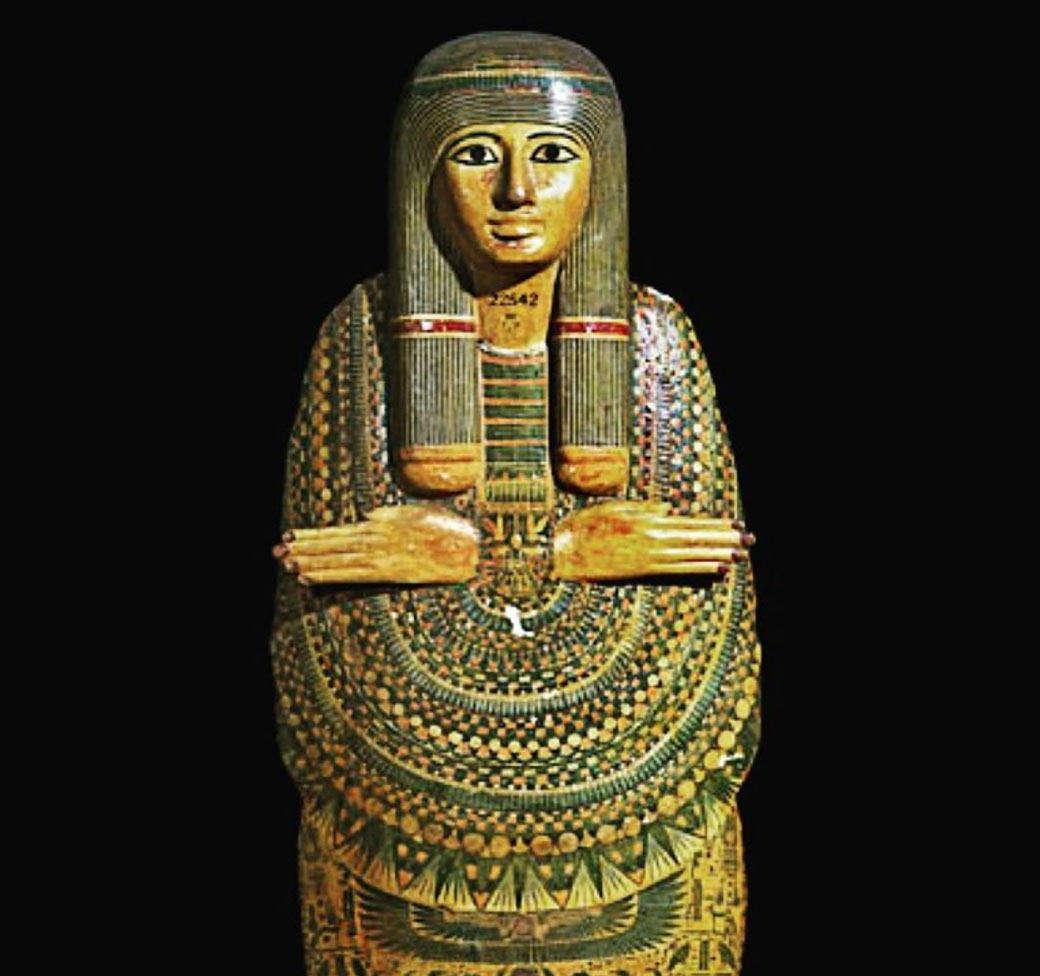

If you were to wander into the Egyptian section of London’s British Museum, you might notice – among the gloomy sarcophagi, huge stone pharaohs, bandaged mummies, sombre pillars and statues of aloof deities – a beautiful and striking coffin case.

This wooden casket – depicting the enigmatic face of a woman – is adorned with winged gods and hieroglyphs, their colours vibrant almost 3,000 years after being painted. You might be tempted to pause, to stare at the artefact. But maybe, after some time, though you wouldn’t want to yank away your gaze, you might become aware of a disturbing feeling, a mix of foreboding and fascination that grows more ominous the longer you look. Prickles could pass over your skin, your heart start to rap. Reluctantly, but thankfully, you might then haul away your eyes and drift on to other exhibits, but your weird encounter with the mummy case, and perhaps thoughts about its occupant, might linger for hours, days afterwards, cropping up in your dreams and invading quiet moments.

You wouldn’t be the first to feel this way. This object – given the identification number 22542 and currently displayed in room 62 of the museum – is at the centre of an extraordinary tangle of London folklore. Known as the ‘Unlucky Mummy’, this cursed artefact is said to have brought death, illness, injuries, bankruptcies and deep unhappiness to many who came into contact with it. It’s said to have smashed glass, spookily distorted photos, and created strange nocturnal lights and eerie footsteps in the houses it was kept in.

The Unlucky Mummy displayed in the British Museum. (Photo: Jack Shoulder)

After its donation to the British Museum, the Unlucky Mummy caused more deaths and accidents. Night-time knockings, shrieks and moans reverberated from the case. One legend asserts the Unlucky Mummy’s ghost travelled down secret passageways to haunt two London Underground Stations and was responsible for the disappearance of two women at one of those Tube stops. Some stories even maintain the mummy was on the Titanic and that it was the mummy’s curse that sank that famous ship. It’s claimed the Unlucky Mummy is the corpse of an Ancient Egyptian princess, who was also a priestess of the powerful sun god Amen-Ra. The potent magic and occult knowledge she learnt in this role allegedly made sure that all those responsible for removing her from her tomb and keeping her from her resting place were pursued and punished.

But where exactly did the Unlucky Mummy come from and how did it find its way to the British Museum? Could there be any truth in the outlandish stories attached to the artefact and – if not entirely accurate – where might these tales have originated? Read on to learn of ominous warnings from palm readers, of Victorian seances in the British Museum’s Egyptian Room, of the beginnings of lurid tabloid journalism, and of the tragic misfiring of shotguns in the marshes of the Nile.

The Ominous Legend of Amen-Ra, the British Museum’s Unlucky Mummy

A number of similar, but varying, stories tell of how the Unlucky Mummy was discovered, brought to England and ended up in the British Museum. Below is an attempt to weave these legends into a coherent narrative.

