One of the most gothic – and sinister – characters in the work of Charles Dickens is the wealthy recluse Miss Havisham. A bride jilted on the morning of her wedding day, Miss Havisham has withdrawn – in her heartbreak and anguish – into a gloomy world of embittered memories. Since being abandoned, she has refused to take off her wedding dress and the tattered yellowing gown still hangs from her gaunt figure. She still wears her wedding veil and faded bridal flowers in her hair.

Miss Havisham received the letter cancelling her wedding as she was getting dressed (a letter which also revealed her intended had swindled her). She has, thereafter, worn just one shoe, as she’d only managed to put one on before the letter was delivered. All the clocks in Miss Havisham’s house are stopped at twenty-to-nine, the moment she learned of her betrayal. The blinds are kept permanently down, meaning she lives in a candlelit twilight. She’s permitted nothing to be moved since the day she was deserted. The wedding cake and the remains of the bridal banquet are still laid out – rotting, mouldering and stale – on a disintegrating tablecloth. Beetles and spiders lurk among the remnants of the aborted feast. The rooms of Miss Havisham’s decaying mansion, Satis House, are never cleaned or dusted. Grime encrusts the windows – further restricting the penetration of daylight – and dust has piled up on the furniture and floors.

Many people think of Miss Havisham as old, but according to Dickens’s notes, he envisaged her as only in her mid-thirties at the beginning of the novel she appears in, Great Expectations. Dickens, however, implies that the years without sunlight have prematurely aged her. (Dickens obviously didn’t understand the effects of UV rays.) Pip, the hero of Great Expectations – who Miss Havisham lures as a young boy to her mansion while entertaining the possibility of perhaps ruining his life – describes her as looking like ‘some ghastly waxwork at the fair’ or ‘a skeleton in the ashes of a rich dress’. Miss Havisham informs Pip that she is ‘a woman who has never seen the sun since you were born.’ Dickens depicts Miss Havisham as resembling ‘the witch of the place’ while Pip sees the ‘withered bridal dress’ as like ‘grave clothes’ and ‘the long veil so like a shroud’. Miss Havisham is almost vampire-like, with Pip suspecting ‘the admission of the natural light of day would have struck her to dust’. She does perhaps follow the timeless existence of the nosferatu. After Pip’s first visit to Satis House, ‘the rush of daylight quite confounded me and made me feel as if I had been in the candlelight of that strange room many hours.’

Miss Havisham looking skeletal in a 1910 illustration by Harry Furniss

Miss Havisham adopts a girl, Estella, who she at first wishes to guard from suffering a fate such as hers by warning her against the evils of the male sex. She later, however, upon noting how beautiful Estella is becoming, decides to use her protégé as an instrument of revenge against men, rearing her to be cold and manipulative. Pip is one of the unfortunate males to come under Estella’s seductive influence. He falls for her and – unsurprisingly – Miss Havisham’s machinations have dismal consequences for both these young people’s lives.

Miss Havisham is certainly a peculiar character, but it may surprise you to know that many believe she didn’t slide fully formed from the imagination of Charles Dickens. There is said to have been a prototype – a dark figure of London legend – called Jane Lewson. Jane, who died when Dickens was a boy, also lived a secluded life in a gloomy mansion. She permitted no object to be moved and allowed no cleaning to be done. Her windows grew so grimy that she lived in continual dusk. Like Miss Havisham, Jane always wore the same clothes, clothes that appeared so gothically grand that ‘Lady Lewson’ became her nickname. Moreover, it’s claimed that Lady Lewson endured her hermit-like, twilit existence until the incredible age of 116.

But who exactly was Jane Lewson and did she really inspire Charles Dickens to create Miss Havisham? How might Dickens have heard of her? Could there have been other models for Miss Havisham – jilted women who never removed their bridal gowns, who lived as recluses and who never allowed their decades-old wedding feasts to be cleared away? And how might their stories have ended up in Great Expectations?

Keep reading for tales of candles perpetually burning on ancient wedding cakes, skins plastered with generations of make-up and pig fat, macabre takes on feng shui and new teeth freakishly growing in 87-year-old mouths.

The Dusty, Cobwebby, Reclusive and Very Long Life of Lady Lewson – a Model for Miss Havisham?

