The poet Thomas Chatterton – who died in August 1770 in a London garret aged just 17 – would for decades afterwards be an icon for struggling artists and misunderstood wordsmiths. He’d be an archetype for all those with leanings towards the Romantic and gothic – Blake, Byron, Keats and Shelley praised him while the Pre-Raphaelites put him in their pictures. Chatterton was widely thought to have committed suicide, after ripping up his rejected and scorned manuscripts and hurling them across his garret. How could such a youth not become a symbol of the doomed artist, of the ignored genius, of precocious talent spurned by an increasingly mechanistic, materialistic and shallow civilisation?

His life story does read like a gothic novel or Romantic poem – an epic in which art and imagination launch a promethean challenge against the gods of poverty, indifference and prejudice. Chatterton spent a lonely childhood poking around his local – and extravagantly gothic – church, even learning to read from the ancient parchments and medieval manuscripts he stumbled across in there. Later Chatterton struggled to hold onto his poetic muse in the face of mistreatment from sadistic schoolmasters, the beatings and humiliations of an enervating apprenticeship, and – as he tried to make it as a professional writer – a crippling lack of cash.

But what’s more famous than Chatterton’s life is his death. It’s become a cliché of artistic demise – the despairing genius ending it all in an opium-scented attic. Much of this perception is thanks to a painting – The Death of Chatterton – by the Pre-Raphaelite Henry Wallis (shown above). Completed in 1856, this image – with its clever contrasts of light and shade – has the shockingly pallid poet slumped across his bed, his frilly shirt dramatically (and perhaps a little homoerotically) falling open. The suicide’s torn-up works scatter the room; an extinguished candle smokes spookily; the bottle of arsenic which has done the deed lies discarded on the floor. The window is ajar, indicating the flight of Chatterton’s soul or muse. Out of that window, we see the dome of St Paul’s and the spires and rooftops of a city that bustles on, indifferent to the departure of genius.

The Death of Chatterton was exhibited with a quote from Christopher Marlowe’s Dr Faustus: ‘Cut is the branch that might have grown full straight, And burned is Apollo’s laurel bough’. The influential art critic John Ruskin praised the picture and crowds thronged into any gallery showing it. The man who bought The Death of Chatterton – one Augustus Egg – sold the rights to make engraved reproductions of the piece, meaning Wallis’s striking image was distributed widely.

Thomas Chatterton’s death, though, has overshadowed his equally dramatic life. Chatterton – while barely into his teens – pulled off a forgery of faux-medieval poems so elaborate and inventive that debate seethed about their authenticity for decades after his death. In his short life, Chatterton fooled patrons, fell out with well-known gothic authors, wrote scorching political diatribes, impressed radical MPs and lord mayors, penned caustic satires, seduced numerous women, and – ominously – tumbled into an open grave.

But do the circumstances of Chatterton’s death really match the assumptions people have made about it for centuries? And should his life be viewed as a flaming comet of Romantic genius streaking across a dull sky or as a complex construct of fraud, fantasy and bullshit? Or perhaps as both? Let’s head back to a strange, impoverished Bristol childhood as we start our attempts to find out.

Thomas Chatterton’s Strangely Gothic and Pseudo-Medieval Childhood

Born in November 1752, Chatterton was – like David Copperfield – a posthumous child. His father – also called Thomas Chatterton – had been the master of a local school as well as being a sub-chanter (an assistant singer) at Bristol Cathedral. Chatterton Senior was also a musician, poet, antiquarian and numismatist who had a fascination for the occult. His early death meant Thomas was born into a precarious and impoverished situation, with his mother starting a small girls’ school and taking in needlework to avoid financial calamity.

An immense gothic edifice loomed over the lives of the Chatterton family, as it had done for generations. Their modest home stood in the shadow of St Mary Redcliffe Church. Thomas’s father’s school had also stood near this building and his uncle served as the church’s sexton (the official responsible for the maintenance of the church and graveyard). The Chatterton family had long held the office of sexton on a hereditary basis and Thomas grew up enchanted by his uncle’s work.

The Bristol house in which the poet Thomas Chatterton was reputedly raised. The wall/façade on the right is the only surviving wall of his father’s schoolhouse. (Photo: William Avery)

St Mary Redcliffe has been a place of Christian worship for over 900 years though most of the current building was constructed between the 12th and 15th centuries. The grade-I-listed church is famous for its stunning gothic architecture and is said to be one of the largest parish churches in England, if not the largest. Dramatically sited on a red cliff overlooking the River Avon, the church was used by sailors as a landmark. Seafarers would pray in it before undertaking a journey and then give thanks in the church for their safe homecoming, facts which may have led to St Mary’s enormous popularity with wealthy Bristol merchants. These traders paid for the church to be lavishly enhanced in first the Decorated Gothic then Perpendicular Gothic styles. The elaborate funerary monuments of these merchants, as well as other local notables, further embellished the building.

Young Thomas loved to wander around the church, entranced by the massive gothic arched windows, by the sombre effigies of knights and merchants recumbent on their splendid tombs, by the forests of pillars, the decorated vaults, and the numerous carvings of gargoyles, grotesques and Green Men. His enthusiasm for history and culture embodied in stone didn’t at first, however, translate into an aptitude for learning. Thomas was actually thought to be mentally backward. He showed no interest in children’s games or in the books used to teach kids to read. Thomas was prone to slipping into dreamy dazes – he might sit for hours in a silent trance before bursting into tears for no reason. Considered an imbecile, he was expelled from the first school he attended.