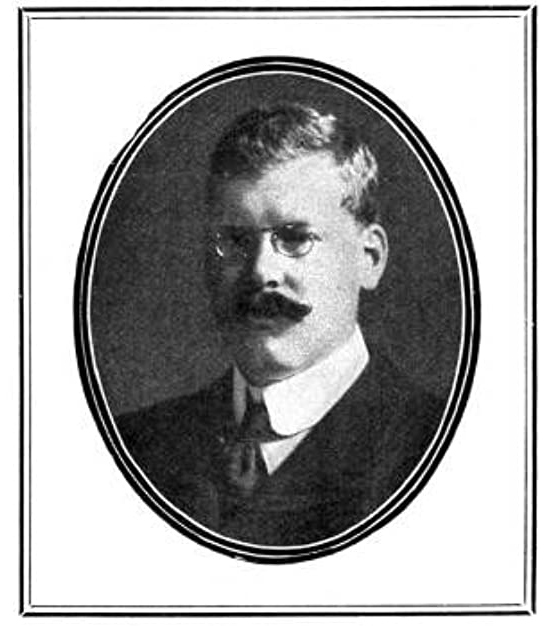

These accounts centre on one Thomas Douglas Murray (1841-1912), a wealthy Oxford graduate, author, horse breeder and amateur archaeologist. Fascinated with all things Ancient Egyptian, Murray had been in the habit of frequenting Cairo and exploring Egypt. It’s said that as a young man, Murray visited the palmist and astrologer Count Louis Hamon, otherwise known as ‘Cheiro’. The moment Cheiro took hold of his customer’s right hand, he’s reputed to have experienced foreboding and great fear, feeling that the hand would one day be separated from its owner. The palmist had visions of the hand drawing a valuable prize and of a succession of calamities following this event.

Most stories state that in the 1860s – though some place the occurrence as late as the 1880s – Murray travelled to Cairo with two companions. There they met an Arab who showed them the coffin of a freshly excavated mummy. Murray was enchanted with the well-preserved casket, dazzled by how wonderfully it was decorated in gold and enamel and by the queenly features of the young woman depicted on it. Examining the casket more closely, Murray concluded its hieroglyphs stated that the woman was a princess and high-priestess of Amen-Ra. Not only that, but the picture writing declared the princess herself was named ‘Amen-Ra’ after the god she followed. All three Englishmen yearned to purchase the splendid artefact and the Arab was eager to sell. The friends agreed that they’d draw lots and that the winner would then get to bargain for the coffin. Murray won, negotiated the relic’s price and had the case packed up and sent to England that evening.

The Unlucky Mummy, the notorious cursed exhibit of the British Museum

The Englishmen next headed up the Nile to enjoy some duck shooting. But Murray’s gun exploded, injuring his right arm. He hurried back to Cairo to seek medical attention, but his progress was hampered by weirdly powerful headwinds. What should have been a straightforward journey took 10 days and by the time Murray made it to Cairo gangrene had infected the wound. To halt the disease’s spread, his arm had to be amputated. After Murray had recovered somewhat, the three decided to return to England. Before they set off, however, they heard disturbing rumours about the man who’d discovered Murray’s mummy in Luxor. He’d either died shortly after touching its bandages or had walked off into the desert in a daze never to be seen again. Two Egyptian servants who’d handled the mummy case – and been somewhat disrespectful towards its occupant – would be dead within a year and another servant who’d cracked a joke about the mummy would meet his doom even more quickly.

On the voyage back to Britain, both Murray’s friends died and were buried at sea. On reaching his London house, and feeling far from well himself, Murray saw that the mummy’s casket had been unpacked and was waiting for him in the hallway. Rather than being struck by the beautiful craftsmanship that had so bewitched him in Cairo, Murray now sensed the artefact emanated an ancient malignity. Murray couldn’t shake the notion that an atmosphere of foreboding and evil had settled on his house. Some say that during this time Murray – who had an interest in spiritualism – was visited by the Russian occultist and founder of the Theosophy movement Madame Blavatsky (1831-91). Blavatsky immediately felt ‘an evil influence of incredible intensity’. On being asked if she could exorcise the Unlucky Mummy, Blavatsky said, ‘There is no such thing as exorcism. Evil remains evil forever. Nothing can be done about it. I implore you to get rid of this evil as soon as possible.’

Murray was, then, probably relieved when a journalist writing an article about him asked to borrow Amen-Ra’s casket. Soon after the Unlucky Mummy entered her house, her mother tumbled down some stairs and died. The journalist’s fiancé broke off their engagement, her prize dogs went mad and she became ill. She sent Amen-Ra back to Murray.

Murray, perhaps somewhat unethically, palmed the Unlucky Mummy off on a friend, a Mr Wheeler. Wheeler was deluged by misfortunes and soon died broken-hearted. Before his death, Wheeler had passed the mummy on to a married sister. Amen-Ra’s arrival in her house heralded an inevitable string of unfavourable events, but she was still fascinated enough by the casket to take it to a Baker Street studio to have it photographed. She was horrified to learn that ‘when the plate was developed, although the negative had not been touched in any way, it was seen that there looked out the face of a living Egyptian woman, whose eyes stared furiously with an expression of singular malevolence.’ Not long afterwards, the photographer died suddenly and his son suffered an accident during which he was badly cut. When a man who’d purchased one of his photos of Amen-Ra brought it into to his house, every piece of glass in his home shattered. Another photographer unwise enough to take a picture of the Unlucky Mummy smashed his thumb and his assistant – while adjusting the camera – fell and cut his face.

The next time Wheeler’s sister met Murray, she poured out this list of gruesome goings-on. Finally realising it was unfair to keep lumbering his acquaintances with Amen-Ra, Murray suggested donating the mummy to the British Museum. But this proposal didn’t lessen Amen-Ra’s malice. Murray asked a friend, an Egyptologist, to organise the transfer of the mummy to the museum. This man couldn’t resist arranging for the coffin to have a stopover at his house so he could study it. He soon died, with a servant confiding that his master hadn’t slept since the Unlucky Mummy had entered his home. The carrier who brought the case containing Amen-Ra to the British Museum died within a week. While transporting the Unlucky Mummy, his truck hit and trapped a pedestrian as it reversed and a worker who helped unload the artefact broke his leg.

