Late one moonless, starless evening, probably sometime during the 1500s, an isolated inn high on a bleak moor had just shut up for the night. A cautious rapping sounded on the inn’s door and the owners opened it to reveal what appeared to be an aged beggar man. Stooped and seemingly frail, the man was swathed in a threadbare cloak and hood, a garment soaked and dripping from a recent downpour. His white hands – trembling with cold – poked from its frayed sleeves. In a piteous voice, the man asked if he might have a night’s lodging and the inn’s owners – being compassionate souls – agreed.

Beckoned into a large room and given a seat near the fire, the man warmed his icy hands and his shivering subsided. Apologising that there were no spare rooms, the owners said the beggar could spend the night on the rug, where the embers of the blaze would at least warm him for a time. Profusely thanking the landlord and landlady, the man accepted their offer.

Everyone soon retired to bed, but the maidservant – having remembered one last chore – crept into the kitchen. She walked on tiptoes so as not to disturb the beggar, who she thought would be asleep in the large room, which the kitchen opened onto. But, glancing in there, she saw something that made her gasp – a gasp she only just managed to stifle.

The man had drawn himself up from the rug. Now standing straight, he was clearly neither weak nor old. The man confidently sat down at a table, reached into the pocket of his cloak and drew out a strange object – an object that resembled a withered, disembodied hand. He wedged the hand into a nearby candle holder and daubed some liquid on each finger and the thumb. Stepping over to the fire, the man lit each of these digits, digits that then burned like candles.

Trembling, her heart pounding, knowing the man must have some evil intent, the maid sneaked out of the kitchen and up the stairs to wake the household’s other members. Entering the room of her master and mistress, the maid shook them vigorously, but couldn’t rouse them. She’d never seen anyone sleep so profoundly – it was as if some spell had locked them in the world of dreams. Despairing of waking them, she scurried into the room of their oldest son, but he too was deep in the same enchanted slumber and no amount of shaking, slapping or even pinching could make him stir. It was the same with the other children and with all the servants so – heart bashing, mind whirling – the maid crept back downstairs.

Hiding again in the kitchen, she watched the beggar walk around the large room with an open sack. He picked objects up, examined them leisurely and dropped anything he seemed to think valuable into the bag. The hand stood on the table, its fingers blazing with an eerie light, but the maid noticed the thumb was lacking any flame. The man saw this too and tried to relight it, but the thumb wouldn’t ignite, making the man scowl and swear. (If any person remains awake in a household then one digit of the Hand of Glory – as the thief’s macabre implement was known – will stay unlit.)

Hastening a little now, the man picked up the burning hand and walked towards the door that led to the next room. The girl at least knew he wouldn’t get in there – that door was locked and the key well-hidden. But she was amazed to hear a click and see the man effortlessly push open the door. Placing the Hand of Glory back on the table, the man picked up his sack and entered the room he’d just unlocked, leaving the door ajar behind him.

Now certain the hand was some instrument of devilish magic, the maid sneaked from her hiding place and grasped the candlestick. She tried to blow the fingers out, but couldn’t extinguish them. Hurrying with the Hand of Glory into the kitchen, she poured beer over it, but this just made the fingers burn brighter. She seized a jug of water and tipped it over the talisman, but the flames barely faltered.

The maid was panicking now – the floor was creaking, the metal clinking in the man’s sack as he walked back towards the large room. She grabbed a jug of milk and – as a last resort – drenched the hand with it. With a fizzle, all four fingers went out. Dashing back into the big room, she snatched the key from its hiding place and locked the thief in the room he’d entered.

The hush that lay over the house shattered. The horrors the maid had witnessed broke from her throat in screams; the man was shouting, cursing, barging at the locked door, trying to knock it down. The landlord, his sons and servants came charging in from their bedrooms, the thief was apprehended and it wasn’t long until he was dangling on the gallows.

That’s the story, anyway, that was told to the folklorist Sabine Baring-Gould by a Yorkshire labouring man, probably in the late 1800s. The story seems, at that point, to have been old and widespread. Very similar accounts appear in William Henderson’s Notes on the Folklore of the Northern Counties of England and the Borders (1866) as well as in Disquisitiones Magicae (1593) by Martin Anthony Delrio.

But what exactly was the Hand of Glory? What uncanny powers did folklore ascribe to this grisly object and how might a thief or bandit with a side-interest in the occult go about acquiring or making one? If you suspected someone wanted to use a Hand of Glory against you, how could you defend yourself? As well as hands, could other bewitched body parts be of aid to the enterprising villain and how might the thoroughly weird beliefs around the Hand of Glory have grown up in the first place?