The nave of St Mary Redcliffe, Bristol, the stunning gothic church that inspired Thomas Chatterton. (Photo: Alex Zhurakovskyi)

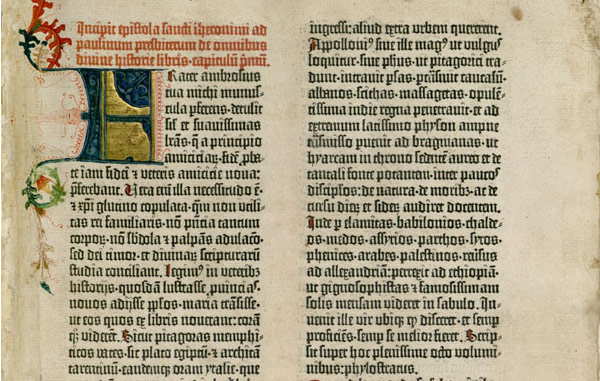

This began to change when Thomas became aware of the old manuscripts St Mary Redcliffe held. In the church’s muniment room – a space over the porch on the north side of the nave that contained chests of documents – he found dusty and forgotten parchments and deeds, some dating back as far as the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487). Fascinated, he used these ancient records as his playthings and this seemed to ignite a passion for reading. He learnt his first letters from a musical folio with illuminated capitals, one of a batch of medieval folios his father had fetched home from the church some years earlier. Despite Chatterton Senior’s antiquarian interests, he appears to have had no notion of preserving these precious documents, but had rather intended they should be used as sewing patterns or as bindings for his pupils’ books. Thomas’s mother had been about to tear up a folio for waste paper when its beautiful ornamentation captured Thomas’s gaze. According to his mother, Thomas ‘fell in love’ with the capitals so she seized on the chance to teach him the alphabet with the folio’s help. If this story is true, it indicates Thomas’s instinctive delight in medieval art as well as the meagre regard those around him had for cultural relics.

A mid-15th-century musical manuscript with an elaborate illustrated capital

After swiftly mastering his letters, Thomas learnt to read from a large bible printed in blackletter font, a gothic and archaic typeface. He haughtily informed his sister that he didn’t like reading out of small books. His choice of reading matter and his explorations of St Mary Redcliffe seem to have incited an enthusiasm for the gothic, religious and medieval as well as perhaps notions of personal grandeur. When his sister asked what design he’d like painted on a bowl he’d been given, Thomas said, ‘Paint me an angel, with wings, and a trumpet, to trumpet my name all over the world.’ This early egotism was perhaps a reaction to a growing sense his father’s death had robbed him and his family of respect and status in the local community.

By the time Thomas was six-and-a-half, his mother was realising her boy might be gifted. By the age of eight, he’d read and write all day if no one disturbed him and would devour any books he could obtain. Also at eight, Thomas was sent to Colston’s Hospital, a charitable boarding school founded by the Bristol-born merchant, Tory MP and slave trader Edward Colston (1636-1721), whose statue near Bristol Harbour was controversially torn down during a Black Lives Matter protest in June 2020. Colston had peevishly insisted that only the sons of Anglican and Tory-supporting families could attend the school and – perhaps unsurprisingly – it was a far from appropriate environment for the sensitive Thomas Chatterton. The curriculum was limited to practical subjects like reading, writing, arithmetic, commerce and law, as well as the Anglican catechism (a document expounding the basics of the Church’s doctrine). Discipline was harsh, any boys showing the slightest tendencies towards religious non-conformity were immediately expelled, and pupils had to submit to having the tops of their heads shaved so they were tonsured like monks. Chatterton’s behaviour at the school – where he spent a miserable six years – alternated between delinquency and sulkiness. The only positive aspect of his experience there was the presence of Thomas Phillips, a talented poet employed as an assistant teacher. Phillips provided encouragement to any pupils – Chatterton included – with poetic inclinations.

Pages of a blackletter Gutenburg Bible. Thomas Chatterton learnt to read from a bible printed in this gothic script.

Thomas Chatterton began to write poetry at 10. At the age of just 11, he had his first works published – some religious poems inspired by his confirmation appeared in Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal. Another Chatterton poem the same journal printed concerned an act of vandalism that had taken place at St Mary Redcliffe. A beautiful cross of unusual workmanship – which had been in the church for at least three centuries – had in 1763 provoked the rage of a puritanical churchwarden who decided it was an idolatrous monument and destroyed it. On 17th January 1764, this overly pious person found himself the subject of a clever satirical poem by the precocious Thomas, which transformed him into a laughing stock across Bristol.

Despite these fleeting successes, the youthful Thomas Chatterton was realising life was tough. In addition to being poor and fatherless and being forced to attend a brutal educational establishment, he had a growing awareness that his sensitive disposition and artistic leanings were out of place in late-18th-century Bristol. A thriving seaport and mercantile centre, this busy and money-orientated metropolis appeared to have no time for poetic fancies or the appreciation of art. Unsurprisingly, Chatterton couldn’t help contrasting this abrupt and utilitarian attitude with the gothic carvings, the beautifully scripted documents and the lovingly constructed medieval church that had so enraptured his early childhood.

Vault of the Nave of St Mary Redcliffe, Bristol, the local church of the poet Thomas Chatterton. (Photo: NotFromUtrecht)

Chatterton retreated, both physically and mentally. He commandeered a tiny attic in his mother’s house and began to build a world more palatable to his inclinations. During holidays and whenever he could escape from school, he’d lock himself in this room with his books, which he spent his little pocket money on borrowing from a circulating library. Chatterton also filled his hideaway with drawing materials and with the treasured manuscripts and ancient parchments he’d looted from the muniments room at St Mary Redcliffe. In this attic, the impoverished boy weaved an elaborate fantasy realm, a realm that took much of its inspiration from the Middle Ages. These fantasies would result in one of the most audacious literary frauds history has ever known.