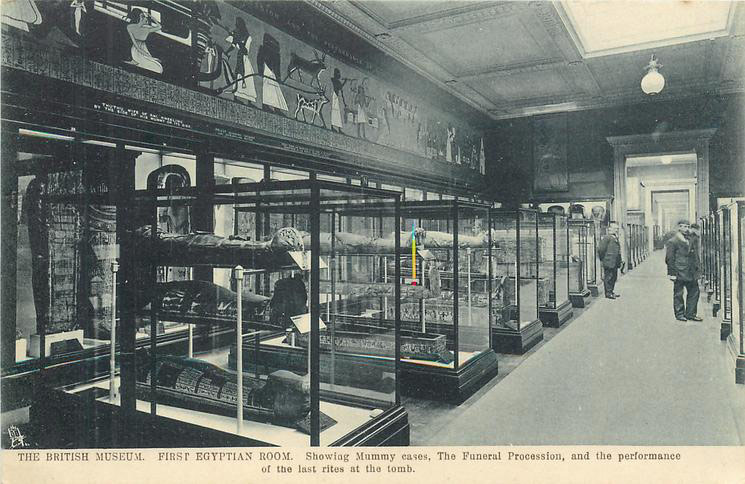

Victorian visitors examine Ancient Egyptian artefacts in the British Museum.

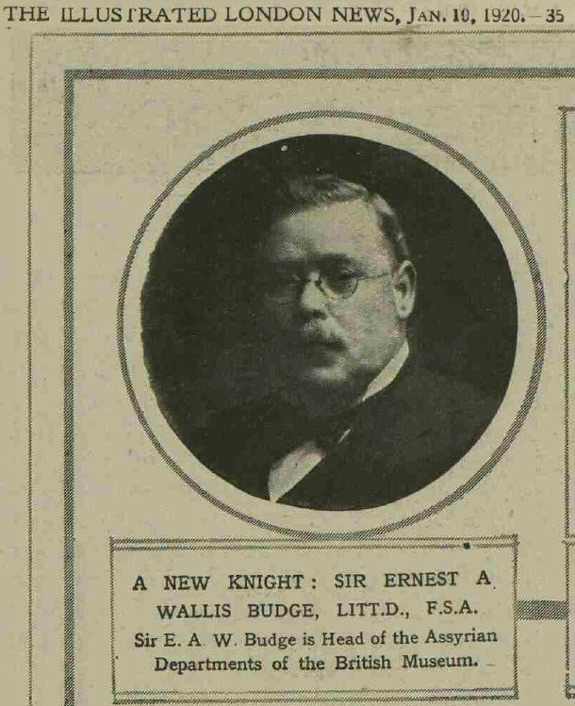

When Amen-Ra was put on display, the problems didn’t end. Nightwatchmen and cleaners reported poltergeist-like phenomena, with tappings, hammerings, moans and sobs coming from the casket. A journalist covering Amen-Ra’s story took a photo of her coffin in its glass display case. Again, the photograph revealed a woman’s face glowering with hatred. After showing the horrifying image to Sir Ernest Wallace Budge – the museum’s Keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities – the journalist went home, locked himself in a room and shot himself. Others who dared to photograph or sketch the exhibit also suffered misfortunes. A nightwatchman died as did the child of a visitor who flicked a cloth at the Unlucky Mummy. One museum employee claimed that one evening at dusk he’d seen a figure suddenly sit up in the bottom half of the casket. A being with a hideous yellow face then glided towards him in a repulsively smooth motion. Thinking the entity was going to push him down a nearby trapdoor, the man sprang forward and the apparition vanished.

Sir Earnest A. Wallis Budge, Keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities at the British Museum

According to the ghost-hunter Robert Thurston Hopkins, Budge grew increasingly worried by such reports and tried moving the Unlucky Mummy to see if this would help. Some accounts claim he sent Amen-Ra to the basement. During the Unlucky Mummy’s removal to the cellar, a man sprained his ankle and a week later the manager who’d supervised her demotion died in the museum at his desk. Most stories, however, state that Amen-Ra was simply moved from the display case she shared with other exhibits to a more prestigiously positioned case of her own. Her new home was completed with a flattering explanatory label. After this, it’s said, the disturbances became less dramatic and less frequent although for decades night cleaning staff reported ghostly appearances around the case and feelings of dread and terror emanating from it. As for Thomas Douglas Murray, the man who started all the trouble with his rash purchase of the Unlucky Mummy in Cairo, his problems didn’t cease after the British Museum accepted Amen-Ra. As the years passed, Murray’s fortune was whittled away and he died – bankrupt and in poverty – in 1912.

A Merging of Mummy Tales, Lashings of Journalistic Embellishment and a Seance in the British Museum’s Egyptian Rooms

Records indeed show the artefact that became known as the Unlucky Mummy was presented to the British Museum by a Mr A.F. Wheeler on behalf of a Mrs Warwick Hunt of Holland Park in 1890 (Wheeler’s married sister?). This, however, immediately throws doubt on the assertions Wheeler died soon after Murray had given him the mummy.

What appears to have happened is that accounts of the ‘Unlucky Mummy’ became meshed with tales of an entirely different Egyptian artefact that Murray had heard about. Murray came across the story of an Englishwoman who’d acquired an Egyptian mummy and displayed it in her drawing room. The morning after she’d installed it, she entered the room to find everything smashed. She moved the mummy to another room, only to have that room’s contents pulverised too. The mummy was exiled to the attic, but this didn’t halt the weird goings-on. That night, weighty footsteps tramped up and down the stairs, accompanied by eerie flickering lights. The following morning, all the lady’s servants quit.

This tale seems to have ignited Murray’s imagination. It’s unclear to what extent Murray really was involved with the purchase of the Unlucky Mummy and its journey to England. Some sources state he had no association with the object whatsoever until it ended up in the museum while others claim he bought Amen-Ra from an American millionaire collector of antiques, called James Carnegie. Carnegie was a patron of the famous German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann, who may have discovered the Unlucky Mummy during a dig. Whatever the truth, Murray – excited by the tale he’d heard and knowing Amen-Ra had recently been gifted to the British Museum – went to examine (or re-examine) the institution’s new artefact. He was accompanied by his friend, the famous – some would say notorious – journalist W.T. Stead.

The two men – both of whom had a deep interest in spiritualism – felt the face painted on Amen-Ra’s casket had an extremely sad look, going so far as to conclude ‘the expression on the face on the cover was that of a living soul in torment.’ This prompted Murray to contact the museum to ask if he and Stead could hold a seance in the Egyptian Section to attempt to contact the Unlucky Mummy’s spirit. According to Budge, ‘they wished to hold a seance … and to perform certain experiments with the object of removing the anguish and misery from the eyes of the coffin-lid.’

