One of the weirdest substances in medical history – a substance Europeans once slathered on rashes and wounds and gulped down in drinks – was known as mummia. The word ‘mummia’ has a resonance of Egypt about it and that was where this medicine came from. It was – simply put – produced by grinding up Ancient Egyptian mummies and was credited with healing a staggering range of ailments. The European mania for mummia began in the early 1100s and by the 16th century it was one of the most common drugs in apothecaries’ shops across the continent.

Physicians, alchemists and surgeons brimmed with praise for the substance. The philosopher and pioneering scientist Francis Bacon (1521-1626) declared ‘mummy hath great force in staunching of blood’. Robert Boyle (1627-91) – the ‘father of modern chemistry’ – believed mummia was ‘one of the most useful medicines commended and given by our physicians for falls and bruises’. Mummia, it was claimed, could heal sicknesses as diverse as coughs, ‘pungent pains of the spleen’, hysteria, diarrhoea, ‘inflammation of the body’ and epilepsy, as well as aiding childbirth. The French king François I (1494-1547) took a pouch with him everywhere containing a mix of mummia and pulverised rhubarb. François feared ‘no accident if he had a little of that by him’ and asserted his weird concoction could deal with headaches, stomach upsets and even fractured bones.

A jar for mummia from an 18th-century apothecary’s shop. (Photo: Bullenwachter)

But Europeans weren’t just content with making ointments from millennia-old mummies or swallowing their powdered remnants in wine. The art world also sought mummia out. Painters prized a pigment made from the substance called mummy brown. A rich brown hue – which fell between the shades of burnt and raw umber – mummy brown was said to be good for glazes, shadows, shading and (yes) flesh tones. Mummy brown was popular among the Pre-Raphaelites and was available in London art shops as late as the 1960s.

But how did the outlandish and revolting idea arise that ancient human flesh could soothe health problems? Was everybody always convinced of mummia’s curative properties and when did learned opinion start to doubt the drug’s wholesomeness? What well-known paintings feature the macabre substance and why did artists eventually stop daubing the remains of ‘priests and Pharaohs’ onto their canvases?

Read on to learn of paints made from pulverised French monarchs, of aristocratic parties at which mummies were ‘unrolled’ before enraptured audiences, and of a mysterious lifeforce some believed could be transferred from mummy to patient. Continue reading to find out why mummia’s critics condemned it as a ‘diet of dismal vampirism’ and how one compassionate painter even gave a solemn burial to a tube of mummy brown.

Did the Obsession with Mummia Arise from Translation Blunders and Scientific Mistakes?

The idea that mummies could be ground down into a cure-all drug is certainly a strange one. Though the Ancient Egyptians were mummifying humans and animals as long ago as 3000 BC, mummified remains didn’t become a feature of European medicine until the High Middle Ages. The craze for mummia seems to have at first evolved from a more innocent and – somewhat – less disgusting source: an interest in the medical properties of bitumen.

Bitumen is a naturally occurring, pitch-like mineral (a form a petroleum or asphalt) that bubbled up from a few spots in the Near and Middle East. The Greeks – and others in the Ancient World – believed bitumen had therapeutic qualities. Proclaimed as a treatment for conditions ranging from dysentery to toothache, bitumen was extolled by such weighty authorities as the Roman historian and naturalist Pliny the Elder and the Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides. Arab and Persian doctors later used bitumen for ailments including cuts, bruises, bone fractures, stomach ulcers and tuberculosis. During the Crusades, European soldiers learned of the drug’s remarkable attributes, especially its efficacy in healing cuts and fractures. They carried this knowledge home, thereby making demand for bitumen soar. This – combined with the scarcity of the mineral – created a problem of supply. The few sites where the substance seeped from the earth – such as a mountain in Persia and the floor of the Dead Sea – were unable to satisfy the new European appetite for the medicine.

Natural bitumen collected from the shore of the Dead Sea – the original mummia? (Photo: Daniel Tzvi)

People, then, began to search for alternative sources of this rare – and increasingly costly – mineral. The Ancient Egyptians were known to have used bitumen as an embalming agent – they’d indeed applied it to their dead from the Twelfth Dynasty (1991-1802 BC) onwards. The idea, therefore, arose that the commodity could be obtained by rifling ancient tombs and scraping the substance from their long-dead tenants.