Jane Lewson was – or so she claimed – born in 1700, in London. Her maiden name was Vaughan and she grew up on Essex Street, off the Strand, with parents she would always emphasise were of the utmost respectability. At 19-years-of-age, Jane married an old and extremely wealthy merchant, taking his surname of Lewson. She moved into his large opulent house in Clerkenwell, a neighbourhood on the city’s then-northern fringes. The district was considered well-to-do, despite the presence of a few undesirables and eccentrics and the looming mass of the notorious Coldbath Fields Prison (now Mount Pleasant Sorting Office). As far as eccentrics were concerned, Jane Lewson was destined to become one of the area’s most famous human oddities.

Jane gave birth to a daughter, but when she was just 26, her husband passed away, with Jane inheriting much of his fortune and his grand house. For a time, Jane and her daughter lived a relatively normal life, with the only – possibly – perplexing thing about Jane Lewson being the fact she rejected so many suitors, all of whom were eager to gain the hand of the young, attractive and very rich widow. Things changed, however, when Jane’s daughter married and she left home to live with her husband. Jane then appeared to embrace solitude. She seldom went out to socialise and welcomed few visitors.

This in itself may not seem so unusual – society has always had its loners and recluses. It was more the whispers about how Jane lived inside her massive gloomy mansion that elevated eyebrows. She allowed nothing to be changed, moved, thrown out, washed or cleaned. The windows acquired a crust of grime, making the rooms duskier, while dust settled as thick as snow on tables, chairs and picture frames. Layers of dirt obscured mirrors and tinted walls. Jane’s hatred of cleaning even extended to her own person. She wouldn’t wash as she believed the grime on her skin shielded her from illness and that exposure to water was the surest way to get sick. Added to this, she’d smear her skin with pig fat each morning – fat that never got washed off – on top of which she’d apply powder and make-up. Believing each greasy layer was further protection against disease, she maintained she had no need for drugs or doctors.

Jane wore the same style of clothes throughout her life, a style which dated back to the reign of George I (1714-27). As the years passed, she began to resemble a person from another era, a time-travelling curiosity. Her neighbours referred to her as ‘Lady Lewson’ as her manner of dress – and the gold-headed cane she clutched – seemed so archaic and grand in the rapidly modernising city. She’d wear ruffs, frills and a long silk gown. Her hair would be piled to the height of half-a-foot around a horsehair frame, with a few curls left dangling, and the whole display would be capped by a large straw bonnet. A black silk cloak trimmed with lace protected her from the elements. This was her costume every day for her last 80 years.

A depiction of Lady Lewson from The Book of Wonderful Characters (1869) – was she a model for Dickens’s Miss Havisham?

As more dirt and generations of cobwebs built up on her windows, Lady Lewson went on insisting they shouldn’t be washed. She feared this would shatter the glass and either kill the person cleaning it or permit germs to be carried in with the outside air. This added to her mansion’s gloom as the filth-coated windows, in her later years, allowed barely a sliver of light in. Lady Lewson stipulated the beds must be kept made up for visitors – visitors she never invited. Some said the same clothes stayed on the beds for years, mouldering and mildewed. Others claimed Lady Lewson had her maids prepare the beds each morning – the only things that got changed in the house – in case the non-existent visitors unexpectedly turned up.

As Jane aged, she got more and more superstitious and her obsession with staving off illness and death deepened. She’d only drink out of one cup, believing this cut the likelihood of her catching a cold. Jane had similar ideas about knives, forks and plates and would only sit on one chair. She became even more insistent that nothing in the house should be moved, believing the mystic alignment of her possessions – in a kind of macabre feng shui – was responsible for her remarkable longevity and robust health. She barely suffered an hour’s illness though she lost her sight towards her life’s end.

Though she seldom ventured outside her property, Jane Lewson did enjoy her garden. She’d sit in it and read and would occasionally invite the few acquaintances she had left alive to come and take tea with her there. They’d sit and discuss ‘old times’. She was reputed to have an excellent memory and loved relating events from the early 1700s. The only journeys out she seems to have made were occasional trips to her local grocery store.

Pip with Miss Havisham inside the gloomy Satis House

The author Edith Sitwell described Lady Lewson as a ‘strange and ancient trumpery’, stating ‘her likeness to a cobweb is produced by the fact she wears the “ruffs and cuffs and fardingales” of her youth.’ In what seemed a further defiance of the natural order, Lady Lewson ‘at the age of 87 cut two new teeth, which were a source of pride to her and of wonder to her neighbours.’

Edith Sitwell continued, ‘Her large house in Coldbath Square contains only four other beings, ghosts like herself, two lapdogs, an aged cat, and an old man whose occupation had been that of wandering from house to house in the district earning pieces of food by running errands and cleaning boots.’ This man acted as her cook, butler and – by that time – sole servant.

