One of the oddest London ghost stories I’ve heard concerns Kensal Green Cemetery, a story that somehow combines the usual elements of gothic tombs and crooked headstones with a macabre love interest and even the emerging telecommunications technology of the day. This chilling account appeared in the book True Ghost Stories (1936), whose authors Marchioness Townsend and Maude Ffoukes swore that “the facts of the story were vouched for by the late Hon. Alec Carlisle, who told them to Maude M.C. Ffoulkes”. The date of this publication, as well as the telecommunications tech in the tale, would tempt to me to date it to the early decades of the 20th century. It involves a wealthy and fashionable publisher, who had risen from a humble background. The publisher’s ordeals after a visit to Kensal Green would forever alter his life in two significant ways.

Kensal Green Cemetery, an Abandoned Lover’s Tomb and the Spookiest Ever Telephone Mix-up

L. – as the man in the ghost story is referred to – was wandering through Kensal Green Cemetery after attending a funeral when he found himself lost in the sprawling 72-acre Victorian graveyard. Kensal Green was then one of London’s most fashionable burial grounds. The celebrities and innovators interred there included Charles Babbage, who had invented an early computer – called the Difference Engine – in collaboration with the daughter of Lord Byron. Other famous tenants were the engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel; the novelists Anthony Trollope, W.M. Thackery and Wilkie Collins; Pre-Raphaelite painter W.C. Waterhouse, and the news vendor W.H. Smith. L. drifted past the ivy-entangled angels and elaborate gothic mausoleums and strayed into a poorer and more overgrown section of the graveyard. Already a little depressed from the funeral, he began to experience a rising melancholy, a sense of oppression from all the monuments to death and mourning around him. He, however, attempted to shake such feelings off and to interest himself in the different tombs, in the grave markers and their inscriptions. What was life, after all, but for living and he was certainly living his. Moneyed and successful, he moved in the capital’s intellectual circles, enjoying a stimulating social life. He felt he still had much to enjoy in what he hoped would be a long and pleasurable existence.

Kensal Green Cemetery was the burial place for some of London’s wealthiest and most famous people (Photo: Marathon)

Still, the cold, foggy, drizzly weather saddened him; he was irritated by the insistence of the clay soil of the cemetery in clinging to his feet. He wandered down a leafy pathway, taking in the epitaphs on the graves when his eyes flicked over an inscription that made him suck in a breath. He peered more closely and shuddered as he realised he hadn’t been mistaken. The grave was hers, all right. The headstone belonged to an ex-lover, Elsie, who L. had long ago left behind as his personal and professional life took an upward turn. Elsie – a lowborn girl from a dreary suburb nicknamed “the Clerks’ Dormitory” – had possessed “no working brains and no money to speak of”.

The publisher felt a stab of guilt as he remembered his decision to ditch Elsie, feeling she would inevitably hamper his social rise. He recalled how – on hearing of her passing – he’d been too embarrassed even to send a wreath from his Bond Street florist to her humble address. L.’s guilt was deepened by her grave’s condition. A simple cross – soot and weather-stained – poked out of the naked earth, listing at an angle “as if tired”. L. imagined Elsie “lying alone in wet clay and deeper darkness – nasty, sticky clay like that which he tried to clean off his boots by rubbing them against the marble surrounds.” L. made a note of the grave number – perhaps he could pay for a more dignified memorial. After all, someone else might “stumble upon it who knew the story and the name of his invisible mistress.” He winced at the thought of the gossip her dilapidated resting place might arose.

Elsie’s grave was found in a more modest section of Kensal Green Cemetery (Photo: Mr Ignavy)

Swiftly finding his bearings, L. strode from the gates of Kensal Green Cemetery and got into his car. But as he was driven back to Mayfair, he could pay no attention to the copy of The Times that vibrated on his lap. Arriving home, L. gave his coat and hat to his valet – Bowden – and tried to settle down to dinner. Yet, throughout the meal – and throughout the evening – he found himself weighed down by thoughts of mortality and memories of his defunct sweetheart. His mind became so gloomy that – after dismissing Bowden and the other servants – he decided to telephone a friend, hoping this acquaintance could call round for an hour and cheer him up.