Let’s embark on a strange and gruesome journey past gibbets and gallows, pausing along the way to peruse popular books of magic, to examine the enchanted droppings of ravens, and to watch priests bless severed fingers. And I might just let slip where a person with a macabre curiosity and robust stomach could get a glimpse a genuine Hand of Glory today.

What Was the Hand of Glory?

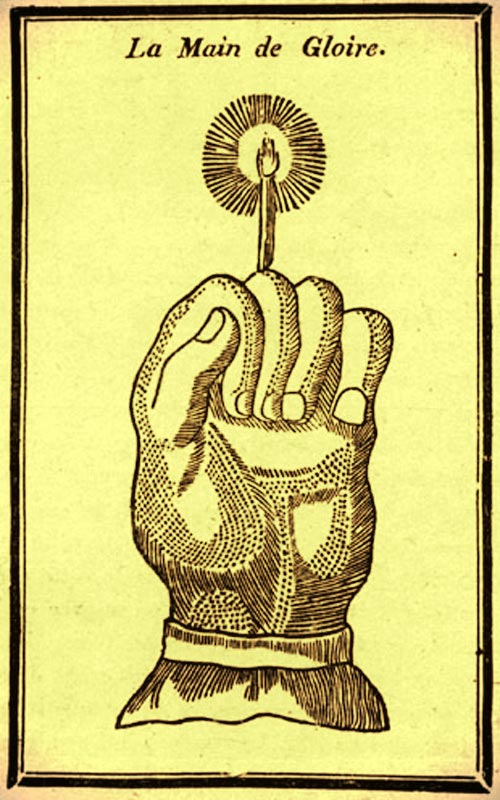

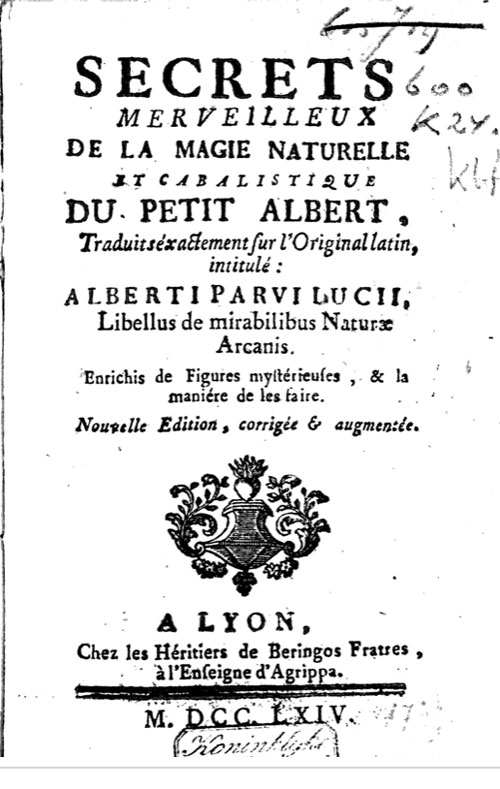

A Hand of Glory was a severed, preserved hand of an executed criminal. The left hand (the word ‘left’ was once synonymous with ‘sinister’) was generally preferred. If the man, however, had been hung for murder, the hand that ‘had done the deed’ was usually chosen. The Hand of Glory gets a mention in the Petit Albert (Little Albert), an 18th-century French compendium of folk magic, alchemical lore and Kabbalistic enchantments, which was widely translated and distributed across Europe. According to the Little Albert, this is how you can create your very own Hand of Glory:

‘Take the right or left hand of a felon who is hanging from a gibbet beside a highway; wrap it in part of a funeral pall and so wrapped squeeze it well. Then put it in an earthenware vessel with zimat, nitre, salt and long peppers, the whole well powdered. Leave it in this vessel for a fortnight then take it out and expose it to full sunlight during the dog days (the hot, sultry days of July and early August) until it becomes quite dry. If the sun is not strong enough then put it in an oven with fern and vervain.

Next make a candle from the fat of a gibbeted felon, virgin wax, sesame and ponie, and use the Hand of Glory as a candlestick to hold this candle when lighted, and then those in every place into which you go with this baneful instrument shall remain motionless.’