The Young Thomas Chatterton Creates an Incredible Literary Fraud

In his attic, surrounded by his books and medieval parchments, mesmerised by the gothic carvings and the romanticised images of the Middle Ages swirling in his head, Chatterton began to create not only poems but in fact a poet. He dreamt up a medieval genius, a character so powerful he’d overlap with Chatterton’s own life. Like with later artists who’d sculpt potent alter egos – David Bowie, for instance – Chatterton probably had some difficulties differentiating his own personality, worldview and creativity from those of the medieval poet he’d conjured up. Chatterton named this imaginary poet Thomas Rowley and – though imaginary – Rowley would soon be very much impinging on the ‘real world’.

Perhaps this whole turn of events was triggered by a pseudo-medieval poem Chatterton wrote at the age of 11, called Elinoure and Juga. When Chatterton showed the poem to Thomas Phillips, he for some reason claimed it was by a 15th-century poet. Chatterton was astounded when Phillips believed him and the success of this deception likely encouraged him to plunge deeper into his world of fantasy.

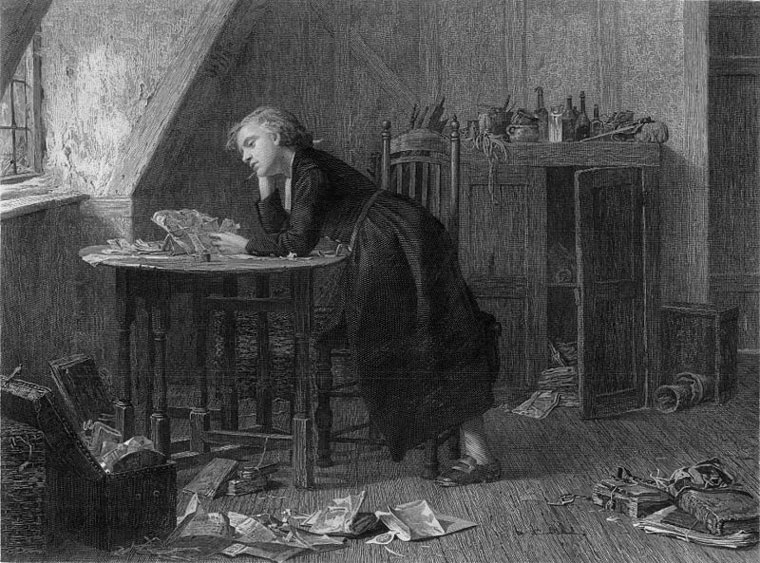

Chatterton’s Holiday Afternoon, an engraving by William Ridgway (1875) after a picture by W.B. Morris. Thomas Chatterton is shown secluded in his attic surrounded by ancient manuscripts.

Thomas Rowley – as well as being a gifted versifier – was a chronicler, priest and monk. Rowley’s poems were centred on a romanticised version of late-medieval Bristol, a town filled with citizen heroes and heroines. One of the most praiseworthy inhabitants was Rowley’s patron, William II Canynges. Unlike the mean-spirited and unimaginative bourgeoisie of Chatterton’s time, Canynges was an open-minded and munificent sponsor of literature and the arts. William II Canynges had actually been a real-life resident of Bristol. A successful merchant, he was one of the wealthiest citizens in England of his era and an occasional financier of the king. Canynges served five times as Bristol’s lord mayor and three times as an MP and dedicated a chunk of his wealth to renovating and enhancing St Mary Redcliffe. Canygnes, who died in 1474, would have been known to Chatterton as his recumbent effigy and elaborate tomb can be found in St Mary’s. His name also cropped up in the records of leases, heraldry, grants and bequests that Chatterton had purloined from the church’s muniments room.

The Rowley poems stress Bristol’s function as a strategic gateway to the West Country and the city’s admirable residents sally forth to fight against various invaders who threaten England’s liberty and independence. In Rowley’s surrealistic, dreamlike verses – and in the dramatic interludes he wrote to be performed in the grand house of his patron – his heroes and heroines speak with a passion and idealism Chatterton thought was sadly missing in the Bristol of his time. As for Canygnes, Rowley produced a poem in praise of his greatness, The Storie of William Canynge. Here we learn that Canynges – perhaps with an echo of how Chatterton saw himself – was a ‘fate-marked babe’, a child genius ‘as wise as anie of the eldermenne’. The poem then outlines a life filled with achievements, accolades and generous acts. After his wife’s death – in brave defiance of the king’s insistence he remarry – Canynges makes the noble choice to enter the Church, abandoning his worldly wealth and status and the attractions of the ‘second dames’ to become a ‘preeste for lyfe’.

The tomb of William Canynges in St Mary Redcliffe, Bristol. It supports the effigies of Canynges and his wife Joan. (Photo: Lobsterthermidor)

But if Chatterton wanted to pass off his own poems as those of a medieval writer, he had to employ language that sounded convincing. He strove to create a jargon of the Middle Ages, by scrutinising books from the circulating library as well as those he obtained by ingratiating himself with Bristol’s booksellers. He appears to have drawn much from the Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum, compiled by the philologist John Kersey and published in 1708. Other elements in his fabrication were likely taken from the works of the poet and antiquarian John Weever (1576-1632) and the writings of the antiquarian and herald John William Dugdale (1605-1686), who did a great deal to establish medieval history as a subject of serious study. Other sources appear to have been the antiquarian, genealogist and historian Arthur Collins (1682-1760) – best-known for his Peerage of England – and Thomas Speight’s editions of the great medieval poet Geoffrey Chaucer (1340s-1400). Chatterton would have studied the poetry of Edmund Spenser (1552-1599) and Shakespeare’s sonnets and plays and likely had access to Elizabeth Cooper’s The Muses Library, a whopping 400-page tome containing the works of older English poets like Edward the Confessor (1003-1066) and the Earl of Surrey (1517-47).

