Christmas is not a time we associate with weird customs. Admittedly, the idea of a chubby old man in a red suit coming down our chimney at night might seem bizarre. The practice of putting a severed pine tree in our living room and festooning it with lights could also be viewed as somewhat strange. But these things have become so enmeshed in Western culture we don’t see them as odd.

But what if I were to tell you that some Welsh villagers celebrate Christmas by parading a real horse’s skull through the streets, a skull that lobs insulting rhymes at householders? What if I informed you that the festive season was once enlivened by plays enacting ritual murders or by the clashing of sparking swords that were then held up in a knotted formation ‘in homage to the sun’? Or that the arrival of Christmas has been marked by house visitors dressed as the Devil, by choirboys masquerading as bishops and clergymen disguising themselves as choirboys, by animal skulls buried in back gardens or hidden in cupboards under stairs, and by songs celebrating the dismemberment of monstrous rams?

Christmas, despite the glittery commercialisation of the festival, can be a strange and spooky time. So let’s go for a wander through Britain’s towns and villages, through its draughty cathedrals and warm pubs, and through its present and past to see what we can discover about the bizarre ways the festive season has been made both more fun and more sinister.

Number One: Mari Lwyd – the White-Sheeted, Horse-Skulled Entity that Welcomes the Welsh Christmas

If you happened to be in certain parts of Wales around Christmas, you might be shocked to see a disturbing figure processing along the streets after dark. This figure has a bare horse’s skull for a head, a skull sometimes decorated with ribbons and often with baubles or lights for eyes. The head might twitch spookily around; its jaws might open and snap with an eerie clacking. The ‘neck and body’ of this creature are draped in a white sheet. Towering above the people thronging around it, this character makes its slow and ominous way between houses and pubs. Deeply sinister yet robustly carnivalesque, the ‘horse’ might pause to peer down at people, its eyes equally unnerving whether they’re plugged with glimmering orbs or simply black pits.

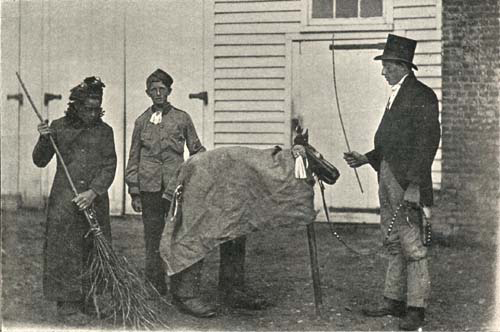

The Mari Lwyd, the skull-headed hobby horse of Welsh Christmas custom. (Photo: R. Fiend)

The beast – known as the Mari Lwyd – is accompanied by human figures. There’s usually a smartly dressed ‘leader’ or ‘sergeant’ carrying a stick or whip and two brightly attired individuals – both men – playing Punch and Judy, with Punch clutching a fire iron and Judy a broom. There are ‘merry men’ making music – their swirling tunes issuing hypnotically from accordions or violins – all decked out in colourful clothes enlivened with ribbons, rosettes and sashes. (The skull itself tops a long pole, held by someone hiding inside the sheet, who may also operate the jaw-clacking mechanism.)

This strange procession might now stop in front of a house. The Mari Lwyd’s party sing a verse asking for admittance. The song, depending on the neighbourhood, could be in Welsh or English and might go like this:

‘Well here we come

Innocent friends

To ask leave, to ask leave

To ask leave to sing.’

A verse is then sung back by the house’s inhabitants. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they don’t want a skull-headed horse parading through their dwelling so they offer excuses about why they can’t let the Mari Lwyd in. A verse is sung in response by the Mari Lwyd’s party pleading to be allowed to enter and the house’s residents might reply with another verse putting the creature off. Things can get quite clever, with exchanges of poetry, jokes and good-natured insults, as well as increasingly sophisticated reasons for why the Mari Lwyd shouldn’t pass the threshold. Eventually, the householders run out of excuses so they have to permit the horse and its companions entry. One record of this swapping of verses is as follows:

‘Open your doors,

Let us come and play,

It’s cold here in the snow,

At Christmastide’

‘Go away you old monkeys,

Your breath stinks,

And stop blathering.

It’s Christmastide.’

‘Our mare is very pretty,

Let her come and play,

Her hair is full of ribbons

At Christmastide.’

‘Instead of freezing,

We’ll lead the Mari,

Inside to amuse us.

Tonight is Christmastide.’

Once the party are within the house, the ‘fun’ really begins. The Mari Lwyd gambols around, snapping its bony jaws. The horse attempts to steal things; it chases and frightens children and even adults while the ‘leader’ makes a show of trying to restrain it. The merry men play music to entertain the householders, who are obliged to give the strange ensemble food and ale. The Punch character might keep the music’s rhythm by rapping the ground or tapping doors with his poker. Judy might go on a manic cleaning spree, brushing not only floors but also walls and windows. The house’s residents, however, would have made Punch promise not to touch the fireplace before entering – otherwise he’d rake the fire out. After eating, drinking and creating all kinds of mayhem, the group leave. The Mari Lwyd continues its eerie procession along the street, looking for another house to call at. Despite the chaos the horse causes, it’s thought to bring luck to any dwelling it enters.