The Arab physician, historian and philosopher Abd’ el-Latif al-Baghdadi (1162-1231) bears much responsibility for popularising this notion. Latif wrote of a substance that ‘in the belly and skull of these corpses is also found in great abundance called mummy’. (Mum or mumiya – the Persian word for bitumen – is where the English word ‘mummy’ comes from.) Although Latif stressed the term ‘mummy’ usually denoted bitumen that had oozed from the ground, he added, ‘The mummy found in the hollows of corpses in Egypt differs but immaterially from the nature of mineral mummy; and where any difficulty arises in procuring the latter, may be substituted in its stead.’ It seems Latif, however, confused the sludgy black liquid that occasionally seeps from embalmed corpses with the bitumen the Egyptians used as a preserving agent. In reality, the two are different substances.

Refined asphalt or bitumen – the Ancient Egyptians used ‘mummia’ of this sort to help preserve their dead. (Photo: Burger)

Some European writers and translators made a rather different error. Instead of, like Latif, believing that mineral bitumen could be salvaged from ancient mummies, they thought the health-giving ‘mummia’ was actually produced by the mummies themselves. The Italian translator Gerard of Cremona (1114-1187) erroneously defined the Arabic word mumiya as ‘the substance found in the land where bodies were buried with aloes by which the liquid of the dead, mixed with aloes, is transformed, and it is similar to marine pitch.’ In his translation of the 12th-century Arab physician Serapion the Younger, Simon Geneunsis (died 1303) wrote, ‘Mummia, this is the mummia of the sepulchres with aloes and myrrh mixed with the liquid (humidiate) of the human body.’ According to Matthaeus Platearius – a teacher at the medical school in Salerno and author of the popular herbal manual Circa Instans – ‘Mummia is a spice found in the sepulchres of the dead … That is best which is black, ill-smelling, shiny and massive.’

Over time, these mistakes were compounded, with people coming to think of mummia as not just the hardened secretions of the corpse or its residues of bitumen, but as the dried embalmed flesh of the whole cadaver. Therefore, any Ancient Egyptian mummy could be ground down to make the in-demand drug. (The fact that mumiya in Arabic can mean both ‘the kind of bitumen used medically’ and ‘a bitumen-embalmed body’ may have added to this confusion.) The Italian surgeon Giovani da Vigo (1450-1525) described mummia as: ‘The flesh of a dead body which is embalmed, and it is hot and dry … it has virtue to heal over wounds and staunch blood.’

Such errors, not surprisingly, led to a scramble to acquire Ancient Egyptian corpses. The age-old dead became a prized commodity. Let’s take a look at how this gruesome trade manifested itself and how some mummia might not have been quite as ancient or authentic as those gulping it down or rubbing it on their wounds would have liked to believe.

The Heyday of Mummia and the Disreputable Trade in Medicinal Mummies

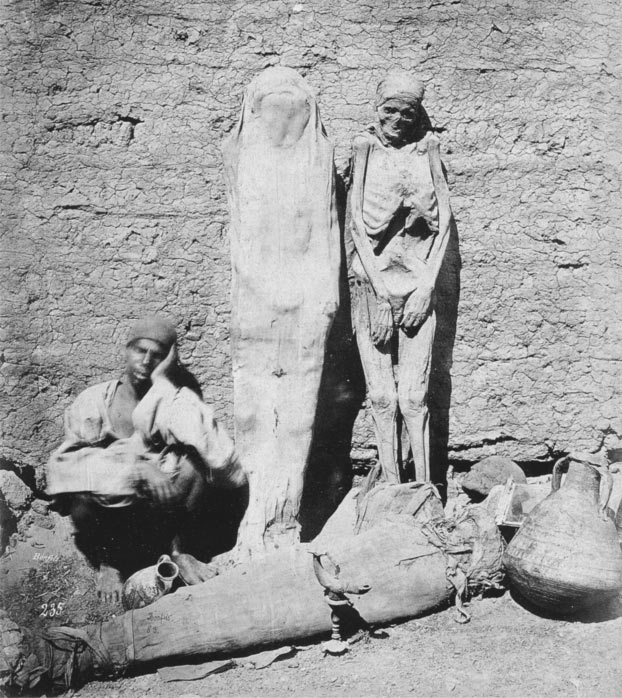

By the 1500s, merchants – Spaniards, Frenchmen, Britons, Germans and others – were making massive profits shipping mummies, whole or in parts, out of Alexandria and Cairo. Both Egyptians and foreigners ransacked tombs seeking the lucrative cadavers.

