In the early 20th century, in the steel mills in and around Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, a strange folklore seems to have grown up – a folklore not of villages and forests and witches and ghosts, but of girders, clanking hammers, rail tracks and molten metal. Amongst immigrant steelworkers from Eastern and Central Europe, legends of a superhuman figure are said to have arisen – legends born of iron ore, moulded in furnaces and developed during days of backbreaking labour.

This figure was named Joe Magarac and – like those who told his stories – he was a steelworker. Like them, Joe was of immigrant status, but he hadn’t been born in the natural way. It’s claimed he miraculously emerged from either an iron ore mine or an entire mountain made of that rock. Some say this mystical birth occurred in America’s Allegheny Mountains, others that it happened back in the ‘old country’. Wherever it took place, Joe’s strong accent and broken English marked him as unmistakably of immigrant stock though his ethnicity was never certain – some say he was a Croat, some a Serb, others a Hungarian, Slovak or Pole. Some maintain Joe Magarac – a giant – sprang into the world fully formed, others that he spent his childhood and youth inside a furnace.

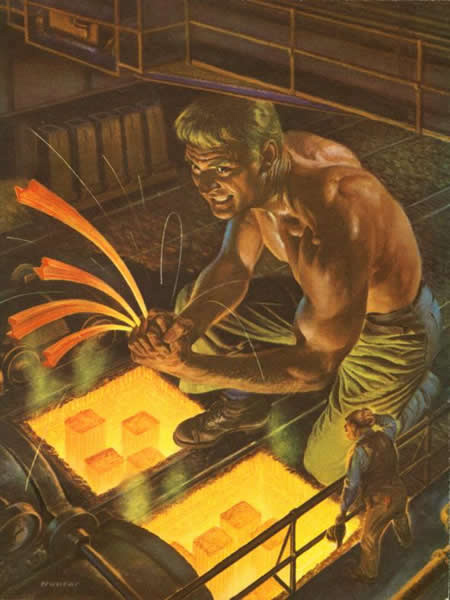

Joe wasn’t made of human bone and flesh, but entirely of steel. More modest accounts give him a height of seven feet, but in the most extravagant tales he was as tall as a smokestack. His back, it’s claimed, was as large as the steelworks door. His neck resembled a bull’s while his biceps were wider than a man’s waist. Joe Magarac used his hands – which were the size of buckets – as ladles to pore molten steel. Some even say metal was his food – that he ate ingots as other men ate meat and drank molten steel like soup, downing a gallon in just one swallow. Less outlandish stories have him consuming normal food, but carrying his sandwiches in a washtub rather than lunchbox.

Joe’s gargantuan stature and inhuman flesh made him a tireless worker. He could toil for 24 hours and do the work of 29 men, needing just short breaks and never having to sleep. With his bare hands, he squeezed railroad spikes out of spheres of molten steel, stirred vats of bubbling metal, and twisted horseshoes and pretzels out of iron ingots. From cooling metal, he could sculpt cannonballs as easily as children make snowballs. When a vat of liquid steel was ready for pouring, he’d taste it to check it was just right like a chef might sample a spoonful of broth. Joe then blew the blisteringly hot steam from his nose like cigar smoke.

Despite his fearsome physical capabilities, Joe was good-hearted. He once took part in a weight-lifting contest, whose prize was the hand in marriage of Mary Mestrovich, the beautiful daughter of the boss of his work gang. Joe easily beat two other workers, Pete Pussick and Elli Stanowski, and a fellow from the next town. Finding out, however, that Mary and Pete were in love – and seeing the looks of adoration they shared – Joe stepped aside and let the couple marry. Besides, Joe didn’t want the distractions from work a wife would bring and knew any wife he took would get lonely as he laboured through his 24-hour days.

Mural of Joe Magarac, the legendary steelworker, in the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

Joe did much to help other steelworkers and save them from accidents. The more sensationalist stories claim he could be anywhere in the mill in seconds, sometimes hopping between the rims of boiling furnaces to get across the factory. On one occasion, a crane was transporting a ladle – brimming with 50 tons of molten steel – high above the busy shop floor. A crack appeared in the container and quickly spread, threatening that a ‘torrent of steel, bright as liquid sunlight’ might plummet onto the men below. Knowing that ‘another second and the whole heat would have poured down upon them’, the workers were surprised when ‘one among them – whom no one could remember having seen before – appeared to assume the proportions of a giant. Torso, shoulders, head, arms were magnified enormously and thrust upwards upon shaft-like legs to tower above the 50-ton ladle as if it had been a saucepan. The giant grasped the great lips of the crack, and ground them together so at once the ladle was made whole again. Not a flash remained visible, not a spark of fluid steel overflowed.’ The men were delighted at their escape, but were then shocked to see that ‘the ladle was being moved along in normal fashion. There was no giant anywhere … Were they awake? Did they dream?’

In another incident, a train loaded with ingots broke loose and thundered down a slope towards some workers. Joe sprinted into view and – catching hold of train’s last car – pulled it back up the hill. On a different occasion, a barge full of workers on a river swollen with floodwater was hurtling towards the pier of a bridge. The workers spotted a large form swimming in the engorged river – a gigantic hand thrust up, grasped the barge’s prow and guided it to safety. Joe Magarac was also credited with protecting an office from a run-away cart of pig iron and saving a boy struck with vertigo, who – teetering on top of a ladder – was about to plunge into a furnace. After rescuing the youth, Joe – apparently – disappeared into vapour: ‘the whistle blew about that time … and … several of the men noticed … the steam rising from the whistle was very dense that day and seemed to remain longer in the air than usual.’

