Halloween is a time of pumpkins, fancy dress, ghost stories and horror films. It evokes the taste of apples and turnips, the annoyance of trick-or-treating kids banging at your door. But what are the origins of this spooky celebration, how has Halloween developed throughout history, and what deeper significance could this creepy festival have, both for the human psyche and our society at large?

Halloween occurs at a point on which the whole year pivots. In Europe and most of North America, at least, the summer’s warmth has faded, the evenings are growing dark earlier and an autumnal chill is snapping in the air. It’s a point at which time slips from one segment of the year into another, a no-man’s-land of the calendar in which normal rules are suspended and the usually rigid borders between rowdiness and order, fantasy and reality, good taste and bad, and even the realms of life and death become blurred.

Explore with me as I hold my jack ‘o’ lantern aloft, peer into the year’s gathering darkness and do my best to shed light on the otherworldly history of Halloween.

Samhain and Halloween’s Misty Origins in Celtic History

Halloween seems to have begun among the pre-Christian Celtic peoples of Ireland and Great Britain. 31st October was, for them, a great festival of the dead. At this juncture in the year, it was believed the walls separating this life from the Celtic Otherworld became so thin that the souls of the departed could pass through them to visit their living relatives and warm themselves in their old homes. Less benevolent spirits were also unleashed from the Otherworld and had to be appeased or expelled.

Samhain, as the Irish called Halloween, was also a fire festival. Fires were put out and ceremonially relit – from, some assert, sacred flames guarded by druids – symbolically marking the turning of the year as winter approached. And Samhain was a turning point in another way. At this time, cattle were brought in from their summer grazing grounds and chosen for slaughter or breeding – an event of massive importance in a pastoral society.

During this period of history, Halloween had a dual character. On the one hand, it was a time of celebration. People were well-fed after the summer and autumn; barns and storehouses were full. It was a time of homecoming for shepherds, sailors and warriors, a time for reunions, stories and celebrations, hence Halloween’s festive aspects. But Halloween also heralded winter – darkness, cold, discomfort, sickness, claustrophobia and possibly death were on their way. This could have contributed to the belief that evil spirits were let loose and the mocking of them – through masks, games and costumes – could have helped people confront their terrors.

Halloween was considered a time for divination, a belief that has lingered even into our modern age. Perhaps people had the idea that at this pivotal point the barriers between the present and future were porous. These divinations were often concerned with love and marriage, but also with death – especially with who would make it through the winter. One Scottish custom involved the placing of stones around a bonfire, each representing a family member. If any of the stones were found to have disappeared the next day, it was believed the person they represented would soon die.

But how did this pagan festival, celebrated in the wet and blustery fringes of northern Europe, spread throughout the Western world and beyond? Much of the next chapter in the history of Halloween bears the weighty inscription of the Catholic Church.

Just the Thinness of a Shroud Separates Us from the Dead. Samhain Morphs into All Saints and All Souls

Elsewhere in Europe, feasts for the dead tended to occur in spring. For example, Lemuria and Rosalia, Roman festivals for the departed, normally took place in May. Wishing to Christianise these pagan traditions, the Church first introduced the Feast of All Saints on November 1st then later All Souls on November 2nd. Perhaps the Church tried first to redirect pagan veneration of the dead to deceased saints then when this didn’t catch on decided to dedicate the next day to all dead Christians.

But the reason for the Church siting these festivals around the time of Halloween is something of a mystery. The celebration of All Souls seems to have begun in the Cluniac Monastic Order around 1000 AD – where perhaps there was some Celtic influence – before spreading throughout Europe. Maybe the Catholic Church wanted to distinguish itself from the Orthodox Church, which celebrated – and still celebrates – its All Souls’ Day in spring. But, whatever the reason, All Souls took root and came to be observed across the Catholic world. (The term ‘Halloween’ derives from ‘All Hallows Eve’, meaning the day preceding the holy festivals of All Saints and All Souls.)