Chatterton probably also plundered Thomas Percy’s three-volume Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765), which included Percy’s highly useful Essay on the Ancient Minstrels, a work contrasting medieval with modern ballads. Another source seems to have been Ossian – a collection of ‘ancient Scottish epics’ the poet James MacPherson claimed to have transcribed either from accounts passed down orally or from old Gaelic manuscripts he’d discovered. These epics – the publication of which began in 1760 – were both massively popular and massively controversial, with Dr Johnson, among others, denouncing them as a fraud created by MacPherson himself. Out of these diverse, centuries-spanning sources – no doubt augmented by his finds in the muniment room – Chatterton cobbled together his fake medieval argot. A sample of Chatterton’s pseudo-medieval language – from The Storie of William Canynge – is below. This passage depicts – if I’ve understood it right – a poet reclining by the banks of a stream, musing on Bristol’s River Avon:

Anent a brooklette as I laie reclynd,

Listeynge to heare the water glyde alonge,

Myndeynge how thorowe the grene mees yt twynd,

Awhilst the cavys respons’d yts mottring songe,

At dystaunt rysyng Avonne to he sped,

Amenged wyth rysyng hylles dyd shewe yts head;

Engarlanded wyth crownes of osyer weedes

And wraytes of alders of a bercie scent,

And stickeynge out wyth clowde agested reedes,

The hoarie Avonne show’d dyre semblamente.

We might ask why Chatterton spent so much effort and time coming up with this incredible imaginary world, as well as the incredible imaginary language he used to describe it. It was partly, of course, a way of escaping from the depressing reality of his everyday existence. The psychoanalyst Louise J. Kaplan, however, also felt it had to do with Chatterton being fatherless. To compensate for this misfortune, Chatterton tried to ‘reconstitute the lost father in fantasy’ by developing an idealised image of the father-like, wealthy patron William Canynges. Kaplan also argued that Chatterton’s masculine identity had been challenged by the fact he’d been raised by two women, his mother Mary and sister Sarah. Chatterton, therefore, took upon himself a kind of ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’ narrative, in which a poor boy pursues a miraculous method of rescuing his household from poverty. Rather than using magic beans, Chatterton aimed to do this via his startling imagination and literary talents.

But to achieve his dreams Chatterton felt he’d need a patron – and finding one as wonderful as William Canynges wouldn’t be easy for a fatherless boy without connections in the materially minded Bristol of the late-1700s. Chatterton, nevertheless, was going to try.

A second effigy of William II Canynges in St Mary Redcliffe. This one was moved from the Collegiate Church of Westbury-on-Trym – where Canynges served as a canon – after the Dissolution of the Monasteries. (Photo: Lobsterthermidor)

Thomas Chatterton Tricks Patrons and Suffers a Stultifying Apprenticeship

When he was almost 15, Thomas Chatterton finally escaped the dire surroundings of Colston’s Hospital, beginning an apprenticeship in July 1767. He was to learn the duties of a legal clerk in the office of the Bristol attorney John Lambert. Chatterton wouldn’t prove a much better apprentice than he had pupil, showing little interest in his work and maintaining his sullen and insolent disposition. As for Lambert, he was enraged to find out that Chatterton wrote poetry and did all he could to stop his strange apprentice pursuing his muse. Lambert would search Chatterton’s desk and if he found any scraps of verse, would tear them up and give Chatterton a sound beating. What made this situation particularly dismal was that Chatterton, like most apprentices of his time, lived in his master’s house, meaning that – as he had at school – he could only retreat to his beloved attic during the holidays. On the positive side, Lambert was often away on business so Chatterton was left alone for long periods, which he could dedicate to his writing. Chatterton also seems to have fallen in with a crowd of young men with similar interests, a fact which no doubt spurred him on towards his goal. The interests of this group, however, also appear to have included heavy drinking and chasing girls.

In September 1768, when Chatterton was in his apprenticeship’s second year, a new bridge over the River Avon opened in Bristol, replacing a picturesque structure built in the reign of Henry II (1154-89). This event inspired Chatterton to send an article – under the penname Dunelmus Bristolienis – to Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal. Chatterton’s piece was centred around ‘a description of the mayor’s first passing over the old bridge’ and Chatterton – or Dunelmus – claimed its content derived from a 15th-century manuscript he’d unearthed. Like his Rowley writings, Chatterton’s article was bursting with a sense of history, civic pride and elaborate pageantry. The article attracted the attention of William Barrett, a surgeon with antiquarian interests. Barrett, who was searching out sources for a book that would be entitled History and Antiquities of the City of Bristol, got in touch with Chatterton.

Chatterton had soon sold Barrett the ‘manuscript’ on which he’d based his article and went on to sell him a number of Rowley works, which masqueraded under such titles as the Bristowe Tragedie or the Dethe of Syr Charles Bawdin (a ballad mourning the death of a Lancastrian knight); Ælla, a Tragycal Enterlude; and the ‘dramatic fragment’ Godwyn. Chatterton also offloaded onto Barrett the works The Tournament; Battle of Hastings; The Parliament of Sprites; and Ballade of Charitie; along with numerous short pieces. In addition, he managed to palm off onto the surgeon Rowley’s Memoirs and the History of Bristol, a document supposedly written by an 11th-century Prior of Durham that Rowley had ‘merely’ revised and corrected. The youthful poet claimed his father had found these manuscripts in a chest in St Mary’s muniments room and that he’d solely performed the service of transcribing the ancient documents to save them from oblivion. The credulous Barrett included these works in his book though it wouldn’t be published until 20 years after Chatterton’s death. Although History and Antiquities of the City of Bristol would be deemed a colossal failure, later judgement has been kind to Chatterton’s efforts, with many viewing them as powerful and (perhaps ironically considering they were forgeries) curiously original writings.