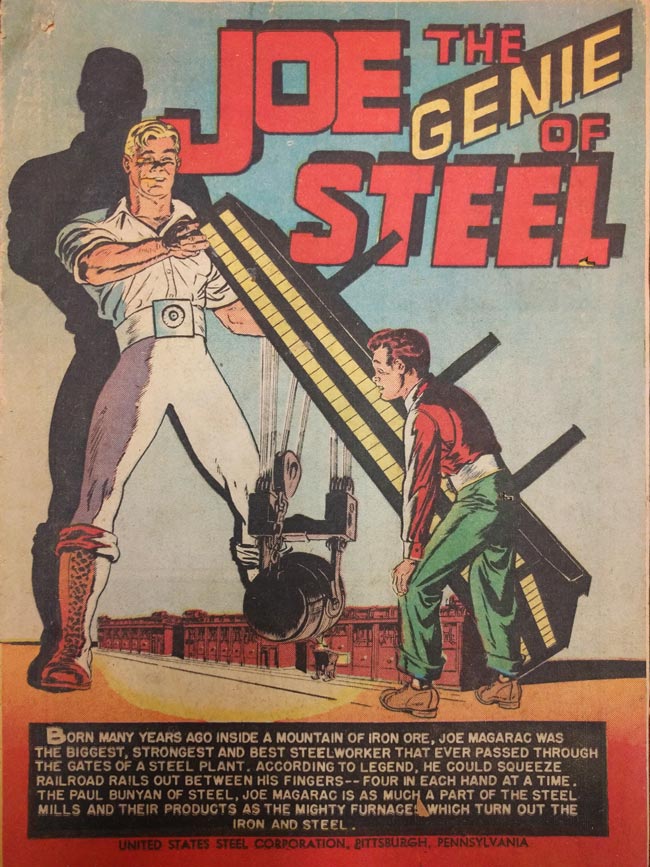

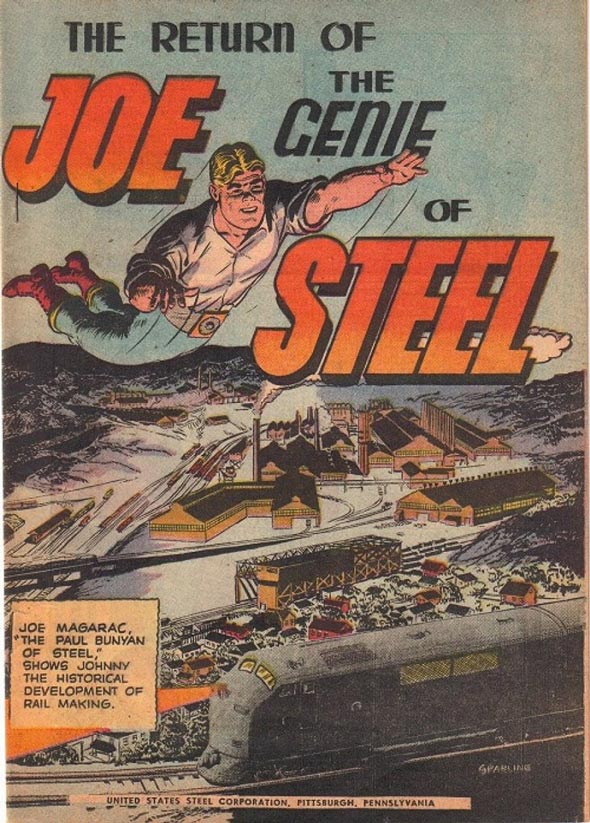

A particularly giant Joe Magarac in the US Steel comic Joe the Genie of Steel (1950)

The more exaggerated accounts of Joe Magarac do appear to see him as some sort of shapeshifter, almost a demi-god. One tale claimed he ‘was born of the mists that hover over the lakes and mountains of the “old country” and of the coal and iron of America. He is thus endowed with the strength of the earth but also with the elusiveness of the air. He is as large as the occasion demands but as fleeting as mist in the sun. He moves with the speed of light, rather, he seems to occupy whatever space he chooses without moving from spot to spot. He is at times the immovable body and at times the irresistible force. He appears in the midst of workmen taxed beyond their powers and with an effortless push or lift overcomes their difficulties; only, when they look around to see who has helped them, Joe Magarac is nowhere to be found.’

Joe was indeed known to assist when shifts had fallen behind, labouring alongside workers to help them catch up. Some say he did this to save his colleagues’ jobs, others that it was a patriotic act to keep steel flowing during wars. Once, to meet a staggering surge of demand, Joe put in a yearlong shift, working 365 straight 24-hour days. Some tales, though, do show Joe as somewhat more human. In his scant spare time, he was said to enjoy polka dancing and eating halushki (fried cabbage with egg noodles).

Like most tales of heroes, the legends of Joe Magarac usually end with Joe’s death. Most have Joe’s work rate being so incredible that his steelworks and nearby mills have to close for a few days due to overproduction. After this enforced time off, Joe’s fellow workers – or his boss in some versions – return to find Joe, unable to stand the idleness, melting himself down in a Bessemer furnace. Respecting his wishes, they let him sink into the molten metal and the steel produced from Joe’s body is the best ever made. Some say it was used to build a new mill, meaning even more steel could be churned out and more workers given jobs. But, as with many mythological heroes, there are those who refuse to accept Joe has truly died. Some assert he lives on in the girders created from his body, with his spirit infused into the buildings and bridges they helped construct. Others maintain he didn’t die at all and that he’s living in an abandoned steel mill waiting for production to restart.

But where did the legends of Joe Magarac come from? Were they really born out of the everyday experiences of steelworkers or were they helped into existence by the midwifery of professional writers? Is there any flavour of the ‘old country’ in the legends, are they rather based on ‘grand universal myths’ or might they be pieces of ‘genuine’ American folklore? Or are they just ‘fakelore’ with roots no deeper than the imaginations of short story authors, comic book creators and advertising executives? And how does Joe compare to other superhuman American worker-heroes like the lumberjack Paul Bunyan, the cowboy Pecos Bill, the sailor Old Stormalong and the tunneller John Henry?

What did Pittsburgh’s steelworkers really think of Joe Magarac? Was he seen as a saviour and hero or as a gullible idiot or even traitor to the working class? Was he an object of ridicule, of admiration or of sympathy? Was he an emblem of the nobility of labour or a personification of the alienation, overwork, xenophobia, exploitation, unrealistic demands and dangers of accidents and even death that immigrant steelworkers regularly faced? Was he a figure celebrated by the capitalist right or socialist left? Was he perhaps all these things and less and more? And does Joe still have relevance in a post-industrial epoch or is his legacy rusting away like the skeleton of an abandoned factory?

Read on for tales of naïve failed scriptwriters, of invisible donkeys’ ears, of the lassoing of tornadoes, of corrupt politicians and anti-immigrant tirades sparking rampages through Washington, of metal men in Serbian folktales, of garish amusement park sculptures, and of strikers and private armies engaging in gunboat battles on America’s waterways.

A Failed Scriptwriter Commits the Outlandish Tales of Joe Magarac to Print

The earliest trace of Joe Magarac, at least in print, comes from a November 1931 article in Scribner’s magazine – The Saga of Joe Magarac, Steelman – by one Owen Francis. Somewhere between a journalistic write-up and short story, Francis’s article first introduces the legend of Joe Magarac then narrates Joe’s life and adventures in Francis’s approximation of a ‘Hunkie’ accent. ‘Hunkie’ was a slightly derogatory term for Eastern and Central European migrants, a term which could encompass Hungarians, Serbs, Croats and Slovaks. (The name probably derives from the fact these distinct ethnicities once lived in the Kingdom of Hungary, a semi-autonomous part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire).