In 1586, the London merchant John Sanderson – an agent for the Turkey Company – described the hunting out of the precious sources of mummia: ‘We were let down by ropes, as into a well, with waxe-candles burning in our hands, and so walked upon the bodies of all sorts and sizes … they gave no noisome smell at all … I broke off all the parts of the bodies to see how the flesh was turned to drugge, and brought home divers heads, hands, armes and feet, for a shew: we brought also 600 pounds for the Turkie Company in pieces; and brought into England in the Heracles: together with a whole body: they are lapped in above a hundred double of cloth, which rotting and pilling off, you may see the skin, flesh, fingers and nayles firme, altered blacke. One little hand I brought into England, to shew; and presented it to my brother, who gave the same to a doctor in Oxford.’

The diarist Samuel Pepys wrote in 1668 of seeing an Egyptian mummy in London before it was ground into powder: ‘And so parted, I having seen a mummy in a merchant’s warehouse there, all the middle of the man or woman’s body black and hard. I never saw any before, and, therefore, it pleased me much, though an ill sight; and he did give me a little bit, the bone of an arme.’

A mummy dealer in Egypt, photographed in 1875

The demand for mummia was, however, so phenomenal that Egypt’s once plentiful reserves of ancient corpses were being depleted. The temptation was, therefore, great for traders to offer mummies of a much more recent vintage. As early as 1564, the French physician Guy de La Fontiane – who worked for the King of Navarre – examined around 40 mummies held by a Jewish dealer in Alexandria. La Fontiane found many had been manufactured from recently deceased individuals, such as executed criminals and slaves. The corpses had been coated and filled with bitumen then exposed to the sun to create mummified tissue.

Another merchant, when asked if any of his mummies had died of horrific illnesses, said he ‘cared not whence they came, whether they were old or young, male or female, or of what disease they had died, so long as he could obtain them … when embalmed no one could tell.’ Traders sometimes even sold non-human remains. Mummified ibises could masquerade as ‘mummified children’ while other mummies incorporated camel flesh. According to Pierre Pomet’s A compleat history of drugges (1712), some mummies were made from the sun-dried bodies of travellers who’d been caught in sand storms.

Despite the dubiousness of many of the mummies that reached Europe, much medical opinion remained enthusiastic about mummia. Two fistfuls of the powder could, apparently, help with epilepsy, vertigo and palsy. Mummia – soaked in wine and turpentine – could act as a ‘counter-poyson’ and guard against plague and ‘all manner of infection’. According to Bechler’s Parnassus Medicinalis (1663), ‘Mummy dissolves coagulated blood, relieves cough and pain in the spleen, and is very beneficial in flatulency and delayed menstruation.’

A wooden container for mummia from the collection of an apothecary, displayed in Hamburg Museum, Germany. (Photo: Christoph Braun)

The physician John Hall – the son-in-law of none other than William Shakespeare – treated a patient’s epilepsy by getting them to inhale the smoke of ‘a mixture of aromatic resin, powdered mummy, black pitch and juice of rue’. Catherine de Medici, the Queen Consort of France, was so convinced of the curative effects of mummia she sent her physician to Egypt in 1549 to obtain a supply. Among the many medical problems mummia was said to ease were withering and contractions of the joints, ‘hardness of the cicatrices’ (the scars of old wounds), catarrh, the marks left by measles, difficult labours and diseases of the head.

We might wonder why, beyond mummia’s association with bitumen, people ascribed such wondrous health benefits to ingesting powdered pieces of Egyptian cadavers. There seems to have been an idea that mummies contained a mystical lifeforce that could boost the vitality of ailing patients. This, no doubt, partly came from the widespread notion that the Ancient Egyptians had understood many occult secrets and mysteries of the cosmos, an understanding they particularly expressed through their rituals of death, mummification and burial. But there also seems to have been a more general idea that by consuming a being’s flesh, a person could take on that being’s attributes. Eating the meat of a bear, for instance, could give you something of that creature’s courage and strength. The influential 16th-century Swiss alchemist and physician Paracelsus propagated this notion and felt the principle also applied to our own species. He, however, recommended medicine made from fresh corpses rather than ancient mummies, stating, ‘If doctors were aware of the power of this substance, no body would be left on the gibbet for more than three days.’