Three Mari Lwyds celebrate the Christmas season. (Photo: pbs.twimg)

The Mari Lwyd can make its rounds at any time from dusk until late at night. The skeletal horse can appear on any day from shortly before Christmas till after Twelfth Night (5th January) and in some districts the Mari Lwyd may be out on multiple evenings. Records show that customs have varied between places. Different characters can appear in the horse’s entourage, including – in modern times – jesters, people in ‘traditional’ Welsh costume, revellers dressed like morris dancers and mummers, and even green men. In some settlements, the skull is made of wood or paper. At one place in Gower, a real skull was kept buried throughout the year before being unearthed as Christmas approached. In some localities, the Mari Lwyd was allowed in after only one verse whilst in others lengthy banter always took place.

When considering what could account for this bizarre spectacle, many unsurprisingly point towards the pagan past. ‘Mari Lwyd’ might mean ‘grey mare’ and in Celtic Britain horses symbolised fertility and power. People believed that certain animals had the ability to cross between this world and the otherworld, especially at ‘turning points’ of the year like midwinter and Halloween when the boundaries between realms were thin. In Welsh tradition, such creatures were usually white or grey. The Mabinogion – a medieval Welsh epic based on earlier mythology – features Rhiannon, a queen from the otherworld who rides a majestic white horse. Rhiannon may be based on memories of a Celtic horse goddess. The hounds of Annwn, the Lord of the Underworld, which sometimes pass over to hunt in this realm, are also white. The hounds tend to be sighted in midwinter and can be harbingers of death.

Might the white, skull-headed yet strangely energetic horse represent not only the year ‘dying’ around Christmastime but also its renewal with the return of life from the underworld? Could it symbolise the promise of life coming back in spring after nature’s ‘death’ in winter? The verbal jousting of the Mari Lwyd tradition may also have profound roots in Welsh culture. The Mabinogion features combats of wits and wordplay – battles which may take place between unequal opponents, one of whom may be fortified by supernatural powers.

While themes from Welsh myth might linger in the Mari Lwyd custom, the tradition’s claims to a pagan origin have been challenged. Some suspect the ritual is of Christian ancestry, arguing the ‘Mari’ in the horse’s name refers to ‘Mary’ rather than ‘mare’. A piece of Christian folklore asserts that when the Holy Family arrived at the stable, a pregnant mare was expelled from it. The mare spent dark days roving the land, searching for somewhere to birth her foal. Parts of the Mari Lwyd tradition may have come from Christian mystery plays, with characters like the sergeant and the merry men drawn from such performances. Some suggest the Mari Lwyd might represent the donkey on which Mary rode.

The Mari Lwyd custom is probably related to other ‘hooded animal’ traditions, in which a hobby horse or animal skull is paraded through the streets and taken to visit houses. Such ceremonies – which include the Hoodening in Kent and Old Tup in South Yorkshire and Derbyshire – may have started as a way for poor people to earn food and money during the harsh winter months. They tried to acquire these necessities by providing amusement, though this amusement was backed up with a certain degree of menace – symbolised by the animal’s skull being carried to your door.

The Welsh Christmas tradition of the Mari Lwyd. (Photo: Patheos)

An argument against the ‘pagan origins’ theory is the apparent age of the tradition. The earliest-known reference to the Mari Lwyd is in J. Evans’s A Tour through Part of North Wales , in the Year 1798 and at Other Times (1800). In this work, Evans describes a man on New Year’s Day ‘dressed in blankets, with a factitious head like a horse’ knocking for admittance to a house then running ‘about the room with an uncommon frightful noise, which the company quit in real or pretended fright.’ Evans gives a more in-depth depiction of the custom in his 1804 book Letters Written During a Tour Though South Wales, in the Year 1803, and at Other Times. (The Mari Lwyd tradition is much more associated with South than with North or Mid-Wales). The next known mention of the Mari Lwyd is from 1819.

While the Mari Lwyd no doubt goes back earlier than Evans’s account, there’s a lack of medieval references to hobby horse or hooded animal type customs. Some think they may have emerged from a documented craze for hobby horses in the elite of British society in the 16th and 17th centuries, an enthusiasm that then spread to other social classes. The Punch and Judy characters in the Mari Lwyd’s entourage probably came from the puppet theatres popular in the 18th century, which in turn derived from the 16th-century Italian commedia dell’arte.