Owen Francis had been an aspiring screenwriter and author of short stories. He began his working life in the steel mills of the Pittsburgh area before fighting in World War I. After recovering from exposure to poison gas, he attended the University of California then tried to make it in Hollywood. His Hollywood efforts, however, led to disappointment and he moved back to Pennsylvania, once more taking a job in the steel industry. He supervised groups of ‘Hunkies’ and – disgruntled by his lack of Hollywood success and disillusioned with the film world’s faux sophistication – found himself taking an interest in these marginalised immigrants. His attitude towards them was both affectionate and patronising. The Hunkie, Francis felt, instinctively ‘understood life’ and was ‘the best worker within our shores’. In addition to ‘working for a considerable number of years with a Hunkie on my either side’, Francis claimed to have eaten with them and spent ‘many evenings in their homes’. During these times, Francis asserts, he heard lots of curious stories about a ‘Mr Joe Magarac’.

Francis’s fascination with such matters began when he ‘often heard many of the Slavs who worked in the mills call one of his fellow workers magarac’. Aware that ‘literally translated the word magarac meant jackass’, Francis ‘questioned my Hunkie leverman as to its meaning as understood by Hunkie workers. He gave me a vivid explanation.’

A magarac was, apparently, a labourer who – donkey-like – was content to do nothing but work hard and eat: ‘Magarac! Dat is man who is joost lak jackass donkey. Dat is mans what joost lak eatit and workit, dats all.’

To illustrate his point, the leverman jabbed his finger ‘towards another of his race, a huge Hunkie by the name of Mike’ and yelled, ‘Hay! Magarac!’ Immediately, ‘Mike’s thumbs went to his ears, and with palms outspread his hands waved back and forth while he brayed lustily in the best imitation of a donkey he could give.’

‘See,’ my leverman said, ‘dere is magarac. Dat is Joe Magarac for sure.’

The leverman and Mike then ‘both laughed and spoke in their mother tongue, which I did not understand.’ You might think that to be called a donkey is an insult, but Owen Francis believed ‘from the tone of voice and the manner in which it was used, that it was seldom used derisively.’

According to Francis, the mythical figure of Joe Magarac was ‘a man living only in the imagination of the Hunkie steel mill worker. He is to the Hunkie what Paul Bunyan is to the woodsman and Old Stormalong is to the men of the sea. With his active imagination and childlike delight in tales of greatness, the Hunkie has created stories with Joe Magarac as the hero that may in the future become the folklore of our country … (Magarac) belongs to the mills as do the furnaces and the rollers.’ Francis argued that the Hunkie ‘has created a character and woven about him a legend which admirably fits the environment in which he, the Hunkie, has been placed. Basically, the stories of Joe Magarac are as much a part of the American scene as steel itself.’

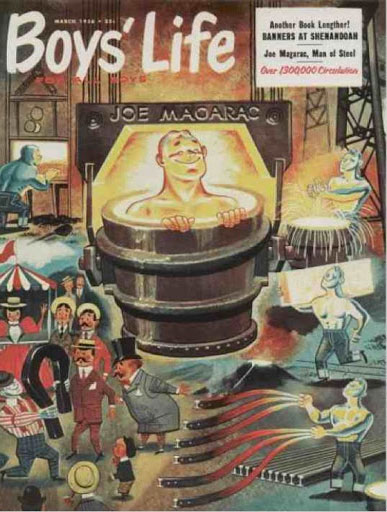

A rather blissful-looking Joe Magarac melts himself down on the front of Boys’ Life – the monthly magazine of the Boy Scouts of America

In Francis’s narration of the Joe Magarac legend, Joe first appears during the weight-lifting contest for the hand of Mary Mestrovich. He easily picks up the heaviest bar – which no one else can lift even an inch off the ground – and ties it into a knot. After being asked in amazement what kind of man he is, Joe pulls off his shirt to show that ‘all over he was steel … steel hands, steel body, steel everything.’ Joe declares, ‘Me, I was born inside ore mountain many years ago. To-day, I comit down from mountain in ore train and was over in ore pile by blast furnace.’

Joe moves into Mrs Horkey’s guest house, telling his landlady, ‘I no wanit room, joost five big meals a day, dats all, for I workit night turn and day turn all at the same time.’ Joe gets a job in the mill, where ‘he go sit in furnace door, with fires from furnace licking round chin’. He stirs the steel with his hands ‘while she was cookit’, scoops up big handfuls of molten metal which he dumps into moulds, and ‘he makit rails. Eight rails at a time, four by each hands … squeeze ’em out from fingers.’ The mill soon has to suspend work due to this overproduction so Joe sits in a ladle of molten steel and melts himself down. He’s then rolled out, chopped up and – having turned himself into the ‘best steel what was ever made’ – he’s used to construct ‘the best mills for sure … dat is why when somebody call Hunkie magarac he only laughit and feel proud as anything.’

Francis wrote, ‘The saga of Joe Magarac is more typical of the Hunkie than any tale or description I might write. It shows his sense of humour, his ambitions, his love of his work: a good-natured, peace- and home-loving worker.’

Owen Francis’s tale of Joe Magarac proved popular, but – as Magarac had supposedly sprung out of the organic folklore of migrant steelworkers – Francis couldn’t claim ownership of the character and other creatives soon embellished the Magarac myth. Over the next twenty or so years, Joe Magarac would appear in short stories, comics, poems, novels, paintings, murals, songs and advertisements. He’d become as much a part of the mythic American landscape as Pecos Bill – the gigantic cowboy said to have created the Gulf of Mexico by lassoing a storm cloud – and Paul Bunyan, a superhuman lumberjack who formed 10,000 Minnesota lakes with his footprints.

Joe Magarac plays pat-a-cake with white hot steel in a Shell Oil ad from 1953

Francis stressed the Americanness of Joe Magarac, stating, ‘Although the stories of Joe Magarac are sagas, they have no tangible connection, so far as I have been able to find, with the folklore of any of the countries which sent the Hunkies to these United States.’ But is this entirely true or might the Joe Magarac legends indeed reflect tales brought over from Europe or patterns of myth widely known to humankind? Or, to go to the other extreme, might – rather than having deep roots in Europe’s soil or in the bedrock of the collective consciousness – the stories of Joe Magarac have roots that don’t penetrate further than the minds of over-excitable writers and even corporate or political propagandists? Let’s find out below.

Miraculous Births, Sacrificial Deaths, Metal Men and Frogs – Might Joe Magarac Derive from European Folktales and Universal Hero Myths?

It could perhaps be argued that Joe Magarac’s unusual birth, heroic deeds and untimely sacrificial death follow common patterns of hero myths, encapsulated in ideas put forward by thinkers such as Joseph Campbell, Otto Rank, Lord Raglan and David Adams Leeming. The hero is often not conceived or born in the normal way, perhaps – for instance – being sired by a god on a mortal woman. Little is then known about his childhood and youth, but as an adult – often as a young man – he performs miraculous actions and incredible feats. The hero’s death is also often unusual – he might die while still quite young and the death might be voluntary and sacrificial. But many think such a demise is not a real death or at least not final. The hero may not have a tomb or the tomb could turn out to be empty. He might resurrect himself, ascend from the underworld or somehow live on, perhaps planning to return one day to help his people.

