there was a vampire and everyone was going to head out there after school. At three o’clock, the school emptied and everyone made a beeline for it. We sat there for ages on the wall, waiting and waiting. I wouldn’t go in because it was a bit scary for me.’

‘I think someone saw somebody wandering about and the cry went up: “There’s the vampire!”’

Another of the young vampire hunters, Tam Smith, said, ‘The red light and the smoke (from the steelworks) would flare up and make all the gravestones leap. You could see figures walking about at the back all lined in red light.’

The sighting of a bonfire near the cemetery even led to screams that the vampire was burning the remains of his victims.

Another boy there at the time, Kenny Hughes, said the children’s terror ‘built up and built up until it basically became mass hysteria.’

Despite the determination of the youngsters to hunt down their monster, there are no records of any missing or murdered children around the time of the Gorbals Vampire incident. So, if no vampire was skulking around Glasgow’s Victorian cemeteries, we might ask where such a strange myth came from.

Was the Gorbals Vampire a modern, industrial version of older legends? Were scary passages in the Bible to blame or was the culprit to be found in imported American popular culture? Were the fears of bloodsuckers just childish fantasies or was the vampire conjured from the dirt and fumes and poverty of the Gorbals itself?

Forerunners of the Gorbals Vampire – Monsters with Iron Teeth

Myths of iron-toothed monsters have haunted Glasgow for some time. According to Tam Smith, parents sometimes warned their badly behaved offspring that the ‘Iron Man’ – a local ogre – would get them.

Another Glasgow ghoul was ‘Jenny wi’ the Airn (iron) Teeth’, a hideous witch said to have prowled around Glasgow Green in the early 1800s. Jenny was infamous for devouring children who refused to sleep. A rhyme about her was told to kids who wouldn’t go to bed. Part of the poem ran:

Jenny wi’ the Airn Teeth

Come an tak’ the bairn (child)

Tak’ him to your den

Where the bowgie bides (bogie lives)

But first put baith (both) your big teeth

In his wee plump sides

An iron-toothed monster also appears in the Old Testament Book of Daniel, in which the prophet dreams of four beasts:

‘Behold a fourth beast, dreadful and terrible, and strong exceedingly, and it had great iron teeth.’

As the Gorbals had significant Protestant, Catholic and Jewish populations, it’s possible that a child could have heard about this monster at church or synagogue and told their friends. Aided by vivid imaginations and rapidly spreading whispers, youngsters could have transformed this biblical beast into the Gorbals Vampire, perhaps augmenting it with bits of Scottish urban folklore.

What Was the Significance of the Gorbals Vampire’s Iron Teeth?

It strikes me that the Gorbals Vampire’s iron teeth were its most outstanding feature.

Kenny Hughes said, ‘We were told – or we picked up in school – that it was somebody called the Man with the Iron Teeth. We started to scream, “Who’s this man with the iron teeth?” And he apparently had big fangs that come down like a walrus or something.’

I can’t help thinking that the myths of this iron-toothed monster were related to the industrial poverty of the Gorbals and the steelworks looming over it. While providing employment for some, steelmaking posed dangers to the health of its workers and put them at risk of accidents. And that’s in addition to the air, noise and light pollution the steelworks caused.

Guy Holland, from the Gorbals’ Citizens’ Theatre, said, ‘The local area at that time was dominated by Dixons Blazes, the iron foundry that would go 24/7, belching out smoke with the night sky lit up orange.’

‘There was clanking noises of metal going on and the area was polluted and smelt pretty foul – and it was directly behind the Necropolis.’

‘I think that might have had as much to do with it as anything else – kids knocking about in the graveyard at night and all the smoke and colour going on, the noise. It is a potent mix.’

Working class poverty in the Gorbals, photo by Bert Hardy, 1948 (Courtesy of E.b Phelps from pinterest)

As well as being the home of heavy industry, the Gorbals was one of Glasgow’s most poverty-stricken districts. By the end of the 19th century, the area was overcrowded and blighted by poor sanitation. Many people lived there because their firms provided worker housing and they couldn’t afford their own.

In the 20th century, as some local industry declined and unemployment grew, the area gained a reputation for crime and drunkenness. But migrants still streamed into the Gorbals from the countryside, with many arriving from the Scottish Highlands. The area also received immigration from overseas, with Irish Catholic, Jewish and Italian communities growing up. By the 1930s, around 90,000 residents were crammed into the small district, which had a population density of 40,000 per square kilometre. Such conditions bred high infant mortality and it’s worth noting the vampire was accused of killing two children.

Could the Gorbals Vampire – and earlier myths like the Iron Man and Jenny w’ the Airn Teeth – have emerged from the poverty and pollution of the Gorbals? Could they have been personifications of the hazards faced by the urban industrial poor? In the fog-laden, sulphur-tinted air, with the billowing of smoke and clunking of iron all around, could malnutrition and overcrowding have conjured up these strangely modern monsters in the inhabitants’ minds?

