When an old house in Wellington, Somerset, was being demolished in 1878, a somewhat sinister discovery was made in the attic. The attic – inaccessible from the interior of the house – was found to contain items associated with witchcraft.

There were six brooms, an old armchair and – most mysteriously – a one-and-a-half-metre-long piece of string with chicken feathers woven into it. The workmen who found these objects assumed the chair was for witches to rest in, the brooms for them to fly on and the string to act like a ladder to help them to get across roofs.

The house already had an ominous reputation among local people as a woman rumoured to be a witch had lived and died in the building. The workmen’s finds strengthened these fears and dark whispers circulated about the house and what might have gone on in there.

These feverish speculations – especially about the ‘witch’s ladder’, as the feather-entwined string came to be known – would stretch far beyond Somerset and would entangle some of the Victorian world’s most eccentric scholars, imaginative writers and erudite folklorists.

Perhaps as a reaction to the mechanisation and urbanisation of their age, the Victorians were obsessed with all things rural, folkloric, mythic and magical, and so the unearthing of this West Country artefact was bound to fascinate, entrance, even ‘bewitch’ those who researched such things.

Read on to learn about knots enchanted with curses; about how aches, pains and even deaths could be woven into the ladder’s cords; about haunted moorland pools; about how the witch’s ladder could steal cows’ milk and frighten deer; about the bizarre rituals necessary to escape the ladder’s hexes; and about the wild theories of oddball Victorian polymaths.

Victorian Folklorists Find out about the Witch’s Ladder – and Get Extremely Excited

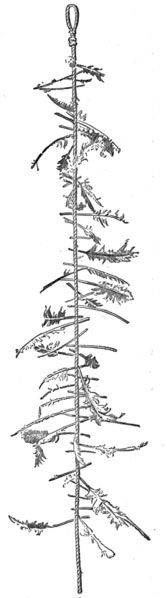

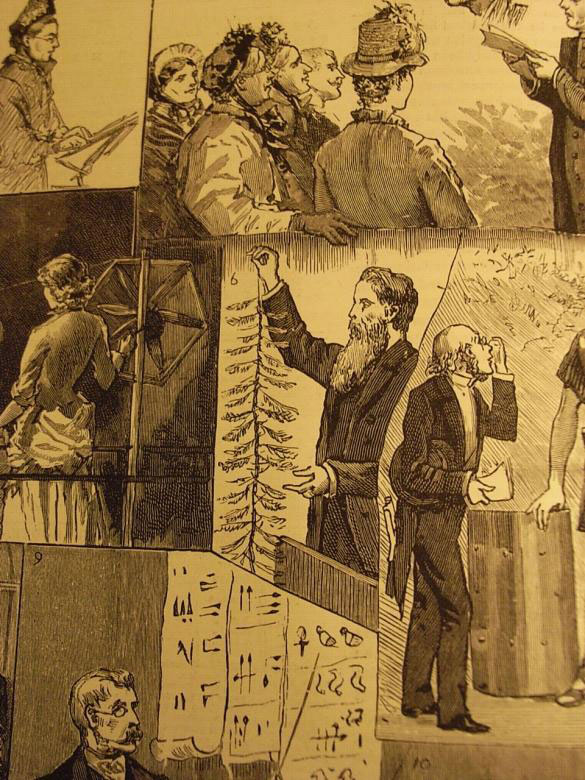

Colles’s sketch of the witch’s ladder

Although the discovery of the witch’s ladder passed into local gossip, it didn’t receive wider attention until the folklorist Dr Abraham Colles visited the Wellington area nine years later.

Upon hearing about the witch’s ladder, Colles was intrigued. He sought out the workmen who’d discovered it and interviewed them. Though Colles wasn’t able to establish why the workmen had made their assumptions about the items they’d found, he was struck by the fact they’d immediately recognised them as magical paraphernalia and had ‘at first sight designated the rope and feathers “a witch’s ladder”.’

Eager to ascertain how this ‘witch’s ladder’ had been put to magical use, Colles made more enquiries among local people. He didn’t manage to unearth much though some old ladies made vague mentions of ‘a rope with feathers’ when he asked them about witches and spells.

In 1887, Colles wrote an article – probably edited by the influential anthropologist Sir Edward Burnett Tylor – for Folk-Lore, the journal of the Folk-Lore Society. This article – complete with a sketch of the witch’s ladder – described how the artefact had been discovered as well as the little Colles had found out about its possible purposes.