Mummies and other artefacts in the British Museum’s First Egyptian Room

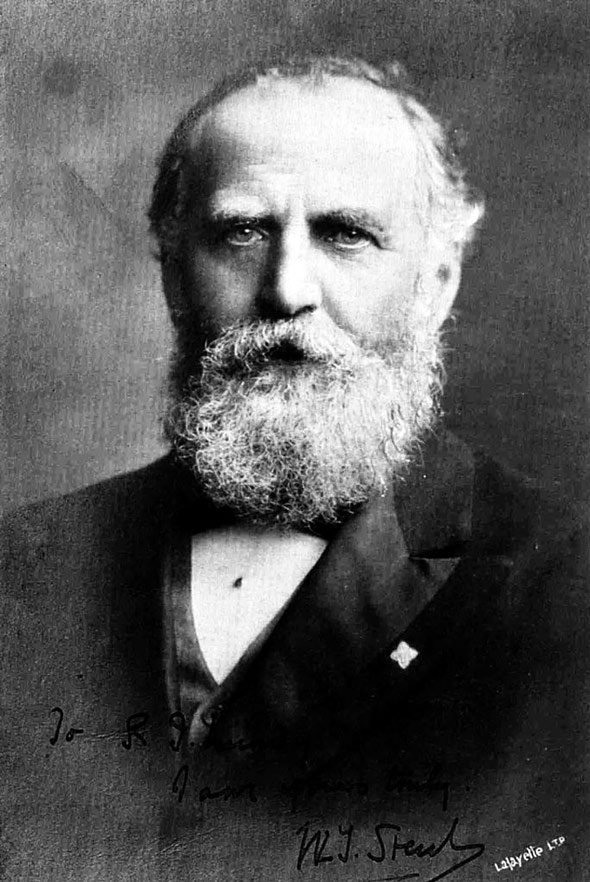

W.T. Stead (1849-1912) was one of the first investigative journalists, whose style foreshadowed much of the shock, outrage and hyperbole that would characterise 20th-century tabloid-style reporting. He was also one of the earliest media figures to recognise that journalism could sway public opinion and as editor of The Pall Mall Gazette he ran a number of controversial campaigns.

The most famous of these was centred around a series of 1885 articles entitled The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon, which dealt with child prostitution. To prove the problem of child prostitution existed, Stead set up the ‘purchase’ of one Eliza Armstrong, the 13-year-old daughter of a chimney sweep. The first instalment in the four-part series warned that the next issues of The Pall Mall Gazette were certain to sell out. Stead was proved right – copies were swapped for 20 times their normal price, 10,000 customers besieged the Gazette‘s offices and the demand was so phenomenal the Gazette even ran out of printing paper. Though considered a hero by many for exposing this trade, Stead was sent to prison for abduction – on the ‘technical grounds’ that he hadn’t first obtained ‘permission’ for his purchase from Eliza’s father. He served three months in Coldbath and Holloway jails. His journalism, nevertheless, helped pass the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885, which raised the age of consent from 13 to 16. The bill was dubbed by many the ‘Stead Act’. Stead’s campaign against child prostitution is said to have inspired George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion and even influenced Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

The journalist WT Stead in later life. Did he help invent the Unlucky Mummy myth?

Stead pioneered the use of enormous attention-grabbing headlines and inserted maps and diagrams to break up lengthy articles. He’d also incorporate eye-catching subheadings and did much to popularise the use of interviews, in which he’d sometimes mingle his own opinions with those of his subjects. His lurid descriptions of life in London’s slums pressured the government into appointing a Royal Commission, which recommended the slums should be demolished and low-cost housing put up. Stead also campaigned against brothels and gambling dens and badgered the government into the disastrous decision to send the eccentric General Gordon to protect British interests in the Sudan. As Stead’s career progressed, he became more interested in and committed to the peace movement, covering the Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907 and advocating for a ‘United States of Europe’ and ‘High Court of Justice among the Nations’ (ideals that foreshadowed the United Nations and EU). Stead was a repeated nominee for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Another, more controversial, obsession was spiritualism. Stead published a spiritualist magazine, Borderland, and maintained he was able to communicate with his deputy editor by means of telepathy and automatic writing. Stead also claimed to have acquired a spirit guide, one Julia A. Ames, an American temperance campaigner and journalist Stead met in 1890 shortly before her death. Though many Victorians lambasted spiritualism as superstitious nonsense, plenty more were fascinated by it and ouija boards and seances were fixtures of many polite drawing rooms. We had, then, the potent mix of a massively successful and influential journalist, the Victorian obsession with spiritualism and table tapping, and spooky rumours concerning Ancient Egyptian artefacts. (A craze for all things Ancient Egypt was another feature of the Victorian epoch.) This combustible concoction seems to have resulted in the birth of an explosive legend.

For any journalist at the time, the idea of a night-time seance being conducted in the British Museum’s Egyptian Rooms – with a table ringed by earnest figures surrounded by mummies and painted caskets and sombre gods – would have made excellent copy. And the unfortunate fact the museum turned down Murray and Stead’s request didn’t stop such articles being printed. The first appears to have been written by Stead himself and other excitable journalists soon picked up the story, with each likely adding in more sensationalist details in the hope of shifting newspapers. Their articles tended to merge the tormented soul of Amen-Ra’s mummy with the crockery smashing relic of the Victorian drawing room and to put this together with the idea of the aborted seance and other legends of Ancient Egyptian curses. The public lapped it up and an intriguing myth was soon in circulation.

We might wonder why Stead and Murray decided to propagate such a yarn. Both men were then in their forties, well-established and not in desperate need of funds. It seems that their profound spiritualist beliefs spurred them to make their claims about Amen-Ra’s curse. They may have hoped an outlandish story would capture the attention of those sceptical about the paranormal and lead them to an interest in spiritualist practices. If their aim was to publicise such beliefs, they succeeded as the story became widely popular, was retold frequently and resonated for years. Much of this popularity would, however, be aided by an unexpected incident, an incident that would involve W.T. Stead in the most tragic way imaginable. The myth of the Unlucky Mummy would become entwined with another story destined to assume the proportions of legend – the sinking of the Titanic.

Did the Unlucky Mummy Sink the Titanic?