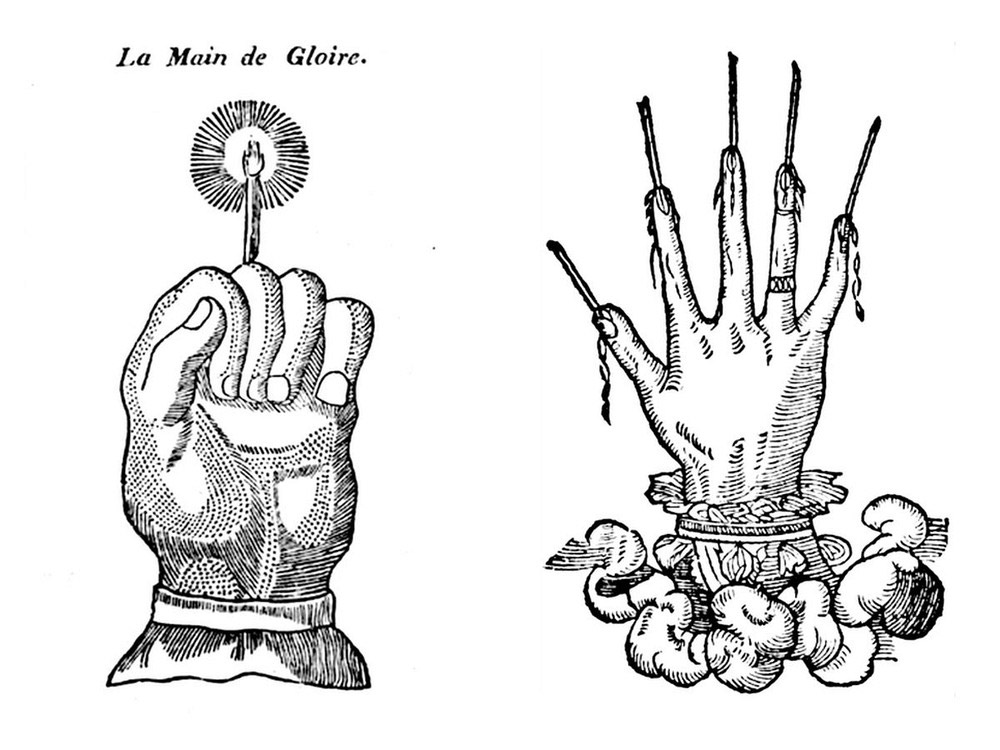

A Hand of Glory in the popular grimoire – or book of magic – known as the Petit Albert (Little Albert)

Notwithstanding the Little Albert’s helpfulness, there was some debate about its instructions. Did ‘ponie’, for instance, refer to horse dung or was it a type of sesame? It’s disputed whether the original French was du siseme et de la Ponie (horseshit) or du siseme de Laponie (sesame of Lapland). Did zimat mean verdigris (a green pigment) or Arabian sulphate of iron? It’s easy to imagine an apprehended thief cursing their decision to substitute sesame seeds for horse manure or bitterly lamenting their choice of green pigment over iron sulphate when preparing their precious Hand of Glory.

Even more confusingly, the Little Albert wasn’t the only authority on how to manufacture this macabre tool and different sources gave differing advice. In Whitby Museum, North Yorkshire, a genuine Hand of Glory is on display. This hand – leathery and long-fingered, its digits leached (or burnt) white – was found hidden in a thatched cottage and is thought to have come from the appropriately named Gibbet Howe, near the Yorkshire village of Castleton. The hand is exhibited with a page from a book published in 1823, which obligingly offers directions on creating a Hand of Glory:

‘It must be cut from the body of a criminal on the gibbet, pickled in salt, and the urine of man, woman, dog, horse and mare; smoked with herbs and hay for a month; hung on an oak tree for three nights running, then laid at a crossroads, then hung on a church door for one night while the maker keeps watch in the porch – and if it be that no fear hath driven you from the porch … then the hand be true won and it be yours.’

A genuine Hand of Glory, in Whitby Museum, Yorkshire. (Photo: badobadop)

But from all the above sources, we get the general idea: a hand must be hacked from an executed convict, somehow preserved and made to produce light, either from its own fingers or by gripping a candle made from an executed felon’s fat. The Hand of Glory’s darkly miraculous powers range from throwing people into unwakeable sleeps to rendering people immobile to unlocking doors, all assets highly useful for those bent on burglary.

But what should you do if you suspect a criminal with a sideline in witchcraft is plotting to use a Hand of Glory? As we’ve seen in the story above, milk seems the only liquid capable of putting the dreadful candles out. If you’d, however, prefer not to get to the desperate stage in which the maid found herself, you can take preventative action. Once again, the Little Albert proves helpful:

‘The Hand of Glory would become ineffective, and thieves would not be able to utilise it, if you were to rub the threshold or other parts of the house by which they may enter with an unguent composed of the gall of a black cat, the fat of a white hen, and the blood of a screech owl; this substance must be compounded during the dog days.’

So now you know. If you have any thieves in your locality with a penchant for the occult then searching out black cats, white hens and screech owls may be more effective than investing in a burglar alarm.