An example of such a hero would be Jesus Christ. Christ was born of a virgin, his birth was marked by strange signs, and information is scant concerning his childhood and youth. After several years of teaching and performing miracles, he died, voluntarily on the cross, as a sacrifice for others, but then overcame death via the Resurrection, leaving his tomb vacant. King Arthur too came into the world in an unconventional manner, conceived thanks to Merlin’s trickery. It’s said Arthur lies in slumber rather than death and that he’ll come back when England really needs him. Several Greek demi-gods were conceived by deities on mortal woman, enjoyed immense strength and superhuman powers, and managed to visit the underworld and ascend out of it again. Might Joe Magarac – with his miraculous birth, his childhood hidden away in a furnace, his acts of superhuman strength, his voluntary and sacrificial death, his living on in the steel he created and his promise to reappear one day – fit at least some of these common patterns?

A hero winning a maid’s hand in marriage via some test of strength or skill is also a widespread folklore motif. In order to marry Princess Iole, Heracles was obliged to beat the king’s sons in an archery contest. In the Welsh collection of myth the Mabinogion, the hero Culhwch has to complete 40 impossible-sounding tasks before he can wed a giant’s daughter. Tales of marriages celebrated after such trails can be found in the areas the Hunkies originated from. Several stories in the collection gathered by the Serbian linguist and curator of folksongs and folktales Vuk Karadzic (1787-1864) have a marriage-seeking hero outwitting a girl’s father or even the girl herself.

In Joe Magarac’s weight-lifting competition, though, rather than claiming the beautiful maiden, Joe steps aside and lets her marry someone else. There are, however, folktales in which this happens, including one of Karadzic’s called The King and the Shepherd. After a shepherd defeats a king in a contest of cleverness, he demands his bride and as ‘the king saw no way out of the situation … he gave the girl to the shepherd.’ The shepherd then surprises everyone by surrendering the maiden ‘to the rich man, who in exchange rewarded him with immeasurable treasure.’

Another of Karadzic’s tales that may have some vague influence on the Joe Magarac legends is The Man of Iron. The tale’s hero – the youngest son of a king – is saddled with the misfortune of being married to a frog. This amphibian later turns out to be a beautiful woman, which makes his mother the queen jealous. In revenge, the queen persuades the king to give her son arduous tasks. These the prince accomplishes with the help of his brother-in-law, who – still presumably in frog form – lives in a nearby well. After overcoming two tricky challenges, the prince is summoned to his father, who says, ‘I hear you brag about being able to bring the iron man.’ The young man protests that he’s never made such claims, but the king vows that if his son doesn’t present him with this fearsome being, he’ll forfeit his head. The prince’s wife urges him to go to the well and beg his brother-in-law’s aid. The brother-in-law merely answers, ‘I’ll be up in a moment, but don’t be scared or petrified.’

Suddenly the prince sees the iron man right in front of him and ‘Oh, he was tall and frightening.’ The iron man heads to the king’s castle, dragging a mace ‘with which he ploughed the land, leaving a trail behind as if eight strong oxen had ploughed instead.’ Seeing the iron man approaching, the king rushes into the fortress, bolting all the doors and fleeing to the top of the tallest tower. The iron man, however, opens each door with one punch. Reaching the tower-top chamber, he demands to know why the king has sent for him but the monarch is too terrified to speak. The iron man punches the king on the forehead, the king falls down dead and the iron man – who turns out to be the prince’s frog brother-in-law – places the prince and his wife on the throne. The two reign happily for the rest of their lives.

Another aspect of European folklore that bears similarities to tales of outlandish American heroes like Joe Magarac, Paul Bunyan and Pecos Bill is the folklore of giants. Giants are often credited with establishing unusual landscape features. In Cornwall, for instance, the large boulders that scatter Mounts Bay are said to have been left after a fight between two giants and the shingle spit Loe Bar – which separates the freshwater Loe Pool from the ocean – is reputed to have been formed from a bag of sand the demonic giant Jan Tregeagle dropped while wading across an estuary. In addition to creating the Gulf of Mexico, Pecos Bill is said to have carved out the Rio Grande with a stick. It’s claimed Paul Bunyan created the Grand Canyon by pulling his axe behind him and the volcano Mount Hood by putting stones on his campfire.

While there’s no direct evidence connecting Joe Magarac with specific European folktales, it’s likely that the ‘Hunkie’ immigrants would have had at least some knowledge of the folklore of their regions. It’s not beyond the frontiers of probability that folktales and ‘universal myths’ may have at least given them elements out of which new stories could be conjured to suit a very different environment to the one they’d grown up in.

That’s one possibility, but there’s also the possibility that the accounts of Joe Magarac are what’s known as ‘fakelore’. Owen Francis may have distorted and embellished the Hunkies’ tales so much they lost all serious claims to be genuine legends, Francis may have made the stories up entirely, or the Hunkies themselves might have simply invented them to please or fool him.

Was Joe Magarac a Creation of ‘Fakelore’?

‘Fakelore’ may be defined as manufactured or otherwise artificial folklore masquerading as authentic tradition. The term ‘fakelore’ was created in 1950 by the American folklorist Richard M. Dorson (1916-81). Fakelore can refer to both stories that are completely invented and to folklore which is massively rewritten or reworked to appeal to contemporary tastes. With a purist zeal, Dorson spoke of a ‘battle against fakelore’ and soon had some of America’s favourite heroes in his sights.

One of the best-known characters savaged by Dorson’s pen was the cowboy Pecos Bill. Tales of Pecos Bill entered popular American culture thanks to short stories written by Edward S. O’Reilly. O’Reilly’s stories were first published in 1917 in The Century Magazine then reprinted in a book in 1923 called the Saga of Pecos Bill. O’Reilly had claimed his tales were based on the oral legends of cowboys who’d ventured west to settle Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. Dorson, however, asserted that O’Reilly had simply made Pecos Bill up and that later writers had then added to and embellished the giant cowboy’s escapades. (Motifs from myths and folktales do, however, have a habit of finding their way into works of art and literature as well as cropping up in ‘genuine’ folklore.)

Pecos Bill, the cowboy hero of American ‘fakelore’, lassos a tornado – a feat which led to the formation of the Gulf of Mexico. (Photo: Maroonbeard)

Dorson took on another American icon – the lumberjack Paul Bunyan. Unlike Pecos Bill, there’s evidence Paul Bunyan started life in stories lumberjacks told in the Great Lakes region and it’s been suggested these stories may be ultimately based on Bon Jean, a character in French-Canadian folklore. Still, Dorson regarded Paul Bunyan as a ‘pseudo-folk hero of 2oth-century mass culture’, arguing that popular perceptions of Bunyan bore little resemblance to the original folkloric figure. Tales of Bunyan became widely known thanks to a number of stories by William B. Laughead (1882-1958), an ad writer working for the Red River Lumber Company. These stories were published in a promotional pamphlet the company put out in 1916.