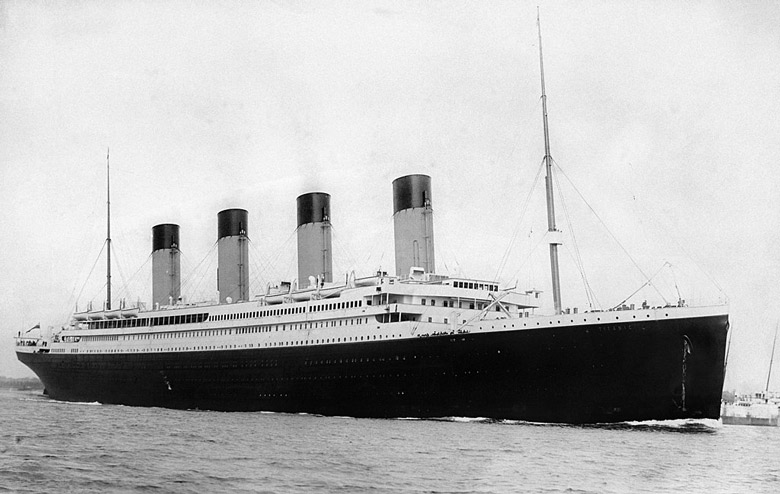

One of the most fascinating claims about the Unlucky Mummy was that it was responsible for sinking the Titanic. Apparently, the British Museum had reached the point where it could no longer tolerate the spooky goings-on around the mummy and the artefact’s curse continually injuring or picking off its staff. The decision was made to try to offload the mummy and an American collector agreed to buy Amen-Ra. Her new owner packed her up and booked a passage for himself and his new possession on a ship to the States – a ship that just happened to be the infamous Titanic. This luxurious liner, the largest ship afloat at the time, hit an iceberg then went down in the early hours of 15th April 1912 on her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York. The tragedy resulted in 1,517 deaths, mainly due to insufficient lifeboats and confused and disorganised evacuation procedures.

The Titanic setting out from Southampton – did the Unlucky Mummy’s curse sink the ship?

So was this the end of Amen-Ra? Did she sink to the bottom of the North Atlantic’s cold waters, a place from which even her powerful magic would struggle to exert its malignant influence? Apparently not, according to some versions of the story. During the chaotic scramble for the lifeboats, amidst the cries of ‘women and children first’, the collector paid a bribe to have himself and his mummy stowed in one of these lifesaving crafts. After bobbing on the night-time waves, Amen-Ra – along with the surviving passengers – was rescued by a ship named the Carpathia and completed her journey to the New York.

Inevitably, however, the Unlucky Mummy was soon causing mayhem and misery at the home of its American owner so he decided to send her back to Britain. This, for some reason, was done via Canada, aboard a liner called the Empress of Ireland. After setting out from Quebec City, the Empress collided with a Norwegian coal ship on 29th May 1914 on the St Lawrence River. The Empress sank so quickly there was only time to launch seven of her 40 lifeboats and 840 people went down with the vessel to a watery doom. Amen-Ra, perhaps unsurprisingly, avoided this fate and ended up being placed on yet another liner, the Lusitania. Off the Old Head of Kinsale, Ireland, on 7th May 1915, the Lusitania was torpedoed by a German submarine. Almost 1,200 died and this time, it’s said, Amen-Ra sank with them.

A different version of the legend states Amen-Ra did indeed go down with the Titanic and that she’ll curse anybody who dares disturb her undersea tomb. Dark mutterings of this hex were supposedly heard among the crew on a failed 1980 expedition to locate the Titanic’s wreck.

But was the Unlucky Mummy really on the Titanic and did she finish up floating down to the ocean’s bottom? Records exist for the cargo that sailed with the Titanic, a fascinating list including feathers, hatters’ fur, auto parts, rabbit hair, elastics and early refrigeration gadgets, but absolutely no mummies, cursed or otherwise. The best evidence, however, that Amen-Ra didn’t end up in the chilly Atlantic depths is the fact you can still see her today, secure and dry, in a glass display case in the Egyptian Section of the British Museum. So how did this outlandish tale of the Unlucky Mummy on the Titanic come about?

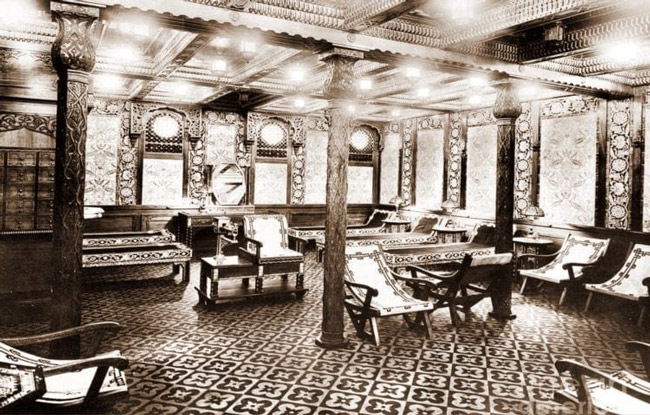

Again, it appears W.T. Stead was to blame. Stead did travel on the Titanic – he was heading to the States because President Taft had invited him to address a peace conference at New York’s Carnegie Hall. Stead couldn’t resist entertaining the other passengers with the macabre tale of the Unlucky Mummy. He’s said to have begun his narrative during an 11-course dinner party on Friday 12th April and to have drawn it out until after midnight as his listeners sat rivetted.

On the night the iceberg struck, however, Stead had retired to bed early at 10.30 pm. Witnesses observed him helping women and children into the lifeboats and in an act ‘typical of his courage, generosity and humanity’ giving his life-jacket to another passenger. He was spotted calmly reading a book in the first-class smoking room as the Titanic went down, but a survivor, Phillip Mock, recalled him later clinging to a raft with the American business magnate John Jacob Astor IV. ‘Their feet became frozen,’ Mock said, ‘and they were compelled to release their hold. Both were drowned.’ Spookily, Stead had written an article in 1886 and a story in 1892 about the calamities that could result from ships having insufficient lifeboats and hitting icebergs. Stead’s tragedy was compounded by the fact it was widely believed he was due to be awarded 1912’s Nobel Peace Prize.