The Strange and Macabre Folklore of the Hand of Glory

The folklore around the Hand of Glory seems to have been fairly similar in a number of parts of Europe. In his A Provincial Glossary, with a Collection of Local Proverbs, and Popular Superstitions (1787), Francis Grose stated that belief in the malevolent powers of the Hand of Glory was widespread across France, Germany and Spain. Grose mentions a foreign judge who told him he’d been present during the torture of criminals who’d admitted using the hand.

The criminals confessed to making the Hand of Glory in a similar way to that prescribed by the Little Albert. They said the hand should be ‘cut from a gibbeted person and wrapped in a piece of shroud or winding sheet’. The hand must be ‘well squeezed to get out any small quantity of blood that may have remained in it, then put in an earthenware vessel with zimat, saltpeter, salt and long pepper.’ The hand should be dried ‘in the noontide sun in the dog days’ and should be used to hold a candle ‘made with the fat of a hanged man, virgin wax and the siseme of Lapland.’ The malefactors also confirmed that an antidote to the ‘dreadful instrument’ could be made from ‘the gall of a black cat, the fat of a white hen and the blood of a screech owl’.

The cover of the Petit Albert (Little Albert), which promises an insight into the ‘marvellous secrets of natural and Kabbalistic magic’.

The folkloric tales concerning the Hand of Glory have many similarities too. One night in 1797, a hunched and feeble old woman appeared at the Inn of Spital on Stanmore, a high and lonely hostelry run by George Alderson and his wife and son, with the help of their maid Bella. When they heard the crone’s hopeful tapping, the Aldersons had already barred the inn’s sturdy door, and were seated around a crackling fire, discussing a substantial amount of money they’d recently made at a fair at Broughton Hill. Opening the door, they immediately took pity on the woman, especially as a freezing wind was moaning around the inn and whipping stinging rain about.

The woman, dressed in a long cloak and hood, tottered into the warm room as water dripped from her garments, leaving pools on the oaken floor. Though shivering violently, she refused to take off her cloak and have it dried and also declined all offers of food and drink. She said she merely wanted to sleep a little in a chair by the fire and that she’d let herself out and resume her journey as soon as daylight came.

The family went to bed and Bella was left with the old woman. The maid’s attempts at conversation met with little more than single words and grunts, but Bella did notice the woman had an unusually gruff voice. When the woman stretched her feet towards the fire, Bella saw she wore horseman’s gaiters under her long skirt. Deeply suspicious, Bella yawned and stretched, feigning exhaustion. She lay down on the sofa and pretended to fall asleep, but kept her eyes open a crack.

A few minutes into Bella’s mock slumber, the figure in the chair stood up. Frail and stooped no more, the person now seemed to Bella a powerfully built man. Delving into his cloak, the man tugged out what looked like a withered hand. Reaching into his cloak again, the man produced a candle, lit it on the fire and wedged it in the hand’s grip. The stranger stepped towards Bella and leant over her. Though she quickly scrunched her eyes shut, Bella soon had the impression the villain was waving the candle in front of her face. The man chanted an incantation:

‘Let those who rest more deeply sleep,

Let those awake their vigils keep.’

Creaks on the floor indicated the man had turned and stepped away from her so Bella opened her eyes a notch. She watched the man place his Hand of Glory on the table as he murmered the next part of his charm:

‘O Hand of Glory shed thy light;

Direct us to our spoil tonight.’

The man walked to the window, lifted the curtain and peered outside. Apparently satisfied with what he saw he went on:

‘Flash out thy blaze, O skeletal hand,

And guide the feet of our trusty band.’

The flame of the candle shot up and blazed brightly, producing an unworldly light which filled the whole room. The man walked to the door, unbarred it and took a few steps outside. He pulled a whistle from his cloak, which he then blew. Grasping this opportunity, Bella rushed to the door, slammed it shut and slid the bar in place, locking the man out. Running to the bedrooms, she tried to rouse the family, but they all seemed in the deepest slumber and didn’t respond at all no matter how much she shook them and yelled. There now came shouts from outside. Fists were bashing, and shoulders barging, the door; hands were shaking the sash windows. Guided by the glow of the gruesome candle, the rest of the criminal gang must have arrived.

Bella raced back into the main room. Seeing the Hand of Glory burning, she realised the weird implement was the cause of the family’s abnormal sleep. The bandits outside were screaming threats; the stout bar on the door was bending, splintering, as the men repeatedly threw themselves against it. Glancing around in panic, Bella spotted a jug of milk and poured it over the hand. The flames hissed out; seconds later George Alderson and his son hurtled into the room in their nightclothes, clutching firearms. Flinging open a window, the son fired into the darkness.