A Mari Lwyd photographed between 1904 and 1910 in Llangynwyd

Whatever its origins and whatever its age, the Mari Lwyd tradition was at one point in danger of dying out. It was weakened by attacks from fiery Methodist and Baptist preachers in the 1800s. In 1852, the Reverend William Roberts – a Baptist minister at Blaenau Gwent – condemned the Mari Lwyd as ‘a mixture of old Popish and Pagan ceremonies … I wish of this folly, and all similar follies, that they find no place anywhere apart from the museum of the historian and antiquary.’ Roberts attacked the horse as ‘sinful’ in his book The Religion of the Dark Ages but in this work he also took it upon himself to transcribe 20 verses of Mari Lwyd songs. The Reverend would probably be horrified to know that his book proved a useful resource to later folklorists determined to revive the custom. In addition to the disapproval of the religious, the Mari Lwyd ritual seems to have been eroded by industrialisation and urbanisation, as the springing up of pubs and clubs to serve industrial communities lessened the need to celebrate Christmas with house visiting customs. The Mari Lwyd ceremony also seems to have got a bad reputation due to the drunkenness and vandalism of some participants.

The tradition almost disappeared in the early-to-mid-1900s. But – appropriately for a creature that represents life’s resilience in the harshest season – the Mari Lwyd refused to expire. There were occasional sightings of the bony horse – on Christmas Eve in 1934 in the Mumbles and in 1967 at the Barley Mow Inn at Graig Penllyn near Cowbridge, where a man had apparently spent 60 years striving to keep the custom alive. One man, whose father had been in charge of the Mari at Llantrisant, recalled discovering the redundant skull in a cupboard under the stairs in the 1930s – a somewhat dark variant on a child stumbling across the Christmas decorations out of season! Cautious revivals – mostly by folklorists – began in the 1970s and gathered force in the 1980s. Today the Mari Lwyd can be seen patrolling winter streets throughout Wales and its popularity is growing. Perhaps some view this macabre but joyful Welsh tradition as a balance to the sentimental yet commercialised global American Christmas.

A Mari Lwyd, photographed between 1910 and 1914, in Llangynwyd

In the sombre days of the Mari Lwyd’s decline, the poet Vernon Watkins heard about a then-rare Mari ritual in a village north of Cardiff on the radio. This inspired his 1941 poem The Ballad of the Mari Lwyd: ‘The living are defended by the rich warmth of the flames which keeps that loneliness out. Terrified, they hear the dead tapping at the panes; then they rise up, armed with the warmth of firelight.’

The (Welsh) former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams has described Watkins’ effort as ‘one of the outstanding poems of the century’ which ‘draws together the folk-ritual of the New Year, the Christian Eucharist, the uneasy frontier between living and dead, so as to present a model of what poetry itself is – frontier work between death and life, old year and new.’

Number Two: Poor Old Hoss – a Weird Christmas Custom in Richmond, North Yorkshire

The strange Christmas Eve custom of the Poor Old Hoss, in Richmond, North Yorkshire. (Image: Around and About Yorkshire)

A strange Christmas tradition with similarities to the Mari Lwyd takes place in Richmond, North Yorkshire. On Christmas Eve – but during the daytime rather than at night – a grotesque creature is led around the town’s cobbled marketplace. Known as the Poor Old Hoss, this tall, black-robed character boasts a horse’s skull, though it’s covered in black fabric rather than being bare. The Hoss (or horse) is accompanied by huntsmen, clutching riding crops, their hats holly-crowned. With the Hoss, they call in at shops and pubs. The Hoss – like the Mari Lwyd – acts up, entertaining and terrorising bystanders, and trying to steal sandwiches and even drink coffee in the cafés. To see the Hoss, though, or have him enter your premises is considered good luck. The custom, however, has its darker edge. An accordion player tags along with the huntsmen and they sing a dirge about the Poor Old Hoss. The first verse goes:

‘You gentlemen and sportsmen,

and men of courage bold,

All you that’s got a good horse,

Take care of him when he’s old

Then put him in your stable,

And keep him there so warm,

Give him good corn and hay,

Pray let him take no harm,

Poor old horse! Poor old horse!’

The ‘poor old horse’ refrain ends each verse, at which the horse supplies percussion by snapping his jaws. The song goes on to lament the sufferings of the ageing horse, decrying the fact that his ‘pretty little shoulders that were once plump and round’ are ‘decayed and rotten, I’m afraid they’re not so sound’. We learn the horse’s once ‘nimble little legs that have run many miles, over hedges, over ditches, over valleys, gates and stiles’ are in a similar sad state and that – despite the horse once possessing a ‘tail and mane of length’ and ‘a body that did shine’ – he is ‘now growing old.’ The horse, however, is still lively enough to perform ‘actions’ to the words, nuzzling up to the huntsmen and vigorously imitating the leaping of hedges or chomping of hay. The beast nevertheless complains of how its enfeebled powers have led to mistreatment from its master:

‘I used to be kept

On the best corn and hay

That in fields could be grown,

Or in any meadows gay;

But now alas, it’s not so,

There’s no such food at all!

I’m forced to nip the short grass,

that grows beneath your wall.

Poor old horse! Poor old horse!

I used to be kept up,

All in a stable warm,

To keep my tender body.

From any cold or harm;

But now I’m turned out,

In the open fields to go,

To face all kinds of weather,

The wind, cold, frost and snow.