Chatterton’s article about the bridge also caught the interest of two men who ran a pewter business, George Catcott and Henry Burgum. Catcott was enchanted by the Rowley myth and would seek out and pay for works reputed to be from the pen of the 15th-century poet for years after Chatterton had died. For Burgum – a self-made man who’d risen from humble origins – Chatterton devised a fictitious aristocratic pedigree. He claimed to have unearthed a document showing the pewterer’s descent from the ‘de Bergham’ family, whose illustrious ancestry could be traced as far back as the Norman Conquest. Chatterton came up with a ‘de Bergham’ coat of arms, which he emblazoned on a piece of suitably aged parchment – probably a spare sheet from the muniments room – to which he added a written pedigree of noble lineage. Chatterton even enhanced the deception by including a Syrr Johan de Berghamme in one of the Rowley poems, The Tournament. Burgum paid Chatterton five shillings for the parchment – which Chatterton told him had lain undisturbed for centuries in St Mary Redcliffe – but it turned out Burgum wasn’t as naïve as his business partner. Growing suspicious, Burgum checked his alleged ancestry with the College of Heralds and discovered he’d been duped. Chatterton would satirise Burgum – and the five shillings he’d parted with – in a later poem.

We might wonder why Chatterton went to so much effort to pass off the products of his pen as the work of a 15th-century poet rather than claiming them as his own. One reason is that, if he had, he’d have likely been ridiculed for writing in an archaic style. There was also a certain amount of snobbery around at the time with regards to modern literature, with the idea that – especially if such literature included fantastical elements – it was the throwaway output of hack writers simply designed to entertain. Such fluff, it was thought, couldn’t be compared to the great works of the past. Another factor was that few people would have anyway believed a youth like Chatterton could have produced such pieces. Apparently, Chatterton did – on a few occasions – try to claim credit for the Rowley poems, but his assertions were just laughed at as he wasn’t considered intelligent enough to have written them.

During his apprenticeship, however, Chatterton made his first steps out of his medieval fantasy world. In this period, he also wrote modern poems, with his Resignation having attracted belated praise as especially enchanting. He developed his talent for satire too, writing endless pieces mocking the residents of Bristol, including his patrons Catcott, Burgum and Barrett, and the city’s mayor, bishop, dean and other notables. But reflecting on the course his life was taking, Chatterton realised something had to be done. Though triumphant at having gulled his three patrons, the sums he’d extracted from them were too small to make any significant difference to his circumstances. Chatterton knew he’d have to look further in his search for income, sponsorship and any sort of release from his apprenticeship’s drudgery. He’d have to look to London.

A Clash with a Gothic Writer and a Sardonic But Effective Suicide Note

In December 1768 – now aged 17 – Chatterton sent a letter to the London publisher James Dodsley. Chatterton offered Dodsley ‘copies of several ancient poems, and an interlude, perhaps the oldest dramatic piece extant, wrote by one Rowley, a priest in Bristol, who lived in the reigns of Henry VI and Edward IV.’ Though he signed the letters with the initials of his pseudonym Dunelmus Bristolienis, he requested that Dodsley’s reply should be sent ‘care of Thomas Chatterton’. He, however, appears to have received no answer. He sent another letter to Dodsley enclosing an extract from Rowley’s tragedy Ælla, but either again got no response or merely words of mild encouragement.

Still determined to find a patron of the calibre of William II Canynges, Chatterton hit on the idea of writing to Horace Walpole (1717-97). Walpole – the 4th Earl of Orford and son of the prime minister Sir Robert Walpole – was, like Chatterton, obsessed with the Middle Ages. Credited with having written the first gothic novel in English, The Castle of Otranto (1764) – a tale of ghosts, murder and family skulduggery – Walpole also spearheaded a more general gothic revival that would gather velocity in Victorian times. His palatial Twickenham mansion, Strawberry Hill, was built in a fanciful neo-gothic style and even had fireplaces modelled on tombs in Westminster Abbey.

Horace Walpole by Joshua Reynolds, painted 1756-7. For a time, the famous gothic writer corresponded with Thomas Chatterton.

Chatterton was clever in his approach to Walpole. In 1762, Walpole had published his Anecdotes of Painting in England so Chatterton made use of Walpole’s fascination for art. He devised a scenario in which William II Canynges had sent Thomas Rowley off around England to catalogue the country’s paintings. The result of Rowley’s artistic tour was The Rise of Peyncteynge yn Englande, wroten bei T. Rowleie, 1469 for Mastre Canygne. Chatterton posted Walpole this document – along with samples of Rowley’s poetry – and Walpole was intrigued. He eagerly wrote back, praising the poems as ‘wonderful for their harmony and spirit’ and stating, ‘Give me leave to ask you where Rowley’s poems are to be had. I should not be sorry to print them; or at least a specimen of them, if they have never been printed.’

Buoyed by Walpole’s response, Chatterton wasted no time in sending him more examples of Rowley’s craft. Chatterton, however, also made a serious mistake, admitting to Walpole that he was the son of a poor widow and an apprentice clerk, but that he desired a more refined occupation. He hinted that Walpole might help him achieve this and the older man’s suspicions were inflamed. Walpole showed Rowley’s works to some friends – the poets Thomas Gray and William Mason – whose opinion was that they were modern fakes, albeit ones of admirable literary quality.

Literary fraud was a sensitive topic for Walpole. Not only had he been embarrassed by declaring his belief that Ossian was genuine, but he himself had been mocked for producing a hoax. Fearing a modern novel with supernatural elements wouldn’t be taken seriously, he’d disguised his authorship of The Castle of Otranto. The first edition had been anonymously published, with its title page stating it was a translation by ‘William Marshal, Gent. From the Original Italian of Onuphirio Muralto, Canon of the Church of St Nicholas at Otranto.’ It was claimed Muralto’s manuscript had been discovered in Naples in 1529 and that this document was in turn based on a much older narrative that dated back to the era of the Crusades. William Marshal was, of course, Walpole and – though he may have been inspired to some degree by Italian legends – the ‘manuscript’ was entirely his own work. The Castle of Otranto proved immensely popular and Walpole felt obliged to add a throat-clearing explanation to the second and third editions, admitting he’d composed the story in ‘an attempt to blend two kinds of romance, the ancient and the modern.’ Following this confession, critics turned on the book, dismissing it as lightweight, ridiculous, unsavoury and even immoral.