Colles and Tylor’s article ignited a blaze of interest in the Victorian folklore community and triggered some fascinating suggestions about the uses of the witch’s ladder.

Italian Witches, Death Charms and Cursed Cows – Dr Colles’s Fellow Folklorists Chip in

The American folklorist, writer and humourist Charles Godfrey Leland was in Tuscany when he heard about the witch’s ladder. His curiosity kindled, Leland made some investigations and claimed that local witches used a similar item called a ‘witch’s garland’ to inflict curses.

Leland’s research about this object found its way into his book Etruscan Remains in Popular Tradition (1892). The garland, Leland wrote, was made of a cord, platted together with strands of the victim’s hair, into which black hen feathers were knotted (a slight difference to the Somerset version, which had the feathers braided in). The Tuscan witch would pluck the feathers – one-at-a-time – from a live black hen and, as she tied each feather into the cord, would utter a curse. She’d then place an image of a black cock or hen – made of cotton or a similar material – next to the garland and lay a cross of black pins upon it.

The witch would hide these items in the mattress of the person she wanted to harm. Secreted there, the garland – or ghirlanda, as it was known in Italy – caused aches, pains, illness or even death, depending on what hexes the witch had put on her victim.

To break the curse, Leland stated, the sufferer should search out the hen that had donated the feathers as well as the garland itself and fling them into running water. The victim then had to enter a church while a baptism was taking place before bathing in holy water and reciting a certain spell.

Colles’s Folk-Lore article also attracted the interest of James George Frazer, the author of the vast and hugely influential study of myth, religion and folklore The Golden Bough. Frazer suggested the witch’s ladder might have been used in magical rituals to steal milk from neighbours’ cattle, citing similar practices he’d researched in Germany and Scotland.

The Witch’s Ladder Makes Its Literary Debut

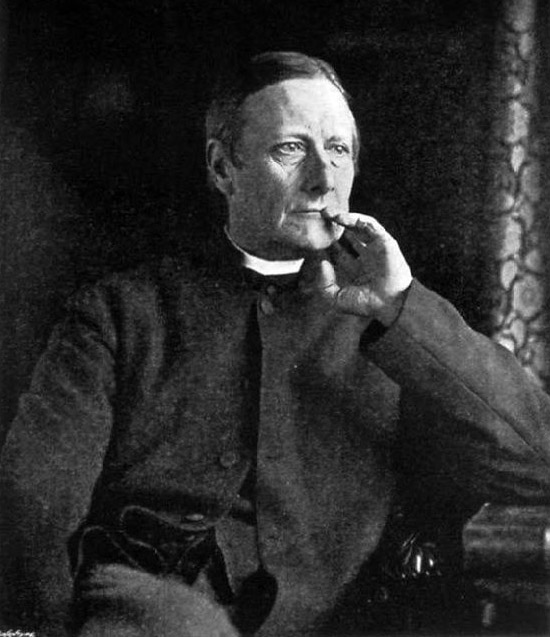

It’s hardly surprising that an odd and intriguing artefact like the witch’s ladder was soon cropping up in the literary output of excitable Victorians. The Devon vicar Sabine Baring-Gould – an energetic hymn-writer, folksong collector, antiquarian, author and eclectic scholar who churned out at least 1,240 publications – included a witch’s ladder in his 1893 novel Mrs Curgenven of Curgenven.

Baring-Gould’s witch’s ladder is made of black wool and white and brown thread, with alternate cocks’ and pheasants’ feathers woven in every two inches. The novel describes how the ladder will curse a particular character: ‘There be all kinds o’ aches and pains in they knots and they feathers … ivry ill wish ull find a way, one after the other, to the jint and bones and head and limbs o’ Lawyer Physic.’

Baring-Gould – who, many assumed, would have heard of similar items during his research in Devon and Cornwall – has his witch cast her ladder cast into Dozmary Pool, a gloomy lake high on Bodmin Moor that’s linked to Arthurian legends and said to be haunted by a demon.

Sabine Baring-Gould had a character cast a witch’s ladder into Dozmary Pool, Cornwall. (Photo: Amanda King)

The witch’s ladder skulks on the pool’s bed and – as the water gradually rots it and undoes the knots – the curses are released and rise to the top as bubbles.

Another novel, The Witch Ladder by E. Tyler (1911), features a witch’s ladder curled up under a roof, from where it works its evil magic to weaken its victim and cause their death.