Various customs associated with All Souls showed reverence to the dead, stressed connections between the dead and living, and helped people face up to their own mortality. Some of these traditions assumed – as had Samhain – that shades would return to their old homes. In Brittany, cider and food were set out in cottages for visiting souls and fires kept burning all night to guide and warm them. Musicians toured villages, singing dolefully. In the Tyrol Mountains, ‘soul lamps’ were placed on hearths, filled with butter and lard so spirits arriving from purgatory could soothe their burns with these substances. (The rise of the doctrine of purgatory, where souls had to be purified in a temporary hell before they entered heaven, was a powerful factor in the popularity of All Souls). People across Europe ate special biscuits called soul cakes and some believed that each cake you ate released a soul from purgatory. Masses and prayers were offered up to help the dead on their journeys through that realm.

All over Catholic Europe, All Souls is an important festival today. Graves are decorated and cleaned, candles and lamps placed on them. Cemeteries and churchyards twinkle with lights in the evening.

The Feast of All Saints/All Souls in Cracow, Poland (Photo courtesy of inyourpocket)

Much of this was swept away in the Protestant Reformation (~1517 – 1650), with the reformer Calvin claiming, ‘The service for the dead is a kind of witchcraft’. The half-way house of purgatory was replaced with the strictly dual destinations of heaven and hell. But while this, of course, affected Catholic Ireland much less than Protestant Britain, even in Britain Halloween customs lingered on, especially in Scotland, Wales and northern England. In Scotland, until the end of the 18th century, people celebrated Halloween by dragging flaming tar barrels through the streets and lighting fires, called Samhnagen, on hills. On the Celtic Isle of Man, fires were kindled for protection against fairies and witches.

Such customs would prove strong enough to skip across the Atlantic and the transplantation of such traditions forms the next part in the long history of Halloween.

Halloween Crosses the Pond – Ghosts, Pranks, Whispering Breezes and Misrule

Scots and Irish immigrants brought Halloween customs to America, where they took root and combined with traditions from other migrant cultures – German witchcraft lore, English and Dutch masquerades, additional superstitions about witches and black cats brought by African slaves, and practices from the Mexican Day of the Dead. These customs developed differently in different areas. On Halloween, in the Virginian Mountains, people claim you can hear the future whispered on the wind; in Louisiana, it’s said that if you cook a meal in silence and stir it anti-clockwise, a ghost will slip in and sit at the table.

There’s also the idea that Halloween is a time for pranks and misrule, as if at this turning point, in this interspace between the year’s two halves, ordinary regulations and laws are suspended. American newspapers from the late 1800s reported Halloween pranks such as exploding pipe bombs, human corpses being hung in front of butchers’ shops, flour attacks on trams, ropes being strung across pavements to trip the unwary, the streets of an island being filled with boats and even attempts to jack up churches. Such disorder has continued into modern times. In 1984, 810 fires were started on Halloween in Detroit. In 2015 in London, police were telling shopkeepers not to sell eggs and flour to kids and an anarchic ‘ride-out’ of bikers in the south of the city caused much apprehension.

The somewhat gentler tradition of ‘trick-and-treating’ evolved over the centuries. A custom of ‘souling’ developed in the Middle Ages, which involved poor people asking for gifts of food on All Souls’ Day. (The poor were probably seen as stand-ins for the dead.) Souling gave way to ‘mumming’ or ‘guising’ traditions. These customs involved people dressing in costumes, visiting houses, and reciting poems, songs and jokes in return for food or drink. Guising degenerated into the practice of obtaining sweets by threatening householders with pranks. The first known mention of the term ‘trick or treat’, however, doesn’t occur until 1927, in the USA.