Poor old horse! Poor old horse!’

Eventually, the sorrowful horse has to conclude:

‘My hide unto the huntsmen,

So freely I would give,

My body to the hounds,

For I’d rather die than live:

So shoot him, whip him, strip him,

To the huntsmen let him go;

For he’s neither fit to ride upon,

Nor in any team to draw.

Poor old horse! You must die!’

At this point, the huntsmen surround the Hoss and start hitting him with their crops. Under this bombardment of blows, the horse sinks to the ground and lies upon the pavement as if dead. Then, however, a man blows a blast on a hunting horn and the horse clambers back up to the applause of the huntsmen and spectators, apparently revived and cured of all the ailments mentioned in the song. The horse and its entourage then move on to another part of the marketplace, where they repeat the performance.

People in Richmond will tell you this custom has been handed down from the remotest antiquity and is pagan in origin. It’s easy to see why they might think so. The horse’s apparent death could represent the dying of the old year and the barrenness of nature in midwinter. The joyful resurrection of the Hoss, however, could herald the new year coming and the approach of spring. Like the Mari Lwyd, the Poor Old Hoss brings luck, perhaps representing the fertility this talisman of renewal might bestow. There are also, perhaps, echoes of sacrifice customs with the horse seemingly willing to die. The folklorist Robert Bell linked Richmond’s humble Hoss to Sleipnir, the lightening fast steed of Odin, king of the Norse gods. Though the elderly Hoss would seem a poor representative of a horse that could fly through the air and ‘ride sea and sky’, Odin’s mount did travel to the land of the dead, which might suggest a link with the Hoss’s resurrection.

The evidence, however, indicates the Hoss ritual isn’t so antique. The song’s first recorded in Bell’s 1857 book Ancient Poems, Ballads and Songs of the Peasantry of England in a section entitled The Mummers’ Song; or the Poor Old Horse, As Sung by the Mummers in the Neighbourhood of Richmond, Yorkshire, at the merrie time of Christmas. The custom does probably stretch back earlier – some, for instance, say there were once 20 verses of the song: many were presumably lost over the years as Bell only documented six. There’s also apparently a mention of a Richmond custom similar to the Poor Old Hoss from the 1600s. The lack of earlier records, however, likely suggests the tradition doesn’t go back much further than this. As with the Mari Lwyd, the Poor Old Hoss might have originated in an early modern hobby horse craze or been a way for the poor to earn food, money or refreshment around Christmas.

And as with the Mari, the Poor Old Hoss custom seems to have undergone its own death and revival. The tradition lapsed in World War II and after hostilities had ended, a new skull was ordered from a slaughterhouse. Julia Smith’s Fairs, Feasts and Frolics (1989) states that the skull was fitted ‘with eyes of black glass, painstakingly chipped from a bottle of old wine, rounded on the inside’ and ‘wired together so that the jaws could be opened and closed while the inside of the mouth was lined with red plush velvet. The whole skull was covered with material to represent the skin … the horse … was adorned with artificial roses and poinsettias.’

Alas, at least according to some, this spanking new skull couldn’t compete with a very modern enemy – the television. (Perhaps at this time the Poor Old Hoss was more of a house visiting custom.) The teams hefting the Hoss around soon felt they were intruding on people intent on paying attention to the flickering box in their living rooms. The custom appears to have died out in the 1950s, with the skull being – ceremonially? – buried in a chief mummer’s back garden. The tradition, however, seems to have revived in the early 1980s and must have been going strong by the mid-nineties when it got a mention in Quentin Cooper’s and Paul Sullivan’s 1996 book Maypoles, Martyrs and Mayhem. The Hoss is viewed as a vital component of Christmas in Richmond today.

A number of other strange Christmas folkloric customs bear similarities to the Mari Lwyd and Poor Old Hoss. In and around Sheffield, a tradition was based on a folksong called The Old Tup or Derby Ram. This song celebrated a beast so enormous that its horns reached the moon and its hooves each covered one acre. Parties – sometimes made up of children, sometimes of grown men – called at houses. In the ceremony’s most simple form, a person – covered by a sheet – brandished a pair of sheep’s or goat’s horns, but some versions of the ritual employed elaborate wooden frames or a full sheep’s head, sometimes carved from wood and sometimes real. In the latter case, complaints were often made about the smell. The characters in the ram’s entourage could include a knife-wielding butcher, an old man and old woman (played by a man dressed up who sometimes clutched a broom), and demonic figures with names like Beelzebub and Little Devil Doubt. The participants would sing the song while the ram capered around before they seized and pretended to kill him. The butcher usually performed the honours, with another character catching the ‘blood’ in a bowl. The song next described how the parts of the ram were transformed into useful items:

‘And all the boys in Derby,

Came running for his eyes

To make a pair of footballs

For they were football size.’

The ram would then get back up and the party would leave. Records show the Old Tup tradition was still vigorous in the 1970s, with 41 troupes being recorded in north-east Derbyshire alone. The custom is still followed today.