L. went to the phone in his library, dialled the operator and asked for what he thought was his friend’s number. But as the operator put him through, L. realised he had requested Kensal Green _____, the number of Elsie’s grave. He stammered out his error, but it was too late and cold shivers overtook him as the receiver at the other end was picked up. A familiar voice answered. At first it sounded muffled, but soon became clearer.

“Yes, who’s calling?”

L. was so shocked he couldn’t help but give his name.

The other speaker gasped with delight.

“Why, it’s never you, darling,” Elsie exclaimed. “Do you want me? Of course, I’ll come.” (This was the way Elsie had always spoken during their telephone calls.)

L. tried to stutter “No, no, no” but couldn’t get his lips to form the words.

“I won’t be long,” Elsie said. “But I was very far away, darling, when you rang up.”

In utter horror, L. let the receiver slip from his hand. He thought about fleeing the house, but – in his panic – couldn’t make up his mind so he ended up waiting to see what would occur. When would the ghost arrive? How would she look? Surely she wouldn’t be clad in “her earth-stained shroud, with the seal of corruption on her face?” L. poured a large brandy and tried to calm down. “Damn it all, he wasn’t afraid of any woman living, much less a dead one. Let her come – even if she brings all the clay of Kensal Green with her!”

The front door opened quietly then closed itself. The temperature plummeted and from the hallway came the sound of footsteps stumbling and dragging, as if their owner’s legs had been stiff for a long time. Next came three gentle knocks on the library door. L. did not get to greet his ghostly visitor. He passed out in a faint and was discovered by Bowden in the morning’s early hours.

“And believe me or believe me not,” Bowden said, “bits of wet clay were sticking to the carpet and some was on his dinner jacket. Beats me how it got there. As for the hall mat; it was all mussed up. Why can’t people wipe their feet like Christians?”

After some time, L. began to recover from his experience of Kensal Green Cemetery and its ghost. He started to enjoy his successful and luxurious life again. But the incident bestowed upon him two new habits he would always thereafter follow. He would never again use the phone or attend funerals.

What Does This Strange Ghost Story of Kensal Green Cemetery Tell Us?

Whether these outlandish events happened or not, they perhaps give us an insight into the mentality, concerns and upheavals of the period in which the tale is set. This ghost story, first of all, has a strong class element. There’s L.’s urge for social mobility and his eagerness to leave his embarrassing past – represented by Elsie – behind. But despite L.’s success and wealth, there’s a sense he’s not totally accepted in fashionable and privileged circles. L. “preferred to speak to titles” and “knew to a nicety the degrees of the social scale and what status is demanded by Claridge’s, the Ritz and the Berkeley.” However, “he collected few friends but numerous acquaintances” and “his name never featured as a guest at Bohemian or theatrical gatherings”. L. cannot escape his origins – they continue to haunt the publisher. One slip-up under stress has the ghosts of his past resurrected. A past he’d hoped was dead and buried disinters itself and relentlessly hunts him down.

There’s also, of course, the class consciousness of the authors – how they give their story more credibility by attributing it to the Hon. Alec Carlisle. Their book True Ghost Stories is full of such name drops of the powerful and influential. In the stories themselves, many of the characters sport titles or reside in manor houses and even some of the spooks boast immaculate dress sense. As for Marchioness Townsend – the term ‘marchioness’ denotes a noble rank, meaning a marquess’s wife or widow. The self-consciously bohemian Maude M.C. Ffoulkes was a literal ghost writer who sought to join that aristocratic set and who collaborated with down-at-heel, exiled European royals in the early 1900s to produce – sometimes scandalous – autobiographies.

A lavish tomb in London’s Kensal Green Cemetery (Photo: Marathon)

The story of Kensal Green Cemetery’s ghost also seems full of repressed sexuality. Though society had by that time shaken off some of the more rigid Victorian restrictions, many still had a horror of the body and sex, especially – it seems – the sensuality of the lower-class and female. The fact that Elsie’s desires are so strong they can resurrect her from the grave and are expressed in such gothic and lurid form, the fact that L. finds himself ravished and daubed with graveyard dirt perhaps hint at sexual feelings that many in society would have liked to have kept in a box buried under six feet of mud but which had the distressing habit of breaking free from their confinement.