A disciple of Paracelsus, Johann Schroder – physician, pharmacologist and the first person to recognise that arsenic is an element – entertained similar beliefs. Schroder advocated gulping down medicine made from ‘the cadaver of a reddish man (because in such a man the blood is believed to be lighter and so the flesh is better), whole, fresh without blemish, of around 24-years-of-age, dead of a violent death (not of illness), exposed to the moon’s rays for one day and one night.’ The flesh should be treated so that it ‘resembles smoke-cured meat, without any stench’. Oswald Croll – an alchemist and professor of medicine at the University of Marburg – stated that mummia wasn’t ‘the liquid matter which is found in Egyptian sepulchres’ but argued it should be acquired from ‘the flesh of a man that perishes a violent death’. He had a recipe for making the substance from the body of a young red-headed man who’d been bludgeoned on a breaking wheel, hanged and exposed to the air for several days. Croll recommended the flesh should be chopped into small pieces, sprinkled with powdered myrrh and aloes, marinated in wine then dried.

Some writers, on the other hand, felt the best medicine was procured from young ‘unsullied’ females. In the early 1600s, the physician Pietro de la Valle claimed the best mummia came from ‘maidens and bodies of virgins’. As late as 1824, the French writer and historian Jean-Baptiste-Bonaventure de Roquefort concurred with this opinion. In Shakespeare’s Othello, Desdemona’s handkerchief is ‘dyed in mummy which the skilful conserved of maidens’ hearts.’

Despite authorities stating that good mummia could be obtained in Europe itself, the mystic lure of Ancient Egypt was strong and recent European corpses were often passed off as originating from the land of the Pharaohs. The barber surgeon Ambroise Paré (1510-90) – a royal doctor and one of the ‘fathers of modern surgery’ – exposed the production of fake mummia in France, finding that apothecaries had been stealing the corpses of executed convicts, putting them in ovens and selling the dried flesh. Paré also came across similar practices in Egypt. One merchant, who confessed to making mummies from the recently departed, expressed astonishment that Christians ‘so dainty-mouthed could eat the bodies of the dead’.

Many European Christians, though, were in agreement with the conman Paré interviewed, feeling mummia was a disgusting and dangerous medicine. Read on to learn of how Shakespeare and other playwrights disparaged the drug, of the doctors and preachers who ranted against it, and of how precious Egyptian mummies gradually came to be put to a more exhibitionistic use.

The Questioning of Mummia’s Health-bestowing Benefits, Shakespeare’s Disapproval and the Stripping of Mummies for Show

Paré admitted to administering mummia to at least a hundred of his patients, but he was to become critical of the medicine. He thundered against ‘this wicked kind of drugge’ that not only ‘doth nothing to help the diseased’ but could actually be injurious to the health, causing ‘many troublesome symptomes, such as paine of the heart or stomacke, vomiting and stinke of the mouth’. Paré stopped prescribing mummia and urged other doctors to do likewise. Renaissance scholars were also becoming aware of the translation mistakes that had sparked much of the enthusiasm for mummia. The French naturalist Pierre Belon (1517-1564) pointed out that when Arab physicians had written of mummia, they’d been referring to pissasphalt (mineral pitch or asphalt) rather than the scrapings of ancient corpses or the powdered remains of bodies dried in the sun. In 1597, the English herbalist John Gerard also stressed that ‘mummia’ was in reality pissasphalt and accused the translator of Serapion the Younger of describing the drug ‘according to his owne fancie’. In 1599, the preacher Richard Hakluyt lamented that ‘these dead bodies are the mummie which the Phisitians and Apothecaries do against our willes make us to swallow.’