‘Give up the Hand of Glory and we will not harm you!’ a voice called out.

In answer, young Alderson fired again. There was a groan and the thieves fled. The next morning, the family noticed a trail of blood that ran for quite a distance. The Hand of Glory stayed in the Aldersons’ possession for the next 16 years.

This story appears in About Yorkshire (1883) by Thomas and Catherine Macquoid. The authors claimed that one of their informants, a Mr Atkinson, was told the tale by Bella herself when she was an old lady.

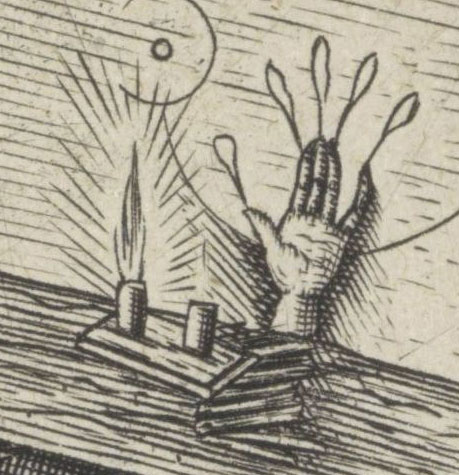

A Hand of Glory in the 1565 artwork ‘The Elder St Jacob Visiting the Magician Hermogenes’ by Pieter van der Heyden

Another story has two magicians cadging a night’s lodgings in a pub. Distrustful of the strangers, the maid spies on them through a keyhole and sees them producing a Hand of Glory from a sack. The magicians anoint the fingers with a mysterious potion and light them like candles. Only the thumb won’t burn because the maid is still awake. While the thieves are trying to break into her master’s strongbox, the girl grabs the hand and blows the candles out. The family – who’ve been trapped in a magical sleep – swiftly wake up.

In a story from Huy in the Netherlands, two miscreants beg a bed for the night before sparking up a Hand of Glory. The maid, however, stays awake, a fact indicated by a tell-tale finger that won’t light. She soon seizes the morbid candelabra and blows out its flames. Her master and the manservants come bounding from their beds and drive the villains off.

These accounts all have a similar pattern – thieves, sometimes in disguise, request a night’s shelter before trying to rob the family using the baleful hand. They’re foiled by the maid, who manages not to fall asleep and – often with the milk jug’s help – extinguishes the instrument of enchantment. The thieves are captured or chased away and never succeed in their attempts at burglary.

Though similar tales about the Hand of Glory were widespread across Europe, we might ask if it was only dead men’s hands that criminals used as supernatural aids. Other magical body parts were indeed sometimes employed by those seeking to rob, cheat and steal as the next section will show.

Ravenstones, Felons’ Feet and Fingers of Sin – Gruesome Alternatives to the Hand of Glory

Tales from Continental Europe suggest that other dubiously acquired body parts were seen as having similar properties to the Hand of Glory.

An account from the Netherlands has a thief being arrested near Bailleul. When searched, the thief was found to have been carrying the foot of a hanged man, which – like the Hand of Glory – had the power to put people to sleep.

Sometimes just a finger seems to have been enough. Also in the Netherlands, in a village called Alveringen, there once lived a sorceress who owned a thief’s finger. The sorceress had got the village priest to empower this dastardly digit by reading a total of nine masses over it. She’d wrapped the finger in cloth and persuaded the sacristan it was a holy relic, which the priest was then happy to bless. Though just a single finger, the dismal talisman seems to have had all the powers of a full Hand of Glory as the sorceress would use it to send people to sleep before pilfering their possessions. But, like all those who use such morbid relics, she was eventually found out and the stolen items were recovered from her home.

Another tale concerning a finger comes from Poland. In Pomerania, a tavern owner possessed a finger of sin – a preserved finger from an executed felon. The wily publican kept this finger in his casks of drink and – because of the detached digit’s baleful powers – his establishment was always thronged and he grew wealthy. One day his servant, when cleaning out a cask, was shocked to discover the bleached wrinkled relic. The servant reported his master to the authorities and the publican was given a long prison sentence. After getting out of jail, the man tried to re-establish his tavern, but – due to his reputation for dabbling in the occult – customers avoided his bar. The man went bankrupt and became a beggar.

In Germany, thieves made use of objects called ravenstones. Ravens were infamous for feasting on the corpses of gibbeted convicts. Ravenstones were the undigested remains of criminal’s eyes picked out of ravens’ droppings. Supposedly, ravenstones gave off a light only their owners could see.