An individual dressed up as Old Tup in Handsworth, Sheffield, from a book published in 1907

Sheffield – and nearby parts of Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire – also had a Christmas ‘Old Horse’ tradition. The horse, accompanied by one or two attendants, including a blacksmith, visited houses. Once inside, the blacksmith would try to shoe the horse, who’d resist and gambol about while the party sang a song. At a certain point, the horse would ‘die’ and be revived. After the performance, the householders provided their visitors with food and drink. This custom seems to have lasted from the 1840s till the mid-1900s.

A team with a Hooden Horse, in Sarre, Kent, 1905

In eastern Kent, a number of villages marked Christmas with an ‘animal disguise’ tradition known as the ‘Hooden Horse’. A wooden horse’s head was festooned with ribbons, rosettes and brasses and mounted on a pole, supported by a man under a dark cloth. The horse’s ‘team’ might consist of a jockey, a broom-clasping woman called Molly (played by a man), a groom and a musician. This ensemble would tour their neighbourhood visiting houses on Christmas Eve. They’d entertain residents by having the horse play up and the jockey try to ride him and would be given food, money and drink before moving on. By the turn of the 20th century, over 30 local versions of the ‘Hooden Horse’ had been recorded, but by 1910 the tradition had all but died out. A post-War revival, however, has meant that the Hooden Horse is now often a feature of Kent Christmases and other festive occasions, generally appearing in morris dances and mummers plays.

Hoodeners in Walmer, Kent, in 1907

Number Three: the Strange Christmas Custom of Mummers’ Plays

‘In comes I, Old Father Christmas

Am I welcome or am I not?

I hope Old Father Christmas

Will never be forgot.’

Another peculiar house visiting Christmas tradition was that of the mummers’ plays. Teams in bizarre costumes would tour the countryside calling at houses and pubs. They’d put on a mock-heroic performance then finish up with a few lustily delivered songs. Large country houses seem to have been especially popular venues, presumably because the mummers could expect a more generous payment at such places. Indeed, like the traditions mentioned above, mumming was a way for working-class folks to earn extra cash. Labouring men could make the equivalent of two weeks’ wages from mumming and some teams would walk more than thirty miles a day to cram in as many performances as possible.

A mummers’ play as illustrated by Robert Seymour in 1836. Though a dragon can be seen, they weren’t common in such performances despite the presence of St George.

Though mummers performed at other holidays – including ‘turning points’ of the year such as Easter and Halloween – they were especially associated with the Christmas period. The play put on around Christmas involved a mock-heroic combat. After an introduction was declaimed by a character known as the ‘presenter’ (often Father Christmas), a knight would appear and – striding arrogantly around – make a boastful speech about his martial skills. The knight would challenge anyone who dared to disagree to a contest of arms and another knight would invariably pop up and offer to engage him in a sword fight. This exchange, delivered in rhyming couplets, might sound like this:

‘In comes I, King George

That man of courage bold

If his blood be hot

I’ll quickly fetch it cold …

If you don’t believe the words I say

Step in Bold Slasher and clear the way.’

The knights would fight, clashing their fake swords, and one would be wounded or killed. In some mummers’ plays, another knight might then appear and also end up injured or dead and in some even a third would step forward to meet the same fate. Another character – usually the presenter – would mourn the brave knight’s death and cry out for a doctor. A ‘doctor’ would bustle in, making comic boasts:

‘In comes I Doctor Brown

The best old doctor in this town

I can cure the ips, the pips, the palsy and the gout

The pains within and the pains without

If a man has nineteen devils in his body

I can fetch out twenty.’

Despite his ridiculous claims, the doctor would turn out to be a skilled practitioner. He’d kneel down over the slain knight and – usually with some drops from a bottle – manage to revive and resurrect him. Following this miraculous feat, a number of extra characters might come in and make speeches, one of whom would inevitably remind the audience to compensate the troupe with food, money and drink. These supernumerary figures tended to represent the greatest diversity between how the play was acted among different teams and in different regions. The supernumeraries might include a fool, devils – called Beelzebub or Little Devil Doubt – and characters with names like Johnny Jack and Billy Sweep. Often – as in the customs above – there’d be a cross-dressing man, called Molly or Betsy, usually armed with a broom. A supernumerary’s speech could go:

‘In comes I Beelzebub

Over my shoulder I carry me club

In my hand a dripping pan

Don’t you think I’m a fine old man?’

As for the main characters, one knight would be Saint or King George. His challenger might be a Turkish knight or a soldier with a name like ‘Bold Slasher’. The doctor might be called Doctor Dodd, but Doctor Brown seems to have been more common, presumably because it rhymed with ‘town’. The Father Christmas wouldn’t have been like the modern Santa Claus. The original English Old Father Christmas evolved from a character that developed around the time of the Civil War (1642-51) – a figure from pamphlets who resisted Puritan attempts to outlaw Christmas and urged people to glug their ale and enjoy seasonal good cheer.