Death Finally Lays His Skeletal Hand on Lady Lewson’s Shoulder

Many had likely begun to think of Lady Lewson as immortal. However, the sudden passing of an – also aged – neighbour in spring 1816 led her to shiver and realise her own appointment with death must come. The shock of her neighbour’s demise caused Jane to weaken. She became bedridden, refused medical help, and on Tuesday 28th May died at what she claimed was the age of 116. On June 3rd, she was buried in the famous dissenters’ graveyard Bunhill Fields, which contains the remains of Daniel Defoe and William Blake among other luminaries.

After Jane’s death, her house was opened to the curious, who must have gaped at its ancient, dust-shrouded artefacts. One Mr Warner was astonished by the lengths Jane had gone to in order to keep out germ-bearing intruders. Warner noted that strong boards – bound together with iron bars – reinforced the ceiling of the upper storey.

Jane Lewson’s fame is attested by the fact that obituaries to her appeared in several publications, including The Observer. The obituaries stressed she’d died at the age of 116 and had lived through the reigns of five monarchs. She was taken to Bunhill Fields in a grand hearse pulled by four horses. Two other carriages accompanied it, containing her executor and a few relations, relations she’d always refused to see.

So might Jane Lewson have been Dickens’s model for Miss Havisham? Dickens was only four when Lady Lewson died, but her story was well-known in London and it’s likely Dickens heard it growing up. Jane Lewson – who today might be diagnosed as suffering from obsessive compulsive disorder or anxiety or a hoarding syndrome or some phobia – certainly resembles Miss Havisham in her reluctance to have things cleaned or rearranged, in her always wearing the same clothes (though not a wedding gown) and her reclusiveness. However, Jane did marry and was not a jilted bride. She gave birth to, rather than adopted, a daughter and there’s no evidence she raised her child to take revenge on men. Contrary to common perceptions, Lady Lewson’s advanced age also isn’t reflected in the Miss Havisham character, a woman Dickens envisaged as in her early middle years.

Could there, then, have been other models that Dickens based Miss Havisham on rather than – or at least in addition to – Jane Lewson? Let’s find out below.

Might Charles Dickens Have Based Miss Havisham on an Australian, Eliza Emily Donnithorne?

Miss Havisham with Pip and Estella in Great Expectations

One possible candidate for Miss Havisham was an Australian woman, Eliza Emily Donnithorne (1821-1886). Eliza was born in South Africa and spent much of her childhood in Calcutta, India, where her father served as master of the mint and as a judge. When Eliza was about 17, her father relocated to Sydney, Australia, where Eliza later joined him. They lived in Cambridge Hall (later Camperdown Lodge) and when Eliza’s father died in 1852, he left her most of his estate.

Though evidence for Eliza’s story is scanty, most accounts claim that – at the age of about 30 – she was jilted on her wedding day. Her fiancé – some sources identify him as George Cuthbertson, a shipping clerk – failed to turn up at Cambridge Hall for the wedding breakfast. According to local legend, the distraught Eliza commanded that the feast and decorations should not be cleared away. After the embarrassed guests had left, Eliza had the blinds pulled down. They were never raised again, meaning she’d always live in semi-darkness. She spent the remainder of her life as a recluse amidst the decaying food and tattered streamers. Eliza never took off her wedding dress.

She had the front door chained, meaning it would only open a couple of inches. Callers therefore never saw her as – if she really was forced to answer the door – she could stay out of view. She never heard from Cuthbertson again and – when she died 30 years after being jilted – those who came to collect the body found her still attired in her wedding gown. Dust lay deep on the floor and grime encrusted the windows. In the dining room were the remnants of the three-decade-old wedding banquet – heaps of mouldy crumbs.

Eliza Emily Donnithorne was buried next to her father in St Stephen’s Churchyard (now Camperdown Cemetery), in the Sydney suburb of Newtown. Since the 1890s, many Australians have maintained that she inspired the Miss Havisham character, meaning her grave is one of the most visited in the necropolis. When vandals attacked the grave in 2004, the Australian National Trust and the UK Dickens Society funded most of the restoration work.