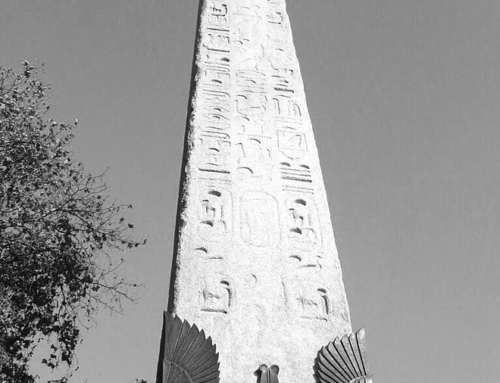

Another aspect of the tale is how the superstitious and folkloric combine with social progress and modern technology. There’s L.’s use of new-fangled telecommunications, but it is that very technology that delivers the ghost to his door. It seems the supernatural has the ability to subvert humanity’s most impressive inventions. Even the location – Kensal Green Cemetery – hints at social renewal. Kensal Green is one of the ‘Magnificent Seven’ – a series of spacious graveyards built on London’s then-outskirts to relieve pressure on the capital’s overcrowded and insanitary churchyards and crypts. This progress is, however, still prone to disruption by the unruly (un)dead. It’s interesting that occult and macabre legends are associated with other Magnificent Seven cemeteries. In the 1970s, London and the entire country were gripped by rumours that a vampire lurked in Highgate Cemetery while a myth has grown up about a neo-Egyptian tomb in Brompton Cemetery being a magically powered Victorian time machine. Brompton Cemetery is also said to be haunted by the murdered Victorian actor William Terriss, who is buried there and who also haunts Covent Garden Underground Station.

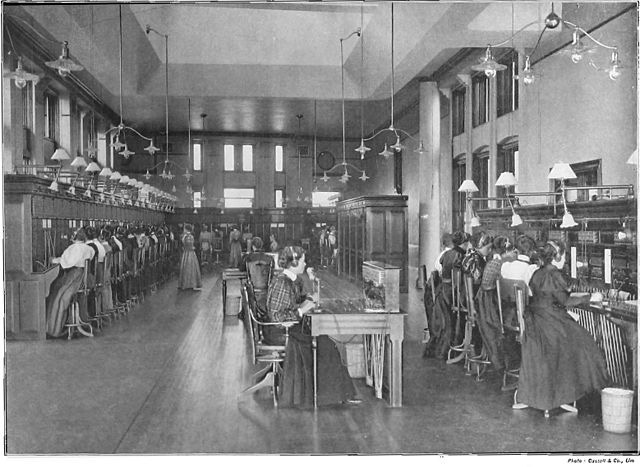

A telephone exchange in Montreal, 1895. At the time of the Kensal Green ghost story, most calls had to be connected through an operator.

Many of the turn-of-the-century anxieties found in the tale of Kensal Green Cemetery and its ghost surface in other gothic literature of the period. Bram Stoker’s Dracula, for instance, is full of social tensions, with its middle-class fears of both the aristocracy and the working class. The book frets over the role of the liberated ‘new woman’ and even has Lucy Westenra – manic with her unleashed vampiric sexuality – breaking from her tomb and roaming an area suspiciously like Highgate. Dracula is also full of the technological advances of the time – telegrams, phonographs, blood transfusions, trains – that contrast strangely with the folkloric powers of stakes, crucifixes and bulbs of garlic.

So, the story of Kensal Green Cemetery and its ghost – as grotesque as it might appear – maybe gives us a window into the priorities and concerns of a different era. The account of this lascivious spook contains within it a range of social, sexual, psychological and technological anxieties. Though now long-buried beneath the clay of time, this absurd yet chilling tale does make one wonder what other things might lie under the patina of the everyday mind, just waiting for the opportunity to be resurrected.

(This article’s main image – showing a gothic tomb in London’s Kensal Green Cemetery – is courtesy of Marathon.)

Leave A Comment