It’s interesting that critics of industrial capitalism likened that system to a vampire sucking its workers’ blood. In 1867, Karl Marx wrote in Capital, ‘Capitalism is dead labour, which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks.’ (Incidentally, industrial America also gave birth to a strange mythical being, a giant called Joe Magarac who stirred vats of molten steel with his bare hands.)

The Gorbals Vampire episode would go on to shake the nation, and those outraged by the incident would soon find something easier to blame – and take action over – than complex issues like poverty and industrial pollution.

The Gorbals Vampire Terrifies the Nation and the Blame Is Pinned on … Comics

Glasgow’s vampire hunt soon made it into the local press and it wasn’t long before the story was picked up by the national papers. People started searching for the cause of the hysteria that had gripped one of Britain’s major cities.

A newspaper report inspired by the Gorbals Vampire case (from the Mitchell Library)

The culprit was swiftly discovered – the American horror comics that were just beginning to get popular with UK youngsters. It was argued that these comics – with lurid titles like Tales from the Crypt and The Vault of Horror – were inflaming imaginations with their graphic images of monsters, murder and mayhem. Young minds were being ‘polluted’ by these ‘terrifying and corrupt’ publications.

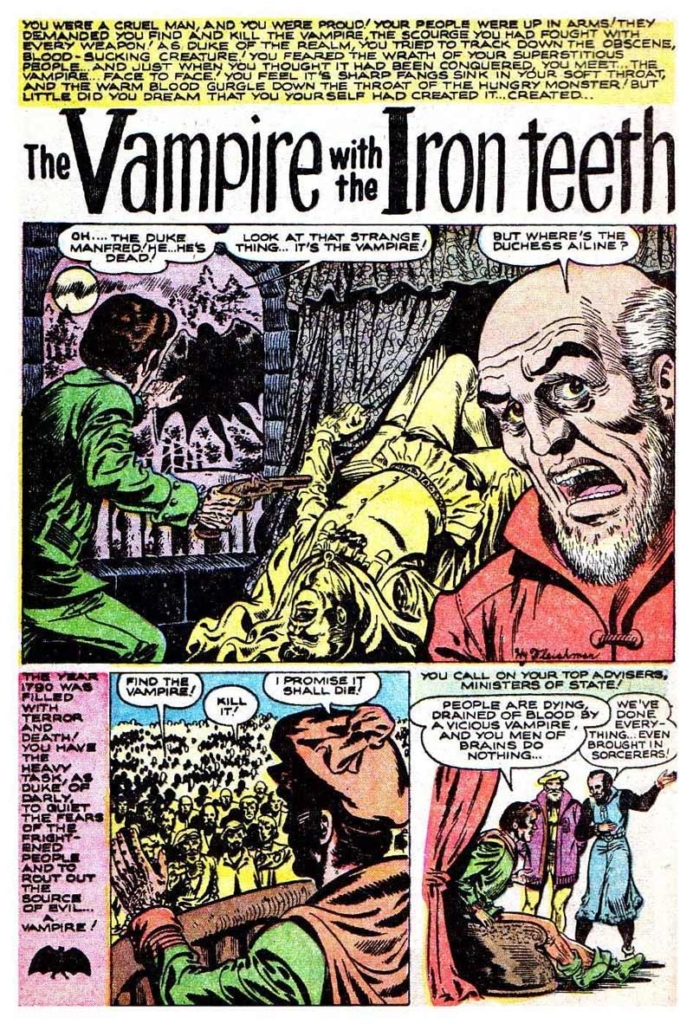

And the blame was truly pinned – or should that be staked? – on the comics when it turned out one had featured a monster similar to the Gorbals Vampire. A 1953 issue of Dark Mysteries had included a story called The Vampire with the Iron Teeth.

Did this infamous comic inspire the Gorbals Vampire hysteria? (Image courtesy of thehorrorsofitall)

A strange coalition formed to campaign against the comics, composed of teachers, Christians and – keen to limit the influence of American culture – communists. A debate took place in the House of Commons, in which the Gorbals’ Labour MP, Alice Cullen, played a prominent role. The upshot was the Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act of 1955, which banned the sale of ‘repulsive or horrible’ reading matter to children. The Act is still law today.

Were American Comics Really to Blame for the Gorbals Vampire Hysteria?

It might seem obvious that comics portraying iron-fanged vampires could spark hysteria about such creatures. But a closer examination of the facts suggests this wasn’t the case in the Gorbals.

There’s no evidence that any of the Glasgow vampire hunters had ever glimpsed an American comic. And some seemed to have had only the vaguest notions about what vampires were.

Vampire hunter Bob Hamilton admitted he had ‘no idea’ what a vampire was, saying, ‘Nobody knew we needed stakes – we didn’t have Christopher Lee to explain you had to put a stake through the heart to kill him. We were just going to cut the head off, end of story. Don’t know what we’d have done if we’d met one, like.’