The philosopher Sir Thomas Browne in 1658 launched a blistering critique of the trade in mummia: ‘The Egyptian mummies, which Cambyses or time hath spared, avarice now consumeth. Mummie is become Merchandise, Mizraim cures wounds, and Pharaoh is sold for balsams … Surely such diet is dismal vampirism; and exceeds in horror the black banquet of Domitian, not to be paralleled except in those Arabian feasts, wherein Ghouls feed horribly.’ In 1546, the German physician Leonhard Fuchs complained about people ingesting ‘the gory matter of cadavers received evidently from the gallows or the torture wheel, spotted with the faeces of corpses in place of aloes and myrrh.’

A distaste for mummia can also be found in Renaissance literature and drama. In Macbeth, Shakespeare – despite his son-in-law’s enthusiasm for the substance – has his witches add ‘witches’ mummy’ to their diabolical cauldron along with unsavoury ingredients like ‘gall of goat’, ‘eye of newt’, ‘tongue of dog’ and ‘finger of birth-strangled babe’. In James Shirley’s The Bird in a Cage (1633) a character exclaims, ‘Make a mummy of my flesh and sell me to the apothecaries’. In Ben Johnson’s Volpone, it’s also suggested that a body should be sold ‘for mummia, he’s half-dust already’. Perhaps the most gruesome mummia-related lines come from John Webster’s The White Devil:

‘Your followers

Have swallowed you, like mummia, and being sick

With such unnatural and horrid physic,

Vomit you up i’ th’ kennel.’

Despite the disapproval of certain physicians, writers and intellectuals, the medical use of mummia only declined gradually as more scientific and less mythical modes of thinking seeped into society. Mummia’s popularity may have also dipped thanks to suspicions the drug exacerbated plague outbreaks in the 1600s. Another factor may, however, have been changing notions regarding the value of Ancient Egyptian mummies and artefacts.

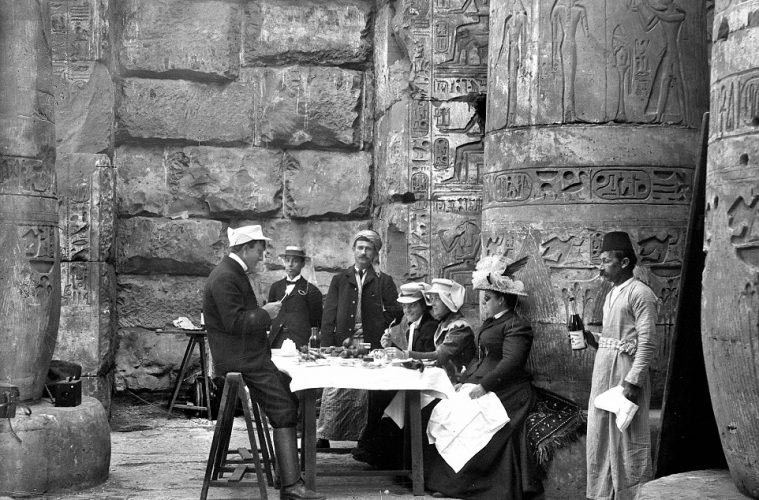

Towards the end of the 18th century, the colonial opening up of Egypt and advances in archaeology led to ‘Egyptomania’ – an obsession with Ancient Egypt that swept across Europe. Egyptian themes featured in operas, novels and plays; Egyptian designs appeared on crockery, jewellery and furniture; and Egyptian-influenced mausoleums – including miniature pyramid tombs – sprang up in churchyards and cemeteries. Mummies themselves became desirable possessions rather than primarily being seen as sources of a drug, a drug which was anyway viewed with more and more scepticism. Tourist trips to Egypt increased and many of these tourists were determined to bring back souvenirs of ancient pedigree. Bits of Egyptian mummies had long been considered collectable – as we’ve seen from the attitudes of Samuel Pepys and John Sanderson – and would sometimes form part of a gentleman’s ‘cabinet of curiosities’. In 1639, an observer described one such collection as containing two ribs of a whale, a preserved pelican, the hand of a mermaid and the hand of a mummy. But as Egyptomania took hold – especially following Napoleon’s invasion of the country in 1798 – this thirst for mummified artefacts intensified.