The grave of Eliza Donnithorne and her father James in Camperdown Cemetery, Sydney (Photo: TTaylor)

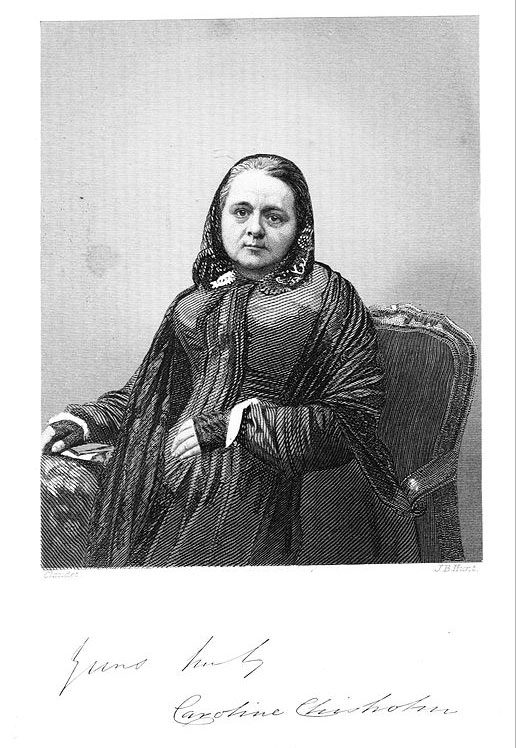

As Dickens never visited Australia, we might ask how he came to know about Eliza’s story. Dickens did follow events in the Australian colonies and discussed them in his weekly magazine Household Words. One 1935 newspaper article claimed Eliza’s father was ‘a great friend of the famous writer’, but gave no evidence to back this statement up. A more likely way of Dickens hearing about Eliza was through an Australian correspondent, one Caroline Chrisholm. Chrisholm – a humanitarian and social reformer – supplied Dickens with Australian news and Dickens published some of her articles in Household Words. Chrisholm could well have been acquainted with the Donnithorne family or at least known people close to them. She ran a shelter for young female immigrants in Newtown, near the Donnithorne home, and Chrisholm and her husband seem to have been involved in the same Sydney social circle as Donnithorne’s father. Chrisholm and Eliza Donnithorne were also once patients of the same doctor.

Caroline Chrisholm herself at least partly inspired a Dickens character – Mrs Jellyby in Bleak House. Mrs Jellyby – a busybody and inept do-gooder – takes on a variety of social causes with obsessive enthusiasm while neglecting her family. The most preposterous of these, Dickens implies, is her insistence on campaigning for votes for women. Chrisholm’s efforts were, however, at least impressive to some as she is considered a saint in the Anglican Church and is being considered for sainthood in the Catholic Church too, a religion she converted to when she married at 22-years-of-age.

Caroline Chrisholm – did she tell Dickens the story of Eliza Emily Donnithorne, on whom he then based Miss Havisham?

The problem with the claim that Eliza Emily Donnithorne was the model for Miss Havisham is that little is known for certain about Eliza’s life. An interesting take on her legacy, expounded in Evelyn Juers’ 2012 book The Recluse, is that – rather than Eliza inspiring the Miss Havisham character – Dickens’s depiction of Miss Havisham attached itself to Eliza’s legend after her death. Eliza’s story, therefore, became increasingly embroidered with details from Great Expectations as time went on.

Other Prototypes for Miss Havisham – the ‘Wealthy Recluse’ Elizabeth Parker and Margaret Catherine Dick

Many claim that – while staying at the Bear Inn in Newport, Shropshire – Charles Dickens heard a story that would inspire the figure of Miss Havisham. It’s said that one Elizabeth Sarah Parker (1802-1884), of Chetwynd House, Newport, became a recluse after being jilted by Sir Baldwyn Leighton on her wedding day. Following this traumatic experience, Miss Parker spent the rest of her life secluded in the upper storey of Chetwynd House while the ground floor remained bare and unfurnished. Except one room, that is. This room, which never saw daylight, contained her mouldering wedding cake, on which candles were kept continuously burning. Elizabeth only came out of her retirement once. She attended a ball in Newport clad in her wedding dress – because it was wrongly rumoured Sir Baldwyn Leighton would be there. Elizabeth Sarah Parker died in June 1884 and was buried in Chetwynd Church.