Ronnie Sanderson said, ‘I just remember scampering home to my mother: “What’s the matter with you?” “I’ve just seen a vampire.” And I got a clout round my ear for the trouble. I didn’t know what a vampire was.’

Neither Ronnie Sanderson nor Tam Smith had a TV in their homes or had ever seen a comic book. According to comic expert Barry Forshaw, a British child getting their hands on an American horror comic would have been like discovering the Holy Grail.

Mr Forshaw said, ‘It was a perfect fit. Here was a campaign looking to justify itself and then this event happens.’

‘It is ironic that the moral furore began in Scotland, where the comics (like The Dandy and The Beano, published in Dundee) couldn’t have been more safe.’

Could the Vampire Have Morphed out of the ‘Magical Realist’ World Children Inhabit?

Vivid stories are invented by kids across the world, stories which often feature the monstrous, terrifying and grotesque. And the children of the Gorbals had more fuel for their fantasies than most kids. Because their neighbourhood lacked open space, they used the Southern Necropolis as a playing field.

Kenny Hughes said, ‘We’d all head off up the gravy (graveyard) – if you were out playing, you went up there.’

Spending evenings and weekends in that sprawling cemetery, in which 250,000 Glaswegians were interred; running among the huge and gloomy Victorian monuments; seeing the flames darting from the steelworks – all this may have pushed the children’s imaginations towards the macabre.

Bob Hamilton said, ‘We used to sit (up there) and tell ghost stories, scary stories.’

Children playing in Glasgow’s Southern Necropolis (Photo by Bert Hardy, 1948)

Geoff Holder, of the podcast Fortean Freak Out, said, ‘Although as adults we can sometimes reconstruct the emotional realm of childhood … we often struggle to recall the intellectual or cognitive world of the child.’

‘Perhaps young children live in a world of magical realism, where strange and wondrous things can intrude into the ordinary everyday world without causing cognitive dissonance … bizarre events can be seen as normal as children have not yet learned the ‘common sense’ limits of normality.’

Geoff argues that during the vampire hunt ‘groups of children, swept up by an intoxicating and fluid wave of exciting rumours, gathered together and engaged in a communal activity to hunt down the monster. It was enjoyable … but they weren’t playing at monster hunting, they were monster hunting.’

Geoff points out that the Gorbals Vampire episode was just one of several ‘monster hunts’ involving Glasgow children. In the 1870s, kids hunted hobgoblins in the Cowcaddens neighbourhood. The 20th century saw Glasgow youngsters hunting banshees, ghosts, maniacs and even Spring-heeled Jack, a Victorian fire-breathing phantom said to have haunted London. And such children’s hunts were not limited to Glasgow. In 1964, hundreds of Liverpool children took part in a search for leprechauns.

Geoff Holder said, ‘In some times and some places, children collectively invent threatening, uncanny or non-human figures and then engage in enjoyable collective adventures to hunt these figures down. In many cases, the hunt is ephemeral and is as quickly forgotten as any other playground sport.’

The Gorbals Vampire incident is just better remembered because it made it into the media. And the media does seem fond of chronicling the occasional yet scandalous eruptions of mythological creatures into modern life, with other famous cases including the Highgate Vampire, the Manchester Mummy, Cumbria’s Vampire of Croglin Grange, and the Cardiff Giant.

So Where Did the Gorbals Vampire Come from and What Is His Legacy?

The Gorbals Vampire seems to have arisen from a mix of ingredients – a spooky and much-frequented cemetery; the stresses caused by overcrowding, poverty and industrial pollution; and earlier legends of similar demons, which could easily be conjured back to life in such surroundings.

Add to this the tendencies of children to blur the borders of the fantastical and real, and we can see how the Gorbals Vampire emerged.

The children’s response could also be linked to a certain trait in the psyche of the Gorbals, a working-class grittiness.

Playwright Johnny McKnight, whose play The Gorbals Vampire was staged in the neighbourhood in 2016, said, ‘There is something just fascinating about the idea of primary school kids going to take on a vampire.’

‘I love that in the Gorbals, the reaction to that was: “Let’s get the bastard tonight!’”

In contrast to the moral panic of earlier years, the Gorbals now seems proud of its vampire. Residents of the district volunteered to act in McKnight’s play and – perhaps ironically – the staging of the play ran alongside a competition for local schoolchildren to create a horror comic and even design a mural in homage to the monster.

The Mural of the Gorbals Vampire in Glasgow (Photo courtesy of Travels with a Kilt)

And that mural is proudly displayed in the Gorbals today. The neighbourhood is now much redeveloped and gentrified and has lost some of its working-class edge, but I suspect the spirit of its past will be laid to rest less easily than the legend of the Gorbals Vampire.

(The main image, a statue in Glasgow’s Southern Necropolis, is courtesy of Blair DM from YouTube.)

Leave A Comment