Horace Walpole’s extravagant neo-gothic mansion Strawberry Hill. (Photo: Chiswick Chap)

With Chatterton’s deception exposed, Walpole wrote back to him coldly. He advised the young poet to remain in the attorney’s office until he ‘should have made a fortune’ and could therefore finance the artistic life he craved. Though Chatterton responded with passionate arguments against Walpole’s assertions that Rowley’s harmonies sounded too modern and that his works were unlikely to have survived since the Middle Ages, it was to no avail. The problem Chatterton now had was getting his manuscripts back as he’d sent Walpole the only copies. He had to badger Walpole three times before the more established writer got round to returning them. In his final letter to Walpole, Chatterton wrote, ‘I think myself injured, sir; and, did you not know my circumstances, you would not dare to treat me thus. I have sent twice for a copy of the M.S.: – No answer from you. An explanation or excuse for your silence would oblige.’ Chatterton also composed an insulting poem about Walpole, which seethed with class animosity. He’d claim the sole reason he didn’t send it was because ‘my sister persuaded me out of it’:

Scorn I will repay with Scorn, & Pride with Pride.

Still Walpole, still, thy Prosy Chapters write

And twaddling Letters to some fair indite,

Laud all above thee, – Fawn and Cringe to those

Who, for thy fame, were better Friends than Foes …

Had I the Gifts of Wealth and Luxury shar’d

Not poor & Mean – Walpole! thou hadst not dared

Thus to insult. But I shall live and stand

By Rowley’s side – when Thou are dead and damned.

Despite Walpole’s rebuff, Chatterton didn’t give up his literary aspirations. The London-based Town and Country Magazine published Rowley’s Elinoure and Juga in June 1769, but Chatterton was now moving towards writing more modern works under his own name and he produced few Rowley pieces in what remained of his life. Around this time, Chatterton’s mentor Thomas Phillips died, depriving him of another father-like figure. In mourning, Chatterton produced three elegies, poems some have seen as foreshadowing Keats’ style:

When golden Autumn, wreathed in riped’d corn,

From purple clusters prest the foamy wine,

Thy genius did his sallow brows adorn,

And made the beauties of the season thine.

Pale rugged Winter bending o’er his tread,

His grizzled hair bedropt with icy dew;

His eyes, a dusky light congeal’d and dead,

His robe, a tinge of bright ethereal blue;

His train a motley’d sanguine sable cloud,

He limps along the russet dreary moor;

Whilst rising whirlwinds, blasting keen and loud,

Roll the white surges to the sounding shore.

The diversity of Chatterton’s output at this point – when he still had to labour at his clerk’s desk and dodge his master’s attempts to tear up his work – is astounding. From August to November 1769, he wrote burlesques, burlettas and satires and in December had another piece published in Town and Country Magazine called The Antiquity of Christmas Games, payment for which probably eased the family finances a little. He also produced an Elegy, Written at Stanton Drew bemoaning the fact a ‘Maria’ had rejected him. Chatterton does seem to have been becoming aware of his attractions to the female sex and to have started to take advantage of it – a tendency that would soon be causing him serious problems. With girls and women, he could be blunt. In 1770, he wrote a note to one Esther Saunders arranging to meet ‘in the morning for … we shant be seen a bout 6 a Clock. But we must wait with patient for there is a Time for all Things … There is a time for all things – Except Marriage my Dear. And so your hbl Servt. T. Chatterton, April 9th.’

Despite his deeply religious background, Chatterton was evolving into a free thinker, writing, ‘That God being incomprehensible, it is not required of us to know the mysteries of the Trinity … it matters not whether a man is a pagan, Turk, Jew or Christian if he acts according to the religion he professes … if a man lives a good moral life he is a Christian.’

A certain political radicalism had also entered Chatterton’s thought. He’d become a fan of the radical MP and journalist John Wilkes, who was a supporter of the freedom of the press, freedom of religion and of America’s desire to gain independence from the British Empire. Wilkes was also a libertine, being a member of the notorious Hellfire Club, a group of free-thinking aristocrats that staged riotous parties and blasphemous mock-religious rituals. Wilkes is thought to have been responsible for an outrageous stunt – he released a baboon dressed up with horns during one of the club’s ceremonies and some members were so startled they thought it was the Devil. For Chatterton, Wilkes likely represented the kind of libertarian, progressive patriotism he’d celebrated in his Rowley poems. He soon plunged into the conflict between the more radical party in British politics championed by Wilkes and the conservative faction headed by the Queen, the Duke of Grafton and the Earl of Bute. Chatterton wrote polemics – under a new penname, Decimus – some of which made it into radical publications, including the Middlesex Journal and the April/May 1770 issue of The Freeholder’s Magazine.

Thomas Chatterton’s political hero John Wilkes. As well as being a famous radical MP, he was known as ‘the ugliest man in England’.

These successes must have been exhilarating, but they couldn’t disguise the fact Chatterton was still a desperately poor 17-year-old trapped in an unhappy Bristol apprenticeship. Vowing he’d earn his living by his pen – and knowing that to have even the slimmest chance of doing so he’d have to move to London – he came up with another clever scheme, one that inevitably involved his writerly talents. Having just posted off a political diatribe to the Middlesex Journal, on Easter Saturday 1770 he sat down to write what he termed his Last Will and Testament, a document containing a series of sardonic bequests. Claiming he’d end his life the next evening, he directed that his ‘grammar and prosody’ should be left to his former patron Mr Burgum, his ‘humility’ to one Reverend Mr Camplin, and his ‘religion’ to Dean Barton. To his home city, he left ‘all his spirit and disinterestedness, parcels of goods unknown on its quay since the days of Canynge and Rowley’ and his ‘debts in the whole not five pounds to the payment of the charitable and generous Chamber of Bristol’.