Dorson complained that the popularisers of folklore tended to turn it into something stereotypical and quaint whereas the authentic stories were often ‘repetitive, clumsy, meaningless and obscene’. The original Paul Bunyan tales had been full of logging jargon, which would make them hard for anyone not working in the industry to understand. Bunyan had been shrewd and sometimes downright dishonest, in one story tricking his men out of their wages. Dorson claimed the version of Bunyan found in mass culture had been sanitised with a ‘spirit of gargantuan whimsy (that) reflects no actual mood of lumberjacks.’ The poet and essayist Daniel G. Hoffman added that the Bunyan legends had become tools of capitalists, stating, ‘This is an example of the way in which a traditional symbol has been used to manipulate the minds of people who had nothing to do with its creation.’ Laughead may have been responsible for increasing Bunyan’s proportions from exceptionally tall and strong but still human-like to those of a being who towered over trees and casually created landmarks. He also seems to have endowed Bunyan with a pet blue ox named Babe, which nowadays the cartoonish Bunyan is rarely depicted without.

Paul Bunyan – the lumberjack hero of American ‘fakelore’ – with his blue ox Babe, in Bemidji, Minnesota. Numerous oversized statues of Bunyan can be seen across North America. (Photo: Today)

Another colourful American character accused of being sculpted by fakelore is the gigantic sea captain Old Stormalong. Though legends of Old Stormalong have been traced to African American folksongs from the 1830s and 1840s, the more outlandish tales about him – such as his ship being so big its masts nearly reached the moon – may have originated in books and pamphlets published in the 1930s. Other ‘fakelore’ characters include the Swedish American plainsman and cloudbuster Febold Feboldson – possibly created by a lumber salesman in the 1920s in Gothenburg, Nebraska – and Annie Christmas, a super-strong, African American keelboat captain.

So might Joe Magarac be fakelore, created solely – or mainly – by the pen of Owen Francis? In 1953, Hyman Richman of the New York Folklore Quarterly interviewed Slovakian steelworkers and found that most of them had never heard of Joe Magarac. The writer Stephanie Misko – upon interviewing her Slovakian grandfather and uncles, who’d worked in steel mills in the 1930s – also drew a blank. In Joe’s defence, it might be said that he was likely to be a Croatian legend rather than a Slovakian one as magarac means donkey in the Croat and Serb languages and the surnames in the Joe Magarac stories are Croatian. Also, references to some sort of man of steel – though not specifically Joe Magarac – have apparently been found in newspapers dating back to the 1890s and in records of oral traditions stretching back to the same decade. There’s also Pittsburgh’s famous Manchester Bridge, a steel (of course) structure spanning the Allegheny River that opened in 1915 and was demolished in 1970. The bridge featured four sculptures of iconic American figures, one a steelworker said to be Joe Magarac. I haven’t been able to discover if this figure was originally intended to be Joe Magarac or if Joe’s name became attached to it later, though if the statue was always thought of as Joe it would date the legend to before Francis’s storytelling.

Pittsburgh’s Manchester Bridge featuring the steelworker Joe Magarac (left). The figure on the right is the legendary miner Jan Volkanik.

It might also be said that the whole notion of ‘fakelore’ has come under criticism in recent decades. Rather than believing in a ‘pure’ and ‘authentic’ folklore that has to be sought out, scholars have argued that art and media on the one hand and folklore on the other are continually influencing one another. This process, many assert, should be studied rather than attacked. Dorson recognised this influence, but saw it negatively, feeling the embellishments of writers and advertisers ‘hopelessly muddied’ the very lore that had inspired them. The anthropology professor Jon Olson, however, heard Bunyan stories growing up thanks to lumber industry advertising and said of them: ‘The point is that I was personally exposed to Paul Bunyan in the genre of a living oral tradition, not of lumberjacks (of who there are precious few remaining), but of the present people of the area.’ Fakelore, according to such a train of argument, does have the potential to morph into folklore again.

But let’s – for the moment – assume that the Joe Magarac legends weren’t completely concocted by Owen Francis but were neither a generations-old tradition among immigrant steel workers in and around Pittsburgh. Let’s assume that Francis really did hear stories about Joe Magarac from the ‘Hunkies’ he worked alongside, but that such tales were very recent creations, invented perhaps as a joke to trick the gullible American foreman or as a means of venting the workers’ frustrations. What might such stories then reveal about immigrant steelworkers and the conditions they laboured and lived under?

Did Joe Magarac Personify the Difficult, Dangerous and Degrading Conditions in Pittsburgh’s Steel Mills?

For more than a century, the Pittsburgh area was the epicentre of US steelmaking. The great steel magnate Andrew Carnegie established his massive steel conglomerate in the region and Pennsylvanian steel was used in iconic American structures like the Golden Gate Bridge and Empire State Building. But such structures were reared on the toil of hundreds of thousands of workers, including the ‘Hunkie’ immigrants who poured into Pittsburgh to meet the mills’ gargantuan appetite for low-skilled labour.

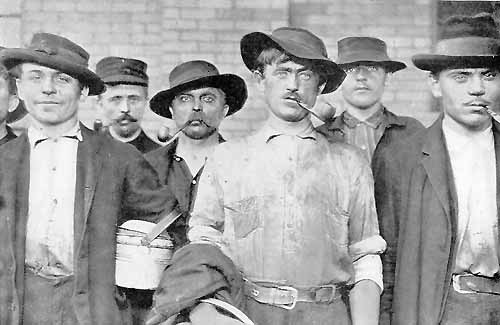

Life for the Hunkies was tough. They tended to be given dirtier, more monotonous and more dangerous work than American employees. They also faced worse treatment than immigrants from North Western European nations like Ireland, Britain, Holland, Germany and the Scandinavian countries, as migrants from these places were viewed as less ‘foreign’. The Hunkies laboured 12-hour days at just 15 cents an hour, significantly below the $3 a day that was considered a living wage at the time. The men often worked six or seven days a week and every fortnight there was a gruelling ‘swing shift’ – meaning they worked 24 straight hours due to the shifts swapping over. The work was hot and exhausting and accidents were frequent. One study showed that between July 1906 and June 1907 there were 195 work-related deaths in Pittsburgh and 526 in Allegheny County. The Hunkies’ scant time off was also far from comfortable. They tended to live in dingy lodging houses in poor, polluted and dangerous neighbourhoods and – if they had children – their families might be crammed into just a small room. Prospects of promotion were few, as advancement tended to be offered to American-born workers and migrants from less ‘exotic’ countries.