This intriguing story has, however, been subjected to some significant myth-busting. Extensive research by Newport archivist Linda Fletcher, in collaboration with the Dickens Fellowship, has unearthed no evidence of either Dickens visiting Newport or of Elizabeth Sarah Parker being the model for Miss Havisham. The letters and papers of the gossipy Newport researcher T.W. Picken (1834-1919) show no mention of any visit from Charles Dickens, even though such a visit would have happened during Picken’s time. A search of all of Dickens’s diaries, letters and journals has also revealed no references to trips to Newport. In addition, Miss Parker was living in Chester or Whitchurch rather than Newport at the time Dickens was writing Great Expectations and she didn’t move to Chetwynd House until she was around 60, after Great Expectations had been published. As for Sir Baldwyn Leighton, he actually married Elizabeth’s older sister, Mary, and there’s no evidence Elizabeth abandoned public life. Perhaps – as may have been the case with Eliza Emily Donnithorne – the details of Dickens’s Miss Havisham entwined themselves around memories of Elizabeth after her death.

The ghostly remains of Miss Havisham’s wedding banquet in Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations

Another possible prototype for Miss Havisham was Margaret Catherine Dick (1827-78) from the village of Bonchurch, on the Isle of Wight. Dickens spent the summer of 1849 in Bonchurch, working on David Copperfield, and got to know quite a few of its inhabitants. He dined with the Dick family at their house, Uppermount, and he’s said to have based the character of the harmless madman Mr Dick on Margaret’s father Samuel (or at least used his name).

Margaret Dick was jilted at the altar in Holy Trinity Church, in the nearby settlement of Ventor, in 1860. She thereafter left the family home and lived as a recluse at a house called Madeira Hall. Another Bonchurch woman, Catherine Haviland, may have supplied the name for the Miss Havisham character. Catherine moved to the Bonchurch area in 1852, living opposite Madeira Hall. The well-to-do Miss Haviland had a coach house and stables built, a building now called Haviland Cottage. A similar structure is mentioned as the coach house of Satis House in Great Expectations. Dickens returned to Bonchurch in November/December 1860 and it’s almost certain that he would have heard from his acquaintances about both Margaret Dick’s jilting and Miss Haviland’s arrival in the village. One possible objection to this theory is that the serialisation of Great Expectations began in the magazine All Year Round on 1st December 1860. This would make the timeframe from inspiration to publication incredibly tight, but it seems Dickens did write many of the novel’s episodes during the serialisation process and he may well have heard about goings-on in Bonchurch through letters prior to his trip there. Margaret Dick died in 1878 at the age of 52 and was buried in nearby Ventor Cemetery.

So Who Did Inspire Charles Dickens to Create Miss Havisham – Lady Lewson or Some Other Reclusive Woman?

I suspect much of the input for Dickens’s depiction of Miss Havisham did indeed come from tales of Lady Lewson. Much about Jane Lewson fits the Miss Havisham narrative – the long years of solitude in a badly lit, decaying, filthy mansion; the continual wearing of the same archaic clothes; the obsessive refusal to allow anything in the house to be changed. As Lady Lewson was not, however, a jilted bride, Dickens perhaps also found inspiration elsewhere. Of the other stories detailed above, it seems most likely he would have drawn from that of Margaret Catherine Dick in Bonchurch, especially as he had knowledge of that village’s gossip. Maybe he combined Margaret’s broken-hearted retirement with the retreat of Lady Lewson into an odd world of gloom and dust and things that can never be moved or cleared away. It’s also possible – if the story of Eliza Emily Donnithorne was true, rather than being embellished with Dickens’s own imaginings after her death – that Dickens may have taken inspiration from the letters of his Australian correspondent Caroline Chrisholm.

The narrative of Miss Havisham in Great Expectations does, however, have one significant difference to the tales of all the women presented here. The women above remained in their sombre solitude until they died of natural causes – mostly at ages which, for the time, would have been considered reasonably good lifespans. And Jane Lewson, of course, is reputed to have lived to an age that would be incredible even today. This was not the case with Dickens’s fictional Miss Havisham.

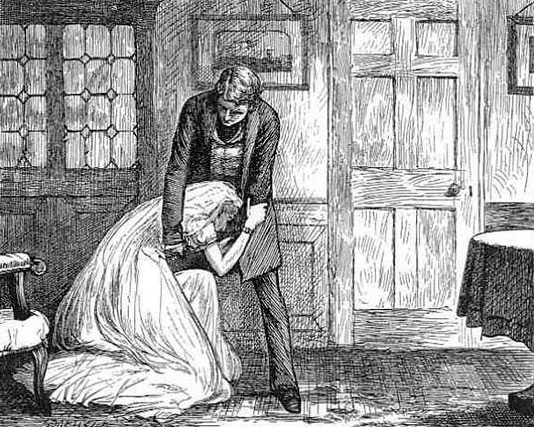

The final time Pip visits Miss Havisham, she – realising what she has done to him and Estella – throws herself at his feet, hugging his legs and begging him to forgive her. A startled Pip thinks, ‘And could I look upon her without compassion, seeing her punishment in the ruin she was in, in her profound unfitness for this earth on which she was placed, in the vanity of sorrow which had become a master mania, like the vanity of penitence, the vanity of remorse, the vanity of unworthiness, and other monstrous vanities that have been curses in this world?’