The will, however, wasn’t completely in jest and did betray much of the angst Chatterton was suffering. A more heartfelt passage commended his friend Michael Clayfield and Chatterton stipulated his mother and sister should be placed under ‘the protection of my friends, if I have any’. When Lambert saw the testament, he seems to have either taken the threat of suicide seriously or used the will as an excuse to get rid of his troublesome charge.

Lambert terminated Chatterton’s apprenticeship and the youth was free to move to London. His friends had a whip-round so he wouldn’t be totally broke when he arrived. By April 26th, Chatterton was in the capital.

London and the Death of Thomas Chatterton

Thomas Chatterton began his life in London lodging in Shoreditch, then a disreputable district on the eastern borders of the old City. He stayed at the house of a relative, a Mr Warmsley, and had to share a room with another tenant. His roommate later remarked that Chatterton would spend much of the night writing. Indeed, Chatterton’s first weeks in London were productive. He worked on eclogues, lyrics, operas and satires, as well as firing off political polemics. These political articles appeared in radical magazines though their editors paid him little and sometimes nothing. Nevertheless, intoxicated by his first scraps of London income, he bought presents for his sister and mother, posting them off with optimistic letters describing his new life. And, in a way, things were looking hopeful. The polemics written under his Decimus persona had captured the attention of his hero John Wilkes, who ‘expressed a desire to know the author’. Chatterton had also drawn the admiration of London’s liberal Lord Mayor, William Beckford, who ‘greeted him as politely as a citizen could’.

After nine weeks in Shoreditch, he moved to the neighbourhood of Holborn. Unlike in his former lodgings, he had an attic to himself so could write without worrying about disturbing fellow tenants. This attic may have recalled his old sanctuary at his mother’s house. Perhaps inspired by such memories, he worked over a Rowley poem – the Excelente Balade of Charitie – and sent it to Town and Country Magazine. It was rejected.

The move to Holborn coincided with other problems. Chatterton’s meagre income from his political writing dried up. The government was clamping down on dissent, meaning magazines had become wary of publishing polemics in the style of Decimus. On June 21st, William Beckford died, snuffing out any hopes Chatterton had of help from him, and in July the editor of Freeholder’s Magazine was jailed. Though he had some poems published in Town and Country in June and July – which, with their otherworldliness and grand mythologising, hint at themes Blake and Coleridge would explore – Chatterton was soon struggling to scrape together enough money to eat. A neighbour, Mr Cross – a pharmacist – invited the poet to share his dinner several times, but Chatterton proudly refused.

Things weren’t helped by his landlady, the perhaps ironically named Mrs Angel, raising the rent after what appear to have been some sexual shenanigans. In a letter to his old patron Catcott, Chatterton described how ‘staggering home one night from the Jellyhouse, I made bold to advance my hand under her covered way, and found her a very very woman. She is not only an angel but an arch angel; for finding I had connection with one of her assistants, she has advanced her demands from 6s to 8s 6 per week, assured that I should rather comply than leave my Dulcinea and her soft embraces.’

Chatterton’s problems seem to have tipped him into depression. Walking with a friend through the graveyard of St Pancras Old Church, Chatterton – absorbed in thought – didn’t notice a newly dug grave and tumbled into it. His companion helped him out, joking he was happy to assist in the resurrection of genius. Chatterton told him, ‘My dear friend, I have been at war with the grave for some time now.’ St Pancras Old Churchyard has literary connections – Mary Shelley’s parents were laid to rest there as was Dr John Polidori, the writer of the first vampire novel. During his career as an architect, Thomas Hardy supervised the transfer of thousands of bodies from the graveyard to make way for a railway. Could Chatterton’s topple into the grave have been an attempt by the ancient necropolis to claim another literary occupant?

St Pancras Old Churchyard, where Thomas Chatterton fell into an open grave shortly before his death. The church has several literary connections.

Chatterton’s situation grew more desperate and he even seems to have been willing to abandon his literary dreams. He wrote to his old patron Barrett asking if he could find him a position as a surgeon on ship, but – as Chatterton had no medical experience – Barrett couldn’t help. On 24th August, Mrs Angel – perhaps repenting of her earlier behaviour – realised that Chatterton ‘had not eaten anything for two or three days’ and begged him to join her for dinner. Chatterton declined, saying he wasn’t hungry, but a local baker claimed that on the same day Chatterton had tried to beg a loaf.

On the night of August 24th, Thomas Chatterton died. He’s widely believed to have committed suicide, tearing up the last poem he’d been working on and throwing the pieces on the floor before gulping down opium followed by arsenic in water. The next day, Chatterton’s room was broken open and his body was discovered in a convulsed state. His pocketbook was found too – receipts in it showed how little the magazines had paid him: a shilling for an article, less than eightpence a song and payment withheld for work accepted but not yet published. An inquest would deem Chatterton had died of arsenic poisoning.

His tragedy was compounded by the fact that – unknown to Chatterton – an Oxford academic, one Dr Fry, had become interested in the Rowley poems. A few days after Chatterton’s death, Fry came to London with the intention of finding the boy and offering him support ‘whether discoverer or author merely’. Upon hearing the sad news, Fry purchased from Mrs Angel the scraps of paper she’d swept up from Chatterton’s attic on the morning of the 25th. The poem he’d ripped up was Rowley’s Ælla – he’d probably been trying to improve the ending of that tragic interlude. Dr Fry pieced together what he could and the fragments are now kept in Bristol Public Library and Art Gallery.

Chatterton’s death would become immortalised in Romantic lore as the despairing suicide of a precocious genius rejected by an uncaring and philistine world. The praises of later generations of poets and – especially – Wallis’s highly dramatic painting have ensured this notion of Chatterton’s end has stayed wedged in the public consciousness. Chatterton may well have committed suicide: he was desperate, depressed and had – at least half-seriously – contemplated such an act before. But several modern scholars suggest a different explanation for Chatterton’s demise – accidental overdose.