Luxury on the Titanic – inside the doomed ship’s Turkish baths

The notion the Unlucky Mummy was on the Titanic appears to have come about from an article published in the New York World a few days after the ship’s sinking. The article contained an interview with a survivor – one Frederic Kimber Seward – who mentioned Stead telling his creepy story. It seems that, over time, the accounts of Stead’s presence on the Titanic and the story he narrated morphed into a belief that Amen-Ra herself had travelled on the vessel. From there, it would be just a short logical hop to assume such a famous cursed artefact had caused the ship to sink.

The Unlucky Mummy’s Killing of an Over-Inquisitive Journalist and Amen-Ra’s Haunting of a London Underground Station

Even before the Titanic catastrophe, Amen-Ra had been getting quite a reputation. As mentioned above, much of this had to do with the embellishments of journalists and one of the most famous, and tragic, to have researched the Unlucky Mummy was Bertram Fletcher Robinson. A dashing up-and-coming editor and reporter, Robinson began with the intention of debunking the far-fetched stories that had grown up around Amen-Ra. The more he investigated, however, the more he became convinced the curse was real. In 1904, an article by Robinson – A Priestess of Death – appeared on the Daily Express front page. In it, Robinson ominously wrote, ‘It is certain that the Egyptians had powers which we in the 20th century may laugh at, yet can never understand.’

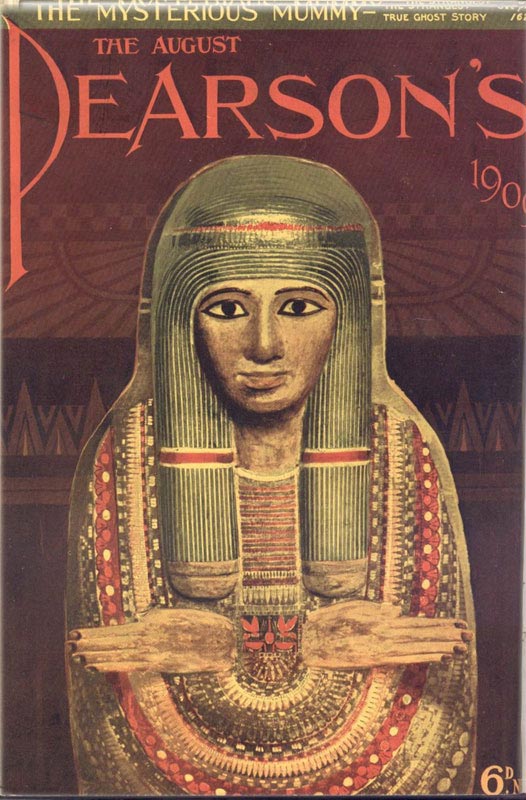

A few years later, Robinson was commissioned to write a longer article for Pearson’s Magazine, which had the same owner as the Express. As Robinson pried deeper into the secrets of Amen-Ra, his friends – aware of the disasters that had befallen those who’d dared meddle with the mummy – voiced concern. One such friend was Sherlock Holmes author Arthur Conan Doyle, who Robinson had shown around his native West Country when Doyle was researching legends of phantom black dogs for his Hound of the Baskervilles. Doyle stated, ‘I warned Mr Robinson against concerning himself with the mummy at the British Museum. He persisted …’

In January 1907 – before he could finish his article – Robinson died at the age of just 36. Much of his research did, however, end up in an article Pearson’s eventually published in August 1909. In the same piece, Doyle set forth his ideas about Robinson’s death. ‘I told him he was tempting fate by pursuing his enquiries,’ Doyle darkly stated. ‘The immediate cause of death was typhoid fever, but that is the way in which the elementals (nature spirits) guarding the mummy might act.’

Bertram Fletcher Robinson, who held editorial positions with Vanity Fair, the Daily Express and Granta. Was he killed by the Unlucky Mummy’s curse?

The Pearson’s article might be the source of – or at least be responsible for amplifying – much of the mythology around the Unlucky Mummy. The article mentions the photographer capturing Amen-Ra’s glowering face and the loss of an arm while duck shooting on the Nile. The piece, however, has the owner of the mummy dying in Cairo while we know that Murray (assuming these people were one and the same) didn’t pass away till 1912. It’s possible that the owner of Pearson’s Magazine took advantage of Robinson’s untimely death and resurrected the old mummy myth to shift copies of his publication. Throwing in quotes from the famous Arthur Conan Doyle likely did no damage to the magazine’s bottom line. Doyle could be credulous. A Freemason and committed spiritualist, he was convinced the escapologist Harry Houdini had supernatural powers, despite Houdini continually denying he possessed such attributes. Doyle was also duped into believing fairies supposedly photographed in Cottingley, Yorkshire, were real and – along with W.T. Stead – wrongly claimed two stage magicians, Julius and Agnes Zancig, had psychic abilities.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in 1893 – a believer in the curse of the British Museum’s Unlucky Mummy

An even more bizarre story about the Unlucky Mummy claims she haunted a London Underground station. British Museum Station – a now abandoned Tube stop that served the institution of the same name – was reputedly connected to the museum by a secret passageway. The ghost of Amen-Ra would progress down this tunnel at night sporting a loincloth and magnificent headdress. She’d terrify passengers and staff with horrendous, unearthly shrieks, shrieks said to have resulted from the trauma of being ripped from her tomb and brought many miles to a strange land. Her anguished howls would reverberate down corridors and along tracks, seriously disturbing all who heard them.

Was British Museum Underground Station haunted by the Unlucky Mummy’s ghost?

Thanks to the opening of Holborn Station – less than 100 metres away – in 1906, British Museum Station became less and less frequented (unless it was the ghost frightening people off). It was announced that British Museum Station would close in 1933 and – shortly before it shut – two British newspapers offered a cash reward to anyone brave enough to spend a night alone there. Nobody took up the challenge.

Some claim the legends of the haunting of British Museum Station were sparked by a film, a comedy thriller called Bulldog Jack. In this movie, a secret tunnel leads from a London Underground station to the British Museum, where it emerges from an Egyptian sarcophagus. But – as the film didn’t premier until 1935 and British Museum Station closed in 1933 – it’s more likely that the legend influenced the film rather than vice-versa. Bulldog Jack, however, helped keep alive and spread Amen-Ra’s myth, especially as the film itself would contribute in a strange way to the Unlucky Mummy’s notoriety. On the night Bulldog Jack was released, two women are said to have disappeared while walking through the tunnels of Holborn Station. Screams and moans were heard around the time they vanished and scratch marks appeared on the walls. During the following days, there were sightings of the headdress-wearing priestess. Even today, some assert, if you stand on the platform at Holborn, you can occasionally hear shrieks and wails echoing down the tracks from British Museum Station. Amen-Ra remains one of the most famous of the London Underground’s many ghosts.