Thieves’ Lights – An Even More Repulsive Practice

An especially horrifying variation on such customs was found in Germany – the practice of making so-called thieves’ lights. Thieves’ lights were candles formed from the body parts of unborn, unbaptised babies. The lights were especially effective if the mother had been an executed felon. The poet and historian Ernst Moritz Arndt (1769-1860) wrote in his Der Rabenstein:

‘It is gruesome to relate how thieves’ lights are obtained. They are the fingers of unborn, innocent little children. For these purposes, the fingers of already born and baptised children cannot be used …

When a female thief or murderer hangs or drowns herself, or is hanged or beheaded, and she is carrying a child inside her body, then you must go forth at midnight on the Devil’s roads, not on God’s roads, with incantations and magic, not with blessings and prayers, and you must take an axe or knife that has been used by an executioner, and with it you must open the poor sinner’s belly, take out the child, cut off its fingers and take them with you.

But this absolutely must all be done at midnight in the most perfect solitude and silence. Not even the softest sound, no “oh” and no sigh can escape the lips of the seeker.’

These gruesome lanterns would supposedly ignite whenever and wherever their owner wished, would burn for him and no one else, make him invisible and enable him to see even in the thickest darkness. The owner could also put them out with just one thought. No matter how many times it was used, the finger wouldn’t burn down but would stay the same length. Like the Hand of Glory, thieves’ lights put people into a deep sleep. According to Arndt, a bewitched individual wouldn’t wake even if you ‘set off ten thunderbolts over his head’.

Fingers weren’t the only parts of unborn children that could be used in this way. The German folklorist Jakob Grimm (1785-1863) wrote that a talisman known as a thief’s thumb – the thumb of an unbaptised child – was reputed to have similar effects to the Hand of Glory.

The toes of such infants could also be utilised for wicked purposes. A story from Germany has an old vagrant begging a night’s lodging from a widow. But, unlike in the stories above, this beggar proves to be a hero rather than a criminal. Hearing a noise, the beggar wakes to see three men – their faces painted black – moving through the house clutching strange candles. The beggar murmurs a spell, the men’s candles are extinguished and they find they can’t move. Their face-paint scrubbed off, the villains turn out to be in-laws of the widow. Their mysterious lanterns had been made from the toes of unborn children.

In Swiss folklore, the whole hand of an unbaptised child could be employed for villainy. Like with the Hand of Glory, one finger wouldn’t burn if anyone in the house was awake. Apparently, in Switzerland it was the practice to bury unbaptised babies at night in unmarked graves so no one would be tempted to put their remains to such unholy uses.

Indeed, some tales suggest criminals would go to incredible lengths to acquire these nefarious trophies. In Germany, it was alleged bandits would buy pregnant women for high prices so their babies’ fingers could be made into thieves’ lights. In one story, the serving girl of a miller is with child. Her fiancé, coming to visit one night, sees a covered cart outside the house and hears a groan from inside the wagon. The fiancé peers through the miller’s window and sees him counting a pile a coins in front of a group of suspicious-looking men. Climbing into the back of the wagon, the fiancé finds his intended gagged and bound. He carries her off and – from a hiding place – they watch the jubilant bandits drive away, convinced they’ll be enriched by their malignant talismans.

What Could Explain the Strange Customs and Beliefs around the Hand of Glory?

We might ask why criminals – and much of the general populace – believed the Hand of Glory could imprison people in sleep and make locks spring open. The strange notions around the hand – and similar gruesome artefacts – seem to have arisen from a weird mix of entrenched folklore, gallows superstitions and misunderstandings of ancient books. Keep reading for tales of gibbets, sun-bleached bones said to cure arthritis, midwives acting as undertakers, and dead convicts’ hands healing beautiful women.

Many Believed Relics from Executions Were Imbued with a Potent Magic

In many parts of the world and across different periods of history, there’s been a sense that objects linked to executions have magical or healing powers. Accounts of public executions in London speak of the crowd scrambling to hack pieces from the hangman’s rope or tear scraps from the dead felon’s clothing. Those fighting over these morbid souvenirs presumably either wanted them for their own superstitious purposes or were keen to sell them for a substantial sum.

Murderers were often gibbetted, meaning their rotting bodies were suspended – sometimes for years – in a cage or chains from a gallows-like structure as a warning to others. Gibbets could be a target for those seeking items of folk magic or medicine. The bones of one John Breads, whose body was hung up on Gibbets Marsh near Rye, Sussex, were stolen by old women who believed they could help their rheumatism. Wooden splinters from Winter’s Gibbet in Northumberland were famous for curing toothache.