This theory asserts that Chatterton had been taking arsenic to treat venereal disease. Arsenic was, in Chatterton’s era, considered a remedy for such illnesses and the poet’s chemist neighbour, Mr Cross, stated that Chatterton had been undergoing treatment for a sexually transmitted condition (probably gonorrhoea). Chatterton may have confused his dose of arsenic or unwittingly created a lethal cocktail by mixing it with opium, a drug he was known to use.

As befitted his penniless state, Thomas Chatterton was interred in the cemetery of Holborn’s Shoe Lane Workhouse. There’s a story Chatterton’s body was secretly transported to Bristol so his uncle the sexton could bury him in the grounds of his beloved St Mary Redcliffe, but there’s no evidence to support this rumour. A memorial was, however, later erected outside the church, engraved with lines from Chatterton’s poem Will:

Reader! Judge not. If thou art a Christian, believe that he shall be judged by a

Superior power. To that power alone he is now answerable.

A Doomed Romantic? A Martyr to Art? The Peculiar Gothic Afterlife of Thomas Chatterton

As Chatterton was a little-known poet – and because those who did know of him tended to view him as merely a transcriber of Rowley – his death at first attracted little comment. A book appeared in 1777 – Poems supposed to have been written at Bristol by Thomas Rowley and others, in the Fifteenth Century – edited by Thomas Tyrwhitt, an expert on Chaucer who believed the poems genuinely medieval. The book’s second edition – published the next year – did, however, admit they were probably Chatterton’s own work. Debate, though, about the authenticity of the Rowley poems raged on into the 1800s, a fact which would no doubt have amused their true author. Most scholars would eventually view the poems as ingenious forgeries.

As Chatterton did gain a little fame, one who suffered was his old nemesis Horace Walpole. Walpole spent the last 20 years of his life battling the stain on his reputation caused by the perception that a rich privileged writer had mistreated a tragic, poverty-stricken talent. Walpole did regret his disdain of Chatterton, stating ‘I do not believe there ever existed so masterly a genius.’

The Romantic Poets, however, would seize on Chatterton as a paragon of the doomed, tormented yet brilliant artist. They admired his radical politics, his dogged commitment to his vision and his martyrdom to his muse. Shelley commemorated Chatterton in Adonis, Wordsworth paid him homage in Resolution and Independence, and Coleridge praised him in Monody on the Death of Chatterton. For Wordsworth, Chatterton was ‘the marvellous boy, the sleepless soul that perished in his pride’; for Shelley, he was an inheritor ‘of unfulfilled renown’ scorned by an ungrateful public who ‘hooted him from the stage of life’. Byron contrasted him favourably with Wordsworth and Burns while Keats dedicated his Endymion – beginning with the line ‘A thing of beauty is a joy forever’ – to ‘the memory of Thomas Chatterton’. Keats felt Chatterton was ‘the purest writer in the English language … tis genuine English idiom in English words’ and William Blake proclaimed, ‘I believe both Macpherson and Chatterton that what they say is ancient, is so.’

Chatterton’s posthumous influence was by no means confined to England. The early French Romantic Alfred de Vigny came up with a play – Chatterton – in which the disparaging words of Lord Mayor William Beckford trigger the young man’s suicide. A darker side of Chatterton’s foreshadowing of the Romantic movement could possibly be seen in the early deaths of several of its leading members, but the ages at which the later poets passed on – Keats at 25, Shelley at 29, Byron at 36 – make them seem positively mature compared to Chatterton.

When the Pre-Raphaelites got hold of the Chatterton myth, his immortalisation as a dark-fated genius was complete. Henry Wallis produced his famous picture of Chatterton’s suicide, getting the young novelist and poet George Meredith to pose in the chamber of a lawyer friend in Gray’s Inn, a room whose view of the London skyline was likely similar to the one from Chatterton’s attic. The Pre-Raphaelite painter and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti was a Chatterton fan, helping prepare an edition of his poems and declaiming, ‘Not to know Chatterton is to be ignorant of the true day-spring of modern Romantic poetry.’ Later writers also found themselves influenced by the weird aura of Chatterton’s work, life and death. Oscar Wilde would campaign unsuccessfully to have a plaque to him put up at Colston’s School.

Thomas Chatterton has left a strange legacy of genius and deception, of tragedy, triumphant fraud and astonishingly precocious achievement. His life – and maybe even more so his death – for a long time shaped perceptions of what it meant to be a poet, a writer, an artist, perceptions that have proved so strong that – even in our cynical age – we have not completely eluded their shadow.

The Death of Chatterton and the surrounding auras of the genius artiste high on opiates, alcohol, sex and delusional atmospherics resonate into 2022 and no doubt beyond regardless of the ongoing infinitive of NFTs for Artists and the need for ‘artists have to live like everybody else’ (Billy Apple Exhibit title) ie; rent; mortgage; food; clothes; children; partnering; the ubiquitous car/s and more….’the more things change the more they stay the same Ho Hum!!

David, I always enjoy reading your website. You know that I am so ingrained in the subject that every nuance forces a response. Do forgive me for pointing out the following: You mention that the bible Chatterton learned to read from had gothic script, unfortunately it didn’t. It stands to reason that the bible concerned was the Chatterton family bible, which is now at Bristol Reference Library. I had the pleasure to photograph many of the pages, which I show online via my website, including the page with the handwritten details of the family, which also has the record of Chatterton’s birth. In my Chatterton madness, I have also bought copies of each of the three editions of the same bible to compare the contents – more info on the website. Best wishes and keep the faith. Richie

Many thanks for pointing that out about the Chatterton bible, Richie. So glad you’re enjoying the blog!