Immigrant steelworkers in the Pittsburgh area after finishing work

It’s easy to see how the figure of Joe Magarac might have emerged from such a situation. Joe is, however, unlikely to have been viewed as a hero by the workers who created him. He appears more to have been born out of bitterness, black humour, self-pity and sarcasm and to have been an ironic statement on their lives. Joe – like them – puts in long, often 24-hour shifts. His death by melting in the furnace or ladle could represent both the frequency of accidents and the idea that the workers were forced – metaphorically and sometimes literally – to sacrifice their lives to the mills. Indeed, Joe’s end could well have been a satirical comment on the absurd levels of dedication bosses expected. As for the weightlifting contest, Joe’s turning down of Mary’s hand could be making the point that the steelworkers barely had time for their families. Joe Magarac might also be a sardonic take on how the Hunkies felt others viewed them – as labouring beasts content with food, work and the poorest wages and living conditions. And – if they weren’t donkeys – they might just as well have been made of steel, fused with the very stuff they spent such long hours producing and the mills they manufactured it in.

There’s also Joe Magarac’s name. Francis seems to have been very wrong in his notion it was seldom meant as an insult. Richman found during his research that ‘the word magarac is rarely used without a sneer’ and Croatian dictionaries define a magarac as ‘an ignorant person’ or ‘one committing stupid acts and flippancies, a stupid unintelligent person, a foolish idiot … (and a) stubborn obstinate person.’ It’s difficult to imagine any hero in an English-speaking country going by the name of Joe Jackass.

Joe’s surname might also imply the mule-like strength and incredible stamina that – as the researcher Jack Santino found – some workers’ stories praise. The same tales can, however, caution workers against overdoing it or trying to work too quickly. Like Joe Magarac, such over-dedicated employees usually face a sad end. Another American worker-hero is the semi-mythical John Henry, an African American rail constructor who – during the building of a tunnel – engaged in a race against a new steel drilling machine using just his hand drill. Though John won, his efforts caused him to die of exhaustion. ‘Hammer songs’ – sung by labourers as they toiled – sometimes featured the legend of John Henry and warned against working too fast with lines like: ‘This old hammer killed John Henry, but it won’t kill me’. Men who violated the pace of the work by going too quickly tended to be shunned. Joe Magarac’s over-commitment to work is also mocked in his turning down of a beautiful wife in order to dedicate himself to his badly paid, unpleasant job and Joe even kills himself just because he has to stop working for a few days. It’s possible that – due to a process of linguistic and cultural misunderstanding – Owen Francis, with his sunny American outlook, didn’t comprehend his workers’ deadpan European humour and deep black sarcasm and totally misinterpreted the significance of magarac. A later story – Legend in Steel (1944) by George Carver – deals with Joe’s embarrassing last name by calling him ‘Magerac’. Carver also felt the need to comment that Joe’s surname ‘has no significance as far as I could learn.’ (The incidents of Joe saving other workers mentioned above are taken from Carver’s story and may, therefore, be later additions to the Magarac legend.)

Fears of overwork and unreasonable demands were perhaps understandable in an era influenced by approaches like Taylorism, Scientific Management and the Efficiency Movement. These schools of thought attempted to boost productivity by analysing the behaviour of workers down to the minutest detail. The management guru Frederick Taylor (1856-1915) – who began his career in the steel industry – would time workers with stop watches and observe the movements of their bodies in order to make sure the maximum effort and efficiency would be squeezed out of them. He also believed in selecting ‘first class men’ who had the motivation and energy for especially hard labour and paying them slightly more.

Taylor even came up with his own semi-mythical worker, a Dutchman named Schmidt, who he claimed he was able to get to carry 47 tons of pig iron a day instead of his previous 12 tons. Though Schmidt was based on a real worker, Taylor’s depictions of the Dutchman – as with the tales of Joe Magarac – seem to have been honed over the years. As Taylor’s influence spread, more Schmidts were selected in steelworks and factories, leading to resentment about the speed of work and maybe a little ethnic conflict as Hunkies were less likely to be singled out in this way. Perhaps the Croats and Serbs couldn’t resist calling the Schmidts of their workplaces the (unintelligible to them) insult of magarac.

All this has led some left-leaning writers to see Joe Magarac as not so much a workers’ hero but an anti-hero – a personification of how employers want their workers to be. The folklorists Gilley and Burnett (1998) state that a ‘magarac (a jackass) is someone that workers find to be an irrational super-worker.’ Joe Magarac could be an example of how a figure extolling values that are actually in opposition to the true interests of a group can be pushed onto that same group as a hero. For Gilley and Burnett, Joe Magarac was ‘the summation of what Capital asked for in its workers and not the hero of the working population.’

But did the myth of Joe Magarac represent only pro-capitalist interests or could the legend also be weaponised by the pro-worker left? Let’s see in the next section.

Joe Magarac – Tool of Capitalist Domination or Symbol of Worker Resistance?

The bosses of corporate America certainly embraced the imagery of Joe Magarac. A large mural of Joe can be found in the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, which was founded by Andrew Carnegie as one of his philanthropic gestures. In 1950-1, US Steel (which absorbed Carnegie’s companies) even put out two comics based on Joe’s exploits: Joe, The Genie of Steel and The Return of Joe the Genie of Steel. In a particularly thrilling scene from one of these publications, Joe appears in an adolescent boy’s dream to reveal to him the wonders of – the historical development of rail making. Joe featured in a Shell Oil advert in 1953 and was the subject of public murals and statues around Pittsburgh. He also – along with other ‘fakelore’ characters like Pecos Bill and Paul Bunyan – appeared in schoolbooks. Such figures – as well as being a useful way for busy teachers to get their pupils interested in subjects like history – promoted a ruggedly individualistic, hard-working and self-sufficient version of the American mythos.

Joe Magarac appears in the US Steel comic The Return of Joe the Genie of Steel (1951)

It’s hard not to view such portrayals of Joe Magarac as the epitome of the corporations’ idealised worker. Joe could almost be seen as a fantasy of the bosses – a labourer happy with his lot whose only desire is to toil for the company and whose only complaint is that he doesn’t always get to work as hard as he would like. Joe could represent the upper classes dealing with their guilt – admiring the ‘hardworking poor’ while conveniently forgetting they often have no choice but to submit to backbreaking labour. Joe Magarac could be seen as propagating the false idea that the system benefits all those involved in it rather than benefitting some enormously while disadvantaging others. Joe’s suicide even helps tackle the recurring capitalist problem of overproduction versus slack market demand. This part of the legend, it could be argued, promotes the notion that workers shouldn’t complain if they suddenly find themselves surplus to requirements. Joe might even be viewed as a martyr who’s ultimately of more value to the corporation dead than when alive. Gilley and Burnett thought the US steel industry needed to promote an image of the ideal worker as content and uncomplaining to guarantee the sector’s economic security.