The popular imagination seems to have, especially, imbued the hands of the executed with strong powers of enchantment or healing. An account by a Frenchman of a London execution tells of a sickly ‘young woman, with an appearance of beauty, all pale and trembling, in the arms of the executioner, who submitted to have her bosom uncovered in the presence of thousands of spectators and have the dead man’s hand placed upon it.’ In the mid-1600s, the severed hand of an executed criminal could fetch the price of ten guineas as ‘the possession of the hand was thought to be of still greater efficacy in the cure of diseases and the prevention of misfortune.’

It’s not surprising, then, that the Hand of Glory – cut from an executed, often gibbetted, criminal – was seen as a magical instrument. But what might explain the specific powers ascribed to the hand – its abilities to shed an eerie light, pick locks, make people immobile and cast them into the deepest sleep?

The Hand of Glory’s Weird Powers – Sympathetic Magic and the Ominous Mandrake Plant

There was probably some sympathetic magic going on with the notions around the Hand of Glory. The dead man’s hand made people temporarily ‘dead’ – by throwing them into a ‘deathlike’ sleep and rendering them as immobile as a corpse. There was also the fact that the hand had belonged to a criminal. Magically empowered by the execution its owner had gone through, the criminal’s hand – villains may have reasoned – would have been adept at criminal acts like picking locks. But the hand’s alleged ability to glow with a weird light is harder to explain.

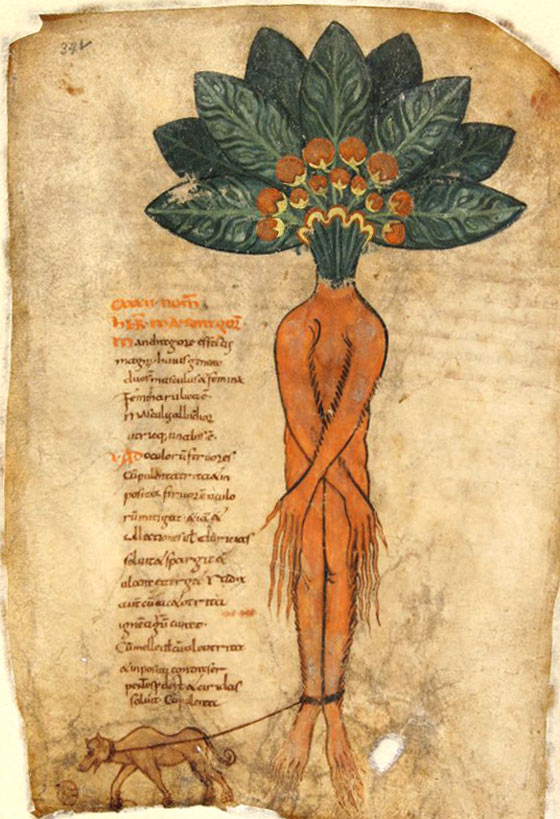

The idea the Hand of Glory could shed light might have arisen from nothing more than a misunderstanding of an ancient book. A great deal of superstition surrounded the mandrake plant – whose roots resemble a human body – and mandrakes found growing under gallows were particularly prized. ‘Hand of Glory’ is probably a translation of the French Main de Glorie, which is believed to be a corruption of mandragore, meaning mandrake. According to the 4th-century author of an influential book of herbal medicine, Pseudo-Apuleius, the mandrake – among its other startling attributes – can ‘shineth by night altogether like a lamp’.

Pseudo-Apuleius’s Herbal was, until the 12th century, Europe’s most popular book on healing plants and copies of it were found across the continent well into modern times. The capacity for illumination the Herbal credits the mandrake with and its confusion with the term Main de Glorie could – at least in part – account for the legends of the Hand of Glory’s light-giving prowess.

The mandrake in Pseudo-Apuleius’s ‘Herbal’ – dogs were often used to uproot this magical plant.

The Lack of the Church’s Blessing and the Misuse of Holy ‘Magic’

Executed convicts were often denied a Christian burial and the lack of this sacrament may have given the Hand of Glory a devilish potency in the minds of the superstitious. Such notions can also be seen with the gruesome custom of making thieves’ lights from the bodies of unbaptised children.

These dismal objects were often imbued with the magic conferred by an execution – it was considered best if the infant’s toes or fingers came from the womb of an executed felon. But folklore also ascribed a strange power to the fact the children hadn’t undergone baptism. It may have been believed that – as the purifying holy water hadn’t been sprinkled upon them – the babies’ relics were empowered with a demonic force.

The idea unbaptised children were ‘unhallowed’ was once widespread, with the baptism ritual not only marking the baby’s entrance into the Church but also into the local Christian community. Stillborn or unbaptised children couldn’t be buried in consecrated ground. Instead, it was the duty of midwives to respectfully – but without ceremony – bury the bodies in some field or wood.