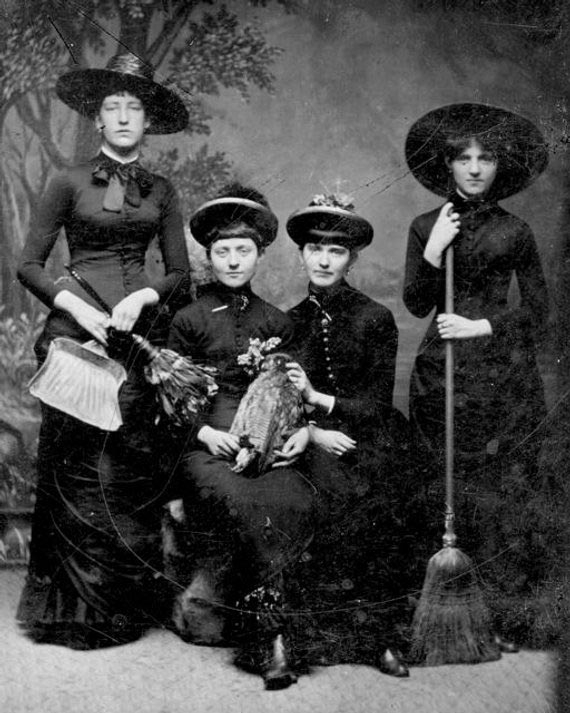

As American society evolved, so did its customs, Halloween included. The festival grew in popularity during Victorian times, partly due to the influence of gothic novels like Dracula and Frankenstein. The festival also became popular thanks to Victorian Americans linking Halloween with the rural, traditional and folkloric, and seeing it as a welcome relief from the factories and urban squalor of their increasingly mechanistic age.

The popularity of gothic novels helped boost Halloween in the US in the Victorian age

By the early 20th century, the super-rich capitalist class was celebrating Halloween with glitzy society parties, with the Rockefellers and Vanderbilts holding events in prestigious New York hotels. But more populist and democratic American instincts were also apparent, with parties and parades organised by civic groups in areas like Venice Beach and the Bronx.

During World War II, and especially in the 1950s, Halloween was seen as more for kids. Attempts were made to calm down and civilise Halloween and move celebrations off the streets into the home, reflecting the suburban, bourgeois, family-raising character of the era. A more sanitised trick-and-treating became widespread in the US, with suburbs considered safer places for kids to wander around after dark.

In the 1950s, Halloween was seen as a children’s festival

A Lot Changes But Something Stays the Same – Halloween in the Age of Turbo-Capitalism and Globalisation

The more recent history of Halloween has reflected the rapid social changes of the modern Western world. The growth in US Christian fundamentalism since the late seventies can be seen in ‘Hell Houses’ – alternatives to the commonplace American Halloween haunted house attractions – which try to scare the unrepentant with gory visions of the afterlife. The turbo-capitalism which has been surging in the West from about the same period has, of course, profited from Halloween. It’s estimated that in 2018 UK shoppers spent around £419 million on the festival, a number dwarfed by the whopping $9 billion Americans splashed out. The Sexual Revolution has led to the popularity of sexy Halloween costumes, cross-dressing (actually, a tradition with a long pedigree at this subversive time of year) and gay Halloween parades.

The dominance of Hollywood, and the rise of the horror movie, has added a terrifying, gore-tinged element to the festival, something that Halloween, while always spooky and otherworldly, didn’t traditionally have. Multi-culturalism and globalisation are also evident. American Halloween has been mingling with the Mexican Day of the Dead, with Mexican shops selling ghost masks, vampire fangs and witch costumes and American bakeries stocking sugar skulls, sometimes annoying cultural purists on both sides of the border.

American Halloween has spread to Europe and beyond, including back to its original homelands of Britain and Ireland, where it has mingled with older, indigenous traditions. Indeed, there have been complaints in Scotland and northern England of American pumpkin lanterns supplanting the traditional turnip ones. The success of Halloween is even seen as a sign of American hegemony – in 2005, Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez called for a ban on a popular ‘Zombie Walk’ in Caracas, saying Halloween was ‘a US custom that attempts to frighten in the same way US policies do to other countries.’

Like many aspects of culture, Halloween represents a society’s anxieties and hopes in any given period. Perhaps the West’s rather clinical, hands-off approach to death has resulted in more curiosity about it, with Halloween a means of both acknowledging mortality and mocking its terrors, just like in ancient times. This may be why Halloween is often stronger in traditionally Protestant nations than Catholic ones, where All Souls’ Day still has an influence. In our confused and worry-ridden epoch, perhaps old Samhain is reasserting its former purpose.

Throughout Halloween’s history, from its obscure Celtic origins to our post-industrial age, this creepy festival has somehow managed to respond to the profoundest human needs. It will be fascinating to see how Halloween reshapes itself to deal with the changes, challenges and stresses of the future.

Leave A Comment