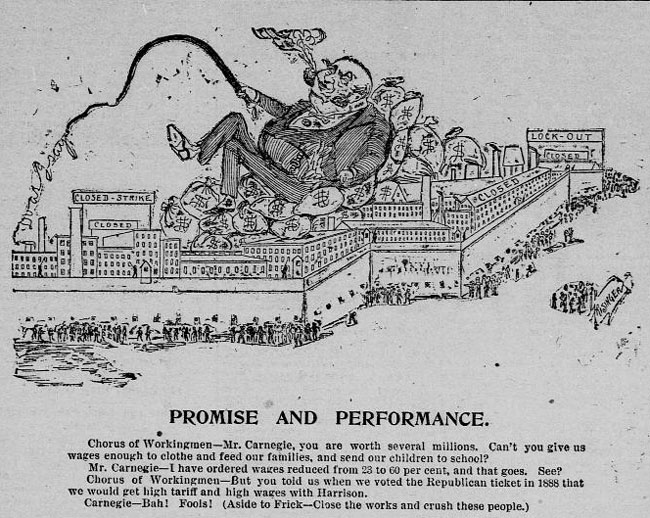

But there’s also evidence the myths of Joe Magarac could be turned around. There were apparently tales – perhaps union-instigated – of Joe participating in industrial disputes like the Homestead Rebellion of 1892 and the Great Steel Strike of 1919. The man of steel was said to have walked the picket lines, fighting strike breakers and Pinkerton thugs. The Homestead Rebellion – a dispute, in the town of Homestead near Pittsburgh, between the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers (AA) and the Carnegie Steel Company – was an especially dramatic conflict. Triggered by attempts to drop wages by 22% and break the power of the AA, the dispute saw workers locked out of plants, plants which were soon protected with high barbed-wire fences, sniper towers, searchlights and water cannons (some of which could spray boiling hot liquid).

The AA – along with another union, the Knights of Labour – soon called a strike. Determined to keep the mills closed, the unions patrolled the Monongahela River with a steam-powered launch and rowboats and organised men into military-style units. 24-hour picket lines were thrown up around the town and plant and strangers were questioned to make sure they weren’t strike breakers. The company, meanwhile, hired 300 security guards from the Pinkerton Agency, who attempted to access the plant via the river. After a brief gun battle on the Monongahela, the Pinkertons tried to land, leading to more shots being exchanged. The strikers attempted to sink the Pinkertons’ barges with a brass canon before hurling dynamite at their boats and even sending burning ships in their direction. This last action prompted some of the less experienced Pinkertons to plunge into the river to try to swim away. The Pinkertons surrendered and were captured, but the town was eventually taken by the Pennsylvania Militia. Strike breakers were brought in, production was restarted and the unions had to back down. For most of strike, however – at least until it had almost reached the point of collapse – the Eastern European workers were supportive participants. These were the same workers who writers like Owen Francis would characterise as passive ‘donkeys’.

A satirical cartoon depicting Andrew Carnegie, holding a whip and sitting on bags of money during the 1892 Homestead Rebellion

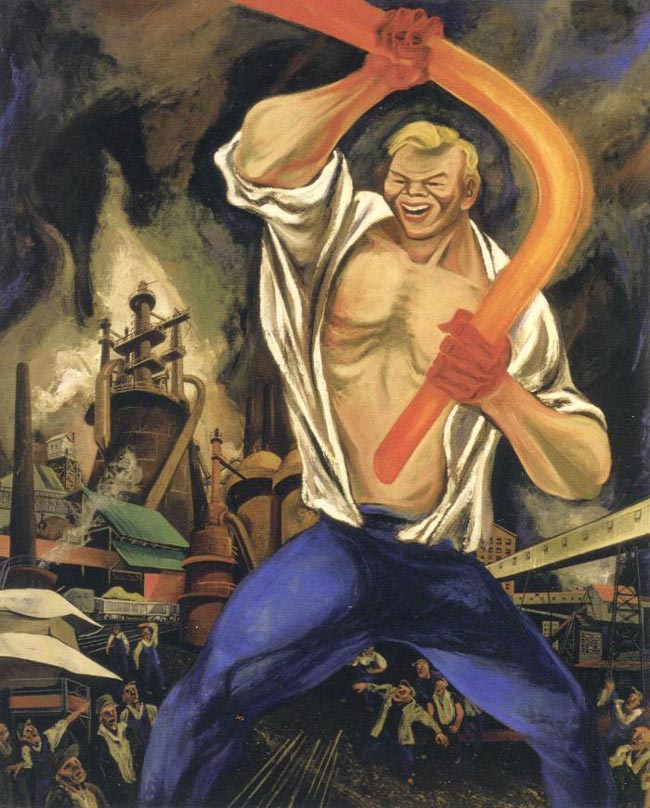

Writers and artists on the left weren’t afraid to use the persona of Joe Magarac to make political points. One of the most famous pictures of Joe – showing a laughing, blond-haired Magarac casually bending a red-hot bar of steel in front of a smoking industrial plant and crowd of amazed onlookers – was painted in 1946 by one William Gropper. Gropper had far-left sympathies, which were likely fuelled by the death of his aunt in an avoidable fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York in 1911, a tragedy in which 146 garment workers perished. In its description of the painting, New York’s Grey Art Gallery highlights how the ‘massive size’ of the steel mill is ‘diminished by Magarac’s hulking display of will’ and states that the picture ‘affirms in no uncertain terms the value of the working man’s spirit in post-war America.’