Victorian tourists relax in Egypt, around 1890

In his Egypt of the Pharaohs (1974), Brian Fagan reports that ‘diplomats and tourists, merchants and dukes, all vied with one another to assemble spectacular collections of mummies and other antiquities.’ This obsession resulted in ‘ferocious rivalry, and the competitors could frequently be seen clambering over stones and broken sarcophagi, rooting through rubble and bartering with boys whose pockets were stuffed with ancient remains.’ Egyptian entrepreneurs had once supplied mummies of dubious antiquity to Europeans eager to make medicine. Now local businessmen reacted to the tourist influx by scattering visitor hotspots with mummies and artefacts transported from elsewhere to make sure that no travellers left disappointed. In 1833, the French abbot Father Géramb commented, ‘It would hardly be respectable, on one’s return from Egypt, to present oneself without a mummy in one hand and a crocodile in the other.’

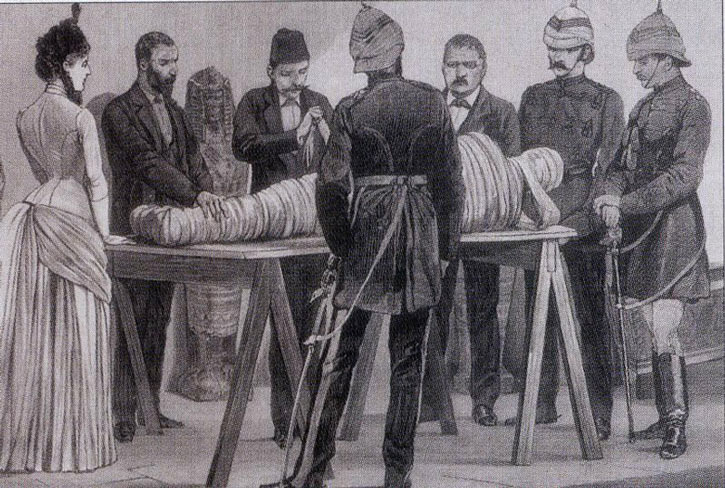

But mummies could have an even more bizarre use than decorating aristocratic houses or furnishing gentlemen’s curiosity cabinets. They could prove quite a social attraction as the centrepiece of ‘mummy unrolling’ occasions. These events would consist of an ‘expert’ – usually a doctor or academic – divesting a mummy of its bandages in front of a fascinated audience. The unwrappings could range from sober sessions in lecture rooms to little more than ghoulish sources of entertainment at private parties. Often the unrollings would be something in between, combining a concern for education and science with elaborate showmanship. Thomas ‘Mummy’ Pettigrew – a surgeon, author, antiquarian and treasurer of the British Archaeological Society – started unrolling mummies and conducting autopsies upon them in a lecture theatre in London’s Charing Cross Hospital. Soon, however, he was unwrapping the ancient cadavers at private gatherings and public exhibitions – events which almost always sold out and had people turned away at the door. By 1848, Pettigrew was thought to have unrolled as many as 50 mummies.

The Egyptologist and folklorist Margaret Murray and her team unwrap the mummy of Khnum-Nakht in front of 500 people in a University of Manchester lecture theatre in 1908.

These mummy-unrolling rituals weren’t limited to England. The French novelist and critic Théophile Gautier attended a mummy unwrapping in 1857. He noted the ‘faint, delicate odour of balsam, incense and other aromatic drugs’ and how ‘a vast quantity of linen filled the room, and we could not help wondering how a box which was scarcely larger than an ordinary coffin had managed to hold it all.’ Gautier was shaken by the mummy’s eyes: ‘two white eyes with great black pupils shone with fictitious life between brown eyelids. They were enamelled eyes, such as it was customary to insert in carefully prepared mummies. The clear, fixed glance, gazing out of the dead face, produced a terrifying effect; the body seemed to behold with disdainful surprise the living beings that moved around it.’ Théophile related how ‘little by little the body began to show its sad nudity … is it not a surprising thing … to see on a table, in still appreciable shape, a being which walked in the sunshine, which lived and loved 500 years before Moses, 2,000 years before Jesus Christ?’

A mummy unwrapping session in Cairo in 1886 – note the fashionable lady spectator

But if mummies had largely become objects of touristic enthusiasm or items to be plundered and carried back to Europe to be either unwrapped or displayed, what of the powder mummia? Did Europeans finally stop grinding up the ancient dead? Mummia did continue to have a function even though far fewer people swallowed it as a drug. To understand that purpose, we’ll need to look to the world of fine art.