A traditional mummers’ play might seem curious to a modern audience. Lines were delivered woodenly in a declamatory fashion with little attempt to portray ‘character’ and the actors’ movements were stiff and stylised. There was no pantomime cheering or booing or attempts to ham things up. While the plays contained comic moments, other parts were apparently taken seriously, with the mix of amusement and mournfulness perhaps similar to that found in the animal customs above. Costumes varied by region. In southern England, mummers often wore bizarre clothes with long strips of wallpaper or rags sewn on and tall hats festooned with rosettes, tinsel and streamers. In other areas, mummers might wear patched clothing decorated with ribbons and tassels, with many troupes blacking their faces as a form of disguise. As the 20th century rolled around, there was a move towards the actors dressing more in character – with Father Christmas robed and white-bearded, the doctor in a frock coat and top hat, and the knights in military attire.

Despite the lack of theatricality, the experience of having mummers call at your door and emerge strangely clad out of the night to give their robust performance could be a profound and even frightening event. The Wind in the Willows author Kenneth Grahame recalled a troupe visiting his childhood home in the 1860s:

‘Twelfth Night had come and gone, and life next morning seemed a trifle flat and purposeless. But yester-eve and the mummers were here! They had come striding into the old kitchen, powdering the redbrick floor with snow from their barbaric bedizenments and stamping, and crossing, and declaiming, till all was whirl and riot and shout. Harold was frankly afraid; unabashed, he buried himself in the cook’s ample bosom. Edward feigned a manly superiority to illusion, and greeted these awful apparitions familiarly … As for me, I was too big to run, too rapt to resist the magic and surprise. Whence came these outlanders, breaking in on us with song and ordered masque and a terrible clashing of wooden swords?’

Like the other customs mentioned in this article, there might seem a certain paganism to mummers’ plays. At the darkest point of the year, when nature appears dead and the sun is at his weakest, a play is staged by weirdly garbed performers in which a man is killed and then – after much lamentation – miraculously revived. The sun will likewise overcome his apparent death to strengthen in the sky and bring back the spring. While such concerns with birth, rebirth, resurrection and nature’s barrenness have no doubt weighed on people’s minds in mid-winter throughout both pagan and Christian epochs, mummers’ plays themselves cannot be traced back to ancient times. Though the term ‘mumming’ was used in the Middle Ages, it referred to a variety of revels, games and mask-wearing traditions and there are no records of the type of play described here before the mid-18th century. The plays’ origins are, nonetheless, something of a mystery, but it’s possible they derived from mock-heroic puppet plays or the antics of troupes of travelling actors. Chapbooks have been found containing texts for mumming performances and – sold in local shops or by roving peddlers – might have helped spread the tradition.

A modern mummers’ play performed on Boxing Day 2015 in St Albans. (Photo: Michael Maggs)

As with other Christmas customs, mummers’ plays have undergone their own cycle of decay and renewal. After fading away and almost dying out in the interwar years, the plays were revived by folklore enthusiasts in the 1960s. Purists, however, criticise the modern plays for straying too far from their earnest and charmingly wooden predecessors. Some claim they’re overly influenced by pantomimes, amateur dramatics and melodrama and that they’ve merged too much with what was once a mostly separate tradition, that of morris dancing.

Number Four: the Sword Dance – a Knot Raised ‘in Homage to the Sun’ and a Decapitation

Another Christmas house visiting custom – sometimes linked to mumming – was the sword dance. Especially common in Northumberland, County Durham and Yorkshire, this practice involved a group of men armed with ‘swords’ made of wood or pliable metal. The men danced in circular patterns before – at the end – interlacing their weapons to form a ‘lock’ or ‘rose’. One of the dancers then raised this ‘knot’ in triumph towards the sky.

The knot of swords is held up to the sky prior to being placed around a dancer’s neck, in Grenoside, Yorkshire, on Boxing Day, 2005. (Photo: Gerry Bates)

The sword dance often began with a ‘calling on song’ to introduce the dancers and the troupe could include additional characters such as a fool and a cross-dressing man named Bessie or Betsy. These supernumeraries often didn’t participate in the dance and may have been leftovers from a play once performed as part of the sword dance custom. Some sword dances boasted an additional – some might say sinister – feature. The blades could be interlocked around somebody’s neck – then swiftly withdrawn in a mock decapitation ritual.

A lady from Northumberland recalled her experience of the sword dance for a book published in 1929: ‘Sword dancers came at the New Year, in the dark, and danced the sword dance in the backyard by the light of lanterns, all dressed up – there was old Betty, and Nelson, and a doctor, and after they’d finished the dance one held up all the swords. They came from Boghall. Yes, miners and the lads about.’

The sword dance contains powerful symbolism – the knot being held up like a sun, the decapitation that for all the world seems like a human sacrifice. Then there’s the phallic nature of the swords themselves. Whether such things are pagan remnants, however, isn’t clear. References to sword dances can be found across Europe from the Middle Ages onwards while in Britain the dance’s popularity seems to have surged from the mid-1700s. Though nowadays sword dancers don’t tend to call at houses, teams can still be found performing across England’s north east. Longer swords are preferred in Yorkshire while the swift dances of Durham and Northumberland use shorter swords called ‘rappers’.