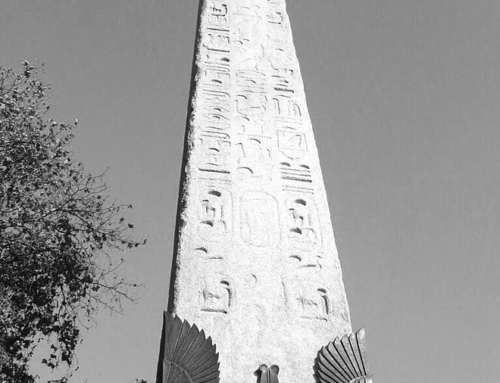

The Witch’s Ladder Is Honoured with a Place in a Prestigious Museum

The witch’s ladder discovered at the old Wellington house, now in the Pitt Rivers Museum

The Wellington witch’s ladder now hangs in the Witchcraft and Magic Case in the Pitt Rivers Museum. Part of Oxford University, this museum houses important anthropological and archaeological artefacts. Perhaps this prestigious place of display honours the impact the witch’s ladder has had on studies of magic and folklore.

The ladder was donated in 1911 by Anna Tylor, the wife of Edward Burnett Tylor, who lectured in anthropology at Oxford and was the Keeper of the University Museum. When she sent the ladder to the Pitt Rivers Museum, Mrs Tylor included a note:

‘The “witches’ ladder” came from here (Wellington). An old woman, said to be a witch, died, this was found in an attic, & sent to my Husband. It was described as made of “stag’s” (cock’s) feathers, & was thought to be used for getting away the milk from the neighbours’ cows – nothing was said about flying or climbing up. There is a novel called The Witch Ladder by E. Tyler in which the ladder is coiled up in the roof to cause some one’s death.’

Mrs Tylor’s note is more-or-less faithfully summarised on the label that accompanies the witch’s ladder in its case today:

‘Witches’ ladder made with cock’s feathers. Said to have been used for getting away the milk from neighbours’ cows and for causing people’s deaths. From an attic in the house of an old woman (a witch?) who died in Wellington.’

But is there more to the tale than this? Is this treasured artefact really a witch’s ladder or might it be something else? And – despite the confident declarations of Frazer, Leland and Baring-Gould – were Colles and Tylor always convinced about the uses of the strange object they’d stumbled across? Continue reading for controversy, doubts and dissentions among Victorian folklorists and even folk healers.

Doubts Raised about the Witch’s Ladder

On Friday 2nd September 1887, Edward Burnett Tylor presented the witch’s ladder to a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Manchester. As Tylor held up the ladder and began explaining what he thought it was, two audience members abruptly stood up and challenged him.

They claimed the object was a sewel – a stringy, scarecrow-like item made from a cord and feathers, which is hung up to discourage deer from breaking into gardens and fields. Taken aback, Tylor said he’d try to find a sewel in order to compare it to the witch’s ladder though there’s no evidence he ever did.

Disheartened by his Manchester experiences, Tylor was reluctant to display the witch’s ladder at the 2nd International Congress of Folklore in London in 1891, stating, ‘From that day to this I have never found the necessary corroboration of the statement that such a thing was really used for magic.’