Was the 1935 film Bulldog Jack partly inspired by legends of the Unlucky Mummy’s curse?

There are, though, no police records or newspaper accounts of women going missing or being murdered near Holborn Station on the night Bulldog Jack premiered and the rumours of their disappearance were likely connected to the hype around the film. The tales of British Museum Station being haunted, however, probably came from old stories of the Unlucky Mummy and the media sensationalism linked to them. Such legends were likely bolstered by the fanfare surrounding the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 and the rumours of curses in the years that followed. Again, the press played a role. Lord Carnarvon, who funded the tomb’s excavation, signed a strict and exclusive agreement with The Times that limited the rights of other papers to feature the story. When Carnarvon died shortly after the tomb’s discovery – from an infection following a mosquito bite, a similar cause of death to that which probably befell Tutankhamun – it seems the other papers took revenge, and no doubt boosted their sales, by gleefully speculating about a ‘curse’. The Daily Express quoted a mystic and novelist who claimed, ‘The most dire punishment follows any rash intruder into a sealed tomb.’

How Much Truth Was There in the Outlandish Assertions about the Unlucky Mummy and What Were the Roots of Amen-Ra’s Strange Myth?

The Unlucky Mummy has been blamed for a lot of things – illnesses, injuries, deaths, abductions, the sinking of huge ships and the terrorising of passengers and staff on the London Tube. Legend even states that Sir Ernest Wallace Budge once muttered, ‘Never print what I saw in my lifetime, but the mummy case of Princess Amen-Ra caused the War.’ Apparently, the Unlucky Mummy was presented to the German Kaiser and the string of misfortunes that followed pushed the volatile emperor towards triggering World War I.

The truth would appear less dramatic. For a start, ‘Amen-Ra’ isn’t even a mummy. The artefact said to have caused all this trouble is merely the top half of a wooden coffin, dating from around 950 to 900 BC. The mummy it would have once shielded seems to have been left behind in Egypt. As for the knockings, apparitions, injuries and deaths supposedly visited on the British Museum after accepting Amen-Ra, these persistent rumours led Budge to issue a statement in 1934 that the museum had never possessed a mummy, coffin or cover that had been involved in any paranormal occurrences. He made it clear that the museum had never sold Amen-Ra’s coffin lid, that the coffin cover had never sailed on the Titanic and that it had not left the museum since arriving there. Budge admitted the artefact had been moved to the basement, but this was simply a precaution to protect the ornate lid – as well as many other treasures – during the First World War.

As early as 1923, Budge was trying to debunk the myths around the ‘Unlucky Mummy.’ In an interview with the New York Times, Budge related how the coffin lid of Amen-Ra had become confused with the crockery smashing mummy of the suburban drawing room and how the museum authorities had turned down Stead and Murray’s request to hold a seance. Budge described some of the hysteria that had grown up around the ‘mummy’, stating that people had sent letters from as far away as New Zealand and Algiers, containing money to buy flowers to be placed at Amen-Ra’s feet. The money had been put towards the general upkeep of the museum.

But was the coffin lid – despite its romance being somewhat lessened by the fact it no longer had a mummy to enclose – really part of the burial paraphernalia of a princess and priestess called Amen-Ra? Budge thought so, agreeing with Murray’s assessment by stating the cover’s owner would have been of ‘royal blood’. Early British Museum publications describe the artefact as having belonged to ‘a priestess of Amen-Ra’. Modern experts, however, disagree. The idea the casket sheltered the remains of a princess appears to have simply arisen from the high quality of the board. Though the coffin likely protected of a person of status, there’s no evidence its occupant was royal. There’s also no proof such a person was a priestess. Budge may have wrongly reached this conclusion because of a mention of King Amenhetep I on the coffin case, a benefactor of the priesthood of Amen-Ra at Thebes, where the lid probably came from. Moreover, there’s no indication the coffin’s tenant bore the name Amen-Ra herself.

Mummies and a frieze showing funeral rites in the British Museum’s First Egyptian Room

In addition to the embellishments of journalists and misunderstandings of early curators, it seems that a cast of colourful – and far from reliable – narrators have contributed outlandish additions to the Unlucky Mummy myth. The idea about the three disrespectful Egyptian servants dying appears to have come from a book called Witchcraft and Black Magic by Montague Summers (1880-1948). Summers was a highly eccentric character who claimed to be a Catholic priest, though there’s no evidence he was ever ordained. He believed in the literal existence of vampires and werewolves and could be seen swanning around the reading room of the British Museum – in a black cloak and buckled shoes – clutching a portfolio with ‘Vampires’ written on it in big blood-red letters.

Another colourful individual linked to the Unlucky Mummy myth was the folklorist and Egyptologist Margaret Murray. Murray put forward the notion that elaborate medieval secret societies practised witchcraft as an alternative religion to Christianity, a concept that – though now largely debunked – has had a strong influence on the Neo-Pagan movement. Murray, when almost 100 years old, confessed that she liked to entertain her students by talking about ‘Amen-Ra’s evil influence’ when taking them around the British Museum. Some were so frightened, they refused to enter the room containing the coffin case. Murray also claimed she’d invented certain myths about the mummy during an interview she didn’t take seriously. The ideas about the mummy sinking the Lusitania and Empress of Ireland appear to have come from her. Murray admitted she was astonished to hear such stories earnestly repeated as fact many years later.

There’s also the palmist Cheiro, who maintained that – after his dire predictions about Thomas Douglas Murray – Murray returned to see him with his empty right sleeve fastened across the front of his coat. During this meeting, Murray apparently related his Egyptian misadventures and subsequent struggles with the Unlucky Mummy. Cheiro was another unconventional figure who claimed to have – while still in his teenage years – travelled from his Irish home to India, where he learnt occult knowledge and the secrets of palmistry from the Brahmins. He’d acquire a high degree of fame, reading the hands of influential clients such as the Prince of Wales, Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde, W.T. Stead, and the prime ministers William Gladstone and Joseph Chamberlain. Other tales about the Unlucky Mummy seem to have originated from the ghost hunter Robert Thurston Hopkins, including the story about the photojournalist shooting himself.