Joe Magarac (1946) by the left-wing artist William Gropper

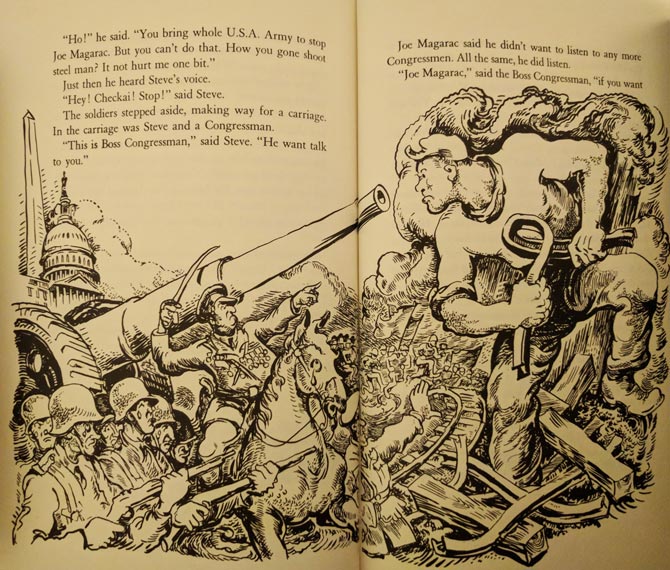

Another curious take on the Joe Magarac legend was the 1948 children’s novel Joe Magarac and his US Citizenship Papers by Irwin Shapiro. In Shapiro’s story, Magarac’s bosses realise his unusual birth in the iron ore mountain presents a bureaucratic obstacle to him acquiring American citizenship. A crooked manager tells him that this problem could be smoothed over if he slips a politician a $1,000 bribe so Joe works a marathon shift to earn the money. When the promised payment doesn’t appear, Joe melts himself down in a furnace and becomes a girder, which is used to reinforce the Capitol Building in Washington DC. In this form, Joe overhears congressmen making disparaging remarks about Hunkie immigrant workers as well as about migrants and workers in general. Magarac – furious at this bigotry – morphs back into a steel man and goes on a rampage across Washington. The removal of Joe’s girder means the Capitol soon crumbles. The army is called out, but even their guns and tanks can’t deal with the enraged steel giant. Joe’s only appeased when a delegation of politicians apologise for their slighting of working people and the president personally presents him with his citizenship papers. Restored to his amiable and easy-going self, Joe dances the Polka and returns to Pittsburgh to resume work in the mills.

A scene from the 1948 children’s novel Joe Magarac and his Citizenship Papers

Irwin Shapiro was a writer and translator who – with a Magarac-like work ethic – churned out over 80 books. Shapiro’s wife, Edna Richter, was involved in the American Federation of Government Employees union and Shapiro and Richter were, according to their son, ‘both deep in the Party’. (Meaning the Communist Party though both renounced any pro-Soviet sympathies after events like the Great Purge and Hitler-Stalin Pact). Shapiro’s brother-in-law worked for the United Auto Workers and was summoned before the government’s anti-communist House Un-American Activities Committee.

So Joe Magarac – like many symbols of folklore and, indeed, fakelore – was an ambiguous and malleable character who – like steel itself – could be bent, moulded and recast for a variety of purposes. The big man of steel could be used by very different people with very different aims. But what of Joe Magarac today? Is there any place for the metal giant in a Pittsburgh where the steel industry has largely vanished or has Joe Magarac melted himself down for the last time and quietly trickled away from the popular consciousness and folk memory?

Joe Magarac’s Legacy in a Pittsburgh Devoid of Steel Mills

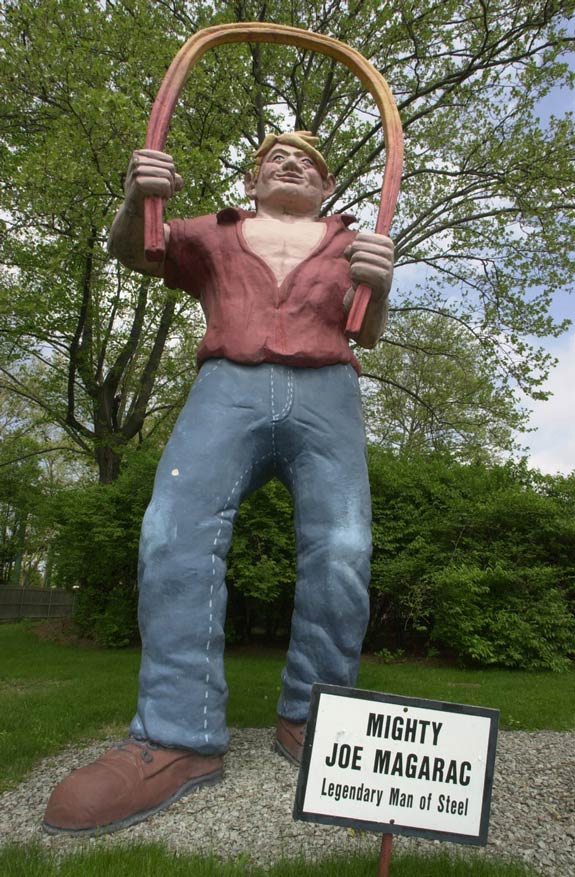

Due to deindustrialisation, there are no steel mills left now in Pittsburgh though a few small mills linger on in the surrounding area. How, though, has the city’s man of steel fared now the works so closely linked to his legend are no more? Joe Magarac is, perhaps surprisingly, still a common sight around Pittsburgh. The sculpture of Magarac from the old Manchester Bridge is preserved in a park on Pittsburgh’s North Side while another Magarac statue – bending a bar of steel – stands in Pittsburgh’s amusement park Kennywood Park. Over 30 murals of Joe Magarac are dotted around downtown Pittsburgh.

A giant Joe Magarac bends a bar of steel at Pittsburgh’s Kennywood Park amusement park.

Joe Magarac now seems to have lost any hint of his ‘donkey’ status and has become a symbol of a vanished industry and a reminder of the dignity of those who worked in it. He’s also an icon to cling to in the difficult times deindustrialisation has brought – times of low wages, insecure lower-skilled jobs and unemployment that often contrast unfavourably with the better wages and conditions the steelworkers eventually managed to win. Doris Dyen, from the Pittsburgh Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area, believes, ‘In the wrenching process of the steel industry’s precipitous declining, Joe Magarac has become immensely important to displaced workers, whose self-esteem and sense of identity have been severely challenged.’

Stephanie Misko feels that ‘Joe Magarac symbolises a century of multi-cultural explosion and labour exploitation obscured by the Pittsburgh fog … A city known for its emphasis on the preservation of heritage, Pittsburgh is claiming its Slavic “hero” as their symbol of a difficult but cherished past.’

Sculpture of the mythical steelworker Joe Magarac, saved from the now-demolished Manchester Bridge. It now stands in a Pittsburgh park. (Photo: Croatia.org)

The folklore – or fakelore – of industrial areas can throw up some strange beings. In Glasgow – another centre of the steel industry – an iron-toothed vampire was rumoured to live in the city’s Southern Necropolis and haunt the Gorbals neighbourhood preying on children. The odd figure of Joe Magarac seems to have arisen from a combination of Eastern European legends and ‘universal archetypes’; ironic reflections by migrants on the toil, struggles and stereotyping they faced; the outpourings of a gullible American foreman and frustrated scriptwriter; and the willingness of both corporate interests and political radicals to seize on the figure created. The giant conjured out of all this, Joe Magarac, is likely to haunt the American consciousness for some time.

(This article’s main image – showing Joe Magarac outside the Edgar Thompson Works, Braddock – is courtesy of darkinvestigations)

As a past steelworker in the Great Weirton Steel Plant, I really enjoyed your article on the lore of Joe.

Thanks Sean, so glad you enjoyed the tales of Joe Magarac