Mummia as an Artists’ Pigment – the Burial of ‘Mummy Brown’ and Painting with Ground-up French Kings

For some time, European artists had been using a paint known as ‘mummy brown’ – a rich brown bituminous pigment. This paint – also called Egyptian brown and caput mortuum (dead man’s head) – seems to have been developed in the 16th or 17th century. It was made from myrrh, white pitch and – ground-up Ancient Egyptian mummies. As with medical mummia, however, high demand could result in less-than-authentic mummies being used. Sometimes the mummies of cats replaced those of humans; sometimes the bodies of recently deceased criminals and slaves found their way into the paint. On occasion, mummies from the Canary Islands substituted the Egyptian variety – the aboriginal people of the islands, the Guanche, had also embalmed their dead.

Tubes of mummy brown paint from Roberson’s of London. (Photo: Lulu_Geek)

Opinions about mummy brown differed. Some artists felt it had good transparency and was good for glazes, shadows, flesh tones and shading. It was said to ‘flow from the brush with delightful freedom and evenness’. The pigment, however, varied in quality, with the paint from some batches prone to cracking. As mummy brown contained ammonia and particles of fat, it could sully other colours. One critic complained that ‘these crumbled remains of dead bodies’ were ‘more or less liable to injure the colours with which they may be united’ before concluding there was ‘nothing to be gained by smearing our canvas with a part perhaps of the wife of Potiphar, that might not be as easily secured by materials less frail and of more sober character.’

Liberty Leading the People by Eugene Delacroix (1830) might well have been painted with mummy brown.

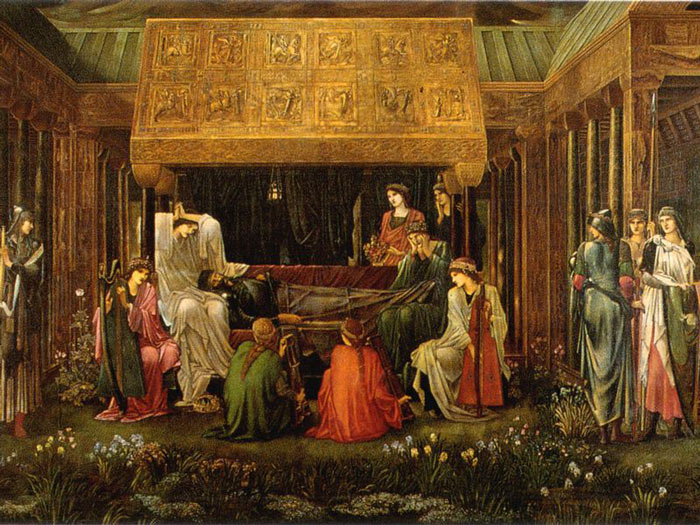

The variability in mummy brown’s composition makes it difficult to know which paintings it appears in, but mummy brown was fashionable from the mid-18th to the late-19th century. Delacroix is known to have used it, the British portraitist William Beechey had stocks of the substance, and it was used by the Anglo-Dutch painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema, a friend of the Pre-Raphaelites. One work that made much use of mummy brown was Interior of a Kitchen (1815) by the French painter Martin Drolling. Drolling’s mummy brown is rumoured to have come from an astonishing source. The Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis (now in a Paris suburb) also served as a royal necropolis and almost every French monarch from the 10th century onwards had been buried there. After the French Revolution, the government ordered the destruction of the royal sepulchres. The royal bodies – some of which were exceptionally well-preserved – were yanked from their tombs, hurled into pits and covered with quick lime. But some workmen, apparently, couldn’t resist grabbing ‘souvenirs’. These mementoes allegedly included jaws, sections of skulls, nails, moustaches, Henry III’s teeth, Phillipe Auguste’s hair and an entire arm of Catherine de Medici. Some of the royal remains are said to have ended up transformed into mummy brown and – according to legend – Drolling daubed this very paint onto his canvas.

Martin Drolling’s Interior of a Kitchen (1815) – was it painted with mummy brown made from the corpses of French monarchs?