Miss Havisham begs Pip’s forgiveness, in an 1877 edition of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations

As he’s leaving the grounds of Satis House, Pip looks back and sees ‘her seated in the ragged chair upon the hearth close to the fire, with her back towards me. In the moment when I was withdrawing my head to go quietly away, I saw a great flaming light spring up. In the same moment, I saw her running at me, shrieking, with a whirl of fire blazing all about her, and soaring at least as many feet above her head as she was high.’

Sprinting up the stairs and back into her room, Pip ‘dragged the great cloth from the table … and with it dragged down the heap of rottenness in the midst.’ With the mouldering table cloth – in the process burning his own hands – he covers Miss Havisham, trying to put out the flames as ‘patches of tinder yet alight were floating in the smoky air, which, a moment ago, had been her faded bridal dress. Then I looked around and saw the disturbed beetles and spiders running away over the floor, and the servants coming in with breathless cries.’

A surgeon is summoned and, though Miss Havisham is badly burnt, he judges her condition ‘far from hopeless’. He has her laid on the ‘great table’, the table that had so recently borne her wedding feast, ‘which happened to be well-suited to the dressing of her injuries.’

‘Though every vestige of her dress was burnt …’ Pip narrates, ‘she still had something of her old ghastly bridal appearance; for, they had covered her to the throat with white cotton wool, and as she lay with a white sheet loosely overlying that, the phantom air of something that had been and had changed was still upon her.’ Miss Havisham lingers on for a few weeks and – though for a time it seems she is improving – she relapses and dies.

It’s interesting that Dickens has Miss Havisham exit the book in this way. Though he obviously had compassion for the character, there was something about the unnaturalness of her lifestyle and her long-cherished resentments that made her seem like a ghost, a vampire or – as Dickens put it – a witch. Perhaps burning was the only way in which Dickens felt this eerie figure – and the strange mouldering world of decay and stopped time she had built up around her – could finally be exorcised.

(This article’s main image – showing Miss Havisham in her mouldering wedding dress – is courtesy of DeseretNews)

Thank you for highlighting Margaret Dick / Catherine Haviland as the inspiration behind Miss Havisham. We published a blog on our Bonchurch research in March 21. This goes into much more detail , and in particular covers the months in 1860 , when two of Dickens daughters spent months in Bonchurch looking after the Rev James White’s dying daughter.

Many thanks for your comment, Alan. It’s always fascinating to try to disentangle the inspirations for literary characters.

Such an interesting article with amazing research on possible candidates for Dickens’ Miss Havisham. Merci for your research and vivid, memorable words,

You’re welcome, Lisa.

Fascinating read! Thank you so much for the lengths of research you’ve gone to. A character with such emotional depth

Thanks, Becky, glad you enjoyed the article.

Another absolutely amazing read about my favourite Dickens novel…so engrossing. Jane Lewson’s life is beyond fascinating and is surely the front runner for the greatest recluse of all time? I think the scene of Miss Haversham catching fire is perhaps the most terrifyingly brilliant moment in English literature (Ok, quite a lordly statement, I realise!) apart from the way Dickens walks us in to the discovery of her ruination amidst the debris of the wedding feast. I think Martita Hunt did a superb job of playing Miss Haversham (my husband pointed out to me the ‘have a sham’ play on words here! Though Havers-ham and Havil-land have great similarities….!) Anyway, thanks for another really great article!

Many thanks, Joanna, glad you enjoyed my musings on Jane Lewson and Miss Havisham

Sorry to reply late. I’d heard that Miss Haversham was based on a man. I can’t remember his name but he’s the person who the Dirty Dick’s pub near Liverpool Street Station is called after. Miss Lewson does seem a likely candidate for the inspiration I must admit. Right gender, right back story.

Hi Patricia, I’d never heard the claim that Miss Havisham was based on a man or about the connection with Dirty Dicks. Sounds interesting – I’ll have to look into it.