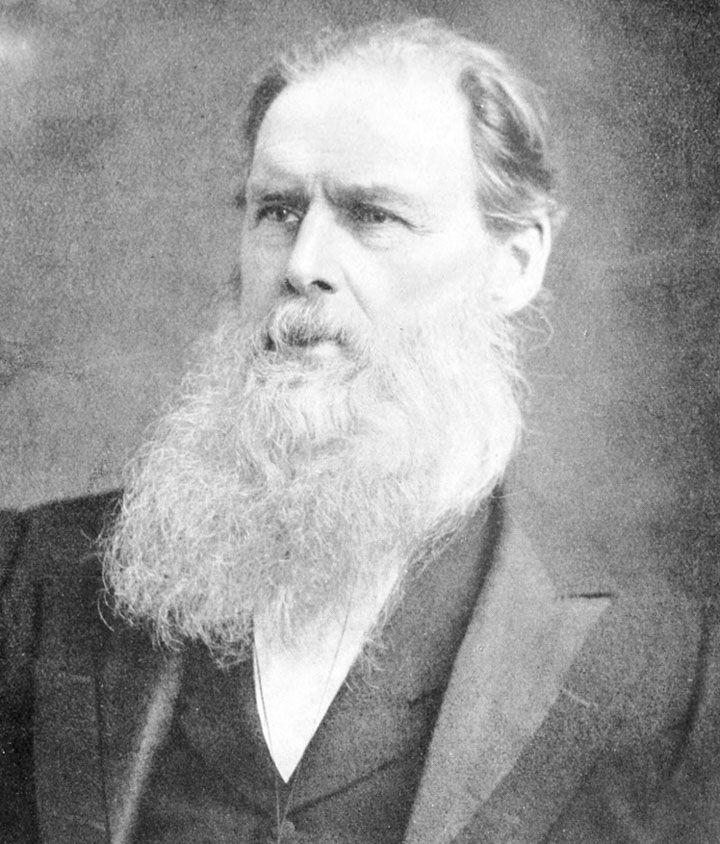

Edward Burnett Tylor – the great scholar was intrigued by the discovery of the witch’s ladder.

The witch’s ladder is, however, noted in the catalogue for the congress, suggesting that Tylor did in fact bring it, probably because attendees fascinated by the object urged him to. It’s also recorded that a Mr Gomme exhibited a photo of the ladder – perhaps this was done in case Tylor couldn’t have been persuaded to bring the artefact.

The question of the ladder’s authenticity continued to torment Tylor. After all, he had a reputation to protect. He was the first Professor of Anthropology at Oxford University and the founder of the discipline of cultural anthropology. James George Frazer was one of his followers and from 1883 Tylor served as the Keeper of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History (otherwise known as the Oxford Museum).

In 1891, Tylor mused that though ‘the popular opinion’ was that the ladder was a magical artefact, ‘unsupported opinion does not suffice, and therefore the rope had better remain until something turns up to show one way or the other whether it is a member of the family of sorcery instruments.’

Tylor was, however, still eager for any information that might determine whether the artefact was a magical tool. He hit on the idea of writing to Sabine Baring-Gould to ask what sources he’d used for the witch’s ladder in his novel. Perhaps such a learned folklorist and seasoned researcher would be able to assuage his doubts. In a letter of 1893, Baring-Gould replied, ‘I wish I could give you any thing certain about witch ladders.’

Baring-Gould, somewhat sheepishly, went on, ‘What I put into Mrs Curgenven about sinking the ladder in Dogmare (Dozmary) Pool so that, as it rotted, the ill wishes might escape was pure invention of my own. I felt they must be got out somehow & so created a fashion for liberating them.’

Sabine Baring-Gould took literary inspiration from the witch’s ladder.

To try to help Tylor, Baring-Gould made enquiries among his contacts. He spoke with Marianne Voder, a woman rumoured to be a witch. Baring-Gould told Tylor that when he asked her about the witch’s ladder, Marianne ‘professed to know nothing about such a thing and thought what you got at Wellington was nothing but a string set with feathers to frighten birds from a line of peas.’

Few other historic examples of witch’s ladders have turned up. The only other one – as far as I know – was a similar feathered rope that the Tylors donated to the Pitt Rivers Museum, also in 1911. The feathers on that one look newer and neater than on the witch’s ladder from the Wellington attic, perhaps indicating this second ladder was a recently made sewel.

But What about Charles Godfrey Leland’s Discovery of the Witch’s Garland?

But what about the customs around the witch’s garland that Charles Godfrey Leland unearthed in Italy? Don’t his findings suggest that the garland’s English cousin – the witch’s ladder – was put to similar uses?

It might be wise to take Leland’s claims with a dose of scepticism. Leland was a fascinating character who – as well as fighting in both the American Civil War and the 1848 French Revolution – undertook wide-ranging studies that encompassed folklore, Neoplatonism, Hermeticism, linguistics and ethnography. He was an important influence on the Arts and Crafts movement and researched the languages and beliefs of the European Gypsies, even serving as president of the Gypsy Lore Society.