Number Five: the Boy Bishop – an Odd Christmas Tradition of Role Reversal

In Salisbury Cathedral an extremely strange tomb can be found. This miniature grave bears a representation of a diminutive bishop. Though dressed in robes and mitre, clutching a crozier and appearing full of all the ecclesiastical dignity of his office, the effigy on the grave is only the size of a young boy. This effigy is said to cover the resting place of a ‘boy bishop’ who – having died in office – was given all the funerary honours an adult bishop would receive. But what was a boy bishop and what did this weird tradition have to do with Christmas?

The boy bishop custom – which, as the name implies, involved a boy stepping into a bishop’s role and assuming his duties – was once a popular and widespread Christmas practice. A cathedral choirboy would be chosen for this honour and his bishop would gracefully step down and let his young replacement reign in his stead over the Christmas period.

The boy bishop began his rule on St Nicholas’s Day (6th December) and reigned until the Feast of Holy Innocents (December 28th). The boy would be inaugurated in a ceremony on the 6th. Wearing full bishop’s regalia and attended by his friends dressed as priests, the boy would approach the adult bishop’s throne. Before the singing of the Magnificat (a song based on words spoken by Mary in the Gospel of Luke), the bishop would descend from his chair and give his youthful successor his blessing. Then the choir would blast the song out and upon the words ‘He hath put down the mighty from their seats’, the boy would seat himself upon the bishop’s throne and proceed to bless the congregation with movements of his pastoral staff.

Once inaugurated, the boy bishop would perform all the duties of a real bishop, except for saying mass. He’d preach sermons he’d written himself and – with his retinue of young priests – would tour the city, blessing the populace who’d flocked to see him while singing songs and handing out gifts and sweets. In York, the boy bishop and his followers even undertook a tour on horseback of outlying villages. Boy bishops had the power to declare holidays and to decide what any money collected from the laity would be spent on. Adult clergymen sometimes joined in this festive role reversal, dressing up as choristers and altar boys and serving their youthful – though temporary – masters. During a lavish service on Holy Innocents’ Day, the boy bishop would hand power back to his adult predecessor and normality would resume.

A 19th-century depiction of a boy bishop, with his entourage of young priests

The tradition could vary between places, with the boy bishop allowed more freedom in some cathedrals than in others. In some localities the custom appears to have been more serious; in others the focus was on high jinks and the burlesque. Though enormously popular in medieval times, the boy bishop custom was always controversial because of its apparent mockery of the clergy. When Henry VIII made himself head of the Church of England in 1531, he decided the custom was too much of an affront to his dignity and banned it. It was restored by his Catholic daughter Mary but again stamped out when Queen Elizabeth took the throne and once more positioned the monarchy at the Church’s head. It seems that as time had gone on, the tradition had become more raucous and slapstick, with the adult ‘choristers’ notorious for rudely disrupting services. More sober and earnest members of the community appear to have been glad to see the boy bishop go. On the Continent, the custom lingered on, in parts of Germany until almost the 1800s.

Like many Christmas customs, however, the boy bishop tradition had both its comedic and solemn side. Biblical justification was found for it in Christ’s attitude towards children. In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus invited a child into the midst of his disciples and told them, ‘Unless you change and become like the little children, you will never enter the Kingdom of Heaven. Therefore, whoever humbles himself like a little child is the greatest in the Kingdom of Heaven.’ So the boy bishop tradition was both a celebration of the innocence of children and a reminder to the adult clergy not to become puffed up with pride. The dates when the boy’s reign began and ended are also linked to childhood. St Nicholas, the patron saint of children, was one of the figures who inspired the modern Santa Claus. Holy Innocents’ Day commemorated the children massacred by the wicked King Herod in his attempts to murder the infant Christ. The boy bishop ceremonies also enabled youngsters to learn about the rites and procedures of the Church.

But if we step outside the imposing and austere cathedral, we might see links between the boy bishop and more earthy Christmas customs. With the boy bishop, there’s obviously an element of role reversal going on, a little like all the cross-dressing in the rituals above. There seems to have been a notion that at ‘turning points of the year’ – like Christmas, Halloween and midsummer – ordinary rules, hierarchies and expectations were suspended or even overturned. Peasants believed that around Christmas they could hunt on the lord’s lands while ‘Lords’ or ‘Abbotts of Misrule’ were appointed as mock rulers to preside over rowdy Christmas feasts. The latter tradition seems to have stemmed from a custom among lower clergy known as the Feast of Fools. This feast would see the election of a mock bishop, archbishop or pope who’d preside over revels in which the higher clergy were ridiculed and church rituals parodied to the point of blasphemy.