And what About Sir Ernest Wallace Budge? Though he felt a professional duty to present himself as a man of science, reason and scepticism, he was also fascinated by the supernatural. Budge – the British Museum’s Keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities for 30 years, a philologist and translator of the Egyptian Book of the Dead – was a member of the Ghost Club. According to Peter Underwood, author of Haunted London, ‘Budge, in private if not in public, certainly believed in Egyptian magic and the power of their dead.’ Budge died in 1934, shortly after making his statement dismissing the myths surrounding the Unlucky Mummy. Could ‘Amen-Ra’ have been avenging his belittling of her powers?

Pearson’s Magazine, featuring the curse of the Unlucky Mummy, in 1909

But we might also ask why tales of vengeful mummies and ancient curses so excited the Victorian and early 20th-century public. One reason was ‘Egyptomania’ – an enthusiasm for all things Ancient Egypt that began in Georgian times, springing from the colonial opening up of Egypt and advances in archaeology. Egyptian themes cropped up in operas and novels; tombs resembling miniature pyramids appeared in British churchyards; and Egyptian designs featured on furniture, jewellery and buildings. Egyptomania could lead to some far-fetched notions and outrageous goings-on. There were claims the Egyptians had understood the secrets of time travel – with a neo-Egyptian mausoleum in London’s Brompton Cemetery gaining a reputation as a ‘Victorian time machine’ – while the body of a Manchester heiress was even transformed by a less than honest doctor into an Egyptian-style mummy.

Yet could there be more behind this fascination for – and fear of – the legacy of Ancient Egypt? From 1798, when the French invaded Egypt under Napoleon, colonial powers – the French, the British, the Ottoman Turks and a dynasty descended from Albanian mercenaries originally employed by the Ottomans – vied for power and influence in the country. Britain launched an attack on Egypt in 1882, bombarding Alexandria for 10-and-a-half hours and causing a fire that destroyed much of the city. A successful land invasion followed and the British would remain in Egypt – in one way or another – until 1922.

Despite this victorious conquest, many in Britain felt disquiet about their country’s conduct. As would be the case in more modern times, people wondered whether a European nation should be getting involved in a Middle-Eastern country’s affairs, despite being told by their government the intervention was necessary to depose a tyrannical regime. Most of these doubters, however, didn’t express their unease openly through fear of seeming unpatriotic. Their anxieties and guilt perhaps manifested in another way – in a terror of cursed Egyptian artefacts taking revenge on Europeans who’d dared to disrespect them. An example of such an artefact is Cleopatra’s Needle, a huge obelisk that was shipped from Alexandria to London and now stands beside the Thames. The obelisk has accrued a rich folklore of hauntings, curses and occult powers.

All this combined with worries about how various types of science, and developing disciplines like history and archaeology, were upending old sacred ways of thinking. Advances in archaeology and comparative mythology – together with breakthroughs like Darwin’s laws of evolution – were making it harder to literally believe in the Bible and traditional Christianity, hence the fascination for seances and table rapping. (The growth of capitalist individualism also made it harder to accept that unique and precious individuals could one day cease to exist – thus the attempts to contact loved ones on ‘the other side’.) What better metaphor could there be for science overturning and outraging the ancient and sacred than archaeologists rifling Egyptian tombs and museum curators examining and labelling artefacts then placing them in the sterile environment of the glass case? And what better encapsulation of fears about where such sacrilege could lead than thrilling legends of age-old magical curses, legends ably amplified by a growing modern media?

In Guy Boothroyd’s 1899 novel Pharos the Egyptian, a character asks, ‘And pray by what right did your father rifle the dead man’s tomb? Perhaps you will show me his justification for carrying away the body from the country in which it had been laid to rest, and conveying it to England to be stared at in the light of curiosity.’

Such anxieties and fears have not departed even today. Visitors still report unsettling sensations when viewing the Unlucky Mummy’s coffin lid. In 2013, there was intense curiosity – and not a little unease – when an Egyptian statuette in the Manchester Museum began rotating in its case. (The rotating turned out to be caused by vibrations from passing traffic and visitors’ footsteps.) A May 2020 article in The Sun claimed that security guards in the British Museum had been witnessing strange phenomena like unexplained footsteps, glowing white orbs hovering above staircases, sightings of a ghostly female dwarf, alarms going off for no reason at midnight, and sudden plunges in temperature in the Egyptian galleries.

One guard – who’d worked at the museum for 29 years – said, ‘It was like walking into a freezer. My stomach turned over. The feel of the gallery was – you wanted to get out. I’m a great believer that, wherever you’re buried, you should stay there. A lot of the mummies there should be back in their graves.’

I love your in-depth and beautifully written articles.

Many thanks, Eneele, glad you enjoyed the tale of the British Museum’s Unlucky Mummy!

I’m obsessed with Ancient Egypt, the Victorians, and their passion for all things Ancient Egyptian, so I was delighted to discover this story. Greetings from Buenos Aires!

Glad you enjoyed it, Eneele. There are quite a few other articles on this site about the Victorians and their Egyptomania.

riveting read! the description of stead’s evening of storytelling on the titanic, followed by his helping people into lifeboats, then reading as the ship went down was absolutely gripping!

Thanks, Barbara, glad you enjoyed it.

I came in expecting a 2 minutes read about something I already knew with shallow coverage. However, as it turns out, you provided an incredible insight into Egyptomania, provided an in-dept retelling of the story from all facets and perspectives, as well as telling them in an entertaining and easy to digest style. I would love to say how very well done this piece is, and I left, after reading the piece, more knowledgeable (and also spooked). Many thanks for your great work, and I hope to read more of your great style! You have +1 fan!

Thanks, Banks, glad you enjoyed it.

Thank you so much for this beautiful article! I like the parts that explain people’s feelings towards their country’s conduct. So rational. So good.

Thank you, so glad you enjoyed the tale of the Unlucky Mummy.

I’ve been obsessed with all things Egypt since the age of 7. I often come on here to read such interesting facts about Egypt, but this one was like no other! It is written exceptionally well. I would love to visit this museum in person someday.

Thank you for such an in-depth and detailed reading experience. Greetings from India!

Hi Saranya, thanks for your comment. I’m glad you enjoyed the story of the British Museum and its unlucky mummy.