Mummy brown was popular with the Pre-Raphaelites, especially with Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98). It seems Burne-Jones was, however, using the pigment while unaware of its gruesome origins. According to a book by his widow Georgina, Burne-Jones had invited Alma-Tadema for Sunday lunch with his family. After the meal, the two men discussed colours. Georgina wrote, ‘Mr Tadema startled us by saying that he had lately been invited to go and see a mummy that was in his colourman’s workshop before it was ground down into paint.’ Burne-Jones scoffed at the notion that the pigment ‘had anything to do with a mummy’ and ‘said the name must only be borrowed to describe a particular shade of brown.’ When, Georgina maintains, Tadema managed to convince Burne-Jones the paint really was made from mummies, Burne-Jones ‘left us at once, hastened to the studio, and returning with the only tube he had, insisted on our giving it a decent burial there and then. So a hole was bored in the green grass at our feet, and we all watched it put safely in, and the spot was marked by one of the girls planting a daisy root above it.’

The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon by Edward Burne-Jones (1880-98), which was probably painted using mummy brown.

Another person present at the lunch was Georgina’s nephew, a young Rudyard Kipling. Kipling recalled Burne-Jones descending ‘in broad daylight with a tube of mummy brown in his hand, saying that he had discovered it was made of dead Pharaohs and we must bury it accordingly. So we all went out and helped – according to the rites of Mizraim and Memphis, I hope – and to this day I could drive a spade to within a foot of where that tube lies.’

The use of the pigment declined in the early 20th century as more artists – like Burne-Jones – learned of its unsavoury composition and respect for the historical, archaeological and cultural value of mummies increased. Mummy brown was, however, available to those who really wanted it for a surprisingly long time. This may have been due to the fact that large quantities of paint could be produced from just a few mummies. In 1915, one colourman stated that a single mummy had kept his customers supplied with the pigment for two decades. The famous colour-makers Roberson’s of London stocked the paint until the early 1960s though demand by that time was very low. In 1963, the firm had to remove the pigment from its catalogue because it had finally run out of mummies. ‘We might have a few odd limbs lying about somewhere,’ the director said, ‘but not enough to make any more paint. We sold our last complete mummy some years ago for, I think, £3. Perhaps we shouldn’t have. We certainly can’t get any more.’ Though you can purchase a modern pigment called mummy brown, it’s made of kaolin, quartz, goethite and hematite – with no taint of desiccated cadavers.

A modern version of mummy brown – entirely free from ancient mummies. (Photo: news.artnet)

But what of the medical use of mummia? By the early 1700s, the drug’s popularity was in sharp decline. The English medical author John Quincy wrote in 1718 that although mummia was listed in medical catalogues, ‘it is quite out of prescription’. So does this mean that the mania for mummia, that the belief that ingesting ancient corpses can boost our health, belongs solely to a superstitious past? This doesn’t entirely appear to be the case. The substance could be found as late as 1924 on the price list of the large pharmaceutical company Merck & Co. Even more incredibly, in 1973 a shop in New York that sold ‘witches’ supplies’ was offering what it claimed was powered mummy. Although Ancient Egypt’s magic and mystique seem destined to haunt the Western consciousness for some time to come, let’s hope our obsession with this culture will never again focus on edible artefacts.

(This article’s main image is a photo from the excavation of King Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1923. The king’s mummy wasn’t ground up to make mummia or mummy brown.)

What a fascinating article – I was aware of mummy unwrapping parties but not the mummies being put to many dubious uses. It is really creepy to think of famous paintings being created with ‘mummy brown’. I really enjoyed but then I’ve always had a morbid fascination with Egypt and it’s afterlife.

Hi Carol, many thanks for reading. The range of dubious uses mummies have been put to is incredible – from ‘medicine’ to paint to tourist attractions to party pieces. Perhaps it does show an enduring fascination with Ancient Egypt over the centuries.

Awesome and interesting article. I had some idea of the use of mummies as medicine but what I have just readed ( and enjoyed) is far more than I could have expected. Congrats!

Wow; truth being far stranger than fiction! Such a lack of disrespect for the dead too, shameful. Great article, like the rest of the blog it seems really well researched and informative, no supposition; fab!

Many thanks, Pandrosion.