Such role reversals at Christmas may possibly originate from Roman traditions like the Saturnalia and the Kalends of January. (Saturnalia occurred roughly around the Christmas period and the Kalends around New Year). The Saturnalia was marked by raucous merrymaking, the exchange of gifts and the suspension of social norms, with – for example – the usually illegal practice of gambling being permitted. It was also a time of equality between masters and slaves. Slaves could criticise their masters without threat of punishment and wear the clothes of freemen. Slaves and masters ate at the same table, with some sources suggesting the slaves were served first or that their masters even waited on them. A temporary ‘King of Saturn’ was elected to preside over the festivities. He gave absurd orders – such as ‘Sing naked!’ or ‘Throw him into water!’ – which had to be followed. The Kalends of January were also characterised by merrymaking and gift giving and by rowdy processions in which men cavorted through the streets dressed as animals or as women.

Despite the raucousness of ‘role reversal’ traditions it could be argued they had a conservative function. They were a ‘safety valve’ by which the tensions caused by ordinary social relations could be released. People could find relief by temporarily breaking out of rigid roles, with children and adults, men and women, and those of higher and lower ranks swapping places. The riotousness and absurdity of the customs also emphasised how ‘sane’ and ‘natural’ the regular order of things was.

It’s also been proposed that the appointment of mock lords, bishops and kings may have evolved from an ancient practice with a much darker purpose. In his massive study of myth, religion and folklore The Golden Bough (1890), George James Frazer suggested that a custom once existed by which a king would every few years be sacrificed to the gods to ensure the fertility of the land and prosperity of the people. Some kings, understandably less than enthusiastic about this tradition, instituted the practice of having a substitute – a kind of mock or joke king – replace them for a few days. Following a short period of enjoying luxuries and ruling over revels, this burlesque king would submit to death by sacrifice after which his predecessor would assume his old duties. Frazer’s ideas are out of fashion today, but he did manage to find a reference to the sacrifice of a King of Saturn carried out by soldiers on the Roman Empire’s fringes. The Empire had banned human sacrifice as an uncivilised practice, but in this outpost on the Danube older traditions had prevailed.

All this has strayed a long way from a tombstone effigy in Salisbury Cathedral, but the fact it’s still known as a boy bishop’s grave marker may indicate the hold over people the boy bishop tradition once had. Ironically, though, the tomb may not be a boy bishop’s at all. The monument might mark the resting place of the heart or viscera of the very-much-grown-up Bishop Richard Poore, the founder of Salisbury Cathedral, with the tomb’s size explained by the fact it only holds these organs. Poore, however, was famous for his concern for children. He funded the education of poor boys and made his clergy preach that children shouldn’t be left alone in any house containing fire or water.

The ‘boy bishop’ tomb in Salisbury Cathedral – a remnant of a strange Christmas custom? (Photo: Ealdgyth)

Like many other Christmas customs, the boy bishop ceremony has been resurrected, rising from the grave it was laid in centuries ago. Some cathedrals revived the tradition in the late 20th century though the modern versions are far less elaborate than their medieval forebears. They usually involve just one service on St Nicholas’s Day or on a Sunday close to it. At Salisbury and Hereford Cathedrals, for instance, the ‘boy bishop’ – draped in all the splendour of his robes – preaches a sermon he’s written himself, leads prayers, asks for God’s blessing on the people and gets to keep the money from the collection.

A modern boy bishop in Norwich – a revival of a medieval Christmas tradition. (Photo: network norfolk)

Britain’s Really Weird Christmas Customs – an Endnote

I hope you’ve enjoyed this tour of some of the quaint, but also deeply disturbing, Christmas customs of Wales and England. Though I may have been sceptical about the antiquity of particular traditions, I think we can see there are commonalities between many of them and also between them and traditions from the more remote past. Though mummers’ plays and hobby horses may not date back to pagan times, maybe they embody universal notions about midwinter in the northern hemisphere. Such notions might include the need for merriment and the idea that conventions and rules are suspended. The emphasis on death and renewal could embody both Christian beliefs about the birth, death and resurrection of Christ and older concepts about the seasons’ cycles. The traditions by which such deep notions are expressed might change, evolve, get remade, take on new influences, merge, die and be resurrected, but the notions themselves are perhaps always there, somewhere in the depths of our psyches, always waiting to be expressed.

I’d like to wish all of you who’ve read this far a very Merry Christmas and a Happy and most prosperous New Year.

(This article’s main image, showing the Welsh Christmas custom of the Mari Lwyd, is courtesy of Hearth of Brighid.)

Mummers is still a thing in eastern Canada as well, like Newfoundland . I didn’t know it’s roots were from across the sea! Ty for the fun read!

You’re very welcome, Kirsten. Interesting that the mummers found their way to Newfoundland.

The horse’s skull tradition reminds me of a Latvian pagan winter solstice tradition, where one of the masked men/women visitors is dressed as Death and everybody must dance at least one round with her (Death is female in lv) to be in good health the following year.

Thanks for your comment, Ines. I suppose if you survive a dance with Death, it shows your health is good!