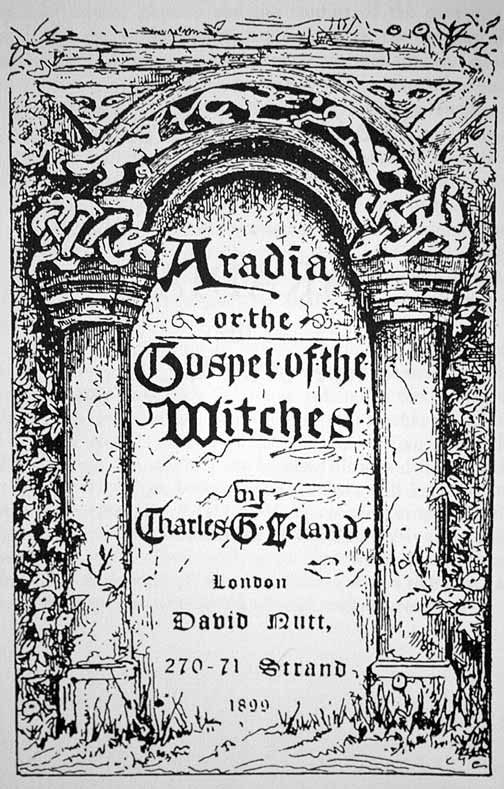

Leland is perhaps most famous for his book Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches (1899). In this text, Leland claimed to have discovered that the traditional practices of Italian witches were evidence of an age-old alternative religion, which – in opposition to Catholicism – had continued to worship the goddess Diana into modern times. Leland maintained that ‘there are entire villages in which the people are completely heathen’ and even asserted that his book incorporated a ‘lost ancient pagan scripture’. Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches has been influential in the development of Neopaganism and the Wicca religion.

Charles Godfrey Leland – a scholar and wizard?

Many of Leland’s ideas are disputed today. These include his claim that there was a cultural link between the Native American Wabanaki peoples and the Vikings and his theory that the language spoken by Irish Travellers – which he named Shelta – was the ‘fifth Celtic tongue’. In one particularly tall story, Leland asserted that not long after he was born his nurse carried him to an attic. There a ritual was conducted with a Bible, a key, candles, a knife, money and salt, with the aim of granting him a long life as a ‘scholar and wizard’. Historians have questioned his Aradia, with Elliot Rose stating that the book is merely a collection of incantations masquerading as a religion. Ronald Hutton argues that – rather than basing his work on a lost pagan scripture – Leland may have made the whole thing up.

Leland – as an intelligent and scholarly man and experienced researcher – may indeed have discovered that Italian witches knotted their curses into garlands. But – in the light of his tendencies for inaccuracies and exaggerations – his claims can’t be considered entirely reliable.

The title page of Charles Godfrey Leland’s Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches

So What Was the ‘Witch’s Ladder’?

A sceptical account of the discovery of the witch’s ladder in Wellington might run like this. The local community already associated the house with witchcraft so when workmen found broomsticks in a difficult-to-access attic, their imaginations were inflamed. Also finding a sewel – and not knowing what it was for – they decided it too must be a magical device and named it a ‘ladder’. But those brooms may have been used for nothing more astonishing than sweeping the floor and the witch’s ladder may have simply had the purpose of frightening curious deer. It’s noteworthy that the workmen also connected the utterly everyday item of the armchair to witches, claiming they sat in it to rest between flights.

When over-excitable Victorian folklorists and anthropologists heard about the find, they elaborated on the workmen’s theories and when novelists got hold of the notion of ‘the witch’s ladder’, it was forever embedded in popular culture. Thus, folklorists had themselves managed to invent a piece of folklore.

Tylor presenting the witch’s ladder to a sceptical Manchester audience

Then again, the Wellington house was linked to a witch and there may have been some truth in Leland’s assertions about Italian garlands. Placing knots in cords and strings is a well-established folkloric and magical practice. Witches used to sell fair winds knotted in pieces of string to sailors and fishermen. When the seafarers needed a good breeze, they’d untie a knot. There’s also evidence of knots being undone to cure sickness and aid childbirth and there are examples from Africa and the Arab world of sorcerers cursing people with illnesses by tying knots in strings.

Ironically, witches’ ladders may be more widespread today than they ever were in the past. Some Neopagan and Wiccan groups use them, though mainly for well-intentioned goals rather than causing harm. While chanting, the witch may knot their wishes into the ladder and objects such as bones, stones, trinkets and feathers may be bound up in it. The witch’s ladder can also, like a rosary, serve as an aid to meditation and a means of keeping count during rituals. The development of Neopaganism was influenced by writers like Gerald Gardner, Margaret Murray and Charles Godfrey Leland, all of whom were keen members of the Folk-Lore Society and all of whom would have known about the discovery of the witch’s ladder.

That worn and feathered piece of string stumbled across by Victorian workmen in that old Somerset attic has – in one way or another – had quite an impact. Unless more evidence appears, however, it’s unlikely we’ll ever know whether the ‘witch’s ladder’ really was an instrument of magic.

(This article’s main image – showing the second witch’s ladder presented by the Tylors to the Pitt Rivers Museum – is courtesy of England: The Other Within, as are the image of Tylor in Manchester and the photo of the original witch’s ladder.)

Leave A Comment