Medieval and early modern documents, however, feature complaints about midwives being less than conscientious about this responsibility. They sometimes carelessly left the tiny corpses where pigs or wild animals might find them or even abandoned them on dunghills. All this underlines how necessary people felt baptism was for a person to be considered fully human. The fact thieves’ lights came from bodies that had received neither baptism nor Christian burial likely boosted the faith of the credulous in their potency.

But, while the absence of the Church’s blessing seems to have aided the effectiveness of the Hand of Glory and thieves’ lights, the Church’s otherworldly powers – even if harnessed dishonestly – could, paradoxically, make such items more formidable. The Whitby Hand of Glory had to hang for a night in a church porch while the sorceress in the Netherlands made sure six masses were said over her gruesome finger.

Common Elements from Folk Magic and Folktales

In addition to the potent mixture of all the above, the traditions around the Hand of Glory seem to have combined the sort of practices – doing things at midnight, journeying to crossroads, utilising black cats – that are common in folk magic across the world.

As for the reputed adventures involving the Hand of Glory, these stories contain elements frequently found in folktales. It’s interesting that it’s usually a person of humble status who foils the thieves. Normally, it’s the maid, but in the German story above it’s a beggar and, in one account from England, a cook disables the Hand of Glory with a conveniently placed milk jug. In folktales, those of modest rank – children, servants, peasants, vagrants, even animals – can demonstrate a resourcefulness and cunning that eludes the better-educated, powerful and wealthy. The heroes and heroines of folktales are also – like the maids – often young.

The accounts of the Hand of Glory contain an element of rough justice, another common facet of folk stories. Those using ghastly body parts for criminal purposes are thwarted, arrested, wounded, impoverished, imprisoned or hung. Though Hands of Glory really existed, the narratives of encounters with them do appear to have borrowed from the usual range of folk archetypes and motifs.

But does the Hand of Glory belong in a more credulous, folkloric past or does the malignant light of its flaming fingers still cast its shadow over literary culture and the modern epoch? Let’s find out in the next section.

The Flickering Hand of Glory Casts Its Shadow over Literature, Culture and the Modern Age

The Hand of Glory inflamed the gothic creativity of some members of the Romantic movement. Robert Southey has the hand crop up in his Thalaba the Destroyer (1801):

‘A murderer on the stake had died;

I drove the vulture from his limbs, and lopt

The hand that did the murder, and drew up

The tendon strings to close its grasp;

And in the sun and wind,

Parch’d it, nine weeks exposed …

Look! It burns clear, but with the air around,

Its dead ingredients mingle deathliness.’

Writing under his pseudonym of Thomas Ingoldsby, Richard Barham included a Hand of Glory in The Ingoldsby Legends (1837):

‘Open, lock,

To the Dead Man’s knock!

Fly bolt, and bar, and band!

Nor move, nor swerve,

Joint, muscle or nerve

At the spell of the Dead Man’s hand!

Sleep all who sleep! – Wake all who wake!

But be as the dead for the Dead Man’s sake!’

Though few – as far as I know – would nowadays use the Hand of Glory as an aid to theft, its doleful light still, in a strange way, illumines modern culture. The Hand of Glory has made quite a few appearances in books, films, TV programmes and video games.

The Hand of Glory features in the novels Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (in which Draco Malfoy stumbles across a hand in a ‘dark arts shop’) and Harry Potter and the Half-blood Prince. The hand also made it into the film version of Chamber of Secrets. All this has no doubt brought the Hand of Glory – through J.K. Rowling’s outpourings – to millions of page-flickers and cinemagoers.

A Hand of Glory appears in the dark Hollywood film Angel Heart (1987) as well as in the Amicus horror production – starring Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee – The Skull (1965). The hand has turned up in Buffy the Vampire Slayer and in Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere, where a Hand of Glory is discovered in a floating market. Perhaps most famously, a Hand of Glory features in the classic 1973 folk-horror film The Wicker Man. Here a pagan landlord uses the hand to lull the Christian policeman Sergeant Howie to sleep, despite the landlord’s daughter fearing the hand’s potency could mean ‘he might sleep for days.’

The Hand of Glory makes an appearance in the 1973 folk-horror classic ‘The Wicker Man’.

Maybe we’ll never quite escape the grisly, bizarrely compelling legend of the Hand of Glory. The hand may well be shedding its sinister light upon us for some time to come.

(This article’s main image is an illustration from the Little Albert, showing the two variations of the Hand of Glory.)

A hand of glory also appears in the John Bellairs novel “The House With A Clock In Its Walls”.